The Business of Fashion

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

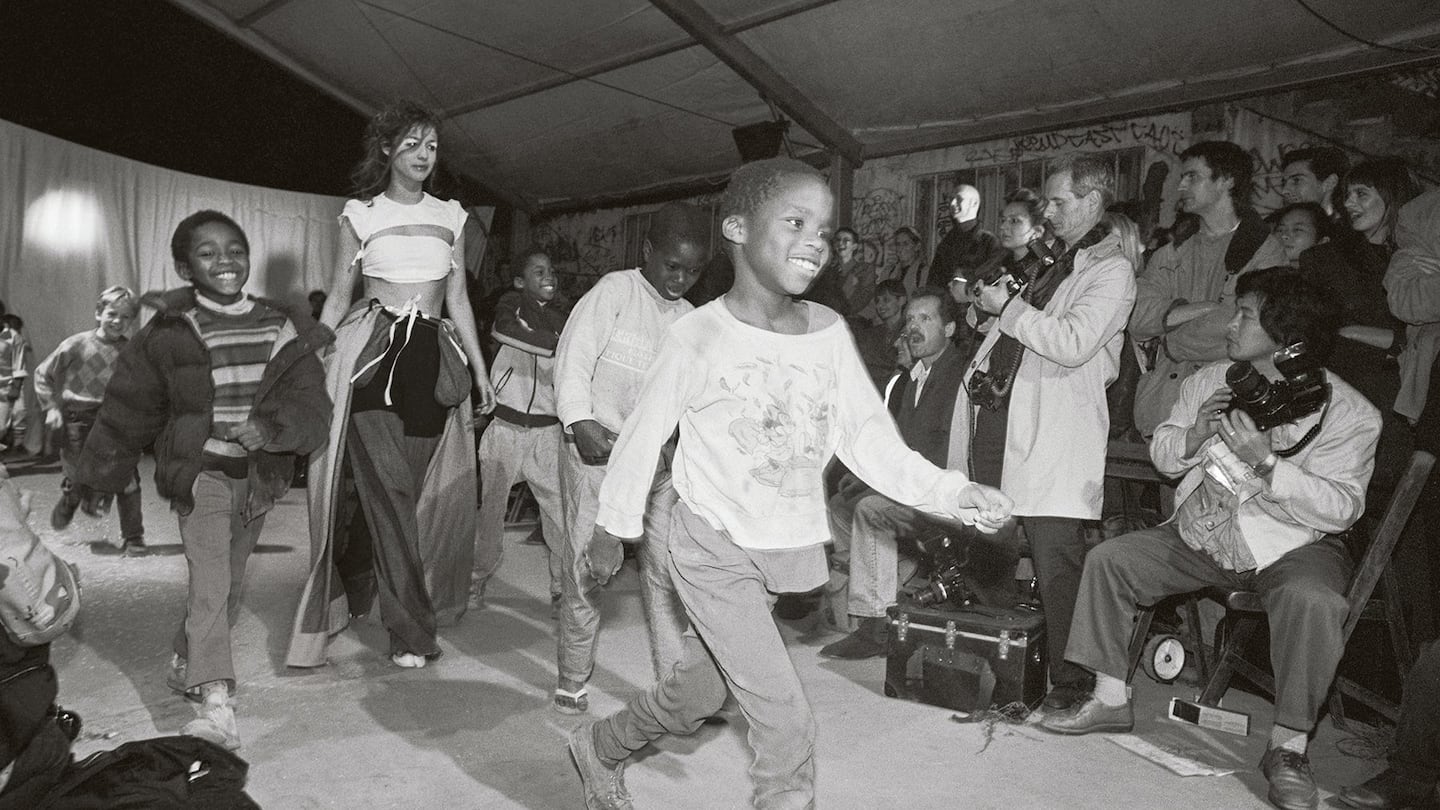

PARIS, France — In the autumn of 1989, on a derelict playground in the outskirts of Paris, Martin Margiela staged a show like nothing the fashion world had ever seen: the seating plan was first come, first served; the front row was filled with local kids; the models were stumbling; the runway was uneven. The critics loathed it. The industry loved it.

The backdrop for the collection of white and nude belted coats, wide legged trousers and carrier bag tops, all frayed and unfinished, was a wasteland replete with graffitied walls and dilapidated buildings. Richard O'Mahony of The Gentlewoman spoke to the critic Suzy Menkes, the designers Raf Simons and Jean Paul Gaultier, the professor Linda Loppa (among others) and the team that put it all together, about the show's lasting impact.

