The Business of Fashion

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

NEW YORK, United States — Sporty & Rich made a name for itself by repurposing popular brand motifs like the Land Rover logo for its line of sweatpants and basics, the perfect fit for customers looking for Instagram-approved loungewear while stuck at home during the pandemic.

Too perfect, it turned out. The direct-to-consumer label was quickly overwhelmed by a 1,200 percent surge in online orders. Customers flooded the brand's social media accounts with complaints about shipping delays and quality issues. Founder Emily Oberg became a target as well, when screenshots of testy interactions between the 26-year-old founder and frustrated customers surfaced on Instagram.

In an email to customers, Oberg was contrite: “We started out as a small, one-person business and grew in a way we never could have anticipated. In the process, we made some huge errors and mistakes, and for that I am truly sorry,” she said.

“When my customers, the ones that have given me the privilege of doing my chosen work, are disappointed, there is no worse feeling,” Oberg said in an email to BoF. “As a founder-led business with no employees prior to April 2020, the vastness of responsibility was overwhelming. I have made mistakes. The most evident thing for me was to apologise to my community, and also to thank them for allowing me to fix my errors and grow. The act of forgiveness is an essential part of the human condition.”

ADVERTISEMENT

Sporty & Rich appears to have survived its brush with cancellation. The brand joins countless others in deploying a carefully worded apology to quell a scandal before it spirals out of control. Though the corporate apology has a long history, consumers have exposed its shallowness in 2020, as they hold brands to account for discriminatory workplaces, unethical supply chains, culturally insensitive products and more.

