The Business of Fashion

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

NUTLEY, United States — Inside a cluttered laboratory on a sprawling corporate campus in the New York suburbs, Modern Meadow is attempting a feat of modern alchemy: turning a vat of liquid the colour and consistency of chicken soup into luxury-grade leather.

The sweet, syrupy liquid is food for a strain of yeast that has been genetically modified to produce collagen, the essential biological component of everything from calf leather to alligator skin. Make collagen in big enough quantities and figure out how to turn it into a workable material, and the seven-year-old start-up thinks it just might engineer the biggest fabric innovation since Lycra: lab-grown leather.

Some in the $2.4 trillion apparel industry are eager for a future when leather, fur and silk can be grown in labs, instead of harvested from living creatures. Humans have been making clothes and shoes from animal products for millennia; the earliest leather-working tools date back to the Palaeolithic era. And, today, consumers spend tens of billions of dollars on leather, fur and silk apparel, accessories and footwear annually.

But their use is becoming more controversial. Raising cattle contributes to climate change and requires enormous amounts of land and water, two resources that are growing scarcer by the year. Ranchers may also be tempted to cull their herds if global beef consumption maxes out, as some predict, depriving the fashion industry of a major source of hides. Luxury houses like Hermès and Chanel have acquired tanneries to guarantee future supplies of high-quality materials.

ADVERTISEMENT

Meanwhile, brands like Gucci, Versace and Michael Kors have stopped using fur amid growing public outcry over animal welfare, and some analysts predict younger consumers in Western countries will buy fewer products made from animals generally. Luxury brands that rely on leather-working techniques perfected decades ago fear losing customers to rivals that are developing innovative new fabrics, from jackets and yoga pants made with moisture-wicking, breathable synthetics to ultra-light shoes that boost performance.

Analysts predict younger consumers in Western countries will buy fewer products made from animals generally.

Several start-ups are attempting to bioengineer solutions to these problems. Modern Meadow has dozens of patents and over $50 million in funding to pursue its lab-grown leather. Bolt Threads, based in Emeryville, California, across the Bay Bridge from San Francisco, has raised over $200 million to trick yeast into producing spider-silk proteins and, in September, will begin taking pre-orders on a bag made out of a leather-like material grown from mushroom roots. VitroLabs, also based in San Francisco, is using stem cells to grow leather that's indistinguishable from the real thing and hopes to release a product made from the material next year, said co-founder and chief executive Ingvar Helgason.

Now, fashion heavyweights are getting behind this technology too. Nike was awarded a patent last year for shoes and other products that incorporate leather "cultured" in a lab. Adidas is working with AMSilk, headquartered outside Munich, to develop a biodegradable sneaker from a silk-like product that can be spun, sprayed or turned into a gel. Bolt Threads counts Patagonia and Stella McCartney as its customers, and Kering and PVH are among the backers of an incubator that supports start-ups developing leather alternatives made from unconventional sources like apples and yeast.

At Kering, investment in alternative fabrics and other disruptive innovations is a core part of the company's goal of reducing its environmental footprint by 40 percent by 2025, said Marie-Claire Daveu, the company's chief sustainability officer. Still, she said lab-grown leather may be a decade away from being incorporated into products sold by Kering's brands, adding that it's difficult to anticipate the course such a new technology will take.

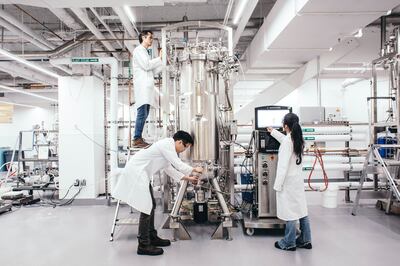

Process development unit at Bolt Threads | Source: Courtesy

But when the material is ready, demand will be there, she believes. Sustainably sourced, cruelty-free fabrics are “becoming more and more important for our customer,” said Daveu. “If you make a proposal to the customer with innovative raw materials that are also very good for the planet and for the people, they will be very interested.”

