The Business of Fashion

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

SHANGHAI, China — The cool factor is notoriously hard to gain — and even harder to maintain. This couldn't be more true than in today's China. For global brands like Nike and Adidas, who have carved out an impressive market share here, China's fashionable youth have a few words of advice. You're still safe for now, they suggest, but watch out.

Li Ning is back. After years in the wilderness due to management missteps and intensifying competition in the sector, Li Ning, a champion gymnast and the founder of China's original sportswear giant of the same name, is leading an impressive and unexpected turnaround for this billion-dollar brand.

In 2018, Li Ning put on a well-received show at New York Fashion Week in February, and on June 21, the brand will present a show for its Spring/Summer 2019 collection in Paris, which is said to include a collaboration with an undisclosed high profile international designer during menswear week.

Brand consultant Liad Krispin, a former long-time marketing guru at Adidas, has been working with Li Ning since late last year. He believes now is the perfect time for a Chinese heritage brand to be asserting itself.

ADVERTISEMENT

"I think the heritage, coming from a place like China, which is not so well-known and a place that has been constantly transforming as a nation, is quite interesting. Today, it's more interesting than European or American nostalgia or heritage that we already know," says Liad, who was instrumental in premium collaborations with Yohji Yamamoto, Raf Simons and Kanye West.

“There’s a lot of Chinese heritage that will be shown in the [upcoming] collection, which is not just important for the audience abroad, but also for Chinese consumers who might know the name of the brand [and] have a certain perception of what they think the brand is. It will be quite intriguing for them as well.”

For many Chinese familiar with the brand, the glitz and glamour of foreign fashion weeks does strike a rather dissonant chord. In China, Li Ning is still more commonly associated with “Dad” trainers and pedestrian tracksuits than the streetwear-influenced sportswear behemoth with Chinese flavour that it aspires to be.

Achingly Cool Pivot

But that changed earlier this year. Fashion influencer Natasha Lau, 20, summed up the surprise of China’s fashion elite at the appearance of Li Ning last season in New York.

“It was like a bomb, everyone was like, ‘Li Ning has done a show at New York Fashion Week? And the hoodie, it was so popular. All of the stuff from Li Ning has become so fashionable, so trendy [so suddenly]. When I published pictures of me wearing the Li Ning hoodie so many people wanted to buy [the clothes],” Lau says.

According to Feng Ye, general manager of Li Ning’s e-commerce business, the New York show, which was held in conjunction with e-commerce giant Tmall, was an unequivocal commercial success among the 18 to 35-year-old Chinese audience that the brand was hoping to attract, with a staggered release of products on Li Ning’s Tmall flagship seeing one after another sell out.

Now, it's pretty easy to buy foreign brands, but if they were to disappear tomorrow, I wouldn't care.

“When the New York show came out, that marked a turning point. Before, everyone [in China] recognised the Li Ning brand, but I don’t think they really understood it or realised how good it could be. They would see the logo and not think it was so trendy or fashionable,” Feng Ye admits.

ADVERTISEMENT

To western eyes, the Li Ning logo looks suspiciously close to a “swoosh” and their original slogan “Anything is Possible” apes the “Nothing is Impossible” Adidas line, reinforcing stereotypes of China’s culture of copying.

A Chinese audience, however, sees things differently. They see the Li Ning logo (a stylised version of an L and N) as reminiscent of the character “ren” (which means “person”) and can rightfully counter that Li Ning had been using its slogan before Adidas realised the possibilities.

The ability to deeply understand the Chinese culture and point-of-view is shaping up as something of an advantage for Li Ning. After decades of assuming foreign necessarily means better quality, Chinese consumers seem to be taking a more patriotic turn. And buying domestic no longer feels like compromising to many.

Branding National Nostalgia

Some of the most popular items from the collection shown in New York were laden with Chinese cultural references, including the hoodie Natasha Lau mentions, all black with red Chinese characters spelling out “China, Li Ning” across the chest.

