The Business of Fashion

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

LONDON, United Kingdom — In the corner of Detective Sergeant Kevin Ives' central London office are cardboard boxes full of fakes; lookalike Nike trainers, Michael Kors handbags and Ugg sheepskin boots. The haul is just a tiny fraction of the global market in counterfeit goods — worth over $450 billion, according to the OECD — that Ives' 14-strong specialised police unit is dedicated to slowing.

Counterfeit goods constitute one of the biggest threats to the global fashion industry, stealing sales and diluting hard-fought brand reputations. The UK’s Police Intellectual Property Crime Unit (PIPCU), the only one of its kind in the world, is primarily focused on tackling the supply-side of the market, especially the organised crime gangs who drive and profit from the trade.

Established just over three years ago, PIPCU raids basements for fake goods and can put offenders in jail for up to 10 years, but just as fashion sales have moved online, so too have the counterfeiters. Under “Operation Ashiko” the unit are increasingly focused on closing down rogue websites masquerading as genuine fashion vendors.

Websites purporting to sell real Burberry, Longchamp, Prada, Gucci, Tiffany & Co, Abercrombie & Fitch and Ugg, alongside sportswear brands including Adidas, Nike and Reebok, have all been shuttered by PIPCU, according to the UK government's Intellectual Property Office, which funds the unit. Detective Sergeant Ives reports that over half the sites they close are selling footwear, from poorly made replica trainers to $1,000 faux luxury stilettos. Ranked by volume of websites, fake clothing comes second, followed by those offering faux handbags, accessories, jewellery and watches. Fashion, in other words, is the unit's main focus.

ADVERTISEMENT

“The clothing is high-end. There is no point copying the high street brands because you can’t charge anything,” explains Ives in his office in London’s historic Guildhall. “Everyone wants to have a £500 coat though, especially if you see it for £70 or £80,” he said. According to Ives, the “vast majority” of shoppers who purchase counterfeit fashion don’t actually know they are buying fakes and believe they are getting the genuine item cheaply.

“Tens of thousands of brands are being impacted,” continues Ives. “For the larger counterfeiters, the really big ones, if we can disrupt their supply chain, then we can have a real impact.”

A PIPCU investigation typically starts when a brand or trade group supplies the police with a statement outlining alleged fraud. The unit then track down the website, collect evidence and approach the UK domain name registry Nominet to have it closed. The registration details linked to one rogue website often lead to more. Thus far, PIPCU investigations have led to the shuttering of 19,000 fake websites. The unit’s success has sparked conversations with law enforcement teams from across Asia and Europe, who are considering launching similar police divisions, Ives says.

Counterfeit is a very good business for organised criminals and they take advantage of the smallest carelessness.

