The Business of Fashion

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

BEAVERTON, United States — It was the last few days of the 2014 World Cup, being held in Brazil, and as I made my way through airports on three different continents for an interview with the chief executive of Nike, football was front of mind. All along my journey people had gathered around television screens, eager to see who would claim the world's biggest sports prize: Germany or Argentina.

But another battle was also being played out for the hearts and minds (and wallets) of football fans everywhere — this one between Nike and its arch-rival Adidas. While the 2014 FIFA World Cup was officially sponsored by Adidas, as were the teams of both Germany and Argentina, in the months and weeks preceding the final, it was Nike that seemed to have the upper hand. With high-profile launches for its new Magista and Mercurial Superfly boots; the blockbuster success of a digital video entitled “The Last Game” featuring animated avatars of star players like Cristiano Ronaldo, Wayne Rooney and Neymar Júnior; and fifty three percent of the players in the World Cup brandishing Nike footwear, the American sports giant was flexing its growing muscle in football. In the fiscal year ended May 2014, Nike football sales were up 21 percent to $2.3 billion out of total revenues of $27.8 billion.

Nike’s design and innovation ethos is rooted in enabling star athletes. But its business is built upon a sophisticated global marketing machine selling aspiration and empowerment to large swathes of mass consumers around the world, linked to the fundamental belief that, “If you have a body, you are an athlete.”

Indeed, looking down at the feet of fellow passengers along my journey, I spotted the Nike swoosh on an Indian grandmother wearing a traditional salwar kameez on the plane from Mumbai, a hipster waiting with her mother in the immigration queue at Heathrow, and a toddler at Chicago’s O’Hare airport taking his very first steps.

ADVERTISEMENT

At the helm of this huge global corporation is Mark Parker, the designer turned chief executive who first started at the company in 1979. Today, Parker appears to be as comfortable meeting with investors on Wall Street as he is hanging out with street artists and contemporary design legends, a 'right-brain, left-brain' balance that is core to his success and to Nike's ability to innovate and execute at scale.

BoF sat down with Parker in his office — a suite brimming with eclectic design objects, art collectibles and personal mementos — at the heart of the sprawling Nike campus just outside Portland, Oregon, to decode the company’s operating model.

BoF: It’s not all that common to have someone with a design background running a massive global corporation. How has this informed the way you manage Nike as a business?

MP: One of Nike’s co-founders, Bill Bowerman, had a great influence on me. He was a sort of mad scientist: an obsessive, compulsive, eccentric inventor. He would cobble up shoes using whatever he had at his disposal. When I came to Nike, I started as a designer. I was a runner and I would modify my shoes to try to make them better, so the fit with Nike was very natural. I’ve carried that through all the many different roles that I’ve had. I’ve probably spent more time on the creative side here, but I’ve always been one of those creative people who is very comfortable in dealing with the other side: the business side, the operational side. And I saw the power of Nike; the potential of Nike was, ‘How do you get those two worlds to connect?’

Deep in the creative world there’s almost this built-in “us and them” mentality. But I could also see the need to have some discipline around what we’re doing to operate a business, particularly at scale, and to edit and make choices and to exercise discipline. I’m always reminded of the Frank Gehry quote, “The greatest source of creativity is a timeline and a budget.” I think there’s some truth to that.

BoF: How did this thinking influence the way you shaped the organisation when you became CEO in 2006?

MP: For me, it was always about trying to strengthen the things that made Nike successful and then change the things I thought we would need to change to be a modern, relevant, compelling brand — and a successful business. One of the biggest challenges we have is to make choices. There’s so much opportunity everywhere you turn, so you have to make choices and then you go hard at the things that you decide are really important. Coming into the CEO role, that became even more clear: the need to make choices. Not just choices about what we do or what we don’t do, but what we do and how we accelerate that, how we catalyse creativity around an opportunity.

One of the things I’ve been pushing is the collaborations, the connections with outside people to accelerate the incredible talent we have internally. We have amazing talent within this company, but I think our potential is based on how well we manage that talent and then invite new ideas and creativity and points of view into what we do. I love that.

ADVERTISEMENT

BoF: Can you give me an example?

MP: Oh there are so many. We do it in terms of product, processes, materials, manufacturing, digital... the athletes of course, they’ve always been our main muse and our focus in terms of collaboration. But one that I really like a lot, and maybe it’s dated now, but I still like it a lot, is our work with Marc Newson on the Zvezdochka shoe [named after a Russian dog sent into space in 1961]. We both had a mutual fascination with the space program.

This seemed to be something that the astronauts in the space station might actually use. The whole process of working with Marc was actually really enjoyable. I think the potential of our company is based on the ability to connect and collaborate with smart people in really specific areas.

Mark Parker's office space | Photo: Jeff Dey for BoF

BoF: The voice of design exists across the business at Nike, but it's not just about designing for the sake of aesthetics, it's also about designing with specific problems in mind.

MP: Yes, and from that a unique aesthetic will come. Some of the most interesting designs, from a visual and aesthetic standpoint, are from a very functionally-driven kind of approach. That’s always been kind of what’s driven us from a design standpoint since the very beginning.

