The Business of Fashion

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

BERLIN, Germany — Just over a hundred years ago, the art critic Karl Scheffler famously observed that Berlin was a "city forever condemned to becoming and never to being." Even now, nothing looks quite finished and the city, again the country's capital, sits uncomfortably between its love of freedom and failure, and its desire to be taken more seriously by the wider world.

Thanks to its low cost of living, Berlin is a magnet for thousands of creatives. After the Second World War, state subsidies brought artists to West Berlin, while during the Cold War, city-wide exemption from military service attracted punks and left-wing rebels, who often squatted in empty buildings. And while the rest of Germany earned a reputation for hard-working efficiency — epitomised by the country’s large number of engineers and automobile manufacturers — Berlin became known for its art, music and clubbing scenes.

In a country home to relatively few major fashion brands — save for Adidas, Puma and Hugo Boss — Berlin alone has over 2,500 fashion businesses, many born from its renegade creative scene. And yet the city's most noteworthy labels — including GmbH, Ottolinger, 032c, Dumitrascu, Ximon Lee and Nhu Duong — all look to more established capitals to show and make their name. "They would never show in Berlin," says Mumi Haiati, one of Berlin's best-connected fashion publicists. "They use Berlin as a platform and space for their own creativity."

So, what’s the matter with Berlin?

ADVERTISEMENT

GmbH A/W'18 | Source: Courtesy

“The image of Berlin is what makes it and that image is that we're poor but sexy,” says Brigitte Zypries, Angela Merkel’s federal minister for economic affairs and energy. “I think Berlin is the liveliest city in Germany these days. We have a very lively start up scene here in Berlin and a lively culture scene, not just in fashion, but also in gaming and other creative industries, too.” The start-up scene has certainly helped transform the fortunes of Berlin, attracting a digitally savvy workforce and creating new spending power within the city.

Despite the city's love for secondhand clothes, its luxury retail sector is growing. "Seven years ago, when we launched, we had way less expensive labels," explains Herbert Hofmann, buying and creative director of Voo Store, a Kreuzberg concept store that sells a mix of established and emerging international labels like Raf Simons, Jil Sander and Rejina Pyo, alongside progressive local brands such as Goetze, GmbH and Reality Studio. "Our customer is now more interested in international fashion and come to our store to educate themselves." There's also Andreas Murkudis' concept store in northern Schöneberg, a spacious home to brands including Céline, Maison Margiela and Dries van Noten, as well as beauty products and design objects.

The trouble is that Berlin has a too-cool-for-school mentality and an unhealthy fetish for failure. “Berlin is a brand and everyone thinks it’s cooler than it is,” says Jessica Hannan, the British-born fashion director of Sleek, a Berlin-based art and style title. “Berlin capitalises on its own brand and everyone thinks they know what it is, but the truth is that people come here and never leave the perimeters of Soho House — or Berliners are embarrassed to be in fashion because they want to be artists. The reality is that the German market is much more conservative than what people perceive to be quintessential Berlin.”

For Andrea Dumitrascu, Berlin can be a graveyard of ambition. “I've been observing a lot of waves of people coming in, who are excited and cheerful and talented and interesting, but it's a city that will swallow you,” says the designer, who moved to Berlin 15 years ago and joined the art group The Honeysuckle Company before becoming a fashion buyer. “There is no urge or pressure to do anything here and there’s nothing going on. You’re just creative, but then you don't get things done. Berlin has potential, but no structure to support it.”

There is no urge or pressure to do anything here and there's nothing going on. You're just creative, but then you don't get things done.

“Looking from the outside, a lot of people see Berlin and they see 032c and GmbH and all of that, but all of that has nothing to do with the actual fashion scene in Germany,” points out Alexandra Bondi de Antoni, editor-in-chief of i-D Germany, whose audience is 50 percent Berlin-based. “Anyway, no one really cares about what you wear in Berlin.” She agrees with Dumitrascu’s comments: “Compared to London, where you have to survive, Berlin is so cheap and a lot of designers don’t have that fight, so they don’t get that far.”

