The Business of Fashion

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

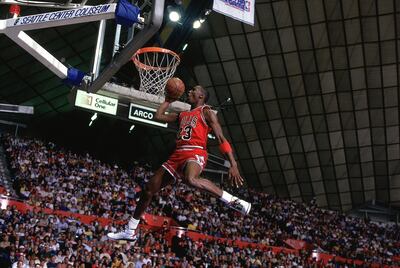

SHANGHAI, China — A bespectacled lawyer clothed in black robes holds an oversized cardboard placard with a famous image of Michael Jordan playing basketball. His body moves in one direction while he holds a basketball at full extension outstretched the other way. On top of that image, she slides the logo of China's Qiaodan Sports company, a red figure on a white background which fits perfectly inside the outline. It is undoubtedly the basketball superstar's silhouette.

In Hollywood, this scene would be a neat piece of courtroom theatre drawing gasps from the gallery. In China, it is a short animated image that went viral on Weibo and other social media platforms just as the country's Supreme People’s Court in Beijing heard an appeal in the long-running case of Michael Jordan vs Qiaodan Sports. The gif seemed to pre-empt the court ruling.

A gif image that circulated on Chinese social media during the Michael

Jordan vs Qiaodan Sports trial | Source: Weibo.com

Headlines declared victory for Jordan in this latest case. In April, after an eight-year legal battle, the Chinese company Qiaodan lost the right to one of its trademarks, the combination of its logo (the silhouette of Jordan that Qiaodan has argued was actually an unrelated figure holding a table tennis paddle) and its company name in pinyin, the romanised form of the Chinese language. It is important to note that Qiaodan is a transliteration of Jordan’s surname commonly used by Chinese people and media reports when referring to the basketball star.

ADVERTISEMENT

However, the real outcome of this ruling, as with almost everything about this case, is more complicated than recent headlines would have people believe. At present, there remains no clear overall winner or loser.

The court ruled that the silhouette alone did not violate Jordan’s portraiture rights, because it does not show any defining individual features, meaning Qiaodan can continue to use it as their logo. Qiaodan can also continue to use the pinyin version of its name “Qiaodan” — just not the two elements together.

But will this latest ruling — or for that matter any future battles over Michael Jordan’s name in Chinese courtrooms — make any difference to the passionate consumer base that the Nike-owned Jordan brand is cultivating in China?

Understand Consumer Sentiment Before Going to Court

“I think to the Air Jordan consumer, [the legal case with Qiaodan] doesn’t make a difference,” explained Chris Wang, founder and chief executive of Chinese streetwear media platform Nowre, a leading figure in China’s streetwear scene for more than a decade.

"Maybe the young kids in China are not going that deep in the culture [of streetwear or basketball] but they know what kind of product will make you cool — they know it's cool to wear Jordan Ones, but wearing Qiaodan is not cool," he added.

This should be a relief to Jordan and Nike because, after years of court battles, Michael Jordan has failed to overturn 74 of Qiaodan’s trademarks, according to legal experts and a statement supplied to BoF by Qiaodan Sports. BoF also reached out to Nike and Michael Jordan for comment, but neither responded prior to publication.

Most of these legal losses stem from the fact that there is a five-year statute of limitations on challenging trademarks and Qiaodan has owned some of these trademarks in the Chinese market for decades. The combination of the silhouette and pinyin logo was more recently filed, which is why it was more easily challenged from a legal perspective.

ADVERTISEMENT

“The Supreme Court verdict has ruled this logo be retried by the trademark office, but we don’t know what the retrial will be like, and we are not sure whether Jordan will sue Qiaodan Sports again after the retrial,” said Xu Chendi, a lawyer for the Beijing Zhongwen Law Firm.

Michael Jordan has failed to overturn 74 of Qiaodan's trademarks.

This year's case was only the second in which Michael Jordan has won a Supreme Court case against Qiaodan. In 2016, the court decided that the use of the Qiaodan name in Chinese characters (乔丹) was a violation of Jordan's naming rights, but that the Chinese company could continue to use the pinyin version in Roman letters, 'Qiaodan'.

Last year, Qiaodan applied for 12 new trademarks involving Jordan’s name in Chinese, including “Qiaodan Superdry.” These are still waiting approval, according to the Trademark Office of National Intellectual Property Administration. Clearly, the latest case is far from the end of the road for the epic Jordan vs Qiaodan battle.

“Any one case in the context of this case overall isn’t that significant,” explained Professor Laura Wen-yu Young, who has taught courses on International Intellectual Property at universities in both the US and China. “Michael Jordan won this one case that is very narrow and doesn’t change Qiaodan doing their business and [so] we will continue to see Qiaodan’s [version of the] ‘jumpman’ logo being used.”

China is a ‘First to File’ Jurisdiction

The genesis of the case of Michael Jordan versus Qiaodan Sports goes back much further than the first court action in 2012. The narrative tracks a close course with the evolution of consumer culture and branding in China over the past two decades.