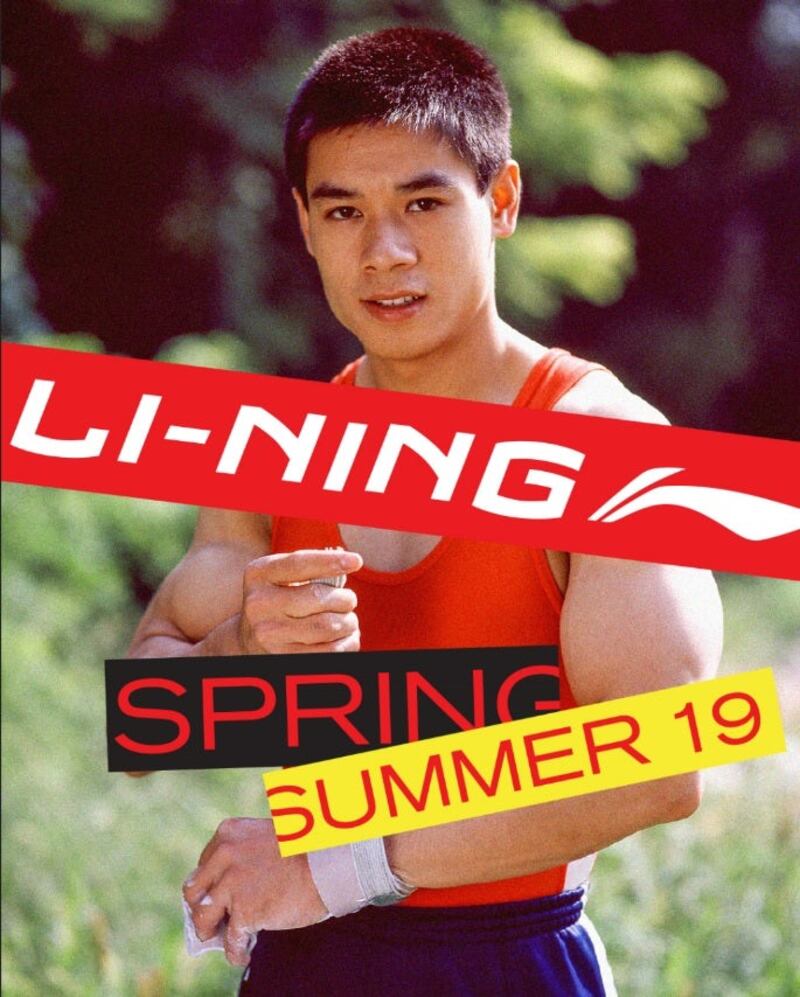

Li Ning Spring/Summer 2019 | Source: Li Ning

Also prominent were references to Li Ning himself. A photo of the athlete-turned-mogul in his heyday, effortlessly supporting his body weight, with arms parallel holding suspended rings in a move called the “iron cross,” was used on multiple items. The colour combinations of red and yellow — often worn by Chinese athletes at international competitions — harked back to his athletics days too. The Li Ning design team can conveniently look back to inspiration or cues from almost three decades of brand history, which amounts to a long heritage in China’s relatively young apparel industry.

According to Feng Ye, this sense of authenticity is particularly appealing to a proud and patriotic youth who have grown up in economic boom time and witnessed the strengthening of China’s place in the world. “In the Chinese market, it’s certainly a competitive advantage,” he says.

ADVERTISEMENT

“With Chinese culture, foreign brands might try to express culture [too] but it gives a different feeling. If [Nike] are incorporating basketball culture, hip-hop or this street culture from America, this is their culture. I’m not saying that we can’t study or try to understand or incorporate another country’s culture, but Chinese culture belongs to China alone. For Chinese people, it will have the deepest feeling,” Feng explains.