Stefano Pilati, former Yves Saint Laurent and Ermenegildo Zegna Couture creative director, moved to Berlin five years ago. "It's a city where you enjoy the lack of pressure, but what you do with this lack of pressure is very subjective," he says cautiously. Although Pilati is said to be working on a fashion project that will launch later this year, he is keen to stress that Berlin is not a fashion capital because "no one cares" about fashion in the city. "I don't care in the sense that I can see on the street or at the club what looks good or fashionable, but it's not an expression of aspirational people."

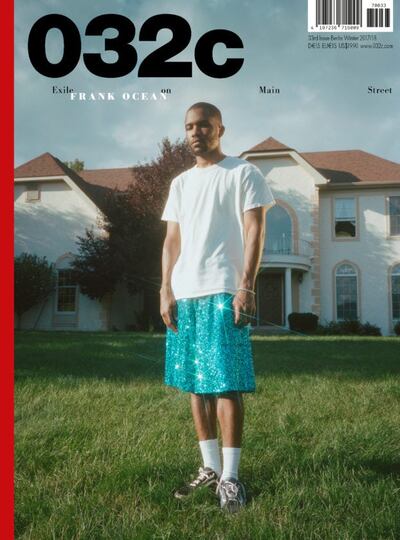

Frank Ocean on the cover of 032c | Source: Courtesy

ADVERTISEMENT

Perched in their low-ceiling sitting room, which is covered from floor to concrete ceiling in violet Vorwerk carpet, Joerg and Maria Koch are surrounded by art and Supreme artefacts. The couple behind 032c, the magazine cum fashion label that recently staged its first show at Pitti Uomo, have an apartment and office space in St Agnes, a converted brutalist church in Kreuzberg. Joerg is the editor; Maria is the designer.

“The most punk thing you can do in Berlin is to be successful,” says Joerg. “The whole culture of failure is a cheap exit not to go for your dreams. Having failures is important but in Berlin it's a sick celebration of failure. You're not allowed to talk about success. The fact that we're successful is a poo-poo for people; it's not expected of a cultural title. But the more successful we are, the more [creative] freedom we have.”

"When we started out, fashion with a capital 'F' was a fantasy," he continues. "We didn't see stuff like Yves Saint Laurent, Chanel or Dior, and that obviously was really helpful for us to develop our own identity, but we're now at the stage where we could actually benefit from a bigger commercial structure." Part of the problem, however, is that Germany's biggest fashion companies are spread out across the country, which makes it difficult to create a hub in Berlin. "If you had all of the companies in one place, it would be incredible, because then avant-garde brands would have the context of how to develop," adds Joerg.

“Berlin has never had an active garment-making industry,” agrees Ximon Lee, the gender-neutral designer who shows in Milan. “Even arriving at the airport, it feels like the '80s. Sometimes you arrive in the old part of the terminal and there is no elevator and you have all your samples to carry. Other times, things get stuck in customs and it takes weeks and so much paperwork to get them back.”

“Berlin and its slightly anti-attitude inform everything we do, from how we cook communal lunches every day in the studio to how we design,” say Benjamin Alexander Huseby and Serhat Isik, the designers behind GmbH, which has been referred to as Berlin’s answer to Vetements. But their label, which earned an LVMH Prize nomination last year, is more rooted in the collision of immigrant culture and German severity (Huseby is part Pakistani, part Norwegian; Isik is part German, part Turkish) as well as Berlin’s harder-faster-louder techno clubs than the irony of elevating ordinary clothes.

The most punk thing you can do in Berlin is to be successful ... Having failures is important but in Berlin it's a sick celebration of failure.

GmbH’s Paris Fashion Week shows and advertising campaigns reflect the multiculturalism of Berlin, which has long been home to a hodgepodge of Turks, Polish and Vietnamese immigrants, as well as more recent arrivals: left-wing rebels from conservative southern Germany, start-up entrepreneurs and Anglo-American creatives. But the disadvantage of being a growing brand based in Berlin, say Huseby and Isik, is that “you are somewhat disconnected to the world, and there is hardly any professional fashion network or qualified people.”

