The Business of Fashion

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

The author has shared a YouTube video.

You will need to accept and consent to the use of cookies and similar technologies by our third-party partners (including: YouTube, Instagram or Twitter), in order to view embedded content in this article and others you may visit in future.

This article appeared first in The State of Fashion 2020, an in-depth report on the global fashion industry, co-published by BoF and McKinsey & Company. To learn more and download a copy of the report, click here.

LONDON, United Kingdom — For many years, "diversity" in fashion meant occasionally putting a non-white face on a magazine cover. Diversity was often more about visual impact than being representative. Today, these token nods to diversity are beginning to give way to real inclusivity as the industry moves from eye-catching imagery towards meaningful change in the workforce. This is motivated by consumers demanding that companies' values reflect their own, and by employees and stakeholders clamouring for change.

We expect companies will start to broadcast their diversity credentials loudly and proudly, with chief diversity and inclusion officers becoming the rule rather than the exception. Customers will keep a keen eye on whether these initiatives are style over substance, rewarding those who embed change throughout their organisations and calling out, shaming or boycotting those who don’t.

Models dance on the runway at the Tommy Hilfiger TommyNow fall

runway show at the Apollo Theatre in New York City. Angela Weiss/AFP/Getty Images

ADVERTISEMENT

In consumer-facing aspects of the business, representation is finally improving. There were more than twice as many models of colour on the runways of the autumn 2019 fashion shows as there were for spring 2015 — up from 17 percent to almost 40 percent. One powerful example was Gen-Z superstar Zendaya's collaboration with Tommy Hilfiger, which used only black models at its Paris launch — 59 of them, of different sizes and ages. Rihanna's diverse show for her lingerie line Savage x Fenty was lauded by the industry as a riposte to competitor Victoria's Secret long-projected homogeneous view of beauty. capsule collections are also visibly embracing diversity: Asos has released three collaboration collections with GLAAD, giving the LGBTQ acceptance organisation 100 percent of profits.

In an industry that has often fallen back on "artistic licence" to justify its choice of homogeneous visual imagery, that is no longer an excuse that works. Consumers today increasingly express their disdain if diversity is not represented or considered. Victoria's Secret's long refusal, until recently, to use transgender models because, to quote the chief marketing officer "the show is a fantasy," is one well-known example. Consumer backlash can be swift and brutal, often resulting in changes to corporate policies. After the PR crisis related to Gucci's "blackface" jumper, for example, the brand invested $10 million into a programme that aims to encourage internal diversity and inclusion.

The impact of mistakes and misjudgements in this area is not just felt on social media. Almost two-thirds of consumers are self-proclaimed “belief-driven buyers” who will choose, switch, avoid or boycott a brand based on its stand on societal issues — a statistic that holds broadly true across markets as diverse as China, Brazil, the US and Germany. And it’s not just what they buy, it’s where they buy it: more than half of 21-to-27-year-olds in the US believe that retailers have a responsibility to address wider social issues with regards to diversity.

Beyond its workforce, the ultimate visible expression of a company’s commitment to diversity and inclusion is its products. Challenger brands are already launching products that cater to underserved demographics, from adaptive fashion brands such as IZ Adaptive, to Good American, which offers jeans in a wide range of tailored sizes; from the growing number of modest clothing brands aimed at Muslim women to trans-friendly lingerie brands such as London-based Carmen Liu Lingerie.

Some incumbent brands are recognising that these companies are carving out profitable niches and are responding accordingly. Anthropologie, for example, has launched Anthropologie in sizes from 00P to 26W, while Tommy Hilfiger launched a line of adaptive clothing for children with disabilities and later added adult apparel. With the adaptive-clothing market estimated to reach almost $400 billion by 2026, more high-street brands are launching adaptive-clothing ranges, including Zappos and Target.

If further motivation is needed, while society certainly expects greater representation of difference, there is also a strong economic case for diversity (which, as we’ll see later holds true within companies too). In the US, for example, the buying power of people of colour is growing significantly faster than that of the white population. The implication for fashion players is that sales rise significantly as more customers feel visibly represented and aligned to the brand in terms of shared values.

Almost two-thirds of consumers are self-proclaimed 'belief-driven buyers.'

However, if companies are to parade their diversity credentials, they need to make sure they are genuine and deep-rooted. In other words, the fashion industry needs to live the message, not just parrot it. That means putting as much if not more focus on the internal organisation as on their models’ skin colour.

There is substantial room for improvement. A New York Times article recently called out Adidas, whose employees criticised the company for a lack of diversity when they realised that less than 5 percent of the workforce at its US headquarters identified as black. Nike is among others who have also now come under fire. "Examine fashion's underlying power structure, what you find is male, cis-gendered whitewashing," wrote Jason Campbell in an op-ed for The Business of Fashion. "Data is limited, but a close look at the executive committees at major fashion companies shows that they are packed with white men."

