The Business of Fashion

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

NEW YORK, United States — It's the Monday after the 89th Annual Academy Awards and Mark Shapiro is standing in the corner of a conference room in IMG's New York office, recounting the previous evening's events on the phone with a colleague. The topic of discussion was not the snafu to end all snafus — "La La Land," "Moonlight," Best Picture... you remember — but instead the identity of Naomie Harris' stylist.

"Was she one of ours?" Shapiro asks with eagerness. He wants to know if Harris was dressed by someone on the roster of the Wall Group, the artist management agency that was acquired by entertainment conglomerate WME-IMG in July 2015 and represents stylists, makeup artists, hair stylists and manicurists. It was surely a bit of a letdown for Shapiro to learn that stylist Nola Singer, daughter of famous Hollywood lawyer Marty Singer, is taken care of elsewhere. After all, he described the white-sequined, mullet-hem Calvin Klein dress, designed by Raf Simons, as "awesome," as if he was recounting a slide into third base at a baseball game.

Not surprising, perhaps, given his fist-clenching jock background. Shapiro, who was hired as IMG’s chief content officer in 2014 and promoted to co-president of WME-IMG in November 2016, isn’t a fashion native. He came up in sports — rising the ranks at ESPN — then swerved into another lane, joining Six Flags Amusement Parks as chief executive and finally landing at Dick Clark Productions in 2010, where he ran the show until Guggenheim Partners acquired the company two years later. If this loose trajectory has a common theme, it’s recreation. Shapiro is in the business of making sure his customers have a good time, whether that’s at a professional bull riding competition — in 2015 IMG acquired Professional Bull Riders Inc., a bull riding circuit headquartered in Colorado — on a roller coaster or at a runway show.

The runway show has proven to be the most challenging. “Fashion is steeped in heritage and the way things were always done. The industry is reticent to change,” Shapiro says. “And you can’t fight change.”

ADVERTISEMENT

Fashion-as-entertainment is nothing new. Clothes have long served as a prop — literally and figuratively — for amplifying other domains of popular culture. Costume designers, from Edith Head to Colleen Atwood, tell stories through clothes, while television programming like CNN’s “Style With Elsa Klensch”, MTV’s “House of Style” and the Weinstein Company’s “Project Runway” have long turned fashion into a spectacle. But while those series made an indelible mark on the fashion industry — and the niche of people aspiring to join it — only “Project Runway,” which relied more on the thrill of reality show-style competition than the fashion itself, managed to break through to the masses.

The right mix of accessible product and entertainment content could be explosive for fashion.

But much has changed since Project Runway’s first season aired back in 2004. Today fashion is increasingly the main event. Consider that Calvin Klein dress worn by Harris. As the Best Supporting Actress nominee hit the red carpet, Marie Claire creative director Nina Garcia, who co-hosted US television network ABC’s Oscar red-carpet special, discussed Simons’ still-nascent tenure at the American fashion house as if it was a detail the pre-show’s 20.9 million viewers would actually care to know.

The next morning, in the most fortuitous of outcomes, Simons debuted his first Calvin Klein men's underwear campaign, starring all four of Best Picture-winning Moonlight's male stars, three of whom wore Calvin Klein during the awards. Mahershala Ali, Alex Hibbert, Ashton Sanders and Trevante Rhodes were captured in black-and-white by photographer Willy Vanderperre and styled by Olivier Rizzo, wrapping up the brand's red-carpet-to-advertising strategy in true cinematic fashion.

