The Business of Fashion

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

LONDON, United Kingdom — As far as insults go, it doesn't get much worse than this. "You, hypocrite."

The word cuts deeper and stings longer than even the sharpest of obscenities. Questioning someone’s integrity is a serious business and to be labelled a hypocrite suggests a quiet but profound sort of contempt that no person — and certainly no profit-seeking brand — wishes to hear. The awkward irony surrounding the notion of hypocrisy, however, is that the more passionate and vocal you are about a cause or injustice, the more exposed you are to be called "the H-word" in the first place.

Pioneers like Stella McCartney, Vivienne Westwood and Katharine Hamnett know this all too well. Having helped shape our understanding of what it means to be a "designer with a purpose," they have endured the wrath of the sanctimonious few for years. By aligning their namesake fashion brands with the kind of earnest evangelism and rowdy social activism that they undertake, these businesswomen have become easy targets. Vitriolic mudslingers find them irresistible.

In McCartney’s case, accusations tend to come from detractors in the fur lobby who conveniently find hypocrisy in moves such as her decision to partner with Adidas, a brand that doesn’t ban animal leather. National treasure status doesn’t immunise Vivienne Westwood from censure either. In Britain, a variety of critics deem her eco-warrior credentials flimsy or bogus, and the most scathing among them often champion the same causes she does. Even the grand dame of the "fashion with a conscience" movement herself, Katharine Hamnett, has had the H-word levelled against her from time to time.

ADVERTISEMENT

"It's unfair but you do end up inviting more scrutiny on yourself when you stand up for a cause, especially in this industry," says industry veteran Diane Pernet, a contemporary of Hamnett, who also led her own fashion brand through the 1980s.

Without losing sight of the bigger picture — that a designer like Stella McCartney boasts legions of loyal customers emboldened by her stance on important issues and ringing endorsements from the likes of the United Nations and COP 24 sustainability convention — it can still be hard to endure the tyranny of a cynical minority. “Try putting yourself in her shoes,” Pernet urges.

Brands have always stood for something. What's now being actively played out is the ability of brands to stand against something.

As a brand trying to do some good while turning a profit, your head might tell you to pay no heed to the critical voices amplified by online echo chambers. But your heart would soon remind you that being labelled the H-word still hurts, even if it doesn’t bruise the bottom line. Either way, why put yourself on the moral high ground in the first place when you could be making money without all the grief?

"Brands have always stood for something. What's now being actively played out is the ability of brands to stand against something," says Rebecca Robins, Interbrand's global chief learning and culture officer.

“Many brands are still learning how to be true to themselves while being true to a call to action,” she adds, although the hardest thing of all is for brands to “manage the expectations of their [consumers], fans and followers around that call to action.”

‘That’s a Catwalk, Not a Soapbox’

Historically, when fashion brands wore their principles on their sleeves, it was seldom a good look. In the same way that parents advise teenagers to never talk about politics or religion at a party, brands were warned to steer clear of serious issues because their efforts often rang hollow. The polite version of a common refrain heard at the time went something like this: "That’s a catwalk you’re on, darling, not a soapbox, so get off your high horse."