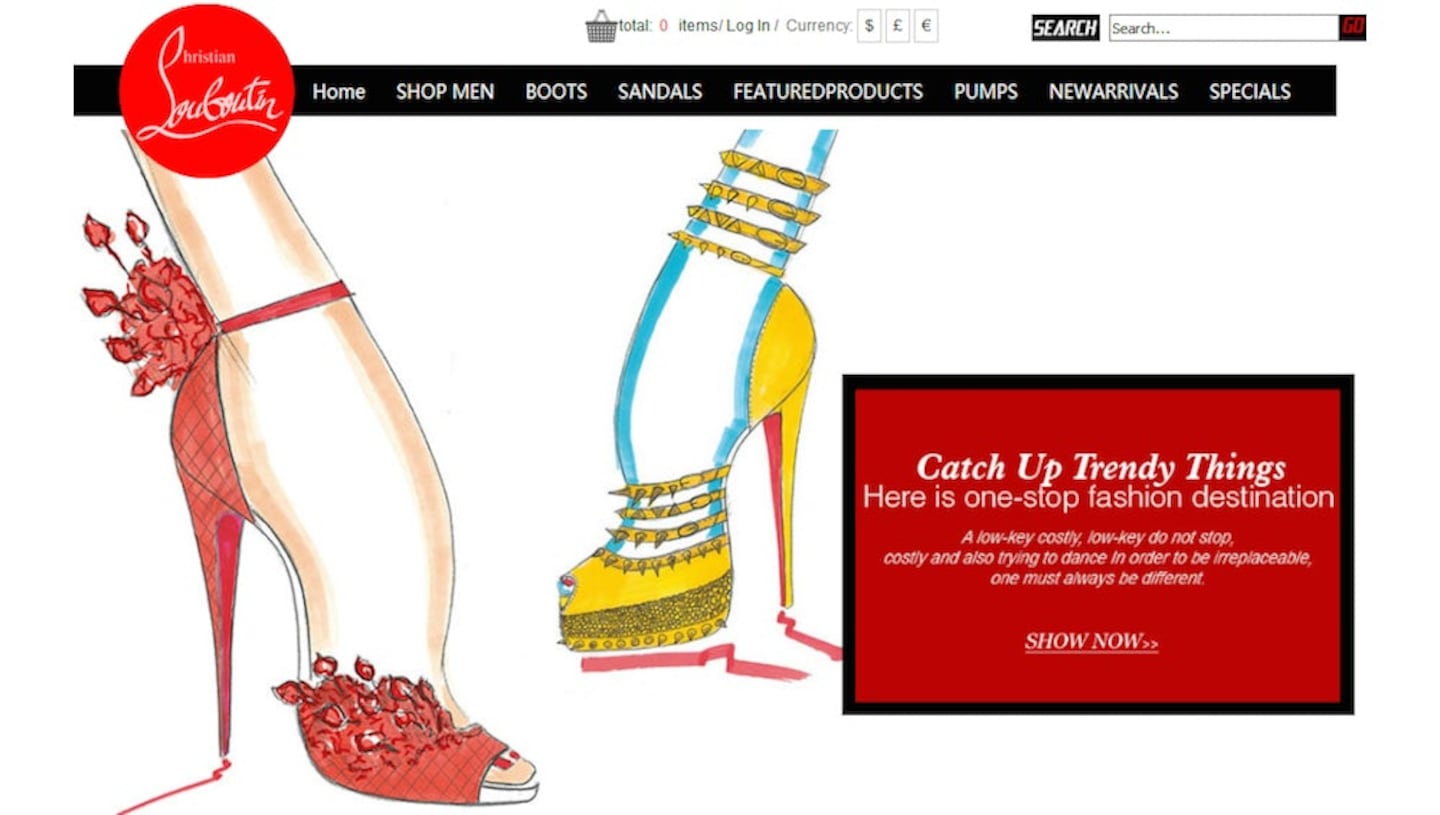

Recent site closures include those selling fake Christian Louboutin pumps, Vivienne Westwood jewellery, Mulberry leather wallets and Pandora bracelet charms. The sites are filled with stolen brand imagery and logos, alongside heavy discounts and suggestions of "outlet" or "last-season stock." But those who buy will be lucky if anything turns up, says Ives. And products that do, he warns, are vastly inferior to the genuine items.

There is no doubt fashion’s counterfeiting problem is colossal. In the European Union alone, the clothing, footwear and accessories industry loses approximately €26.3 billion euros (about $27.7 billion) of revenue annually from counterfeit goods, according to official EU statistics. That’s equivalent to nearly 10 percent of total sales. Globally, imports of counterfeit and pirated goods are worth nearly half a trillion dollars a year, according to the OECD, with US, Italian and French brands the hardest hit.

Counterfeit goods are so prolific that some luxury brands have even begun making ironic references to fakes on the catwalk. Alessandro Michele's Spring/Summer 2017 collection for Gucci featured the brand name emblazoned in large letters on a basic white cotton jersey t-shirt. Dolce & Gabbana also showed white t-shirts stamped with "D&G" and "I was there" in reference to the replicas typically sold at Italian tourist sites, while a white tanktop features a purposely-misspelt "Dolce & Gabbaba" on the chest.

The Anti-Counterfeiting Group, a UK-based trade body whose members include Burberry, Michael Kors, Hermès and Jimmy Choo, says intellectual property crime is funding other crimes like the smuggling of drugs, guns and people. Director general Alison Statham says the government needs to focus more on preventing the sale of counterfeit goods. Last year, it worked with customs and border officials to find more than 80,000 counterfeit items, with a total street value of £3.5 million (about $4.3 million), though this represents a tiny fraction of the overall trade in fakes in the UK.

One advocate of PIPCU's work is Ugg, the Californian maker of sheepskin boots, who works with law enforcement globally to carry out raids, suspend websites and initiate prosecutions, according to brand protection manager Alistair Campbell. Globally, the company has taken legal action against 60,000 websites selling replica footwear and clothing, Campbell says. "We take counterfeit prevention and education very seriously. Our approach is twofold; first, stopping the counterfeit goods from penetrating the market and, secondly, educating our consumers on how to spot a fake." Their site has a URL checker for consumers to confirm their website is an authorised retailer, as well as images of real and counterfeit bags, boxes, heels, sole stitching and security labels.

