The Business of Fashion

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

NEW YORK, United States — Ralph, Calvin, Donna. Tommy, Michael, Tory. Fashion in the United States has long been dominated by superstar designers whose brands are almost synonymous with their first names.

Joseph Altuzarra, on the other hand, may never achieve this level of renown. For one, he has chosen to leave his given name off his brand, effectively allowing the label and its clothes — rather than the man — to take centre stage. "When we see new talent come to fashion, it often feels as if they come to the industry because they want to be famous," says Neiman Marcus fashion director Ken Downing. "Joseph came to the industry because he loves the craft of creating clothes. He loves dressing women. His fame has come not because he put himself front and forward, but from his creations."

And yet, the 33-year-old Altuzarra, who founded his business in 2008, has steadily risen up fashion's ranks, positioning his brand in a way that astutely balances creativity with commercial savvy. Nearly a decade in, when many labels start to lose momentum financially or aesthetically, there is no question of whether Altuzarra will survive. It's more about how far the label can go.

“I think there are so many really great examples of success at different levels, and it’s about how you define it,” the designer says, sitting in his Howard Street office just a few weeks before moving his company, which now has more than 30 employees, further south to a bigger, better space in the Financial District. “Dries is incredibly successful. He’s outside Antwerp, independent and happy. That’s a wonderful example of success on a level. Same with Alaïa,” he continues. “But I have the ambition and the drive to build this into something big — I hope.”

ADVERTISEMENT

To do that, Altuzarra has taken a measured, in-no-rush approach to everything from hiring to product development. Consider the introduction of handbags in 2015, which happened a whole seven years after he photographed his friend and muse Vanessa Traina in his first, still-recognisable collection. "Leather goods was something that he was interested in long before, as a business, we felt it was the right time to launch it," notes Karis Durmer, who joined as chief executive in 2011. "But we wanted to make sure we had the right product, and that it was the right moment for the brand."

While handbags are still a nascent business, it's one that the company is willing to put muscle behind. Its first serious advertising campaign — which launched for Autumn/Winter 2016 and features still-life vignettes shot by Robin Broadbent and art directed by frequent collaborator Thomas Lenthal — was built around three of the season's handbag styles. The campaign takes cues from the work of French artist Carmen Almon, who shapes botanical sculptures out of copper sheeting, brass tubing, steel wire and enamel.