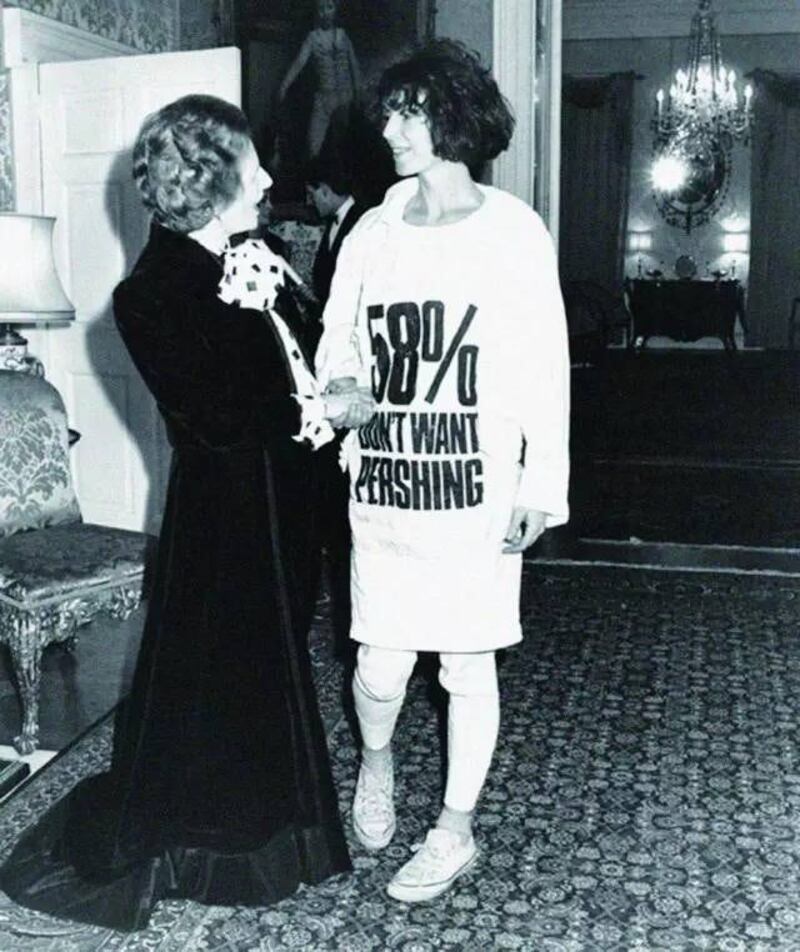

Katharine Hamnett, in a T-shirt with a nuclear missile protest message, meeting Margaret Thatcher in 1984 | Source: Courtesy

ADVERTISEMENT

“To be honest, you can understand why. Katharine [Hamnett] and Vivienne [Westwood] were the real deal, but just about everybody else put their foot in their mouth because they’d speak up about issues they were totally clueless about or they did it in a totally superficial way,” says Pernet. “You know the type, phony fashion people pretending to be do-gooders while behaving like monsters backstage. It really was a recipe for disaster.”

“I mean, now it’s becoming a ‘cool to be kind’ culture — but what you have to remember is that back then fashion was still very much ‘cool to be cruel’,” she adds, reflectively.

In 1984, when Hamnett wore a T-shirt with a nuclear missile protest message to a reception at 10 Downing Street hosted by then prime minister Margaret Thatcher, she was regarded by many of her industry peers as a troublemaker or an attention-seeker. Twenty years later, attitudes hadn’t changed much. Stella McCartney says she was “blatantly ridiculed” for her vegetarian approach to fashion in the noughties. And as recent as 2015, prominent members of the fashion establishment once again rolled their eyes at Vivienne Westwood when she flamboyantly drove a military tank through the winding lanes of Oxfordshire to former prime minister David Cameron’s home in a protest against fracking.

“Let me tell you why these aren’t publicity stunts. It’s because they’ve been persistent and they’ve been consistent too,” says Pernet. “I mean, look, they’ve always stuck to their guns even when it was bad for business.”

"Besides, do you really think we'd be where we are now with Gucci supporting gun control and all these huge brands getting political all of a sudden, without designers like them paving the way?"

Importantly, the early efforts made by these and other mavericks laid the groundwork for a new kind of consumer culture, later fortified by the past decade’s ethical fashion movement. Today, some 50 percent of consumers worldwide say they would switch, avoid or boycott brands based on their stance on controversial issues.

Now it's becoming a 'cool to be kind' culture — but what you have to remember is that back then fashion was still very much 'cool to be cruel.

This sentiment intensifies among younger demographics like millennials and Gen Zs, and in markets like the US. According to a 2017 Cone Communications survey, 87 percent of American consumers stated they would purchase a product based on values or because the company advocated for an issue they cared about.

"I'd say the pivotal point for this might be the 2016 #GrabYourWallet campaign led by Shannon Coulter and Sue Atencio," Syl Tang, journalist and author of "Disrobed," tells BoF. "Their efforts were so widely covered in the media and affected sales of [Ivanka] Trump products…that it was truly impossible to ignore," says Tang, referring to the impact of a boycott on sales of Trump's brand at department stores like Nordstrom and Neiman Marcus.

ADVERTISEMENT

However, Tang, a futurist, cautions that a significant minority of US consumers do not want brands to take on an activist role. For some, the idea of brands getting involved in political and social issues is an uncomfortable one and, for others, it is as outrageous as a dystopian future where corporations step into the role of the morality police.