THE BUILD-UP

Pierre Rougier, press agent, Maison Martin Margiela, 1989–1992: I'd just started out on my own in 1988, and I met Martin and Jenny when I was trying to get some people to sign with me. I met Jenny first, and she asked me to meet Martin. A few days later they called and said, "We really like you but we're not going to need a press office. If you want a job, you can come and work with us." So I did, and, I mean, it was a very small set-up. I think it was Martin, Jenny, maybe Nina Nitsche [1]. Everybody was doing a little bit of everything.

ADVERTISEMENT

Jenny Meirens, co-founder, Maison Martin Margiela: Only three of us! People had been helping when needed, but it was an extremely small company.

Pierre Rougier: After the Autumn/ Winter 1989 show in March, Martin wanted a location for a magazine shoot. An actress friend of mine directed me towards this derelict area in Paris's 20th arrondissement. She'd done a shoot there and thought it might work for ours.

Jenny Meirens: We usually looked for places that people wouldn't have ordinarily used. Pierre asked me if we would be interested in this wasteland, and we thought, "Why not?"

Taken from The Gentlewoman's Spring/Summer 2016 issue

Pierre Rougier: It was a North African neighbourhood on the outskirts of Paris. Martin, Jenny and I walked around the area; then they went off together to discuss things. They would always have these types of conversations in Flemish. I didn't speak the language, so they'd go off and have their little powwow in Flemish.

Jenny Meirens: There was never anything secretive. We spoke Flemish because it was easier for us. To be honest, it was more for me — Martin wanted us to speak in French, but I thought that was ridiculous, because we're from the same country.

Pierre Rougier: They came back and said, "We want to do a show here." I thought it was crazy. They were like, "No, no, we're going to do a show here," and that was that. If Martin and Jenny wanted to do something, then it was going to happen one way or another.

Jenny Meirens: The only thing Martin and I thought might be a problem was the weather. There was no protection.

ADVERTISEMENT

Pierre Rougier: The other major issue was that it was a playground. It was pretty derelict, but an association that looked after the local kids used it. There were rules and regulations that didn't allow them to accept money for use of the area. So Jenny and Martin had the idea that we'd take the kids on a day trip to the countryside, where various activities would be laid on for them. It was important to Martin and Jenny that we were respectful of the fact that this was the kids' space and they were lending it to us for a few days.

Jenny Meirens: We wanted the children to stay around the area. Pierre suggested that we ask them to make the invitation.

Pierre Rougier: Martin hated pretty printed invitations with calligraphy. Since we were staging the show on a kids' playground, we thought it would be an idea to have the invitations drawn by kids, so it was like they were inviting you to their place. The next thing, then, was where do we find 500 kids to draw all these invitations? So we cut rectangular pieces of cardboard, gave them to the local schools, and in their art classes they were given the theme of a fashion show, and they drew their interpretations.

Jenny Meirens: The locals were very receptive and enthusiastic.

Pierre Rougier: And then we had to build the tents for backstage. That was another nightmare!

Jenny Meirens: I remember Pierre was very stressed, but Martin was always calm in preparing for a show. We were based on rue Réaumur in the 3rd then, and on one side of the studio all the outfits were being prepared, there were castings, people deciding on the make-up; and on the other side we were organising meetings with commercial clients.

Inge Grognard, make-up artist for Maison Martin Margiela, 1988–2010: I had known Martin since we were fashion-crazed teenagers growing up in Belgium and worked with him from the very beginning, so we had a well-established working pattern by this point. I was based in Antwerp. So a few weeks before a show Martin would phone and say, "OK, this is the collection," and we'd talk about the ideas behind it, the feelings, the colours. And then I'd give my input. I'd also travel to Paris because I was involved in casting the models too.

He never really told us what he wanted, just what he didn't want. He liked it when it looked as if the women could have put it together themselves.

Kristina de Coninck, model for Maison Martin Margiela, 1989–2005: Martin had seen some pictures I'd shot with the photographer Ronald Stoops and Inge for BAM magazine. Apparently, Martin said, "Who's this woman? I want her for my show." I met him in Brussels in '89, and that March I walked in his second show, which was for Autumn/Winter. The fittings for the show were such an enjoyable experience. Martin always asked the models' opinion on the clothes he selected for us — he wanted to make sure we felt good in them. For this show, he instructed us not to cut our hair.