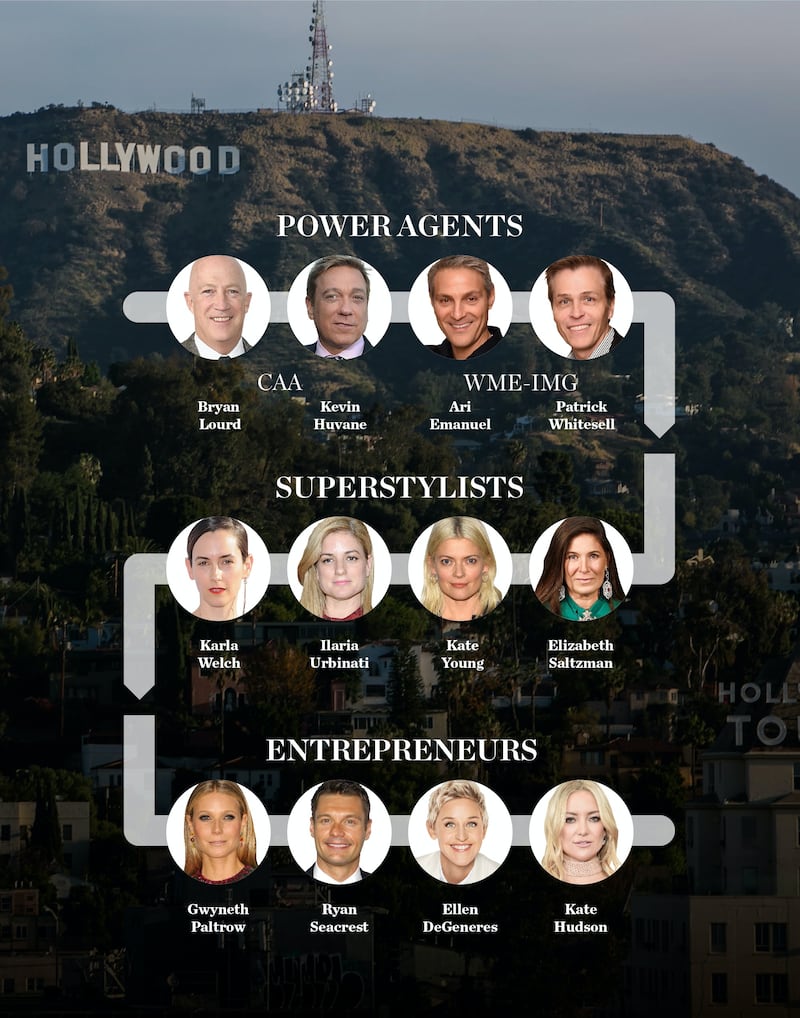

The string of events helps to illustrate why Shapiro's bosses at WME-IMG — co-chief executives Ari Emanuel and Patrick Whitesell — as well as their competitors, including Bryan Lourd and Kevin Huvane at Creative Artists Agency (CAA) and Great Bowery's Matthew Moneypenny, are making a big bet on fashion's potential as a cultural entertainment industry to rival sports, music and film.

In May 2014, global entertainment agency WME closed the deal to buy IMG — best known for representing models and sports stars — for $2.4 billion. IMG already owned Art + Commerce — acquired in 2007 for an undisclosed amount — offering access to top photographers including Craig McDean, Steven Meisel and Vanderperre and fashion stylists including Marie-Amélie Sauvé and Brana Wolf.

In 2015, WME-IMG — which is now majority-owned by Silicon Valley private equity firm Silver Lake Partners — bought the Wall Group, whose roster of celebrity stylists and makeup artists helped to further fuel the red-carpet marketing machine. Around the same time, it made a play for MADE Fashion Week, the independent entity set up at Milk Studios that had quickly redefined the parameters of the official New York Fashion Week — already owned by WME-IMG — in a matter of a few short years.

Further acquisitions are certainly not out of the question: perhaps a public relations firm — or two — or a monetisation entity such as affiliate marketing firm RewardStyle, or an “influencer” agency that represents Instagram and YouTube stars. There are also seed projects within the WME-IMG organisation, including an agency representing up-and-coming photographers and other artists called Lens, as well as Made to Measure (M2M), a fashion video network populated with content that’s both original and acquired, from the famous Isaac Mizrahi documentary “Unzipped” to “Tea at the Beatrice,” a series hosted by the recently passed, highly influential Glenn O’Brien, who recruited his industry friends to be interviewed.

“It was about getting our original content in the game right away,” says Susan Hootstein, M2M’s executive producer and creative director.

ADVERTISEMENT

Around the same time, fashion industry insider and former Trunk Archive chief executive Matthew Moneypenny formed his own powerhouse, with 12 businesses that include Streeters, Bernstein & Andriulli, M.A.P, Camilla Lowther Management and a collective roster that boasts major fashion stars, from Grace Coddington to Juergen Teller. "The people who make this media and make this content and tell these stories in a fashion and beauty context clearly have opportunities beyond their traditional milieu," Moneypenny said in a 2016 interview with BoF. And although Moneypenny exited the company in May 2017 after disagreements with its investors, Great Bowery remains intact...for now.

Creative Artists Agency, WME-IMG's fiercest competitor, has plenty of skin in the fashion game, too. While its fashion-specific division was rolled into its licensing group in 2013, it continues to represent fashion clients, including Tom Ford, Thom Browne and Riccardo Tisci. Its more traditional Hollywood talent, including Sarah Jessica Parker, Reese Witherspoon and Kate Hudson, are building fashion businesses.