The Vexed and Vocal Minority

“Some consumers definitely don't [want this]. They follow the libertarian model of ‘leave your politics out of my clothes, out my kitchen, out my goods, out my life’. But I think the numbers speak for themselves,” says Tang.

Colin Kaepernick for Nike | Source: Facebook

For big brands, getting behind a cause can be a double-edged sword. “In Nike’s September earnings briefing, North American sales climbed 6 percent during the quarter [and] this was after the Kaepernick campaign,” Tang adds, citing the controversial decision by Nike to feature Colin Kaepernick, the face of the NFL’s "anthem protests" and a Black Lives Matter supporter in their 2018 "Just Do It" campaign.

In the now iconic ad, the NFL athlete — who famously kneeled rather than stood during the American national anthem to not "show pride in a flag for a country that oppresses black people and people of colour" — says, "believe in something, even if it means sacrificing everything." In the backlash that ensued, some disgruntled consumers posted videos on social media of burning Nike shoes and cutting the Nike swoosh off their clothes.

One outspoken sports broadcaster felt so affronted by Nike’s move that he wrote a book called "Republicans Buy Sneakers Too." “Evidently, I have an antiquated notion: I think every American company should try to serve every consumer regardless of that person's race, gender, ethnicity, religion, sexuality or political persuasion,” wrote Clay Travis in an op-ed to plug the book, "I don't want to have to place every company into Republican or Democratic buckets, and decide what to buy while analysing these factors.”

Although Travis claims that his book is selling well, he might have attracted more readers and earned a more sympathetic response from the opposition had he not printed a gilded message on the book cover proclaiming, "Banned from CNN & ESPN" as if it were a badge of honour.

After posting a video on Youtube where he reiterated his prior commitment to “buy other brands like Under Armour, Reebok, Adidas for my boys and myself,” one of his followers summed up the mood among that community: “I won’t be buying any more Nike and all my friends either [sic]. Nike sold out to the SJW’s [social justice warriors].”

Such views may be part of a vocal minority in the US, but there are some global markets where the majority are either sceptical or opposed to linking brands to sensitive issues, albeit for very different reasons. In markets like China, Russia and the Middle East, for example, it could be problematic — or in some cases dangerous or illegal — for brands to take a stand.

Brand activism takes a beating from other quarters too. Mark Ritson, the columnist for Marketing Week famed for his take-no-prisoners approach, has more than a few choice words for his fellow marketers.

“This is brand purpose, the current concept du jour of every trendy, helium-filled marketer in the country,” Ritson moans, calling his colleagues “well-meaning numpties” before explaining that, “a sure sign of how fleeting and pathetic most of this thinking is can be taken from the binary, bipolar nature of the concepts that occupy marketers.”

For Ritson, it is the lack of nuance and the speed with which brands are jumping on the bandwagon that irritates him most. “There are companies that have used brand purpose to great effect. I’d put Unilever at the very top of that very shortlist,” he concedes, but the general “state of decay” of corporate ethics and big business “is mirrored in many of these ‘purpose-driven’ brands and their absolute hypocrisy.”

There was a time when wading into political issues was an absolute taboo, but today it's starting to become detrimental to a brand's bottom line if they don't take a stand.

Rattling off a litany of alleged offenders that includes Starbucks, Google, Lush and Cadbury, Ritson is anything but shy. “It’s a smokescreen and we all know it,” he grumbles.

Be that what it may, but the number of consumers in many Western markets expecting fashion brands to make commitments has now reached a critical mass. Tang, for one, believes there is no turning back the tide. “There’s now peer pressure to actually have an opinion and to wear that opinion,” she says.

No More Room for Apathy

Quynh Mai, founder of Moving Image and Content, a New York-based digital marketing agency that counts H&M and Sephora among its clients, couldn’t agree more. “There was a time when wading into political issues was an absolute taboo, but today it’s starting to become detrimental to a brand’s bottom line if they don’t take a stand,” she says.

Mai draws a comparison between brands breaking this taboo and the growing number of celebrities doing the same by “publicly and loudly” declaring their social and political views.

