The Business of Fashion

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

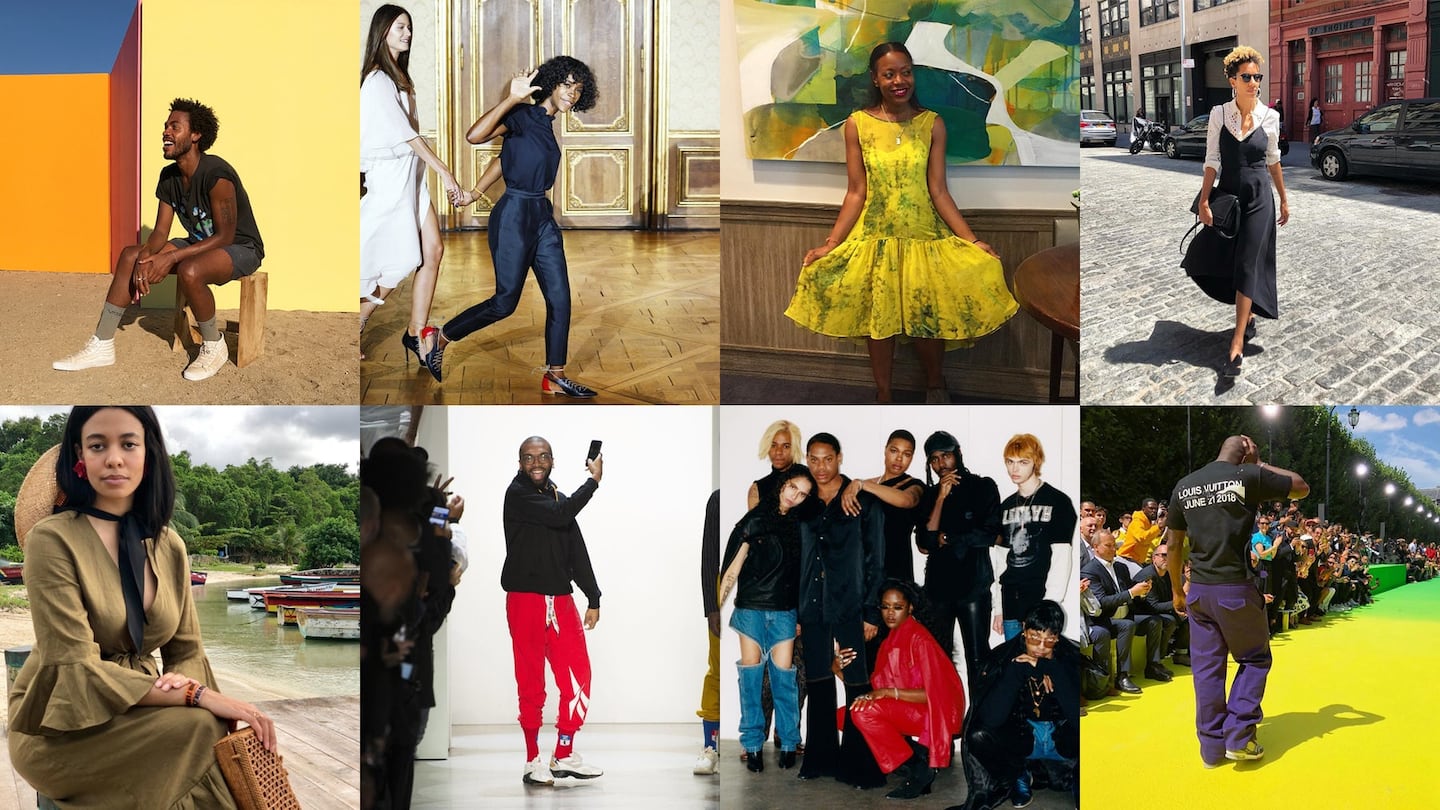

PARIS, France — African American designer Virgil Abloh's first show as men's artistic director for Louis Vuitton, one of the biggest luxury brands in the world, was a true fashion moment. The Spring/Summer 2019 outing — colourful, inclusive, joyful, emotional, raw, uplifting and lauded by critics and consumers alike — sparked a cultural revolution at the French luxury megabrand. In a business that continues to struggle with whitewashed runways and boardrooms, where racial minorities are scarce, Abloh's debut underscores a key point: diversity is not only a moral obligation, it's imperative to keeping the industry relevant at a time when black creatives, especially in music, are at the very centre of popular culture.