In the past, fashion was a mirror of society and a mirror of change, now it's an active part of it.

“Fashion may end up being the most powerful in an experiential way because you wear it on the outside,” says Christian Carino, a commercial endorsements agent at CAA. “It makes you feel something when you put it on... and makes the people who see you feel something... and ultimately, makes you feel something seeing people who see you feeling something. It’s emotion in a bottle.”

But the business of fashion, unlike those other pillars of popular culture, has shopping at its core. While participating in sports, music and film may have required purchasing event tickets or consuming advertising in exchange for free content, participation in fashion requires consumers to buy clothes and accessories (as well as magazines). "Film, sports, music: they were more accessible to everybody," says Stefano Tonchi, editor-in-chief of W magazine. "You can be a spectator, you didn't need to shop."

And yet, the right mix of accessible product and entertainment content could be explosive for fashion. In recent years, as industries from sports to music to film have sought to diversify their revenue streams, the lines between consuming entertainment content and buying fashion product have blurred. Consider the Elder Statesman's $1,620 crewneck cashmere sweaters intarsiaed with NBA team logos — the ultimate in sports paraphernalia — which is part of a much wider NBA product strategy. (Global retail sales of sports-licensed merchandise generated $24.89 billion in revenue and $1.4 billion in royalties in 2015, according to the International Licensing Industry Merchandisers' Association.) Concert "merch," from Kanye's "Life of Pablo" line to Justin Bieber and Rihanna's extensive offerings, has, along with tickets, helped to supplant lagging recorded music sales.

“Today, you cannot distinguish TV from film from art, they kind of collapse on the screen of your phone somewhere,” Tonchi adds. “In the past, fashion was a mirror of society and a mirror of change, now it’s an active part of it. Now, fashion creates its own pop icons.”

Musicians, as mentioned, have come to rely almost entirely on concert ticket sales to fuel their business, as piracy and shrinking revenue from digital downloads have made making money from actual songs increasingly difficult. (While an increase in sales of recorded music over the past two years — up 8.1 percent to $3.4 billion in the first half of 2016 — indicates a shift in the other direction, whether or not those numbers will ever be as big as they once were remains highly unlikely.)

Actors and other entertainment industry creatives, too, are building their businesses beyond celluloid.

ADVERTISEMENT

The motivation is clear. With movie attendance and box office sales both in decline, the days of $40 million paydays are all but over. Instead, actors, directors and other front-of-the-house talent are looking for ways to brand themselves, starting with paid product endorsements and leading to product development, with projects as wide ranging as Martin Scorsese directing a Chanel commercial and David O. Russell making a short film for Prada to Gwyneth Paltrow and Reese Witherspoon building venture capital-backed businesses around their personal brands.

“We used to compartmentalise [actors]. You either did movies or did TV. Nowadays, actors can do it all,” says Eric Kranzler, founder of Talent Agency Management 360, who represents A-listers including Rooney Mara and Kirsten Dunst. While neither actresses are currently fronting advertising campaigns, their red carpet personas have helped to shape public perception. (Mara, for instance, became closely associated with Givenchy during Riccardo Tisci’s reign. “Whatever medium you do it in, if you’re in a creative process, then why not? They’re all just creators creating content, whether it’s television, fashion, an oil painting. Whatever it is, good work is good work.”

Fashion designers have begun to explore new opportunities, too. Tom Ford directs feature films that garner Oscar nominations. Rodarte designers Kate and Laura Mulleavy, whose first film, "Woodshock," stars Kirsten Dunst and will be distributed by the hot independent studio A24 in the autumn, are represented by WME-IMG, as is Moschino creative director Jeremy Scott. "We're trying to get the fashion industry to realise it's all cross-cutter these days," Shapiro says. "And we're just trying to take some of the stiffness out of what is a very traditional industry. [Fashion brands] were the last ones to social media, the last ones to make what is a mega marketing event — the runway show — consumer friendly."

At the same time, fashion houses have elevated red carpet dressing to a major ingredient in their marketing strategies. The painstakingly choreographed dance of a luxury house anointing a studio’s it-actress a muse, who will then don its wares both on the red carpet and in advertising campaigns — and occasionally collaborate on a short film or even a line of products — can certainly help sell a film, an actress, a garment or a perfume. But it’s also helped turn fashion into viable entertainment content in the eyes of both industry insiders and end consumers, giving rise to spectacles like Tommy Hilfiger’s ready-for-television catwalk shows, the first of which generated 2.2 billion media impressions. (Not bad for a one-night event, especially when considering that 2016’s seven game NBA Finals generated a total 5.2 billion impressions across social media and 800 million video views.)

