The Business of Fashion

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

NEW YORK, United States — At Proenza Schouler's Spring/Summer 2017 runway show held in the Dia:Chelsea art gallery, box-shaped seats draped with black patent leather were arranged in a Pac-Man maze. Models made sharp lefts and rights, twisting and turning their way back to the back of the house. But as precisely choreographed as the fashion show dance might be, the seating arrangement of guests attending the show is just as thought-out — if not more so.

Clusters of editors, buyers and friends of designers Jack McCollough and Lazaro Hernandez were carefully positioned around the space. In Section G, there was artist-and-brand-muse Jen Brill, sitting with the artist Dan Colen as well as Moda Operandi's Lauren Santo Domingo, who was positioned near Garage magazine's Dasha Zhukova and renaissance woman Alexa Chung. Rookie founder and actress Tavi Gevinson was mixed in there, too.

Nearby, the young blogger Colby Jordan was paired with Tiffany design director Francesca Amfitheatrof, while stylist-sisters Samantha and Vanessa Traina were holding court with landscape architect Miranda Brooks. Over in Section H, downtown scenester Ladyfag was set up with Mel Ottenberg, while model and Gucci muse Hari Nef sat alongside Pop Magazine's Stevie Dance.

Those arrangements may feel organic, but orchestrating a front row that sings — something that contributes to the energy of the show itself — requires creative thinking, cultural insight, compromise and astute knowledge of the inner workings and power hierarchies of the fashion industry.

ADVERTISEMENT

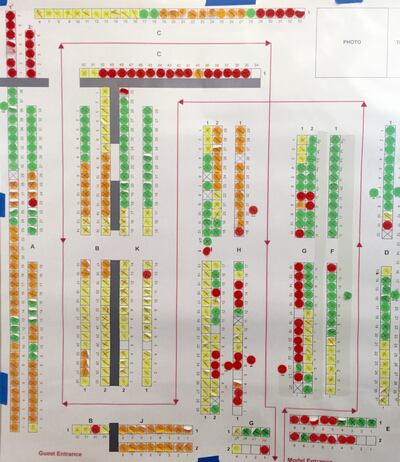

The seating chart for Proenza Schouler's show | Source: Courtesy

"Seating is the micro of the macro. Throughout time, it's gone through different transformations that reflect both the industry and the greater culture," says KCD president Ed Filipowski, whose public relations, production and strategy firm is charged with seating at Proenza Schouler, along with dozens of other shows during Fashion Month, including Givenchy, Gucci and Alexander McQueen. "Today, there's a new order in place. A new power seating that contrasts with the traditional," says Filipowski.

Twenty years ago, when runway shows were still primarily for the trade, the industry's power politics were more straightforward and, in some ways, more punishing. Editors from hyper-competitive magazines were not to be seated within each other’s sight lines. Nor could they be seated next to each other. “It was about who is looking at whom,” adds Rachna Shah, KCD’s vice president of public relations and managing director of KCD Digital.

During the era of the “ego editor,” as Filipowski calls it, the stakes were also higher. “People noticed when someone was moved from the second row to the front row. There was a political dynamic,” he says. “Competitive reviewers were seated at opposite ends of the aisle. They were like caged lions; bulls at the colosseum, waiting to come out. It was very formal. Seating really mattered to them. It was their throne and their right.”

It could also get very nasty. “I was punched in the stomach,” he laughs. “It was about perceived power. Seating reflected the editors and retailers, and less the designers.”

But the dynamics of show seating began to shift in the 1990s. It started with designers who welcomed students and fans into their shows, like Marc Jacobs, whose informal seating in the early days meant that everyone who stood in line for a seat would get one. But it was new runway show formats, pioneered by the likes of Helmut Lang, that really broke down the walls.

