The Business of Fashion

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

NAIROBI, Kenya —For a long time, in the eyes of the world, the idea of Africanness has remained static. The focus on heritage – often meaning a snapshot of the past – has overshadowed the wider shifts into a globalised, more equal understanding of Africanness.

It was essential to present Africans primarily in this revisionist way, so that the moral complexities of how particular (and often unpleasant) elements of modernity reached African shores could continue to be avoided. However, the weights of old histories and power dynamics continue to play a significant role in fashion and art, whether consciously or unconsciously.

These philosophies place African bodies lowest on a hierarchy of disadvantage, meaning that the lens of a Western researcher into African cultures is often that of a curious onlooker fascinated by the exotic. This viewpoint also leans heavily towards the perception of the pristine African, undamaged by Western interaction, perhaps in a bid to cover the violence of colonial reality. But in a changing world, where conversations in the post-colonial space among Africans on the continent and people of African descent in the diaspora are gaining traction and value, difficult questions are being asked about the place and authority of the universal white gaze.

Fashion designer Kepha Maina's Avaris collection | Photo by Sunny Dolat

ADVERTISEMENT

As Africans embrace the discomfort of a re-emerging self-esteem, new generations of Africans are taking back the ability to name, prioritise and create African spaces beyond developmental lack and industrial aspirations. These generations must assume the power to describe and analyse their own worlds relative to their diverse points of view.

“There’s a shift that’s happening with the new generation of African designers, because we’re creating products that have global appeal. Someone in New York, Seoul, Sydney or Paris could look at my dress and ask, 'where’s that from?' It shouldn’t be obvious that a piece is from Africa just because it’s made from wax print [of African motifs],” says Nairobi-based fashion designer Anyango Mpinga.

Fashion, art and culture are far from the only windows through which African re-imaginings and reclamations can take place, but they are a more than worthy arena for essential debates to begin.

A Kenyan Perspective

“My aesthetic confused people at first,” says Katungulu Mwendwa, a contemporary Kenyan fashion designer known for her minimalist approach. “Some people would even say [to me], ‘Is that African? But there’s no print!' I realised some people have a very narrow definition of Africa and it rarely ventures out of heavy, bold print and colour.”

Constructions of urban Kenyan contemporary culture continue to take many shapes and forms, with few more interesting than the area of fashion and apparel. The self-rule of our nation after it gained independence from Britain engendered an exploration of universal equality — if a Kenyan was able to shop for and buy the same garment as anyone else in the Commonwealth, it was a celebration of the access that had not been available before, and the ability of the newly free young people to define what was then possible for their own lives.

Difficult questions are being asked about the place and authority of the universal white gaze

A push began to promote and stabilise cotton production in Kenya, though it failed under subsequent political regimes. This economic failure, which also occurred in other agricultural spheres, was followed by structural adjustment programs by the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank, looking to open out the previously protected infant industries to free market trade opportunities and global supply chains.

To combat sticky colonial legacies despite these challenges, a desire for more conscious expressions of blackness began taking root in a new generation on the continent, with people beginning to demand certain levels of Africanness from their clothes to link more strongly with their cultural origins and heritage. With this came the culture and politics of wearing so-called African fabrics, the most ubiquitous of which is ankara.

ADVERTISEMENT

The origin of wax print in Africa is commentary on the power imbalances within international supply chains. It was created by the Dutch in a failed bid to mass-produce Indonesian batik fabric that was usually handmade, to gain a market by the ability to offer it to consumers cheaply. When an African market was found for the rejected cloth in the 19th century, the original Indonesian designs were replaced by local ideas and motifs, to increase their relevance to their new clientele. China then joined the industrialisation race, manufacturing wax print at cheaper rates and successfully overturning the Dutch monopoly.

Outfit by M+K designed by Muqaddam Latif and Keith Macharia |

Photo: Maganga Mwagogo

The ankara debates, therefore, are a serious conversation about the politics of origin, assimilation and belonging. The fabric clearly does not pass basic global standards for rules of origin, to rightfully earn the label ‘African’, based on the location of the last substantial transformation before it arrived on our shores for our use. However, does calling it African for centuries actually make it so? Does being its majority users and manipulating it in increasingly innovative ways make it irretrievably ours? Is it odd that fabrics that have been made by others and travelled so far have a belonging to our sense of self that supersedes that of textiles actually woven or fabricated on our shores?

It can seem strange that we consider a pattern on a piece of cloth as such a site for cultural contest. For us, this hyper-analysis of ankara is underpinned by the Western looting of the tangible artefacts to which cultural meaning is assigned. Having artefacts taken away during colonialism deeply and irreversibly interrupted our senses of origin and belonging. Subsequently, Kenyan culture has appropriated the remaining symbols — such as Maasai cultural goods and experiences — to serve the need and desire for both nation building and belonging.