Abloh, who was raised in the Midwest of the United States, is not the first black man to stand at the creative head of a major European fashion label. Olivier Rousteing currently oversees Balmain; Shayne Oliver spent time as a "designer-in-residence" at Helmut Lang; Maxwell Osborne co-led the creative direction of DKNY; Patrick Robinson once served as artistic director at Paco Rabanne and, back in the late 1990s, Edward Buchanan was design director at Bottega Veneta.

But these appointments have been few and far between, signalling the yawning gap between a post-racial fashion industry and today’s reality.

In the US, in particular, African American designers still face undeniable, difficult-to-break down roadblocks, meaning designers of colour have struggled to rise to the pinnacle of the American fashion industry. While Stephen Burrows and Geoffrey Banks have led distinguished careers, they never reached the same level of success — in terms of both the size of their businesses as well as name recognition — as others in their generation, such as Calvin Klein, Ralph Lauren and Diane Von Furstenberg.

ADVERTISEMENT

And the pattern does not appear to be letting up. Consider Charles Harbison, who launched his collection in 2013. That September, he was featured in American Vogue. InStyle called him a “designer to bank on.” Beyoncé and Solange Knowles wore his clothes. And yet, his company is currently on hiatus, unable to secure the financing needed to develop, manufacture and market its products.

“The fact that I'm not showing new work every season with my name on it, yes I do mourn that. It's my heart calling,” said Harbison. “I am the happiest and most excited, and I feel the most useful in the world, when I’m heralding the ideas that mean a lot to me and presenting artful work that I think is valid in our lives. I always feel like I'm doing that when I'm operating under Harbison in a real way.”

It comes down to money. You pretty much have to buy a seat at the table, especially if it's a white table.

Harbison is keeping busy with consulting roles: he’s currently the head of design for Nicholas, an Australian-born contemporary clothing label now headquartered in Los Angeles, where he lives. (He was also in talks with Ungaro earlier this year, but those discussions fell off.) He hopes to parlay some of his income from the Nicholas role into resurrecting his namesake label.

Industry veteran Tracy Reese, arguably the most well-known black designer in the world — and a favourite of former US First Lady Michelle Obama — has managed to sustain her business for 22 years. It is now majority-owned by a consortium of investors. She believes engaging more investors from the black community could help improve the survival rates of black-owned fashion labels. “Black investors have to get with the programme,” she said. “We have to approach this from a different perspective, because it does come down to money. You pretty much have to buy a seat at the table, especially if it’s a white table, or a white-run table.”

Reese also believes the onus is on the fashion industry at large to better support black talent: executives need to hire black designers at brands that capitalise on black culture, and retailers need to support independent black designers by making a concerted effort to seek out and buy their collections. “We’re in a time where forward-thinking people are hungry for change and correction,” she said.

To be sure, many of the challenges facing black designers — in particular, difficulty securing capital and reaching consumers — are the same challenges facing white designers. "Reaching the level of a Valentino or a Ralph Lauren is a little bit like getting to the NBA, or winning the Super Bowl," said Robin Givhan, fashion critic at The Washington Post, "I mean, honestly, where is the next Ralph Lauren anywhere?"

Still, some say good old-fashioned racism is what’s keeping designers of colour from reaching the heights of their white counterparts. Since there are very few examples of designers of colour in the space, investors are wearier, and the cycle remains unbroken.

"I think we can just assume from the start that there's challenges for people of colour in the industry," said Steven Kolb, president and chief executive of the Council of Fashion Designers of America (CFDA). "We need to make that a starting point and really focus on how we can improve as an industry."

ADVERTISEMENT

Tracy Reese Spring/Summer 2018 | Source: Courtesy

To do this, Kolb has met with several individuals who are dedicated to solving fashion’s diversity problem including fashion activist Bethann Hardison; Brandice Daniel, founder and CEO of Harlem’s Fashion Row; and Hannah Stoudemire, co-founder of Fashion For All Foundation. His goal is to gather as much knowledge as he can about the issue and pinpoint the specific roadblocks that are holding black fashion professionals back. Kolb is adamant that this work must stretch from the design studio to the boardroom.