With Hollywood A-listers like Amy Schumer willing to get arrested for the #MeToo movement in protests over US Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh and Rihanna declining to perform at the Super Bowl halftime show in support of aforementioned Kaepernick, the stakes are getting higher. Mai believes that celebrity interventions like these are now "making it harder and harder" for brands to stay mute on similarly controversial topics.

"As people lose faith in government, they feel like they have no voice, so they turn to other people, like celebrities, influencers and also to brands as bellwethers of culture and values," says Mai.

“In the States in particular, they feel frustrated, disenfranchised and powerless against a failing political system…but they’ve learned they can wield some power through two ways: their pocketbook and their voice on social media.”

Corporate neutrality is completely finished.

“As brands become more human-like, they’ll have opportunities to deepen relationships with consumers beyond product. The upside to leveraging that deeper connection is to earn loyalty and insight, the downside is the risk of being more vocal about moral and political issues.”

What has taken some by surprise is the kind of brand that is now wading into these issues.

Last year, when outdoor clothing company Patagonia announced it was planning to sue the Trump administration over the US president’s attempt to reduce protected land and published a message on its website stating that "The President Stole Your Land,” it was an unprecedented move that did raise a few eyebrows, but Patagonia’s ‘hardcore’ environmental stance is well known and well documented.

Gucci, on the other hand, is a brand few would associate with hot-button issues like gun control, until the Italian luxury brand donated $500,000 to the March For Our Lives demonstration. Wading into a highly-charged American political issue would have been unthinkable until the arrival of the tag team that is chief executive Marco Bizzarri and creative director Alessandro Michele, who pivoted the Gucci brand in a bold new direction.

With two of the company’s employees being among those shot at Florida's Pulse nightclub in June 2016, Gucci’s first-hand experience with the tragic impact of gun violence will have certainly fed into Bizzarri’s decision to take up the cause, but there are broader dynamics at play too. “Corporate neutrality is completely finished,” he recently told BoF.

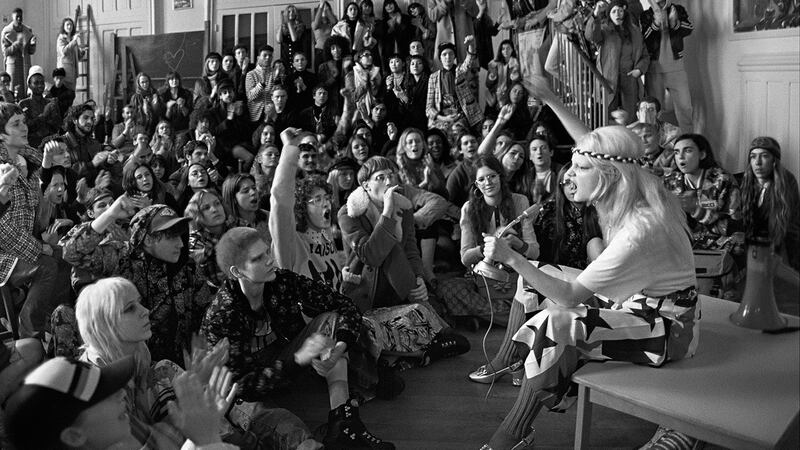

Gucci's protest-inspired pre-fall 2018 campaign | Source: Courtesy

Bizzarri is not the only leader of a time-honoured luxury house who can feel the earth begin to move beneath his feet. This new activist landscape is one where heritage players must consider making all kinds of new brand allegiances. "Fashion cannot lock itself in the so-called ivory tower any more. We need to be conscious of the [wider] world and reflect what's happening," says Balenciaga chief executive Cédric Charbit.

The marketing theory underpinning this is that brands have to reflect the community and culture they serve, their values and beliefs included. So as consumers themselves become advocates, brands have to follow suit to align with them.

“Aligning with your customer’s values creates an emotional pact that goes beyond the moment. Emotional connection drives loyalty, but also, and most importantly, advocacy — even if it’s just a tagged post of the brand on Instagram,” Mai explains. “In the years ahead, I predict that it will be difficult, if not impossible, for brands to stay apolitical.”

Watch Out For #Wokewashing

If Mai’s prediction is accurate, it foreshadows new challenges and dilemmas for brands going forward. Since most big social and political issues are interrelated, taking a stance on one can have implications on another, making the brand a lightning rod for opinions of all kinds.