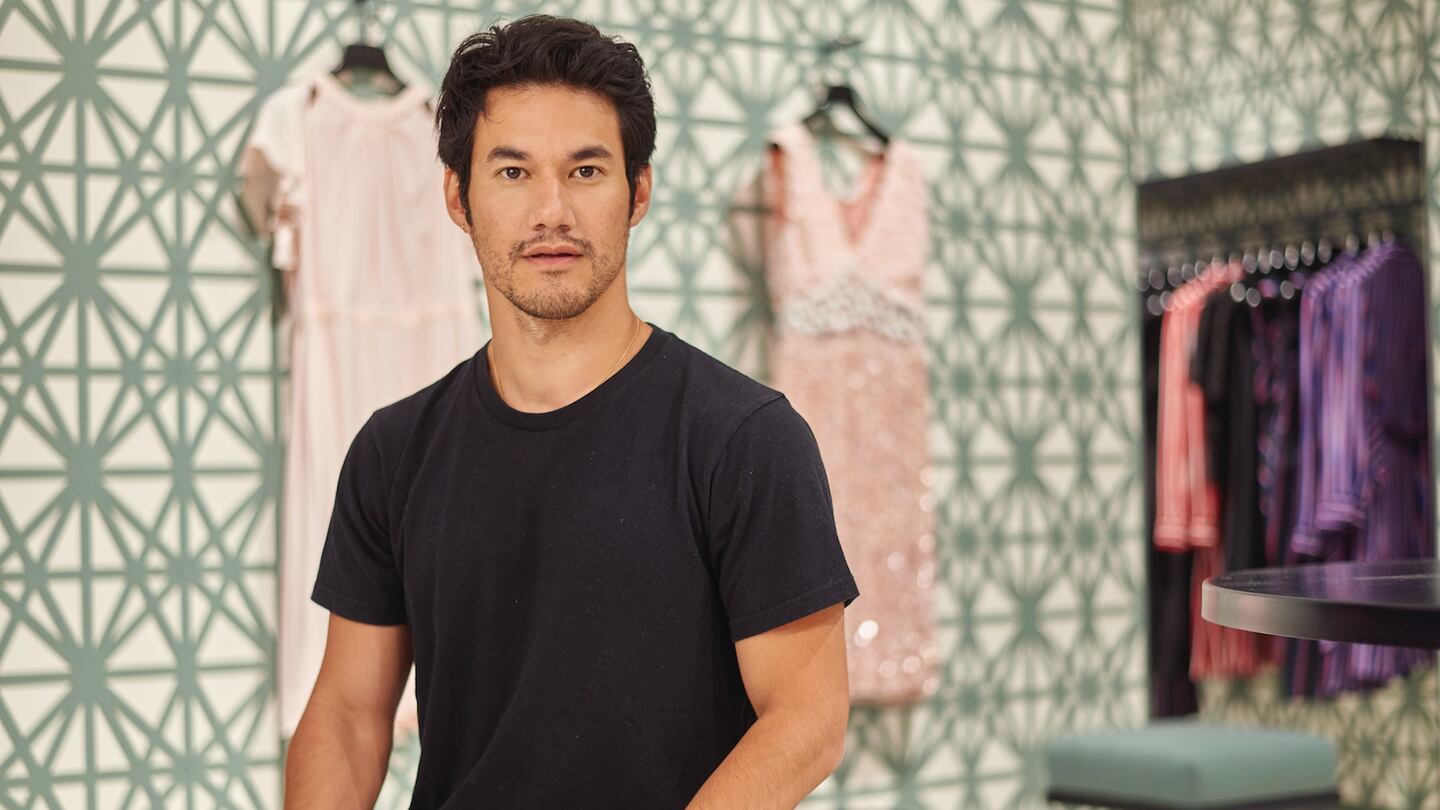

Altuzarra's new shop-in-shop in Saks Fifth Avenue | Photo: Richie Talboy for BoF

In turn, Altuzarra commissioned Almon to create a piece for his new shop-in-shop on the recently opened fourth floor of Saks Fifth Avenue's Manhattan flagship. Perched between Marni and Brunello Cucinelli, the 400-square-foot space is the brand's first-ever direct retail concept, inspired by the winter gardens often found in 19th century European homes. The designer went to great lengths, in collaboration with Lenthal, to transport the client into his world, which draws heavily from his heritage. (Born and raised in Paris to a French-Basque father and Chinese-American mother, Altuzarra attended the classic liberal arts college Swarthmore outside of Philadelphia before heading back to Europe to apprentice under patternmaker Nicolas Caïto, eventually becoming Riccardo Tisci's first assistant at Givenchy.)

Consider the begging-to-be-roughed-up Moroccan-tile flooring, laid out in a grid with the letters A-L-T-U-Z-A-R-R-A. That grid — now a brand signifier — is also woven into leather handbags, and worked into the company’s look books and fashion week invitations. “We started playing with it in bags, and it ended up being something I really liked,” the designer says. “I think what’s nice about this is that it has an interesting backstory that’s not necessarily in your face.”

To be sure, Altuzarra’s own backstory is a major part of what defines his fashion. “We have four brand pillars,” he says. “The first is the French side, and that is really a part of who I am — part of my upbringing, but also aesthetically very important. It’s where the sophistication and this slight nonchalance and seductive approach comes in; something that feels a little undone, a bit not-overthought.” The second is his American-ness: “The ease of clothing, the pragmatism, the sportswear. I think the same way that I’m half-French and half-American, so is the brand.”

The third part, he says, is sensuality. “The collection always has to feel seductive,” he reasons. “There is a sort of sexual confidence.” And finally, there is craft. “It's about looking at different communities, different areas of the world and trying to play with the idea of craft — and traditional craft especially — as a gateway to thinking about identity.”

It's always difficult to have a brand predicated on cool, because there's always going to be something cooler or younger and newer.

These elements serve as a rubric for every piece of Altuzarra. And it helps to explain why and how the designer has excelled in so many categories, with so many different types of clients. The business, according to Durmer, does not rely too heavily on one signature, one hit. Instead, there are several recognisable styles: The high-slit pencil skirt, the expertly tailored blazer, banker-cuff shirtdresses and most recently, the saddlebag. “It’s always difficult to have a brand predicated on cool, because there’s always going to be something cooler or younger and newer,” Altuzarra says, explaining the approach. “That’s something I think about a lot. I never wanted to be the cool kid. Because it’s very hard to evolve from it.”

ADVERTISEMENT

By all accounts, the approach is working. “Joseph is making women feel good. We know that because we’re seeing steady growth,” Durmer says. “Not seasonal spikes.” The company, which sold a minority stake to Kering in 2013, does not disclose revenue figures, although Durmer says that sales have grown 350 percent since the deal was put in place, outperforming initial projections.