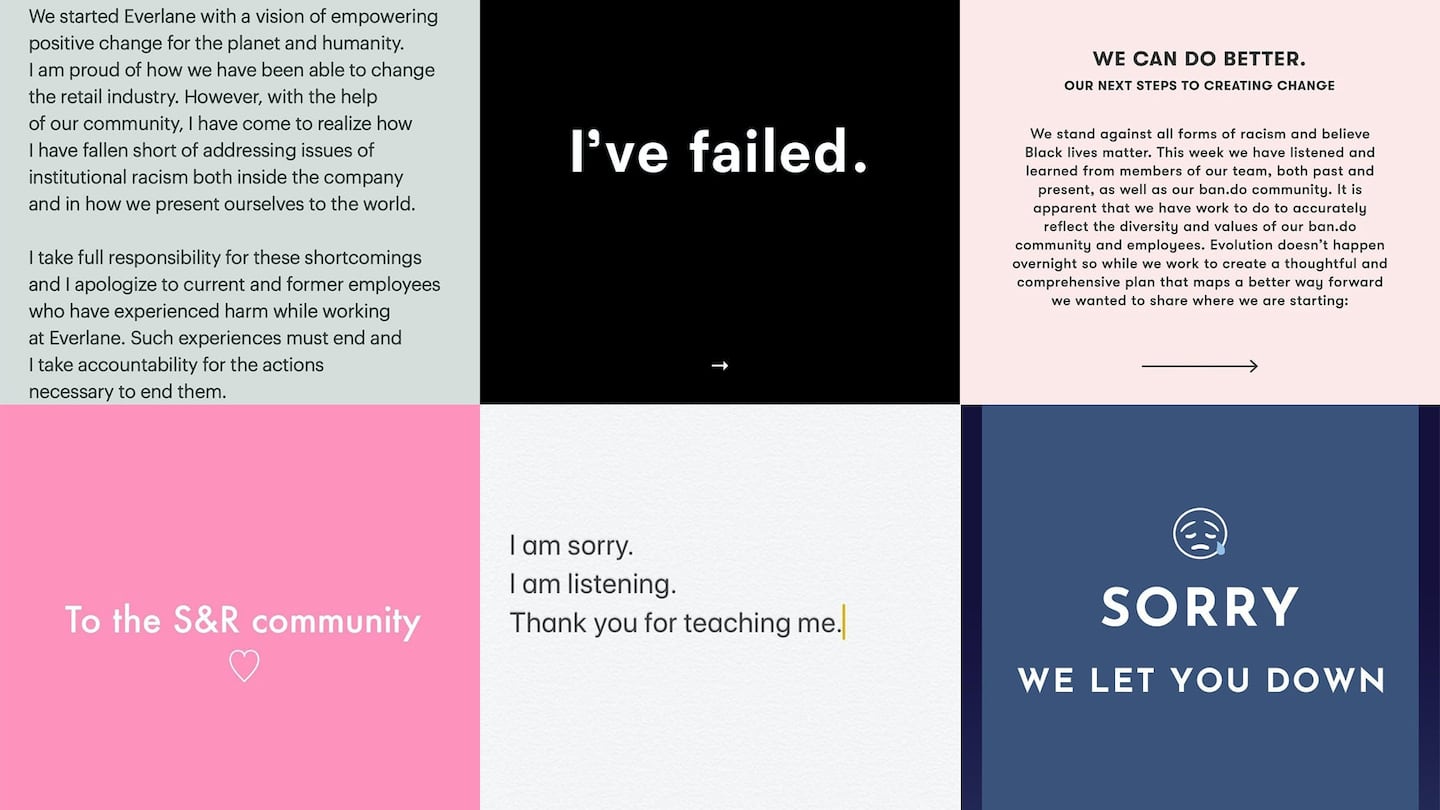

In the last month alone, the list has grown to include Everlane (two Instagram posts apologising for failure to foster an inclusive workplace and upholding institutional racism), Reformation (a six-slide Instagram carousel detailing various failings around diversity and inclusion) and Shein (also a six-slide Instagram post apologising for selling a swastika necklace), among others.

When everyone is apologising, it's like no one is apologising.

But as the number of genuine — or genuine seeming — messages grow, the public apology is in danger of losing effectiveness. Brands are finding that words are no longer enough, as consumers demand action in addition to regretful statements. Gap Inc., for example, paired its apology for ending a partnership with Telfar Clemens with a commitment to pay the designer's original fee.

“When everyone is apologising, it's like no one is apologising,” said Sarah Evans, founder of public relations agency Sevans Digital. “It becomes sort of a white noise or static noise, where everyone's doing the same thing and your brand messaging gets lost.”

To Apologise or Not to Apologise?

Fashion brands are quick to issue public apologies because they know consumers will opt to spend their money elsewhere if they aren’t quickly appeased.

“Any sector where ... switching supplier is relatively painless, these are the sectors where minor transgressions lead to grovelling apologies,” writes Sean O’Meara, co-author of The Apology Impulse: How the Business World Ruined Sorry and Why We Can’t Stop Saying It. “[Fashion brands] know how easy it is for their customers to shop elsewhere, so they practically fall over themselves to say sorry when an apology is demanded of them.”

The nature of a public apology depends on the type of offence, its scale and who the brand harmed.

ADVERTISEMENT

Corporate failures, especially in fashion, tend to fall into one of two buckets: cultural or operational, O’Meara said. An operational failure has to do with how a brand runs its business, and can often be easier to address with consumers. Adidas apologised for initially opting not to pay rent on its stores in April and reversed course.

It's far easier to apologise for what you've done than for what you are.

Cultural failures are trickier. Because consumers feel a deep attachment to “humanised” brands, especially fashion brands, cultural offences can feel like a direct insult to a group of people or an example of further exclusion outside the fashion system. What’s more, cultural failures — racist imagery in a product, for example — are often easier to understand than complicated supply chain issues.

“It's far easier to apologise for what you've done than for what you are,” O’Meara said.

That’s especially true when a segment of consumers are offended by something core to a brand’s DNA, said branding and marketing consultant Priyanka Maharaj.

In 2014, when Maharaj was Calvin Klein's global marketing director, the brand started using the hashtag #MyCalvins and encouraged customers to post photos of themselves in their underwear. Maharaj said there was some criticism of the campaign, but the brand chose to stand behind it because the hashtag, which it still uses in marketing imagery today, reflected the brand's codes.