A case in point is the ripple effect of Nike’s Kaepernick endorsement. After the initial controversy, an aftershock enveloped Nike that revolved around the apparent discord between the brand’s allyship with Kaepernick and the low wages that living wage campaigners say the company pays its workers abroad — many of whom are people of colour in Southeast Asia.

When BoF contacted Nike about this reaction, the brand declined to comment, but in the past spokespersons have maintained that all of its factories are required to pay at least the local minimum wage or the prevailing wage.

A no-nonsense corporate social responsibility executive might be inclined to defend Nike on this matter, asserting that such criticism conflates two unrelated issues. That, however would miss the point. For some consumers, Nike’s progressive stance on Kaepernick’s activism is nevertheless undermined by its apparent failings on the other side of the globe. Think of it as reputational cross-contamination, they would argue.

In the years ahead, I predict that it will be difficult, if not impossible, for brands to stay apolitical.

Civil rights activist and Black Lives Matter supporter DeRay Mckesson takes a slightly more nuanced view. Days after Nike released the advert starring Kaepernick, Mckesson was invited to appear on MSNBC news for comment.

“Nike standing behind [Kaepernick] in this moment and in this context is significant, [and] I think it’s more good than bad,” he said. “But this doesn’t absolve Nike from any complaints that people have about their labour practices.”

This brings us back to the dreaded H-word. Even when brands don’t face accusations of outright hypocrisy, they can face subtler criticism around how sincere their actions are or how transparent their messaging seems. It is a phenomenon that Tang has christened, with characteristic dry wit, the “spectrum of genuineness.”

“There are those who are genuine and those who are cashing in, but there are also the brands who want to be part of the conversation, but don't necessarily know how to, and can sometimes hit an unintentionally tone-deaf moment,” she says.

Pepsi's now infamous TV advert starring Kendall Jenner — as an impromptu protestor who defuses a heated demo by giving riot police a can of cola — is arguably one of the best examples of this. It points perfectly to the latest way that netizens are calling out brands online. Just when the men and women of the corporate boardroom got to grips with the business implications of being #woke, social media gave birth to its cynical cousin: #wokewashing.

A portmanteau of getting woke and whitewashing, wokewashing describes what a company does when it feigns to have principles of social justice but is in fact being opportunistic in a way that can be proven by inconsistencies in the brand’s position on similar issues. The word isn’t quite trending — yet — but it is already powerful and poignant enough that the boffins at Oxford Dictionaries have taken note of it on their blog.

Maria Grazia Chiuri's first Dior collection debuted for Spring/Summer 2017 | Source: InDigital

For some, Karl Lagerfeld's mock feminist rally for his Chanel spring/summer 2015 runway show — complete with "I'm Every Woman" blaring from the speakers — sits somewhere on the sliding scale between wokewashing and parody. For others, it is Maria Grazia Chiuri's attempt to co-opt feminism into Dior through T-shirts emblazoned with "We Should All Be Feminists."

Fashion critic Robin Givhan summed up the latter argument when she wrote that "Chiuri uses feminism as an overlay or a gloss," reducing it to "slogans and a backdrop."

“It’s not necessarily hypocritical. But I’m sure the way these designers interpret the brand activism movement is probably much more palatable to some of their clients with deep-pockets [than] it would be if they got involved supporting issues more deeply,” says Pernet, who mischievously describes this sort of approach as a form of “diet activism” that is fitting for an industry like fashion, which she believes will continue to “cling on to its old ways for a while yet.”

Hamnett, who spent her entire 40-year career selling politically-charged slogan T-shirts, laments many of the “watered-down” messages of today.

Although she didn’t cite any specific brand, she has said that recent examples from the luxury industry are “a bit namby-pamby,” because the messages sit on the fence of important issues rather than drawing a clear line in the sand. This is, of course, their intention. Many fashion brands are still being deliberately vague or supporting universally popular causes to avoid controversy.

Consistency But at What Cost?

"Let me say this, if I worked for a brand or a business that didn't have the legacy [of making social commitments] that we have at Levi's, then I would be concerned about coming across as wokewashing, as you call it, as superficial and not authentic," says chief marketing officer of global brands at Levi Strauss & Co., Jennifer Sey.