ADVERTISEMENT

Ward Stegerhoek, hairstylist for Maison Martin Margiela, 1988–1989: Hair in the late 1980s was very proper: chignons; big, bouncy curls and waves— that sort of Claudia Schiffer look. Martin said for this show it should look like anything but a hairstyle. He never really told us what he wanted, just what he didn't want. He liked it when it looked as if the women could have put it together themselves.

Frédéric Sanchez, music director for Maison Martin Margiela, 1988–1998: This was my third show for Martin Margiela. Martin and I started work on it about two months beforehand. We'd talk about the live recordings of bands like the Velvet Underground or the Rolling Stones from the '60s— the crowd's screaming in the background, and the music's cutting in and out. We were also listening to experimental artists like Meredith Monk and Annette Peacock and obscure tracks from Factory Records. Martin was very into Bowie, too — I think the video for "Life on Mars" was a big influence on the make-up for this show. The idea was to cut all the tracks short abruptly, chop them up the way Warhol cut his movies, mess with the levels to make them sound distorted or dirty, then put it all together like a collage. It was about evoking a feeling to create something poetic. When I was told the show's location, I just thought it was very Martin. We did the first one in an old theatre, the second in a nightclub, so it was continuing this idea of using public spaces and the most lively parts of the city to present a bourgeois thing like fashion.

THE BUZZ

Roger Tredre, fashion correspondent, The Independent, 1989–1993: The Spring/Summer 1990 season was actually my first experience of fashion shows. I'd been sent to cover the collections because Sarah Mower, the fashion editor of The Independent at the time, was pregnant. Before that, I'd been working in Brussels on an English-language publication called The Bulletin, so I was very much aware of the Antwerp Six [2] fashion phenomenon. I think I did one of the first interviews with two of them, Dirk Bikkembergs and Marina Yee. There was confusion that Margiela was one of the six, which he wasn't — he'd actually graduated a few years before them and had been working for a Belgian coat manufacturer, Bartsons, then worked in Italy, and then with Jean Paul Gaultier. As the Antwerp Six's profile grew through the Golden Spindle [3] awards and following their presentation at Olympia during London Fashion Week in 1986, there was talk about this other guy who'd studied at the Royal Academy, who worked for Gaultier, and who was just as good as, if not better than the Antwerp Six.

Pierre Rougier: This was the height of Jean Paul Gaultier's fame, and M Gaultier was very supportive of Martin and very vocal about how he considered him to be the best designer of his generation. A lot of the interest from journalists and fashion editors came because of Gaultier's support.

Jean Paul Gaultier, fashion designer: He was my best assistant. When after a few years he wanted to leave and start his own collection, I could only be happy for him and wish him good luck. From Martin's first show I saw immediately that he had his own voice and his own way.

Geert Bruloot, co-owner of Louis and Coccodrillo stores, Antwerp: We were one of the first boutiques to stock Martin Margiela. I think Linda Loppa was stocking him, too. Initially, it was just a shoe line. Martin came into Coccodrillo — the shoe store my partner, Eddy Michiels, and I opened in1984 — a few months after we opened and presented his collection. Mainly shoes for women, and a lady's shoe based on a bishop shoe.

Linda Loppa, owner of Loppa boutique, Antwerp, 1978–1991; head of fashion, Royal Academy of Fine Arts, Antwerp, 1981–2006: It was like a traditional man's shoe, but made on feminine lasts. The heel looked chunky when viewed from the side but narrow from the back. The insole was higher. That's what made you taller. Already some of the classic Margiela tropes were there. They sold well.

Geert Bruloot: He stopped the line when he went to work for Gaultier. But we stayed in touch. Fashion then was bold colours, wide shoulders; everything was extravagant, very stylised — Montana, Mugler, Lacroix, Versace. Martin came along with ripped sleeves, frayed hems, clumpy shoes — we were still talking about stilettos! After seeing Martin's first show in 1988 I didn't know what to think. We watched it open-mouthed. It was like I had to erase what I thought and knew about fashion. There were production problems so the first collection was never made, and it wasn't until the second collection that we actually had clothes to sell. They didn't do very well at the beginning. But when it did start selling, it sold really well.

Fashion then was bold colours, wide shoulders; everything was extravagant. Martin came along with ripped sleeves, frayed hems, clumpy shoes — we were still talking about stilettos!