The basketball prowess of one Michael Jeffrey Jordan was known worldwide in the 1980s and 1990s, and he was first shown on Chinese television back in 1984 playing for the US team in the Olympic games. In China, people referred to Jordan by a transliteration of his name, Qiaodan (pronounced chee-ow-dan) and newspapers wrote Jordan’s Chinese name in characters that represent this pronunciation (乔丹).

In the 1990s, a sportswear manufacturer based in the southern province of Fujian, decided to start its own brand, after making low-cost sportswear for foreign companies. In the early-2000s that company became known as Qiaodan Sports. Over the last 20 years Qiaodan has registered more than 200 trademarks in some way related to Michael Jordan, including trademarking both his sons’ names.

ADVERTISEMENT

"[Even today] this is a major difference between Chinese brands and international brands," said Wang, who previously worked for W+K, the advertising company used by brands such as Nike and Converse. "Chinese brands are good at making business but [international brands like] Nike make a branding story, plus the business."

Qiaodan was able to file so many trademarks related to Michael Jordan in China because it is a “first to file” jurisdiction, meaning there are not the same restrictions as there are in the US, which requires companies to prove prior use or intent to use a trademark before it can be registered.

Though the company was unaffiliated with Michael Jordan, one of the world’s most famous athletes, there is little doubt that the use of the name helped propel the brands’ success. Interestingly, there have been several studies in China concluding that there is not a lot of confusion about the brand being affiliated with Jordan among Chinese consumers. But branding often plays on valuable subconscious associations – which, according to Jordan’s supporters, is why Qiaodan wanted to use the name in the first place.

Michael Jordan in action, making a dunk during All Star Weekend in Seattle, 1987 | Source: Getty Images

However, Wang says that people might be surprised at how much Nike’s Jordan brand, with its famous silhouette of Michael Jordan’s “jumpman” logo, has actually been divorced from Jordan the man in the minds of Chinese consumers today.

“I was born in 1984, so I remember watching Michael Jordan, winning games with the last shot, but young kids today, they don’t remember him, what talent he had. The kids are only into the shoes,” he said.

Avoid the Statute of Limitations Trap

Things were different in the years in which Qiaodan Sports was rising. The company last publicly released earnings in 2011, when it claimed operating income for 2010 of almost three billion yuan (or $420.62 million at current exchange rates). The first decade of the 21st century in China was a time when brand building just wasn’t a high priority for local brands.

“This period, between 2000 and 2010, when Qiaodan came up, was the peak of China’s shanzhai consumption,” explained Yang Zengdong, a post-80s generation mother-of-two, who is now based in Shanghai, but grew up in a lower tier city in Hunan province and first came across the Qiaodan brand when she went to university in Xi’an about 15 years ago.

Shanzhai, though it literally translates as “mountain fortress,” refers to lookalike products and brands — counterfeit Prada purses sporting ‘Praga’ labels; fried chicken chains decked out in red and white called ‘DFC’ — that were once all the rage in China, but are now viewed as something of a joke by an increasingly sophisticated and discerning consumer base.

“Back then, companies didn’t build up a brand, nurturing it like it was a child. They didn’t know what the situation would be in three years, so just making money right now was enough [and consumers seemed to like] names that sounded foreign,” she added.

She remembers buying a Qiaodan bag for a little over 100 yuan ($14 at current exchange rates) when she was a university student and says the brand has traditionally been thought of as similar to domestic market leader Anta, founded in 1994, in terms of positioning and price.

By 2007, with an eye to expanding the presence of its Air Jordan brand in China, by then a burgeoning consumer market, Nike tried to register trademarks for the Chinese and pinyin versions of Jordan’s Chinese name (they had earlier successfully trademarked the English versions) only to find they had already been taken by Qiaodan.

No one should lose control of their own name... my case shows that China recognises that this is true for everyone.

This left Nike in a quandary, with the Chinese legal system’s five-year statute of limitations on many of these trademarks already expired, legal action was unlikely to succeed, but ceding the Jordan name to another company was also anathema to both Nike and Jordan himself.

“No one should lose control of their own name, and the acceptance of my case shows that China recognises that this is true for everyone,” Michael Jordan himself said at the beginning of the first legal action against Qiaodan, in 2012. “After all, what's more personal than your name?”

Litigation Delays a Competitor’s Growth

Eventually, it was another consideration that seems to have pushed Michael Jordan to take legal action in China — the prospect of Qiaodan Sports listing on the stock market, which looked set to happen in 2011.

“Qiaodan was about to go public, [Nike and Michael Jordan] were concerned that it could be a huge global brand. I would guess that Nike also thought they would get a lot of backing from the US government, because during trade negotiations, sometimes you can get a government like China to put its thumb on the scales and make things happen, but certainly that didn't [happen for Nike] in this case,” Professor Wen-yu Young said.