“For Chinese people, the understanding of Chinese culture is our sense of justice and righteousness, spirit, tradition. Chinese people can see this story [in Li Ning] and immediately understand all of these things. Foreigners, they can read the meaning of the translation [in the show notes] but it’s not the same.”

Gold Medal Positioning

Li Ning, the man, became a national hero in China after winning six medals at the 1984 Olympic Games in Los Angeles. His success story was symbolic of China’s early rise, and in 1990, when the champion gymnast launched China’s first real sportswear brand, it soon became the dominant player (admittedly in a market relatively free from competitors).

For China’s “post-80s” consumers, the first generation to come of age following China’s economic reforms in a land still bereft of brands, the Li Ning logo was a stamp of status.

“If you saw someone with a Li Ning bag [back then], you would think, “Oh wow, Li Ning!” It was a feeling of having something cool. Now, it’s pretty easy to buy foreign brands, but if they were to disappear tomorrow, I wouldn’t care. But Li Ning, even though I don’t buy from them much anymore, I want them to be there. I care if they exist or not,” explains Yang Zengdong, a 36-year-old teacher who grew up in Changsha, the provincial capital of Hunan Province.

There were a series of strategic mistakes made by management.

Even as international brands entered China and domestic brands proliferated, by the time of Beijing’s Summer Olympics, in 2008, when Li Ning (the man) flew dramatically around the Bird’s Nest stadium at the opening ceremony (with the help of wires) before lighting the Olympic flame, Li Ning (the company) was similarly flying.

With a valuation of $4 billion by 2010 and an ambitious 8,000-store, China-wide strategy, Li Ning abandoned its mass market, price-to-quality ratio strategy — one that is traditionally employed by domestic athletic brands in China — and attempted to compete more directly with international interlopers, Nike and Adidas, by increasing design elements along with prices (about 20 percent higher than local competitors).

But soon after, the market environment changed. “You go back to the Beijing Olympics, which cemented the iconic status of Li Ning, this was supposed to be their time in the sun, but the problem was that after the Olympics was done, people were done with sportswear as a fashion,” explains Matthew Crabbe, market research firm Mintel's Asia Pacific regional trends director.

“The fashion cycle shifted elsewhere and the domestic brands ended up with too many stores, too much inventory and problems for a number of years,” he adds.

Flipping Fortunes

In 2010, Li Ning embarked on an ambitious expansion to North America and Western Europe, opening a store and design centre in Portland — right on the doorstep of Nike’s headquarters. An American e-commerce followed and soon they were inking wholesale deals for European distribution. The attempt was short-lived, however, winding up within a few years.

Yearly losses mounted, the share price tumbled, and adding insult to injury, China’s once undisputed market leader was not only losing market share to international brands, but was overtaken by domestic rival Anta in 2012.

Li Ning Autumn/Winter 2018 show in New York | Source: Li Ning

“They were struggling before that because they were expanding aggressively, they couldn't manage their stores and products well enough, and they overspent a lot in advertising and overpriced their products, so there were a series of strategic mistakes made by management,” said Walter Woo, analyst at CMB International Capital in Hong Kong.

Founder and executive chairman Li Ning rode in on his white (pommel) horse to arrest the downward spiral in 2015, once again taking the reigns as interim CEO. The company has been on a renaissance mission ever since, retaining the increased focus on design in its products, but dropping prices once again in line with other domestic players.

Full year financial results released in March showed an 11 per cent gain in revenue in 2017, to over RMB 8.8 billion ($1.37 billion). Gross profit rose 13 per cent and operating profit for the year reached RMB 446 million ($69.5 million), representing an increase of 16 percent on the year.

“Personally, for me, [this brand] has been and still is the journey of a lifetime. I started out as an athlete and then founded my company with the dream to provide performance products to [other] Chinese athletes. We’ve come a long way since then and now are at a turning point,” founder, executive chairman and interim CEO, Li Ning said.