ADVERTISEMENT

Still for the fashion industry, fake websites are only one part of the problem. Today, fakes abound on online auction sites like eBay and Taobao and shopping sites like Amazon, often promoted via social media platforms. Indeed Alibaba, which owns Taobao, was placed back onto the US government's blacklist of "notorious markets" for selling fakes in December. It has sought to quell concern by making it easier for brands to request counterfeit goods be removed and has publicly announced that the company is suing two sellers of fake Swarovski watches on its platform in China.

Thomas Sabo, whose silver charm bracelets are often replicated by counterfeiters, uses a range of methods, including brand protection firms such as GlobalEyez, to search for fake listing on Taobao and other Chinese marketplaces. “Most of our customers don’t want to buy copies but they are cheated by rogue websites and don’t even know that they buy counterfeit directly from China,” says Jon Crossick, the company’s managing director for the UK and Ireland. “Counterfeit is a very good business for organised criminals and they take advantage of the smallest carelessness,” he adds. The brand monitors a range of shopping platforms and alerts operators about fake items. It also works with Google to make sure fake sites don’t come up in search results for brands, Crossick says.

Brand protection firms like Incopro, who clients include Richemont, and Markmonitor, who works for Belstaff and others, leverage technology to thwart the larger-scale counterfeiters, seeking out repeat offenders who advertise on Facebook, sell on eBay and operating rogue websites.

“The problem with the Internet is it’s all about volume,” says Charlie Abrahams, senior vice president at Markmonitor. "There might be 10,000 websites but only five individuals out there doing it. We go after the high value targets, the criminal enterprises who are very focused on this,” says Abrahams. "Brands know they won’t cure the problem but if they make themselves a hard enough target, counterfeiters will stop spending money making their products and try elsewhere.” Within the brand protection part of Markmonitor’s business, “the luxury sector has seen far and away the most growth in the last three years,” adds Abrahams.

Legal action is another option. In the UK, top-tier law firm Baker & McKenzie has a global practice on intellectual property whose past clients include Calvin Klein and L'Oreal. Senior associate Julia Dickenson says she advises her fashion clients to scope out the problem first to see where consumers are being misled in order to strategically target counterfeiters.

Dickenson says there is a “huge volume of low-level infringement,” which can be stopped by takedown notices to auction sites, or disruption techniques like taking away domain names. But as companies uncover the links between specific cases of infringement, they often see “there are fewer people but more important targets,” she adds. It’s these criminals who brands can target with civil and even criminal proceedings.

“We tend to do a bit of a mixture of everything. We would look at what that person is doing, if they’re clearly selling counterfeit products and we know we can meet the higher bar of showing criminal behaviour then we would get the police involved, or we could field a private criminal prosecution and the court orders the police to pick that up,” explains Dickenson. “Or we would commence civil proceedings, and, what we tend to find, brands prefer civil proceedings as we have control over those and the damages are easier to share.”

A site-blocking injunction is also a useful measure if a fake website is being run in a foreign country where filing court proceedings are more difficult, Dickenson adds. In the past this technique has forced Internet service providers to block access to website selling fake items. An injunction might also result in the recovery of damages and payment of legal costs.

ADVERTISEMENT

Take Richemont, the luxury conglomerate that owns Cartier and Chloe. Last July, the UK Court of Appeal ruled in its favour, upholding a decision forcing Internet service providers like Sky and TalkTalk to block websites selling counterfeit bracelets purporting to be from Richemont brands.

“Its definitely a battle, and it’s a battle that we’ve seen in the past in the physical world but obviously the nature of online means its so much easier to set up anonymously, to set up multiple sites, to avoid knowing who is behind it,” Dickenson continues. “You have to be realistic. The problem isn’t going to go away in the near future, but that doesn’t mean you should admit defeat. Where we’ve seen the most success is where we have been realistic but ambitious and we have formed a co-ordinated cohesive strategy.”

Related Articles:

[ Can New Technologies Thwart Counterfeiters?Opens in new window ]

From analysis of the global fashion and beauty industries to career and personal advice, BoF’s founder and CEO, Imran Amed, will be answering your questions on Sunday, February 18, 2024 during London Fashion Week.

The State of Fashion 2024 breaks down the 10 themes that will define the industry in the year ahead.

Imran Amed reviews the most important fashion stories of the year and shares his predictions on what this means for the industry in 2024.

After three days of inspiring talks, guests closed out BoF’s gathering for big thinkers with a black tie gala followed by an intimate performance from Rita Ora — guest starring Billy Porter.