Raf Simons, fashion designer: There was so much buzz about Antwerp then. I was in my fourth year studying industrial design in Genk and had to go on work placement — I knew immediately that I wanted to do it in Antwerp. I ended up interning with Walter Van Beirendonck. It was such a fascinating period in Belgium. There were so many things going on — the Antwerp Six; Belgian New Beat [4] was taking off and bringing a new sound and dress code with it; and then there was Margiela. From the moment he did his first show in Paris, he was the one. Everyone was obsessed with Martin.

Nathalie Dufour, founder, ANDAM fashion prize: Martin Margiela was awarded the inaugural ANDAM prize in June 1989. I'd seen his first two shows in Paris and then invited him to present to our committee, which included Pierre Bergé. I remember Martin telling me that the recognition of M Bergé, and his link with Yves Saint Laurent, was very important to him — Martin loved the work of Yves Saint Laurent. He had to provide a description of his next collection, how his company was organised, a press file and such. At that time the prize money wasn't very much but it would go towards the production of the next collection and show. We weren't entirely sure it would work, but we felt something was happening and didn't want to miss it.

Pierre Rougier: There were a few influential people who got what Martin was doing and were incredibly supportive. Melka Tréanton from Elle — the grande dame of French fashion, who helped to make the careers of Mugler, Montana and Gaultier — she loved Martin. i-D and The Face in London were also supportive; Annie Flanders and Ronnie Cooke at Details in New York too. It was so different from everything else going on at that time, and people were trying to put a name to it.

Suzy Menkes, fashion editor, International Herald Tribune, 1988–2014: With half those Belgian designers it was a struggle just to find out how to spell their names! It was the end of the great explosion of extravagance of the 1980s when couture shows had become incredibly elaborate. The Belgian designers, along with the Japanese — Rei Kawakubo, Yohji Yamamoto — were very much counterculture to the big Paris houses.

THE DAY

Pierre Rougier: We finally made it to the day of the show. It was like, "Oh my God, I can't believe we're making it happen!" But, of course, we didn't have enough power, and we had to go around the neighbourhood knocking on doors asking to run cables and cords from the locals' houses so that we could plug in the hairdryers, lighting and all that. It was fucking crazy, though it didn't seem so at the time.

Inge Grognard: I had a small team of assistants. It's not like now, where there's 20 or 30. I didn't have a big make-up room, just little places where we could put one or two assistants in with two models. There were so many models! And the spaces were really dark. It was chaotic.

Jenny Meirens: Backstage really was a mess. The children had been hanging out there all day, eating the food. But it was a very cheery and relaxed atmosphere.

Ward Stegerhoek: We did try to keep them out at first. In the end, we just gave up. The backstage area was this concrete, dusty space, which was a little cold, so we had some heaters in there. And a few plastic fold-up tables and some cheap chairs. We had music like Alice Bag playing quite loud to get everyone in this punky mood. There was a little red wine too.

Inge Grognard: I'd been thinking about when you have those little accidents when doing make-up, like when you pull a sweater over your head and it smears mascara across your eyelids. We put everything on a contrasting white base. The clothes had a lot of white and plastic involved, so we mixed in some roughness with the mascara. We liked it when it wasn't totally perfect or finished.

We had to go around the neighbourhood knocking on doors asking to run cables and cords from the locals' houses so that we could plug in the hairdryers, lighting and all that.

Ward Stegerhoek: We used lots of hairspray to get the hair all matted and stiff, then started pinning it up and ended up with this rough texture.

Kristina de Coninck: Martin took one look at my wig — they used hairpieces on the models with shorter hair — and said, "It's not wild enough." So he took the hairpiece and ran it along the dusty ground.

Ward Stegerhoek: Martin was quite hands-on before the show, pulling at the straps on the clothes, adjusting the shoulder, fixing the hair before they went on the runway.

THE HOUR

Pierre Rougier: The idea that staging a show so far out of town might be an inconvenience never entered our minds.

Roger Tredre: I knew Paris well, and the location looked like a typical Paris street with terraced houses but with this space that looked like it might have been bombed in the war. The whole place was floodlit, with lots of people milling around.