“[Lang] had a very cockamamie runway, with turns and corners. He really did not consider the seating from the editors or retailers’ perspective. He considered it from his own perspective, who supported him, and most importantly the energy in the room,” Filipowski explains. “He would sit there and put his mind inside the model's, consider the girl walking, what the energy was when she turned a corner, and what the energy would be when she turned another corner. He would mix people up to achieve that energy.”

Alexander McQueen's Spanish collection — his first after striking a deal with what was then called Gucci Group — was another turning point. "There were 40 front row seats. Usually, there is a minimum of 120," Filipowski recalls. "The pre-show music was the sound of a bull fight and sex. I've never seen such confused, angry people. Lee was a disrupter."

ADVERTISEMENT

As fashion merged with entertainment, celebrities replaced models on magazine covers and were compelled to wear designer dresses on the red carpet in a new form of brand marketing. They were also invited to runway shows, which forced brands and PRs to redraw their seating plans. “At first celebrities were like sheep,” Filipowski says. "They were lined up in the front row altogether, whether they knew each other or not.”

Today, this layout certainly persists at certain shows, but increasingly brands and celebrities are looking for more than a single photo opportunity and the need to create multiple media moments in a single setting changed seat charts once again.

Seating was also impacted by a new generation of designers, with different values to their predecessors. "A turning point was the rise of the new American designers," Filipowski says, citing Thakoon, Proenza Schouler and Phillip Lim in particular. "They have a genuinely different attitude about this industry. They don't buy into the power and the ego, and it's had a strong effect."

Case in point: Proenza Schouler's front row, which welcomes the requisite editors and retailers, is also filled with friends and supporters of the brand, from Vogue's Lisa Love to the film director and writer James Oakley. But like every modern show, Proenza's layout — which typically only consists of two rows — also includes digital influencers. To be sure, the rise of digital as a medium — from online publications to bloggers to Insta-girls — also significantly changed the makeup of fashion show attendees. What's more, as more local news outlets and stores reduced their travel budgets — and sometimes eliminated positions altogether — digital stars and international press began to fill theses seats, further transforming layouts.

Filipowski remembers the moment when he understood the impact digital publishing was having on the industry. It was a Gucci show in the late 2000s. "I realised that the voices in the back row were more important than the voices in the front row," he says. "I knew things were changing. It was a whole new democratic voice."

"Suddenly, the show became where people talked," Shah adds. In the past, teams of editors and buyers would discuss their opinions on collections as a group before voicing them through official channels, thereby relaying the same message. But Twitter, and then Instagram, meant that the market editor in the fourth row could instantly express her personal opinion without this kind of filter. Indeed, it sometimes changed the balance of power among editors. "It marked the demise of the ego editor," Filipowski says. "To stay young, you had to adopt. The biggest egos left." These days, friends are often seated together, as they're likely to Tweet more that way, Shah says, amplifying the all-important online conversation around today's fashion shows even further.

Of course, some things never change. KCD, for instance, still plots out its seating charts on paper, using colour-coded Avery dot labels to indicate buyers, US editors, international editors, friends and other groups. (For years, they even shipped boxes of those dots to Europe every season.) And some of the old tensions certainly still exist, although it's been quite some time since Filipowski was physically assaulted.

What certainly hasn't changed is how strongly designers care about who is invited, and where they are positioned in the venue. "The majority of designers care," Shah says. After all, in an industry full of gatekeepers where value is socially created, where people sit and what that means for the conversation around a show can affect business.

Related Articles:

From where aspirational customers are spending to Kering’s challenges and Richemont’s fashion revival, BoF’s editor-in-chief shares key takeaways from conversations with industry insiders in London, Milan and Paris.

BoF editor-at-large Tim Blanks and Imran Amed, BoF founder and editor-in-chief, look back at the key moments of fashion month, from Seán McGirr’s debut at Alexander McQueen to Chemena Kamali’s first collection for Chloé.

Anthony Vaccarello staged a surprise show to launch a collection of gorgeously languid men’s tailoring, writes Tim Blanks.

BoF’s editors pick the best shows of the Autumn/Winter 2024 season.