“It is very important for us to show our collections during Paris Fashion Week, because the whole industry is present there these days, and some of those people might not come to Berlin. We have to go there to meet them in person. But where we work and live during the rest of the year doesn’t really matter for us at this point,” say Cosima Gadient and Christa Bösch of Ottolinger, known for its textural womenswear.

Halle am Berghain, an increasingly popular venue for fashion | Source: Courtesy

ADVERTISEMENT

Commerce is front and centre at Berlin Fashion Week, however, which was launched by IMG in 2007 and has been the subject of a much-anticipated revamp by the newly-formed Fashion Council Germany, a not-for-profit organisation with the ambition of becoming something similar to The Council of Fashion Designers of America or The British Fashion Council. Formed to provide a better support structure for German designers, the council was tasked with turning around a fashion week that had been ridiculed by fashionable Berliners for its ill-placed commercial sponsorships and lack of renowned designers. Hugo Boss and Escada, two of the schedule's biggest names, jumped ship three years ago.

Matters seemed to improve when Berlin Fashion Week sponsor Mercedes-Benz parted ways with IMG, which most local players described as an obstacle to progress. This time around, the white tents at the Brandenburg Gate were gone, and replaced by the automobile brand’s fashion and digital activation venue at E-Werk, an events venue near Checkpoint Charlie that was once a world-famous techno nightclub, and today is more discrete and less branded alternative to the previous official venues. “London, Milan and Paris have their own images, but for decades they have had council-owned fashion weeks — ours only started two years ago,” argues Caroline Pilz, head of fashion sponsorship and product placement at Mercedes-Benz . “Also, the reputation in the past was that it was too commercial, but you can’t complain about it being too commercial and then have no sponsors and support.”

"I like the rawness and the ugliness of Berlin and I think it's the perfect ground for creativity," said Christiane Arp, the Munich-based editor-in-chief of German Vogue and president of Fashion Council Germany. "I was in New York in the '80s and it is the same energy. It's also an international cosmopolitan city. I see it as [Germany's] melting pot." As part of Berlin Fashion Week, Arp curates an exhibition space called 'Berliner Salon' with up-and-coming Berlin-based designers on show. "This is a growing market that is becoming more and more interesting for international retailers. 032c and GmbH, they're still German even though they show in Paris or Florence. If there was a wish I could make, it would be that in five years' time, they all show in Berlin."

https://www.instagram.com/p/BU04MQTAYOt

One of Arp’s selected designers, William Fan, does show in Berlin and hasn’t a negative word to say about the experience. Fan’s elegant ready-to-wear sits alongside Céline in KaDeWe, Germany’s biggest department store, where he has a sell-through rate of 70 percent. Based in Mitte, Fan produces his collections in Hong Kong and shows in Berlin, because his customer is “100 percent German.” He has just opened a store in his neighbourhood, which is also home to Soho House and The Store, its ground-floor boutique. “South Germany is where the money is, but they’re based everywhere — I have a customer in Cologne who is one of the biggest art collectors,” he enthuses. “I know there are problems [with Berlin Fashion Week] but there are a lot of people here, including important buyers in this market. I like to keep it local and get the right people.”

The reputation [of Berlin Fashion Week] in the past was that it was too commercial, but you can't complain about it being too commercial and then have no sponsors and support.

Dorothee Schumacher, a fellow Berlin-based designer who has been in business since 1989, points out that showing in Berlin allows her to get a head start in the season and have more time to prepare for sales appointments in Paris. She currently has 600 retail partners in over 45 countries, and says that she is still establishing herself in the US market.