“It has to be real. It has to be fully embedded in the way you run your business. It can’t just be an ad campaign. You’d definitely be called out for that [but] we’re not just jumping on the bandwagon.” says Sey, citing LGBTQ equality and gun violence prevention as two of several causes the company champions. “There certainly are issues that we don’t wade into, but I think we’re pretty consistent about those we do.”

Before Levi’s became involved in the battle for gay marriage in the US — filing one amicus curiae legal briefing after another in state and federal supreme courts — it had already offered same sex partner benefits to its own employees as early as 1992.

“This might not be so much of a hot-button issue now, but it certainly wasn’t always like this. We were the first Fortune 500 company to do so, because a lot of our employees were LGBTQ back in the 90s, and still are today, so we felt it was the right thing to do,” she contends.

It has to be real. It has to be fully embedded in the way you run your business. It can't just be an ad campaign.

While the decision was unquestionably a bold one for the times, Sey admits that the brand didn’t need to make any major sacrifices to implement what was an internal policy, nor did it cause the brand to suffer reputational damage. One issue that did, however, was when Levi’s pulled its financial support from the Boy Scouts of America when the organisation banned gay troop leaders.

“That did have a significant short-term impact on our business. People were angry,” she recalls. “But we thought it was the right thing to do back then and if we wanted to be consistent on this issue, [then] that was something we needed to do.”

According to Sey, brands gain credibility by demonstrating both consistency and sincerity for their activism. The challenge with following this model, however, is that it compels global brands like Levi’s, which sells in over 110 extremely diverse countries, to make some very difficult choices.

Brands either risk serious repercussions by faithfully aligning themselves with a controversial cause across all international markets — in spite of the various cultural, legal, religious and social objections — or they make some compromises to address these realities, but face the scrutiny of their most passionate consumer advocates back in their home markets.

In other words, the predicament these brands face can be summarised as one where “they are damned if they do; damned if they don’t,” Pernet observes.

Doesn’t this paradox worry executives like Sey, who is responsible for the messaging of a company with nearly $5 billion in annual revenue at stake?

“Yes, of course it does. But we’ve been clear that if we stand by it, we stand by it.”

A good example of this is Levi's Pride campaign and pro-LGBTQ stance. "We know that in some of our markets it is not even legal to be gay, but we still run these campaigns there anyway [and] we believe it's therefore even more important to support the LGBTQ communities there."

“Certainly we were concerned [about launching it in Russia where there is a so-called ‘gay propaganda law’] and we do our due diligence, but our bigger concern is not being consistent in our values. We recognise that if we’re not consistent in our stance then that’s hypocritical,” she adds.

Sey’s caveat to her claim of a consistent approach on such issues across all markets is that “there are a whole host of reasons that one market may or may not run a particular campaign or prioritise one over another,” but she maintains that the Levi’s Pride campaign, for one, “has been extended across the globe. It’s in China; it’s in Russia; it’s in countries where it’s still very controversial and potentially illegal.”

Solidarity to the Extreme

In an increasingly polarised world where social media amplifies and accelerates real world tensions, the threshold for outrage appears to be getting lower. At the same time, when the cause of that outrage is connected to perceived hypocrisy, the number of people who immediately react by shaming a brand or calling for a boycott seems to be getting higher. What exacerbates this phenomenon is that a divisive issue on one continent can now ricochet across the world to another in record speed.

Such was the case when Paris Jackson, who identifies as bisexual, was labelled "hypocritical" in an op-ed by Gay Star News' entertainment editor because she appeared on the September 2018 issue of Harper's Bazaar Singapore. The reason cited was that Singapore still criminalises homosexuality. The storm it created was so intense that Jackson felt compelled to publicly apologise.

As fashion brands venture into activism, they need to be prepared for immediate online vitriol and backlash. They need to have a plan in place and a 'war room' mentality to respond to the community in real time.

No sign of regret a month earlier when Nicki Minaj was criticised after appearing on the August cover of Harper’s Bazaar Russia. Jonathan Van Ness, an American television personality from Queer Eye, took to Twitter suggesting it was wrong for a queer ally like Minaj to collaborate with a fashion magazine in Russia because it was somehow complicit in Russia’s so-called gay propaganda law.