Not to harp on Bill [Bowerman], but he couldn’t care less what the shoe looked like. He had no concern whatsoever, as long as it helped his athlete perform better. Now, we care what the shoes look like, what the product looks like, what the apparel looks like — but it’s driven from a desire to help the athlete perform better and reach their potential.

BoF: In the fashion world people often talk about haute couture as the laboratory for ideas and for dreams. Is this dialogue you have with high- performance athletes kind of the same thing?

ADVERTISEMENT

MP: I think that’s a very accurate way to express it. We do a lot of work specifically with athletes and out of that process comes a product that is quite unique: an item. That has very strong influence beyond that one item. We have set up design in a way that there’s a large part of the creative process here that is incredibly organic. It’s not briefed. Marketing’s not at the door waiting. It’s a very organic process of a designer working with an athlete and just taking all the influences around them to create something really interesting. That experimentation and everything else is fair game in that process.

BoF: Can you think of something you did with an athlete that was specifically focused on the individual but translated to something bigger and more widely distributed?

MP: We had Neymar who was here before the World Cup and he saw this gold shoe. This was a shoe that Michael Johnson wore in the Olympics in Sydney where he set a world record and won the gold medal. Neymar saw it and was like, “Oh my gosh what’s that?” I told him and he said, “That was a big influence on me. When I was a kid I used to spray paint my football boots gold!”

That’s one of the things I try to do: get people to open up their peripheral vision a little bit and see what’s going on — whether it’s in basketball, whether it’s in running — and to share those ideas, those solutions. Sometimes it’s an aesthetic or a material or a cushioning system; look at how you might interpret that in a different category, with a different athlete.

The amount of creative innovation — or the real functional innovation that we do here — is enormous and the power of Nike is our ability to leverage that across a diverse set of sports and athletes and at scale.

The visual analogy for me is the sound mixer board and it’s always about trying to get that right sound and balance. It’s never-ending. During the course of a song it’s going to change many times over and that’s what I feel like in my roles.

BoF: Yes, innovation is a word that you hear over and over at Nike. How does innovation work here?

MP: It’s hard to explain that in a simple answer. It’s not just the product that has to resonate; it’s also where it’s coming from. The brand needs to mean something. That’s part of the product as well. This is probably the most valuable thing that we own, so there’s a lot of care and feeding and nurturing that goes into the brand itself. And, then, of course, the product has to be there too. It’s the combination of those things.

Colour, for example, is really interesting. I think there was a bit of a breakthrough in colour at the London Olympics when all the athletes wore the bright citron colour that is very recognisable.

And that colour wasn’t just a colour; it was actually related to something that was meaningful. Therefore it had a bit of authenticity and for some people it had a bit of personal empowerment if they put that on and they felt differently: stronger, bolder, more confident, more expressive.

BoF: It was interesting to see the idea of a bold pair of sneakers creeping into mainstream fashion too.

MP: Yes, how you may have somebody who’s completely dressed in black but they’ve got a splash of colour on their feet. Fashion is not a four-letter word around here. We embrace that. We don’t strive to create for fashion’s sake, but the fact that what we do becomes fashionable for whatever reasons I think is great.

BoF: Nike’s ability to remain innovative and disruptive is really impressive, but how do you do this at scale? The bigger you get, the more you risk getting taken over by process.

MP: Yes, yes. Well, first of all, the antenna is up all the time. For me personally and I think for all of us in the company, the process never becomes the end. People don’t care about process. They care about what comes out. You know, what’s the result of the work that you’re doing?

These aren’t just sports that have different functional needs, they’re cultures. If you look at basketball, it’s a culture. If you look at football, it’s a culture. I mean, running — it’s a culture. Even golf. They’re all very different. The athletes all have very specific needs. It’s ultimately how relevant are you? The answer to that is: how connected are you to the culture? Are you bringing something within you to the party or are you just coming in with a “me too” type of product or experience?

It used to be that the different functions were sitting in different parts of the company. With category neighbourhoods, all the functions that are working on the category are now sitting together.

BoF: A culture of innovation and design also requires risk-taking. I wanted to talk about this in the context of your Digital Sport division, including the Nike Fuelband, which has been a focus for Nike, but also hit some bumps in the road.

MP: We’ve felt for a long time that bringing the digital experience to the consumer in a form that allows them to learn more about themselves, to be a part of the community, to create a deeper, richer experience — that’s really important and it’s going to be more and more of an expectation.

There’s a lot of technological developments here, but the real potential comes with the connection we have with different partners. When we put the Fuelband out, there weren’t a lot of devices in the marketplace, maybe two or three to speak of. I think the way things are moving now, you’ll see a plethora of devices coming out and the ability to capture data is going to be embedded in many, many things.

We still intend to be a part of that, but through partnerships and collaborations. Our goal is to reach as many people as possible in the work we do. It’s probably going to be more software-based than it has been with the hardware. I don’t think our core competency is developing devices; there are others that do that well and will do that at a higher level. Some of the things that are in the works right now, I think, are incredibly compelling. We want to be a part of that. Those are all important parts of Nike achieving greater scale, from tens of millions of users to hundreds of millions of users, multiple platforms, multiple devices, multiple partners.