Linda Loppa: There was a group of us from Antwerp — boutique owners, fashion students from the academy. We were like Margiela groupies! I should set the record straight, though: Martin was never a student of mine. But we did know each other from the Antwerp scene. Mary Prijot [5] was the head of the academy when he attended. Anyway, we weren't surprised by the neighbourhood. Us Belgians were quite used to the rougher lifestyle — Antwerp wasn't so luxurious and elegant then. I mean, sometimes the Royal Academy didn't even have electricity. When we arrived in the 20th there was a bit of confusion about the precise venue — I'm not sure I even had an invitation. Of course, later on Martin's invitations became highly collectible. So we just followed the other Belgians we recognised from their clothes — "Follow that one in black; that must be the way!" There was a cafe on the corner of a street nearby, and we gathered there drinking, talking. It was like a party.

There wasn't even a floor! It was like a trashy backyard.

Pierre Rougier: We never anticipated that all these people would turn up. Martin never let us hector people into coming. The attitude was, you can turn up, but if you don't, that's fine too. We were totally unprepared for the number that did.

Geert Bruloot: The narrow streets were filled with African people, Indian people, children, fashion editors, press and buyers. Martin and Jenny invited people from the neighbourhood too. They were a big part of the event.

Roger Tredre: There was no sense of trepidation. Maybe for someone like Suzy, chauffeur-driven, it was a bit strange. I recall being struck by the incongruity of these ladies in fur coats stepping over rough ground and slumming it a bit. It was quite amusing.

Suzy Menkes: I'm pretty certain I was taking the Métro in those days. I didn't think we were going to the ends of the earth for this show, or that anything unpleasant might happen to us out in the 20th. Absolutely not.

Roger Tredre: It wasn't clear where we were supposed to sit — were there even seats? Where were the models coming from? There were some children around, and locals began gathering to see what was happening.

THE SCRUM

Pierre Rougier: There was no seating plan. It was first come, first served. This was always the case; there was never a guest list like at other shows. But as all these people kept showing up, it became overwhelming.

Jenny Meirens: People were pushing and shouting that they weren't being treated particularly well, didn't have a seat... blah, blah. It was terrible. We didn't have the budget for VIP treatment.

Martin Margiela's Spring/Summer 1990 collection in Paris | Photo: Jean-Claude Coutausse

Geert Bruloot: Jenny was almost standing on the wall, shouting and directing people. It was quite hysterical.

Pierre Rougier: People were scaling the walls of the site to get in!

Raf Simons: I ended up gatecrashIng with Walter Van Beirendonck, who was holding a presentation in Paris. Martin's was the first fashion show I ever attended. I had the perception of them as big productions and quite glamorous — here, there wasn't even a floor! It was like a trashy backyard.

Pierre Rougier: By the time the show started, we didn't know who was an editor or who was a neighbour. We were like, "Let all the kids sit down!" and they did so along the runway, otherwise they wouldn't have seen anything. They were so excited, screeching and laughing.

Roger Tredre: And then at some point the show just started.

17 MINUTES

Frédéric Sanchez: There was a drumbeat on a loop from a live recording of the Buzzcocks that sounded very raw. I also had this recording of people playing music on the streets of different cities around the world — a tramp using some boxes as percussion and singing "Strangers in the Night". I think "Roadrunner" by the Sex Pistols was in there too. There were concerns about rain in the lead-up to the show, so I used this moment from Woodstock where the audience are chanting, "No rain! No rain!" There were probably 20 tracks used on the soundtrack, cut, repeated — using 10 seconds of one, 20 of another, mashed up together.

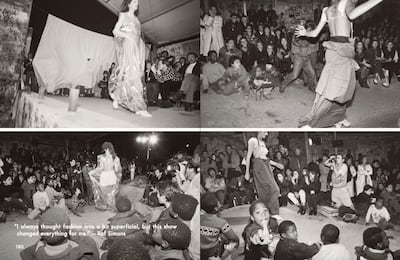

Raf Simons: As soon as the models started to come out, you knew something special was going to happen. They looked so angelic and alien.

Roger Tredre: They didn't move like regular models. They stumbled because they were picking their way across uneven ground.

Ward Stegerhoek: Martin didn't want the models to walk like professional ones, with their hips swaying and all that, and he'd spend quite some time with the professional ones before a show, instructing them. He wanted them to walk more like boys.

Kristina de Coninck: Martin just wanted us to be ourselves.