“We want to continue to establish Li-Ning as the strongest Chinese sports brand for both performance and lifestyle products, as well as present a clear and focused DNA and aesthetic for the brand, one that’s based on our rich heritage, our commitment to the athletes as well as our unique Chinese point of view.”

Li Ning’s bid for rejuvenation comes as China’s sportswear market evolves at an incredible speed, growing from a market value of RMB 134 billion in 2013 ($20.88 billion at current exchange) to over RMB 212 billion ($33 billion) last year, according to market research provider, Euromonitor International, which forecasts a rise to RMB 318 billion (almost $50 billion) by 2022.

This growth, in China as elsewhere, has been driven by a broader trend of athleisure and streetwear among millennials, but also by the rapid uptake of sports and fitness activities among young Chinese consumers.

China’s sportswear market leaders are undoubtedly international players Adidas and Nike, who boast a 19.8 and 16.8 per cent market share, respectively. The next biggest players are domestic brand Anta, with 8 percent of the market, and Li Ning, with 5.3 percent, according to Euromonitor data.

Online, Offline, Overseas

At the end of 2017, the total number of points of sale for Li Ning across China amounted to 6,262, a net decrease of 178 since the beginning of that year. A major part of their strategy today seems to be a more fluid approach to brick and mortar, avoiding the expansion targets of yesteryear. Adidas, by contrast, are marching onwards with store openings, announcing a target of 12,000 stores in China by 2020.

Li Ning pop-ups have become more commonplace and the company’s first “major brand experience store” opened in Shanghai in May 2017. The high-tech store stocks all the product lines offered by the company and consumers have the opportunity to try on the clothes while using sports equipment, to measure performance.

“We plan to continue our expansion of own retail both online as well as with physical stores,” Li Ning says, referring to a roll-out of many more of the big format experiential lifestyle stores later this year. “We’ve also started selling our products to top tier wholesale accounts in China which is very exciting.”

Step by step, we hope to bring Li Ning to the whole world.

“Internationally, we plan a very controlled and natural growth. We will start to offer the premium lifestyle collection to a small selection of wholesale accounts for spring/summer 2019. Step by step, we hope to bring Li Ning to the [whole] world.”

According to his e-commerce deputy Feng Ye, the Li Ning brand already has a strong and growing presence in South East Asia (largely due to its association with the sport of badminton). Russia, Africa and South America also represent growing markets.

Any move into Europe and North America, Feng says, must be predicated on a more premium positioning than the brand has traditionally occupied, not just to attract mature consumers within those markets, but also to be more appealing to their core market of Chinese consumers. “[Even] in China, the market still hasn’t reached its potential, it’s true status,” he points out.

Why then is Li Ning investing so much on big show productions and PR in New York and Paris?

Krispin explains that it is all about the boomerang marketing effect. “It feels like we should somehow capitalise on this opportunity and do it in the right way to set the stage for the brand and its expansion globally, but also its rebirth inside of China as well. This is really important to the brand [because] it’s not all about the foreign market.”

“It’s really China first and foremost.”

Related Articles:

[ Activewear Brands Limber Up in ChinaOpens in new window ]

[ With Reebok Expansion, Adidas Challenges Nike in ChinaOpens in new window ]

[ The Top 10 M&A Targets in ActivewearOpens in new window ]

With consumers tightening their belts in China, the battle between global fast fashion brands and local high street giants has intensified.

Investors are bracing for a steep slowdown in luxury sales when luxury companies report their first quarter results, reflecting lacklustre Chinese demand.

The French beauty giant’s two latest deals are part of a wider M&A push by global players to capture a larger slice of the China market, targeting buzzy high-end brands that offer products with distinctive Chinese elements.

Post-Covid spend by US tourists in Europe has surged past 2019 levels. Chinese travellers, by contrast, have largely favoured domestic and regional destinations like Hong Kong, Singapore and Japan.