Just how far the label can grow from here is another question, however. "I think the landscape for designers in retail right now has changed dramatically and is in flux. I’m not sure we’ll ever see another wave of Ralph and Calvin and Donnas in America," says retail consultant Robert Burke. But I think what we will see are very strong, focused America brands that can be big. That moment of mega, billion-dollar brands might be over, but it doesn’t mean that someone can’t build a $500 million business." To Burke, Altuzarra is well positioned to achieve this. "I have full confidence that he’s going to be leading the pack of American designers and that he also has the understanding of the business to do it," Burke says. "I'm optimistic about Joseph, and I would say that the retailers that are very attuned to the industry feel the same. He’s really created a unique position in the market."

Right now, market sources suggest that the business is still making under $20 million a year. “We are in the range where $50 million is our next hurdle,” Durmer says. “When you’re growing a company, you look to hit your $15 million mark, then your $50 million mark, then $200 million. And then you’re trying to be, you know, half a billion dollars. Those are steps that you want to take, and we’re on a step where [$50 million] is on our horizon."

To get there, Altuzarra will have to continue turning out creatively-forward and critically-lauded collections that, at the same time, drive home his big picture message.

This is where his roots come into play. He appreciates “fashion” in the way the French do, but “clothes” in the way Americans do. “There is an instinctive awareness that makes his work very sophisticated,” Lenthal says.

But perhaps most importantly, he is not afraid of his customer. While the designer is inspired by early supporters including Carine Roitfeld and collaborator Traina — whose narrow, impossibly chic figures are unattainable for most — he understood from the beginning that this would, in general, not be the person buying his clothes. In 2011 at a Barneys New York event, he spoke of wanting to dress Meryl Streep and Diane Keaton's characters in a Nancy Meyers movie, and that is still true today. Although now, it's less about age and more about a state of mind. The Altuzarra woman is a woman who wants to feel confident, sexy, but also appropriate. "There is a very honest lens through which Joseph looks as his customers," Downing says. "What they're interested in — and what they're not interested in — informs collections season after season."

And in the grand tradition of Michael Kors, whose talent for charming sales associates at store clinics and fitting clients at trunk shows serves as a shining example for the entire industry, Altuzarra relishes his time with customers. "I know [many] designers don't like doing trunk shows or meeting clients, but I love it. You end up talking through the issues, whether it's their arms or their stomach being a little soft. Or the fact that their breasts aren't as firm as they used to be. Or they feel weird about their hips. These are real things," he says. "When a woman goes into the dressing room with your dress on, it might be the most beautiful dress on the runway, but if it feels a little tight on the hips or she can't wear a bra with it, she's not going to spend $3,000."

The Saks shop-in-shop is certainly a first step towards building a significant direct retail business. And while e-commerce is further down the roadmap, the company's newly-relaunched website links through to online wholesale partners. (The clever setup allows the consumer visiting the site to shop and browse everything on offer at once, and also gives the Altuzarra team insight into what is resonating commercially.)

ADVERTISEMENT

But while connecting with the consumer one-to-one is a priority, Altuzarra is less convinced about delivering so-called fashion immediacy. “You can be ‘see now, buy now’ and show the most beautiful dress on a beautiful model, but if the client goes to the store and tries it on and doesn’t feel good, it’s not an incentive to buy it,” he says. “And vice-versa. I think if you show six months in advance, and she goes into the store and it fits beautifully, and it’s the right price — she’ll buy it. I don’t think it’s any more complicated than that, personally.”

It's no surprise that Altuzarra's balance of unrestricted creativity and confident pragmatism is desirable to other fashion houses: Given his partnership with Kering, rumours abounded when there were turnovers at both Gucci and Saint Laurent. Outwardly, he appeared uninterested. But to believe that Altuzarra has zero interest in taking on another role, at some point, would be naive. For now, however, he is committed to his brand, and his brand only. "One thing I really learned working with some of the designers I worked for, especially Riccardo, is the power of steadfastness and being focused on one thing," he says. "I think it's very easy in this industry to say yes to things, because plenty of people throw money and opportunities at you, and sometimes the hardest thing is to say no." It's not always easy. "Sometimes I think, 'Am I being left behind or not doing what I should be doing?'" he admits. "But you always find your centre. I certainly have never regretted anything that I haven't done. And I feel so happy about where I am."

Related Articles:

[ Turning Point | How Joseph Altuzarra Found His Signature SilhouetteOpens in new window ]

From analysis of the global fashion and beauty industries to career and personal advice, BoF’s founder and CEO, Imran Amed, will be answering your questions on Sunday, February 18, 2024 during London Fashion Week.

The State of Fashion 2024 breaks down the 10 themes that will define the industry in the year ahead.

Imran Amed reviews the most important fashion stories of the year and shares his predictions on what this means for the industry in 2024.

After three days of inspiring talks, guests closed out BoF’s gathering for big thinkers with a black tie gala followed by an intimate performance from Rita Ora — guest starring Billy Porter.