Geert Bruloot: There was a lot of black and white around the eyes, and these dark lips. The clothes were a continuation of the ideas expressed in the previous two seasons — the elongated sleeves; the narrow, rolled piqué shoulders; wide, tailored trousers; frayed and unfinished seams and hems. They even reused the exact same Tabi boots [6] that had been used in the Autumn/Winter 1989 show. But then there was this burst of volume from the waist, with canvas coats and skirts belted around it, worn over wide canvas trousers, and large canvas bags worn like panniers. It had a bit of a Victorian look to it.

Linda Loppa: The colours were mostly white and nude and looked so fresh in the midst of the graffitied and dilapidated surroundings. Tops were made from Franprix [7] plastic carrier bags — you know the French supermarket? I thought, Why a carrier bag? There were tops made from papier mâché, with metal breastplates... some models had bare breasts.

Kristina de Coninck: I was wearing a little white cotton vest top, a wide skirt, and underneath were large canvas saddlebags on either hip to create a hoop skirt. Each of the models wore the number 90 in some way — either sewn on to a piece of paper, stitched into the garment, drawn with a marker on the heel of a boot...

Martin didn't want the models to walk like professional ones. He wanted them to walk more like boys.

Suzy Menkes: It was a strange kind of bleak fairyland. The light cast an iridescent sheen on these plastic covers, and yet at the same time they were so banal — dry-cleaning bags.

Linda Loppa: The dry-cleaning bags were transformed into tailored coats, jackets, tunics and dresses, belted with ribbons, straps and metal fasteners. These were worn on top of oversized sheer slips with elegant drapery and pleating that looked quite disordered from a distance. But up close they were sublime. We loved it! I immediately bought one of those long canvas skirts.

Suzy Menkes: The dresses were actually surprisingly pretty. They were very floaty, semi-sheer, chiffon, worn like a milkmaid's but with no frills. They almost floated like a cloud on the body.

Jenny Meirens: There was never just one inspiration or precise idea in a Margiela collection. Martin would pull many different things together. Sometimes they would repeat over the different seasons.

Kristina de Coninck: The children couldn't sit still. They were fascinated by what was happening. We would smile down at them as we walked by; they'd smile back. We were all laughing. And then at some point they joined in and paraded alongside the models.

One of the models' boyfriends began to lift some of the children onto the models' shoulders.

Frédéric Sanchez: The music for the finale switched to classical music, harpsichord pieces by Rameau and Purcell.

Geert Bruloot: All the models and the backstage staff came out for the finale wearing the now-iconic blousons blanche atelier coats [8]. The models had confetti in their pockets and threw it into the air.

Jenny Meirens: One of the models' boyfriends began to lift some of the children onto the models' shoulders.

Raf Simons: I was so struck by everything I was seeing that I started to cry. I felt so embarrassed. I was like, Oh God, look at the ground, look at the ground, everyone's going to see you're crying — like, how stupid to be crying at a fashion show. Then I looked around, and half the audience was crying.

Geert Bruloot: It was all over in 17 minutes. We went backstage to see Martin and Jenny afterwards. It was in the days when Martin still stayed around after the show.

Pierre Rougier: Oh my God, it was such a happy, happy night. There was a huge sense of relief that we pulled it off. Martin was very happy.

Jenny Meirens: We felt very happy afterwards, enjoying the moment, drinking champagne from plastic cups.

Roger Tredre: I remember at the end thinking, This will be great copy!

THE REVIEWS

Jenny Meirens: We were shocked that the press wasn't very positive.

Pierre Rougier: Le Monde printed a scathing review.

Laurence Benaïm, fashion critic, Le Monde, 1986–2001: I thought it was like a parody of Comme des Garçons in the early 1980s. A little bit too postural. I don't expect a fashion designer to give me a lesson about what life is or what it should be. The clothes were perfectly cut but I didn't like the miserablist scenography. And I still hate drinking bad wine from cheap glasses!

Pierre Rougier: Libération was critical of how inappropriate it was to show designer fashion in a poor part of the city, saying it was exploitation of the neighbourhood and its residents. I read the article and thought, "Really? Is that what you got out of that show?"

Geert Bruloot: I think the industry loved it. We bought some pieces from it for Louis — the oversized slips with the plastic overlay, the canvas hip bags. For sure we bought the plastic hoods, as I still have one in my personal archive.

Roger Tredre: We trotted out of the 20th and felt we'd seen something that was special in ways we couldn't immediately define. That a young designer staged his show in such an unusual location and a lot of high-powered fashion editors actually turned up made this show unique.