Maharaj said brands need to ask whether the consumers who are offended represent a market segment they can afford to alienate. When Nike decided to side with Colin Kaepernick in 2018 (a decision that was reportedly hotly debated internally) after the pro football player-turned-activist kneeled during the National Anthem as a gesture against police brutality and racism, the brand actually benefited from its advertisement, despite an initial but short-lived backlash. The degree of the offence also matters — an apology is warranted if a brand causes people to lose their jobs or inflicts emotional or financial harm.

The decision to apologise is often more art than science, particularly when the transgressions are decades, or even centuries old. Chanel has not acknowledged, much less apologised for founder Gabrielle "Coco" Chanel's alleged ties to the Nazi regime in wartime France. Hugo Boss acknowledged making Nazi uniforms in 1997 and later apologised — though it took over a decade. Brooks Brothers, which was founded in 1818, has been accused of using cotton harvested by slaves in its early years. The brand said in June it was looking into its potential ties to slavery and said in a statement: "If the company benefited in any way from this oppression, we wholeheartedly apologize and we firmly state that it would be entirely contrary to our beliefs today."

When it comes to offences from the distant past, the main goal for a brand should be to show how it's evolved beyond its problematic past, said Iesha Reed, a luxury brand consultant who has worked for brands including Montblanc and Swarovski.

ADVERTISEMENT

How to Say “I’m Sorry”

Before any public statements are released, a brand should acknowledge the issue with its employees first, said Reed. An apology must be released quickly, but not before a plan is in place to correct the underlying mistakes.

“You make sure that you clean your house before people come over,” Reed said.

When crafting an apology, a brand must, “stand, walk, and talk,” said Frances Frei, a Harvard Business School professor who specialises in organisational operations and diversity and inclusion. Frei’s three-step approach means a brand must do its part to first educate itself about the problem, signal support for a cause or solidarity with the offended party, and pledge to support them in demonstrable ways to right the brand’s wrongs.

Take Reebok, a brand that didn't offer an “I’m sorry” to consumers after critics said it had benefited financially from Black culture without significantly supporting that community. In an Instagram post on June 11, the company signalled its commitment to supporting Black Lives Matter, outlined a specific plan for how it would do so in part by pledging a $15 million investment in the Black community over five years, and encouraged its followers and customers to hold the brand to account.

https://www.instagram.com/p/CBT-zVMHZmF/

O’Meara recommends that brands centre the victim in the apology rather than the brand.

“‘We fell short of our high standard,’ or ‘we let our community down,’ a lot of these bad apologies are very self regarding,” he said.

Brands should prioritise the message rather than how it looks. Holding up an apology so it can fit aesthetically into a corporate social media feed can be self-defeating.

Moving Beyond Words

Throughout the month of June, several brands committed lump sum donations to organisations including the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and Black Lives Matter as part of their apologies to consumers for instances of racism.

“Brands need to make financial sacrifices that benefit the people harmed by the original indiscretion,” said Chris Roan, a marketing strategy and growth consultant. “As much as marketing and branding is about emotional connection, at the end of the day, these companies play commercial roles in our society, and their apologies should (usually) include commercial recompense.”

Brands need to make financial sacrifices that benefit the people harmed by the original indiscretion

Maharaj said that while donations can be powerful, there are other ways an organisation can signal a commitment to cultural change within a brand, including encouraging employees to take paid service days alongside executives to volunteer towards a cause.

“There are so many things like that that companies can do that is different from making one large donation, which is the easy way out from a PR perspective,” Maharaj said. “There are so many more authentic ways to actually show that you care and show your employees and consumers that it is something that really matters to you.”

Related Articles:

[ Now’s the Time for Brand Founders to Speak Up. Here’s How.Opens in new window ]

[ As Brands Rush to Speak Out, Many Statements Ring HollowOpens in new window ]

[ Is Facebook Too Big for Fashion Brands to Boycott?Opens in new window ]

Often left out of the picture in a youth-obsessed industry, selling to Gen-X and Baby Boomer shoppers is more important than ever as their economic power grows.

This month, BoF Careers provides essential sector insights to help PR & communications professionals decode fashion’s creative landscape.

The brand’s scaled-back Revolve Festival points to a new direction in its signature influencer marketing approach.

Brands selling synthetic stones should make their provenance clear in marketing, according to the UK’s Advertising Standards Authority.