“This is classic American entitlement,” contends Pernet. “Talk about double standards. These kinds of overreactions are counterproductive. Are we supposed to boycott every brand or magazine in every country where the laws aren’t progressive enough yet?”

“It sounds to me like they’re trying to tar the whole country of Russia with the brush of its government,” she goes on. “Using that logic, all Americans and the whole American fashion media would be tainted by Trump’s crazy politics. Nobody expects people to boycott American brands because of his policies.”

Paris Jackson and Nicki Minaj's controversial covers | Source: Courtesy

Other supporters of LGBTQ equality were quick to distance themselves from Van Ness’ view but some doubled down in their support. Whatever your views on examples like this, they clearly demonstrate that the complexity that brands face when confronting such issues is getting harder to navigate.

Most telling of all, though, is that this specific episode left Russians of all persuasions scratching their heads. "Russian readers never took it that way," explains Daria Veledeeva, the Moscow-based editor in chief of Harper's Bazaar Russia, who commissioned the Nicki Minaj cover. "I was so surprised with this feedback, because I was thinking that actually the cover with a famous supporter of LGBT rights all over the world, putting her on the cover of a Russian magazine, would make the opposite statement. To me, it was [intended as] a positive thing."

One of Russia’s staunchest advocates finds such cases perplexing too. Mikhail Tumasov, chairman of the Russian LGBT Network, says that while he appreciates VanNess’ passion, he finds it “a little bit strange to have this criticism” for putting her on a magazine cover.

“I would say that to me it’s very flat to see her as only an LGBT supporter, she’s also a rapper; a role model; a star. We’re not just one face; we have a lot of faces [and] we have a lot of identities,” Tumasov adds.

It’s a Minefield Out There

The same could be argued about brands. No fashion brand is a monolith. Just as the number of touchpoints and channels that connect a brand to its consumers continues to grow, so too does the number of pillars needed to uphold a brand’s increasingly expansive set of values. This offers the potential to develop a richer, more well-rounded brand identity but it also inevitably means more room for conflict, contradiction and hostility.

“As fashion brands venture into activism, they need to be prepared for immediate online vitriol and backlash. They need to have a plan in place and a ‘war room’ mentality to respond to the community in real time. The alignment on the cause needs to be at the very top and the messaging cannot waver,” cautions Mai.

“It’s important in these moments for the founder or CEO to step forward and send a clear and simple message that’s delivered sincerely and often, swiftly. They need to put their name and face in the public to show their sincerity and should not hide behind a press release that comes from ‘a spokesperson.’”

When there is vigorous debate in a community about the brand’s alignment with a cause, having outside counsel is also wise. Mai suggests that brands should invest in social listening to determine what the community is saying online and at what scale and, if the debate turns ugly, to have an expert on the subject or a crisis management expert ready to lead or at least offer sound and objective advice.

At Levi’s, external experts are key. Sey says that the longstanding relationships with NGOs that her team has nurtured represent the full spectrum of causes that the brand supports. “You don’t want to wade into any of these issues without consulting with one of these experts to make sure you’re looking at the issue from all sides [and] avoid communicating it in a way that’s not complete,” she says.

I think we're over-indexing on whether brands care. [Often], they are pushed into it.

As more brands take on an activist mission and get deeper into purpose-led activities, industry leaders are beginning to ask more practical questions like where the function should sit in the organisation and who is ultimately responsible.

“For us it’s a real partnership between brand PR, brand marketing and corporate communications — which is stronger than ever now [because of it] — and of course our CEO is involved as is our chief legal counsel,” Sey says. “It hasn’t required additional resources for us [but] I can imagine companies where that might not be the case. It does require broadened capabilities [among our staff though].”

A small but growing number of marketers and professional service firms now recommend that purpose gets a dedicated role in the C-suite. While it is still very early days for the fashion industry, the "chief purpose officer" is a new role that is being slowly rolled out and tested in sectors as diverse as pharmaceuticals, FMCG, agribusiness and entertainment.

In a few firms, it is more about focusing internal culture and strategy around the company’s core business purpose. Others focus on wider, external purpose and how the company can affect positive social change or better the world. The latest management thinking among some experts is that aligning these two interpretations of brand purpose under the umbrella of a single leader can significantly boost company performance.