Suzy Menkes: I was definitely fascinated and intrigued, and I certainly thought it was something new.

Roger Tredre: Whether the choice of venue had anything to do with reflecting the disintegration of the Berlin Wall [9], as some publications alluded to, I'm not sure. But the timing...

Jenny Meirens: Oh, no, no, no. That wasn't in our minds at all. Honestly, I think that people perceive it differently than we meant it. It's less heavy than people think.

THE LEGACY

Pierre Rougier: Well, it definitely ignited the cult of Margiela. The subsequent shows were just as weird, complicated and stressful to pull off. The sense that we had to outdo the last show with the next was never discussed. I'm sure Martin probably felt it, but he never said if he did.

Jean Paul Gaultier: I think that his way of staging shows and keeping out of the public eye was a reaction to what he'd seen while working for me. I was part of the first generation of designers to be mediatised, and I think that Martin wanted the exact opposite.

Roger Tredre: Right from the beginning, his approach to fashion was in line with the very pressing issue of sustainability, the need to recycle and the urgency of rethinking the whole system. Where to do that? Anywhere but the heart of the system.

Suzy Menkes: He was the beginning of making over clothes, of using existing garments and transforming them into something else. He was very far ahead of this trend.

Linda Loppa: It also showed that you could create a beautiful collection and put on a spectacular show with very little money. You can make garments that are elegant but rough and instinctive. You can have your friends around you to help and support. Interesting models can be found on the street. A simple statement of intent: "Come on! Do it!"

Raf Simons: As a student I always thought that fashion was a bit superficial, all glitz and glamour, but this show changed everything for me. I walked out of it and I thought, That's what I'm going to do. That show is the reason I became a fashion designer.

Jenny Meirens: We always wanted to be free, to be able to do what we wanted, to be spontaneous, to not respond to the impositions of the fashion world. We wanted to make a simple show, but for us this one was no more important than any other.

This article appears in the Spring/Summer 2016 issue of The Gentlewoman which hits newsstands on 19 February 2016.

FOOTNOTES:

1. Nina Nitsche was Martin Margiela’s design assistant for 19 years.

2. The group of fashion students who graduated from Antwerp's Royal Academy of Fine Arts in 1980 and 1981 (Ann Demeulemeester, Marina Yee, Dirk Van Saene, Dirk Bikkembergs, Dries Van Noten and Walter Van Beirendonck) was allegedly given the title by the British fashion press, who were unable to pronounce their names correctly.

3. Belgium’s once-thriving textile industry was foundering by the 1980s. Its government created the Golden Spindle prize in 1982 to promote new Belgian designers and textile manufacturers as part of a wider regeneration initiative.

4. New Beat originated in Belgium during the late 1980s. Characterised by a sludgy, heavy dance sound pitched at 115bpm, it also incorporated elements of Chicago house music. Clubs such as Ancienne Belgique in Brussels and Boccaccio in Ghent were at the centre of the New Beat scene.

5. Mary Prijot established the prestigious fashion department of the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in 1963. Ann Demeulemeester, Dries Van Noten and Martin Margiela all studied under her tutelage.

6. The Tabi boot is Margiela’s interpretation of the split Japanese tabi sock, which separates the big toe from the others and is worn with traditional thonged footwear.

7. Franprix is a French grocery chain founded in 1958 by Jean Baud. It has 860 outlets throughout the country.

8. The blouson blanche is a white work coat worn by the petites mains in the ateliers of haute couture houses. Margiela adopted it as a uniform for the company's employees.

9. Radical political change in East Germany in 1989 led to the removal of the blockade of West Germany on 9 November 1989. The wall’s official demolition didn’t begin until the summer of 1990 and wasn’t completed until 1992.

From where aspirational customers are spending to Kering’s challenges and Richemont’s fashion revival, BoF’s editor-in-chief shares key takeaways from conversations with industry insiders in London, Milan and Paris.

BoF editor-at-large Tim Blanks and Imran Amed, BoF founder and editor-in-chief, look back at the key moments of fashion month, from Seán McGirr’s debut at Alexander McQueen to Chemena Kamali’s first collection for Chloé.

Anthony Vaccarello staged a surprise show to launch a collection of gorgeously languid men’s tailoring, writes Tim Blanks.

BoF’s editors pick the best shows of the Autumn/Winter 2024 season.