BoF: Circling right back to the beginning of our conversation, for all those designers out there, what advice would you give to them on interaction with the business side?

MP: Try to avoid that feeling that it’s an ‘us and them’ world. I do think that the power of design is amplified when it learns how to connect with the business side in a way that actually enables design to be executed at the highest level. Now that doesn’t always happen. There are many situations where business might not be an enabler; it might be a detractor; it might be a hurdle. But the more that design can appreciate the power of combining creativity with the power of scaling a business, it will only empower design in the end. It will only help design achieve even more. It’s convenient here at Nike because we’ve always embraced design, so it’s easy for me to say and easy for us to embrace that. At many companies, that may not be the case.

I do think that there is something about balance. There are times when we need to let the design, the creative, the innovative side just power through and [business] gets out of the way. Other times we need to bring that back in. The visual analogy for me is the sound mixer board and it’s always about trying to get that right sound and balance. It’s never-ending. During the course of a song it’s going to change many times over and that’s what I feel like in my roles. I’m a choreographer, trying to achieve that right mix. I actually really love that. I love pushing back here and pushing forward there. For us, it’s very natural.

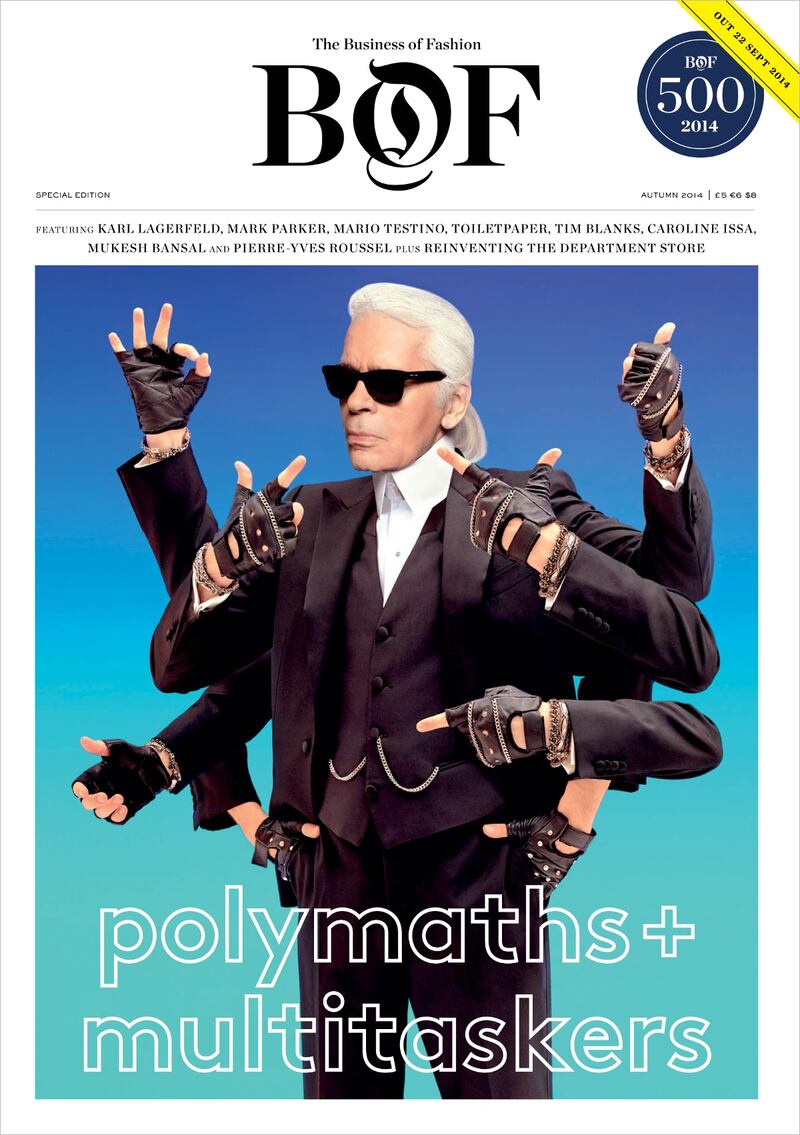

This article originally appeared in the second annual #BoF500 print edition, 'Polymaths & Multitaskers.' For a full list of stockists or to order copies for delivery anywhere in the world visit shop.businessoffashion.com.

Cover of the BoF 500 ‘Polymaths & Multitaskers’ Special Print Edition

From analysis of the global fashion and beauty industries to career and personal advice, BoF’s founder and CEO, Imran Amed, will be answering your questions on Sunday, February 18, 2024 during London Fashion Week.

The State of Fashion 2024 breaks down the 10 themes that will define the industry in the year ahead.

Imran Amed reviews the most important fashion stories of the year and shares his predictions on what this means for the industry in 2024.

After three days of inspiring talks, guests closed out BoF’s gathering for big thinkers with a black tie gala followed by an intimate performance from Rita Ora — guest starring Billy Porter.