Fashion is popular culture in the truest sense, why is it not represented that way?

CAA’s Carino, who represents Lady Gaga, cites her collaboration with Tom Ford on the designer’s Spring 2016 collection video as an example of fashion as entertainment. “Lady Gaga with Tom Ford is a music video to anyone who doesn’t know Tom Ford,” he says. “And you have no idea whether Gaga is a music artist or the leading futurist of fashion. And it just doesn’t matter.”

Fashion industry trade organisations — most notably, the Council of Fashion Designers of America and the British Fashion Council — have also tried to make their annual awards shows as watchable as any televised sports or Hollywood event, but neither has managed to secure a partner to air the proceedings on television. And while fashion has been satirised with considerable success in mainstream film and television — think “Devil Wears Prada” and “Zoolander” — the industry may finally get its due in the third season of auteur Ryan Murphy’s “American Crime Story” series, which will document the 1997 assassination of Gianni Versace and stars Penelope Cruz as his sister Donatella. Yet the hurdles to genuine fashion-entertainment are many.

“Fashion is popular culture in the truest sense,” notes Arianne Phillips, the Oscar-winning costume designer who has zigzagged between the fashion editorial, film and music worlds, working with Tom Ford on both “Nocturnal Animals” and “A Single Man,” Madonna on her touring wardrobes and photographer Steven Klein on Italian Vogue shoots. “Why is it not represented that way? My intuitive reaction is that fashion is about commerce, advertising and products, which isn’t maybe as esteemed or respectable.”

So is fashion really ready for its prime time moment? The ringmasters of American entertainment are certainly betting on it. But while the synapses are forming steadily, there are still several disconnects blocking fashion entertainment from reaching its full potential. Transforming the runway show into a consumer-facing event worth the eyeballs, let alone the price of a ticket, has proved challenging for anyone with a budget that falls below Hilfiger’s. After all, his biannual presentations now boast their very own amusement park rides. When it nets out, there have really not been any blockbuster examples of genuine fashion performances, save for the Victoria’s Secret fashion show. And many would not consider that fashion.

What comes next remains unclear. WME-IMG has experimented with bringing runway shows to malls via virtual reality constructs, and Great Bowery has had success branding its talents beyond the typical channels, such as Coddington’s fragrance with Comme des Garçons. Edward Enninful, the incoming editor-in-chief of British Vogue (and a client of Art + Commerce), collaborated with Beats. Sauvé, another Art + Commerce client, recently launched her own magazine, Mastermind, capitalising on her cult following among fashion obsessives. “Before, these artists weren’t really known to the outside public,” says Art + Commerce co-president Nadine Javier Shah. “Now, our artists are promoting themselves through social media and building their fan bases.”

Hootstein, whose M2M content was first distributed only on Apple TV, has worked to find unorthodox channels of distribution, including getting into the pre-film reel at Spotlight Cinema Networks’ 230 screens across 40 theatres in 30 cities in the US.

For the summer, she has even cut a deal to stream M2M content onto the televisions built into the gas pumps in East Hampton and other similar areas, where the target audience — affluent, cultured consumers — will be filling up.

But while there are inventive, inspired strategies moving forward every day, the thing that may be holding fashion back is fashion itself. In an industry that is, more than anything, about control, Shapiro argues that too few brands are willing to truly let go, which makes his job all that more difficult.

“There is so much pushback, hesitation. So much of, ‘I don’t want to be first,’ ‘Let someone else be the guinea pig’,” he says, fielding paper notes from an assistant asking to wrap up the meeting so that he can make it to the next. But he just has too much to say. “Content is being pushed out all over the place. There are no boundaries. Get into the pool. It’s warm.”

Related Articles

Building Great Bowery, Fashion's Super-Agency

From analysis of the global fashion and beauty industries to career and personal advice, BoF’s founder and CEO, Imran Amed, will be answering your questions on Sunday, February 18, 2024 during London Fashion Week.

The State of Fashion 2024 breaks down the 10 themes that will define the industry in the year ahead.

Imran Amed reviews the most important fashion stories of the year and shares his predictions on what this means for the industry in 2024.

After three days of inspiring talks, guests closed out BoF’s gathering for big thinkers with a black tie gala followed by an intimate performance from Rita Ora — guest starring Billy Porter.