ADVERTISEMENT

Some companies are taking positive action. LVMH has pledged equal gender representation for executives by 2020, while Nordstrom claims it has achieved equal pay for employees of all genders and races and is close to approaching equal representation. Public announcements of such initiatives may seem self-aggrandising, but today's belief-driven customers look beyond the glossy imagery to decide if a brand's values match their own.

Some of the industry's most recognised players, such as Chanel, Gucci and H&M, have hired executives devoted to diversity to show their commitment, but employee training and full integration across functions still lags across the industry. A 2019 US fashion industry report revealed that only 56 percent of respondents said they had taken a professional class or workshop related to inclusion and diversity.

Making diversity the norm, rather than a special initiative, will ultimately have the biggest impact on corporate culture. Consider gender and ethnic representation in leadership positions. Women are overrepresented in the industry with more than two-thirds of fashion house employees being women in 2018, yet once you move up to the C-suite, this number drops to less than a third. This is still well above the global average of 14 percent, but parity seems a distant dream.

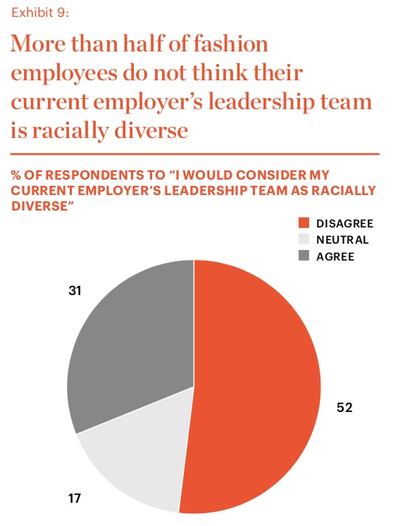

Similarly, there are only a handful of black creative directors, like Olivier Rousteing and Virgil Abloh, at the helm of high-profile luxury fashion houses, and there are scant few C-suite executives of colour to be found anywhere in the industry. It is evident that while there is some progress across the industry, there remain bastions where progress is slow, particularly in creative leadership, decision-making and technical roles, from creative directors and business unit heads to chief operating officers and chief technology officers.

“If industry leaders need motivation beyond the moral imperative and the positive impact on creativity, our research has built the business case for diversity,” says Vivian Hunt DBE, managing partner for McKinsey in the UK and Ireland. “Diversity is correlated with superior company economic performance, a finding which is reinforced year-on-year.” Recent McKinsey research into the impact of diversity on organisations shows that companies ranked in the top quartile for gender diversity in their executive teams were 21 percent more likely to have above-average profitability than companies in the bottom quartile, but also 27 percent more likely to have industry-leading performance on longer-term value creation. For ethnic and racial diversity, top quartile companies were 33 percent more likely to outperform national industry peers. “Combining an inclusion and diversity strategy with the core imperatives of a business means that inclusive leadership really does lead to inclusive growth,” continues Hunt.

In 2020, visible expressions and public statements of diversity and inclusion will be more frequent, and companies will not be shy about sharing them. But they will also be vocal about their broader commitment to diversity and will be held to account by employees and customers. Fashion players should articulate their own business case for diversity while having a clear understanding of how much better diverse teams are across functions, from customer insight and product innovation, to marketing and digital. Chief diversity officers will become more common, better resourced and further empowered, laying out ambitious roadmaps for initiatives such as workforce training, strategies to improve diversity in key creative and corporate roles, and improving inclusion-related indicators.

The core business must own the diversity and inclusion agenda beyond the chief diversity officer, with inequality in the workforce addressed by efforts to de-bias recruitment and advancement processes, provide sponsorship and leadership development programmes for diverse talent, ensure the workplace caters for employees of all genders, races and abilities, and by promoting equal pay and opportunities. In a female-dominated industry, average representation will be insufficient as a target; businesses should use cascade targets to increase representation in specific areas of the business, with managers held to account while being supported in meeting these targets. Overall, companies should consider how to transform their organisations to create a truly inclusive culture for employees and consumers, eschewing a skin-deep veneer of change for profound and lasting reform.

From analysis of the global fashion and beauty industries to career and personal advice, BoF’s founder and CEO, Imran Amed, will be answering your questions on Sunday, February 18, 2024 during London Fashion Week.

The State of Fashion 2024 breaks down the 10 themes that will define the industry in the year ahead.

Imran Amed reviews the most important fashion stories of the year and shares his predictions on what this means for the industry in 2024.

After three days of inspiring talks, guests closed out BoF’s gathering for big thinkers with a black tie gala followed by an intimate performance from Rita Ora — guest starring Billy Porter.