Trade shows are also an integral part of Berlin Fashion Week. Bread and Butter was perhaps the city's best-known trade fair, but in 2015 it was acquired by Zalando and turned into a public-facing "fashion festival," losing its industry kudos. According to Anita Tillmann, managing partner of Premium Exhibitions and founding board member of Fashion Council Germany, the four trade shows that currently exist alongside Berlin Fashion Week have more than 3,000 collections and 60,000 visitors from all over the world. Tillmann rebuffed the notion that a clash with the menswear shows in Milan and Paris would deter industry professionals from Berlin Fashion Week, adding that Premium has just invested €2.5 million in a digital platform to ease communication and transaction between exhibitors and visitors. "We have to be prepared and think in a bigger perspective," she says.

‘Mumi Haiati and Robert Grunenberg (top and middle centre) with friends’ | Source: Courtesy

“Two or three years ago, I wouldn’t have done this,” said Damir Doma during a walkthrough of his street-cast Berlin Fashion Week show, staged at Halle am Berghain, the gay sex club and iconic techno venue on the border of Kreuzberg and Friedrichshain that is a concrete cathedral to Berlin’s nightlife, as part of Mercedes-Benz's 'Fashion HAB' space. The designer has never showed in Berlin before and although he is from Southern Germany, his only connection to the capital is that he briefly studied there. “You can’t do it two or three seasons in a row, and we’ll be doing showroom appointments in Paris so that we don’t miss out on reviews and crucial press. Next season, we’ll go back to showing in Milan.” What attracted him to be a part of the schedule was the venue, and the opportunity to show in an authentic space with a thumping soundtrack by Berghain’s resident DJs. Despite not wanting to participate in it beyond a one-off show, he’s positive about the future of Berlin’s fashion scene. “IMG pulling out of Berlin Fashion Week was the first positive thing and also the start of the Fashion Council Germany.”

There’s certainly an air of optimism among many designers. “With new money coming into the city, start-ups booming and rents getting more expensive, Berlin is currently in the process of redefining itself,” says Nhu Duong, a Swedish designer based in Berlin, whose dark unisex ready-to-wear is often infused with vinyl and streetwear references. “Just look at the long lines outside of the nightclub Berghain and you can see how commercial success and cultural integrity are flirting with each other.”

Later this year, Berghain will also play host to a different kind of fashion event that could become a cooler, more international alternative to Berlin Fashion Week. Reference Berlin will be a sort of festival for fashion, art and design, curated by Hans Ulrich Obrist and 032c. Coinciding with Berlin's well-attended Gallery Weekend in April (which doesn't clash with any major fashion weeks), the event is being organised by Mumi Haiati and Robert Grunenberg, a Berlin-based art historian and curator. Reference will include major international brands such as Gucci and Wales Bonner, as well as other prominent names in art, fashion and design yet to be announced. It will comprise of installations, screenings, panel discussions and a high-profile party — and its emphasis on creativity and culture aims to be something of an antidote to Berlin's official fashion week programme. "It's fundamentally a storytelling platform where art, fashion, commerce and technology are natural extensions of one another," explains Haiati. "It will mirror the spirit of Berlin's utopia, where creativity, experimentation and freedom of expression flourish."

Disclosure: Osman Ahmed travelled to Berlin as a guest of Mercedes-Benz.

Related Articles:

[ Why Isn’t Germany a Bigger Fashion Player?Opens in new window ]

[ Joerg Koch Defies Content-Commerce Orthodoxy Opens in new window ]

This week’s round-up of global markets fashion business news also features the China Duty Free Group, Uniqlo’s Japanese owner and a pan-African e-commerce platform in Côte d’Ivoire.

Affluent members of the Indian diaspora are underserved by fashion retailers, but dedicated e-commerce sites are not a silver bullet for Indian designers aiming to reach them.

This week’s round-up of global markets fashion business news also features Brazil’s JHSF, the Abu Dhabi Investment Authority and the impact of Taiwan’s earthquake on textile supply chains.

This week’s round-up of global markets fashion business news also features Dubai’s Majid Al Futtaim, a Polish fashion giant‘s Russia controversy and the bombing of a Malaysian retailer over blasphemous socks.