The ongoing legal dispute has prevented Qiaodan's IPO, with regulators citing the ongoing legal cases as a significant risk factor to shareholders if Qiaodan were to go public. The limits to fundraising caused by its inability to go public together with the evolution of Chinese consumer culture away from shanzhai brands, has undoubtedly hindered the company in terms of its ability to grow over the past decade. In the meantime, it has seen international sportswear brands, including Nike and Adidas, as well as local players such as Li Ning and Anta, build brands worth billions of dollars.

“Even if he lost one case after another, as long as he prevented Qiaodan Sports from rising further, Michael Jordan can consider his opponent the de facto loser,” wrote Fang Zhengyu, a sports commentator, in a column at national Chinese media outlet Phoenix News.

The rising success of the actual Jordan brand in China must also sting Qiaodan. Though it doesn’t break out China market figures, the Jordan brand generated $3.1 billion in global sales in Nike’s 2019 fiscal year. That total accounted for about eight percent of the apparel giant’s overall sales.

"In China last year, the [market] for sneakers became huge," Wang said, adding that Jordan, and in particular the models Air Jordan One and Air Jordan Four, have become special beneficiaries of that trend.

The Jordan brand has been particularly focused on expanding within China in recent years, opening its largest Asian store in Chengdu in 2017 and even recently expanded into Qiaodan’s home province of Fujian.

The popular ESPN Films and Netflix documentary mini-series “The Last Dance,” which chronicles Jordan’s last season with the Chicago Bulls, will no doubt also help propel the brand forward further. It's already proved popular on various Chinese streaming sites, where it is shown with Chinese subtitles.

A lot of companies still don't want to do a Chinese [brand name] version and I think that's a mistake.

Cowen & Co. analyst John Kernan believes the Jordan brand has potential to grow much further in China because the sneaker category has yet to peak and the sportswear sector more broadly continues to gain strength. "Sneakers is going through one of the biggest renaissances of its history and not showing any signs of moderating," he said.

Indeed, in a post-coronavirus market in which health and wellness are at the top of Chinese consumer agendas, few are worried about a dent in enthusiasm.

Register Trademarks Early to Attract Finance

The legal battle between Nike-owned Jordan and Qiaodan has garnered attention because it represents a battle of the titans, but the case remains relevant for other fashion and beauty players of all sizes.

According to Professor Wen-yu Young, there is still a hesitancy for international brands to file Chinese trademarks early in their life cycle, when money is being funnelled into production and marketing and a home-market trademark.

“[Companies] still make the mistake of saying, ‘I don’t really have a market in China,’ which is a huge mistake. So many obscure companies in the US and all over the West probably do sell indirectly into China, via a middle person or online,” she explained.

The second mistake companies are still guilty of, even after Nike’s high-profile example, is not registering their brand name in Chinese characters and pinyin.

“A lot of companies still don’t want to do a Chinese [brand name] version and I think that’s a mistake,” Professor Wen-yu Young said. “A lot of times it’s easier for Chinese to type two characters in Chinese than to spell your name in English letter combinations that will be hard for them to remember.”

Registering a trademark in China costs about $600, she adds. It is a small price to pay compared with $5,000 to $10,000 for each legal hearing to take action against squatters or opportunists in China who pounce on trademarks of Western brands that might not even be aware they have found a niche audience in China.

For smaller companies still not convinced, Joe Simone, founder and partner of SIPS, advisors to companies on intellectual property (IP) rights in China since the mid-1980s, points out that any investor worth their salt is going to immediately ask questions about international IP and trademarks before pouring money into a fledgling fashion or beauty brand.

“They all think securing their brands from pirates is going to be a money pit and they understandably prefer to put every dime into marketing and sourcing of product instead,” Simone said. “But when a start-up fashion brand is in need of capital, getting their trademark rights in order can be a smart investment. No-one tells them this until it’s too late.”

Related Articles:

[ How Are Sports Brands Marketing Without Sports?Opens in new window ]

[ Nike Engineering a Rebound for Jordan BrandOpens in new window ]

[ Michael Jordan Scores China Legal Win for His Chinese NameOpens in new window ]

[ Michael Jordan's First Air Jordan Sneakers Sold for Record $560,000 at Sotheby'sOpens in new window ]

This week’s round-up of global markets fashion business news also features Latin American mall giants, Nigerian craft entrepreneurs and the mixed picture of China’s luxury market.

Resourceful leaders are turning to creative contingency plans in the face of a national energy crisis, crumbling infrastructure, economic stagnation and social unrest.

This week’s round-up of global markets fashion business news also features the China Duty Free Group, Uniqlo’s Japanese owner and a pan-African e-commerce platform in Côte d’Ivoire.

Affluent members of the Indian diaspora are underserved by fashion retailers, but dedicated e-commerce sites are not a silver bullet for Indian designers aiming to reach them.