According to Mai, however, building values into a brand culture and market position takes alignment across all departments and should always include product. “Although brands might appoint a point person or a task force to execute on these ideas, [all] aspects of the organisation must be aligned,” she says.

“[You have to ask the whole team], are you willing to stand by this cause, because it is ingrained in who you are, despite any backlash? If so, then move forward.”

Playing the Devil’s Advocate

For those working in the fashion industry who find the whole notion of brands “getting woke” awkward or pushing a politically-charged social agenda unappealing — and no doubt there are more than a few out there — it is worth pausing to ask whether this movement really is for everyone. The temptation, as ever, is to find a one-size-fits-all solution even when brands of varying complexions require very different prescriptions.

Sceptics like Ritson are unequivocal about their position. “Despite attempts by many to force the purpose agenda on all brands and all marketers in every target segment, it represents an occasionally vital, often irrelevant, usually oversold approach to brand positioning,” he wrote in a particularly stinging edition of his column in Marketing Week.

“Do customers want purpose-filled brands? Sometimes. In some categories. Depending on how it is done. A lot of the time they don’t give a fuck. And usually most segments will not pay more for the purpose-filled privilege even if they are theoretically in favour of it.”

His is a point of view that is not entirely alien to futurists like Tang, who believes the potency of purpose-led marketing depends on how sticky a customer is to the brand. “If the brand is well-differentiated, already sticky, then there won't be much movement either direction. However, if there is an alternative and that alternative is equally convenient, then it is a risk,” she warns.

"I think we're over-indexing on whether brands care. [Often], they are pushed into it," she continues. "And I don't think brands influence belief as much as make people feel better about their purchases. In other words, I want to buy a diamond but I'd rather it not be a conflict diamond. [Or] if suddenly Apple does something controversial, I don't see huge droves quitting their iPhones, but with Nike, it's sneakers and that is not as sticky."

“For consumers, it comes down to, ‘can I take it or leave it?’ It’s important not to discount the inertia of how hard it is to change. And change is harder to make than people think. If it were easy, brands wouldn't hire someone like me,” she quips.

We're not perfect, but we're always <em>striving</em> to do the right thing. I think that has a strong impact on the way that the message is received.

Nevertheless, whether brands set themselves up to be on the right side of history or not, is a matter that they can’t afford not to take seriously. Some purists will never be satisfied with the idea of mixing a brand’s inherently capitalist mission with the ideals of social justice. You can almost hear the cries of "champagne socialism." Worse still, they contend, is encouraging fashion brands — with all the baggage that comes with that industry — to pontificate through hashtag activism. Indeed, for these and other critics, hypocrisy will continue to be the indictment they use most readily in this growing movement.

Ultimately, however, fashion brands must each respond to this movement in their own way because it is gaining speed, impacting more of the market and, most important of all, it is shaping the lens through which growing numbers of consumers weigh up their purchasing decision. If it is not an unstoppable force, then it is at least one that will probably be with us for a long time.

Taking a stand on big issues to maintain brand integrity while earning back some of the eroding value of brand equity is not easy — and it is not for everyone. But for some brands, it clearly is the future and therefore a critical factor of their future success.

"Our discussions internally [are always], 'do we have a right to participate in this issue?' We [then look] at it outside-in and every which way in between. The way we've always tried to position our participation in any of these issues is that, we're not perfect, but we're always striving to do the right thing. I think that has a strong impact on the way that the message is received," offers Sey of Levi's.

“Look, we aren’t standing up here saying that you won’t find fault in any of our actions over the past 150 some odd years [of Levi’s] but…we are moving in the right direction. [In the end], I think it’s about doing better than you did yesterday.”

From analysis of the global fashion and beauty industries to career and personal advice, BoF’s founder and CEO, Imran Amed, will be answering your questions on Sunday, February 18, 2024 during London Fashion Week.

The State of Fashion 2024 breaks down the 10 themes that will define the industry in the year ahead.

Imran Amed reviews the most important fashion stories of the year and shares his predictions on what this means for the industry in 2024.

After three days of inspiring talks, guests closed out BoF’s gathering for big thinkers with a black tie gala followed by an intimate performance from Rita Ora — guest starring Billy Porter.