“I have always loved prints. However, I have never wanted what we have so fondly come to refer to as ‘African prints’ to define my authenticity as an African designer,” explains Anyango Mpinga. “I take pride in the fact that my designs are African by virtue of my heritage and traditional influences. [And even] when I started designing my own prints, I didn’t want them to be another take on the Maasai or Turkana. Both ethnic groups have a distinct aesthetic, but these distinctions do not define the multicultural landscape that makes up our country.”

Regardless of its source, a critical mass in West Africa had used ankara (wax prints) almost exclusively for a long time. As hunger and effective market demand grew across the continent for identifiers of Africanness, wax print was easily taken on in other regions as a pan-African symbol, despite the fact that its symbols and patterns were specifically designed to have special meaning for communities in West African countries.

In West Africa, extravagance is a cultural statement. Here in East Africa, toning it down <i>is</i> the statement

Copying any garment in wax print became the singular textile representation of the African continent, an idea given legs when black diaspora celebrities in the global North gave it visibility and a seal of approval by wearing it proudly. It became easier to design with wax print than anything else, leading to a dearth of actual design — pushing the marriage of colour, cut, theme, drape, texture and fabric in order to explore new volumes and silhouettes.

However, Kenya has been known as a net consumer of all kinds of cultural content from all over the world, and this cosmopolitan litany of influences — including those from the diversity of ethnicities in our geography — has lent to our creative practices an eclectic quality that is difficult to pin down or describe under one label.

ADVERTISEMENT

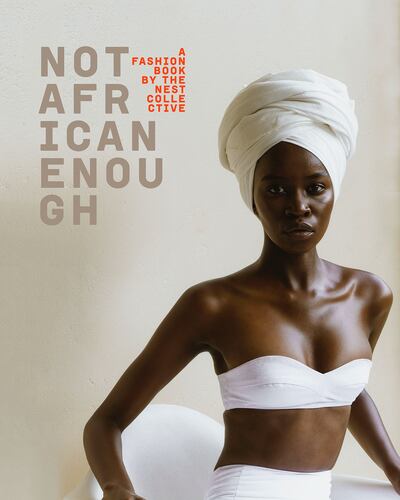

'Not African Enough' (2017) book by The Nest Collective featuring outfit by Firyal Nur

Photo: Maganga Mwagogo

“Many Kenyan designers are making clothes and accessories with themselves in mind,” offers accessories designer Ami Doshi Shah. “Our personal aesthetics really come into play and that’s why there is less use of wax print. Our approaches have more to do with our evolution as Kenyans rather than how the outside sees us evolving as [the entire African] continent.”

“We’re not extravagant as Kenyans. We’re culturally trained to never be over-the-top because there’s no need, you know? In West Africa [by contrast], extravagance is a cultural statement. Here, toning it down is the statement,” she adds.

New African world views — around value, culture, significance, and the potential for futures beyond colonial crippling — are essential for Africa to begin to generate and evolve its own autonomous agenda. That is why we at The Nest Collective published a book entitled "Not African Enough" to aim to dismantle this heavy super-concept "African;" the assembly of words, images, sounds, ideas, weaknesses, histories and failings associated with the entire continent.

In fashion terms, this is our way to say that we are more than visibly African fabrics like kitenge, khanga, kikoi and ankara. We in Nairobi are not West African—we are East African, Kenyan, particular and individual.

Perhaps most importantly we aim to unapologetically contextualise and position black African bodies as beautiful renderings of humanity, in resistance to the pervasive tokenism, exotification and fetishisation of blackness in global fashion conversations. The idea of our designs, our thinking or anything else being “not African enough” is a ruse. We assert our right to be more than enough.

Sunny Dolat is a Kenyan creative director, production designer and member of The Nest Collective. The fashion book, ‘Not African Enough’, was published in 2017 by the Nest Arts Company Limited

Related Articles:

[ Vlisco, the African Fashion Titan from HollandOpens in new window ]

[ African Menswear Goes GlobalOpens in new window ]

[ What Will it Take For Africa to Join the Global Fashion System?Opens in new window ]

From analysis of the global fashion and beauty industries to career and personal advice, BoF’s founder and CEO, Imran Amed, will be answering your questions on Sunday, February 18, 2024 during London Fashion Week.

The State of Fashion 2024 breaks down the 10 themes that will define the industry in the year ahead.

Imran Amed reviews the most important fashion stories of the year and shares his predictions on what this means for the industry in 2024.

After three days of inspiring talks, guests closed out BoF’s gathering for big thinkers with a black tie gala followed by an intimate performance from Rita Ora — guest starring Billy Porter.