It's clear that, over the past few years, the American fashion industry has made a concerted effort to better engage the black design community. Kerby Jean-Raymond of Pyer Moss, Laquan Smith and Telfar Clements of Telfar (winner of the 2017 CFDA/Vogue Fashion Fund) are all black designers that have recently been embraced by the fashion establishment. Azede Jean-Pierre, Recho Omondi, Jerome LaMaar, Omar Salam of Sukenia, Fe Noel, Kimberly Goldson, Sammy B and Mimi Plange are other notable black designers the industry is watching, some with more fervour than others.

This year’s CFDA nominees included black designers Jean-Raymond in the Swarvoski Emerging Talent category and Abloh, who is also the founder of haute streetwear label Off-White, for both Menswear and Womenswear Designer of the Year. Accessories designer Aurora James of Brother Vellies (winner of the 2015 CFDA/Vogue Fashion Fund) was also nominated for the Swarvoski Emerging Talent award.

However, none of them won. “Do I think that there's a representative percentage of readily available, working, producing, black designers out there? No, there isn't,” Givhan said. “But do I think that the landscape is better than it was a decade ago? Certainly.”

There is also the tricky matter of whether being labelled a “black designer” presents its own challenges, forcing rising talents to distance themselves, at least publicly, from black culture in order to resonate with the industry. Abloh and Jean-Raymond both declined to be interviewed for this article, and Jean-Raymond has been vocal in the past about being uncomfortable with this. By saying “black designer,” there is an inherent perceived otherness, perhaps exacerbating the problem.

Is there a representative percentage of black designers out there? No, there isn't.

“I think once you start sort of labelling brands as “black” or a designer as “black,” you end up with a situation like we had back in the 1990s with ‘urban fashion,’” Givhan said, referring to the group of labels run by designers of colour who came to prominence in the era — including Sean John, Phat Farm, Rocawear and FUBU — only to be relegated to a certain moment, place and aesthetic. “There was this sense that regardless of what the clothing looked like, it was, the ethnicity of the designer that almost determined how the fashion was categorised, or where it was placed in a department store.”

“It can often times feel like there is a narrowing of my significance as a designer by way of this one identity of mine in a way that white designers, Asian designers and Latin designers don’t really have to take on,” Harbison said. “So, it can be frustrating, because as an entrepreneur it can feel like this one identity that I know is problematic in business, is being that much more emphasised. And potentially making my business that much more difficult.”

ADVERTISEMENT

At the same, “black” can be read as authenticity. While Harbison says the majority of his clientele are white women: “customers who aren’t black can find beauty in black narrative,” he explains. “I don’t resent this choice at all because I love being black. And so, my blackness is very much a part of the identity and not to the dismissal of anyone else — but it’s just offering clothing from a different point of view for every client.”

Carly Cushnie, the New York-based black designer behind the label Cushnie et Ochs — who recently broke ties with her design partner Michelle Ochs — adds that while being at the helm of a namesake brand comes with its challenges, it also presents a tremendous opportunity to support diversity.

"I'm focusing on pushing the brand forward and having the opportunity to champion women of colour, and support more women of colour going forward," said Cushnie, whose clothing has been worn by Michelle Obama, Meghan Markle and Ashley Graham, among others. She was also the first black woman designer to be nominated for the CFDA Swarovski Award.

“[Abloh’s appointment at Louis Vuitton] is huge step forward, just in the same way Edward Enniful’s appointment at British Vogue was as well,” she added. “I think it’s an exciting time for people of colour across the industry.”

Related Articles:

[ Fashion Has a Diversity Problem on the Business Side, TooOpens in new window ]

[ The Truth Behind Fashion’s Most Diverse Season EverOpens in new window ]

From analysis of the global fashion and beauty industries to career and personal advice, BoF’s founder and CEO, Imran Amed, will be answering your questions on Sunday, February 18, 2024 during London Fashion Week.

The State of Fashion 2024 breaks down the 10 themes that will define the industry in the year ahead.

Imran Amed reviews the most important fashion stories of the year and shares his predictions on what this means for the industry in 2024.

After three days of inspiring talks, guests closed out BoF’s gathering for big thinkers with a black tie gala followed by an intimate performance from Rita Ora — guest starring Billy Porter.