For now, fashion’s lab-grown future is mostly confined to vats in labs like Modern Meadow’s facility in New Jersey. The company compares its technology to synthetic fabrics: first developed in the early 20th century, they climbed in popularity over the decades, with polyester surpassing cotton as the most commonly used fabric in the early 2000s. Today synthetics are blended seamlessly into a wide variety of apparel, from suits to socks.

“The next few years are about us really deploying and maturing [our] capabilities and then bringing them to market with partners,” said Andras Forgacs, co-founder and chief executive of Modern Meadow. “This is not about taking over the world next month.”

ADVERTISEMENT

The basic recipe for growing fabric in a lab is roughly the same whether you’re hoping to make spider silk or alligator skin. First edit yeast DNA so the strain produces collagen when it ferments. Feed in nutrient-rich water and churn vigorously, causing proteins to form inside the yeast cells, which can then be extracted for the creation of fabric. Customise the DNA in just the right way, and a hyper-efficient protein factory is born.

VitroLabs uses a different technique, coaching stem cells derived from animal cells to form layers of skin. Bolt Threads’ mushroom roots, called mycelium, are also left to grow in trays until they form the basis for a material resembling leather.

Many of these processes rely on techniques developed decades ago that were until recently so difficult and expensive that they were used mainly in the pharmaceutical industry. But over the last decade, costs have plunged to the point where even small fashion-focused start-ups can access equipment to edit and splice DNA.

Modern Meadow tests about 1,000 modified yeast strains per week, with 1 or 2 percent deemed worthy of fermenting, and a fraction of those entering regular production. Its yeast cultures produce about 20 times as much protein as they did two years ago. Bolt Threads created its first microsilk in 2010 and needed seven more years to make enough to release its first product: a tie sold in a limited run of 50, for $314 each. If that sounds expensive, the same amount of lab-grown silk used in one tie would have cost tens of millions of dollars a decade earlier, said Dan Widmaier, Bolt co-founder and chief executive.

For most of these start-ups, the goal is not to create one perfect fabric, but to design a platform that can launch multiple new materials. Already this year Bolt Threads has released a second fabric, resembling felt, and believes it can develop new materials from scratch in under a year, Widmaier said. VitroLabs can reliably produce animal skin in a lab setting and believes it can create fur by introducing the stem cell type tied to hair production.

The goal is not to create one perfect fabric, but to design a platform that can launch multiple new materials.

“At the end we’ll have a process that can make stuff that feels like silk, stuff that feels like wool, stuff that feels a little more like nylon... in theory anywhere you want to slot it into,” Widmaier said. “[The science] continues to get better at an ever-increasing pace.”

The secret sauce is what comes next: combining those proteins into structures inspired by leather or silk — or completely new materials. Rather than just imitate leather already on the market, Modern Meadow is experimenting with material that pours like water or can be sprayed onto textiles in a thin sheen. VitroLabs is working on crocodile skin that forms scales in customisable patterns, such as a company logo. AMSilk has developed an ultra-strong material to replace petroleum-derived fabrics in footwear and in gel form to replace silk in cosmetics.

The possibilities are endless, but the public has had few glimpses of finished products from any of these start-ups. Last year, an installation at the Museum of Modern Art in New York included a white T-shirt that incorporated Modern Meadow’s material, as well as a gold Stella McCartney dress that used Bolt Threads’ microsilk. A Stella McCartney bag made from Bolt Threads’ mushroom-root leather is on display at the Victoria & Albert Museum in London.

ADVERTISEMENT

Having solved many of the most difficult scientific questions, the objective now is to make enough raw material to produce a commercially viable product, graduating from five-litre containers in labs to 200,000-litre vats in factories.

Earlier this year, Modern Meadow partnered with Evonik, a German manufacturer that specialises in chemical production. The goal is to flood the start-up’s materials research team with protein, speeding up the development process. Some of Bolt Threads’ raw material is produced by Ecovative, a Green Island, NY-based company that developed the process and grows mycelium into packaging and other industrial products. Bolt has also hired a manufacturing partner to scale up output.

Biofabrication start-ups say they’ve been deluged with requests by designers to produce bags, shoes and apparel made from lab-grown fabrics.

A biology lab for growing cruelty-free materials | Source: Courtesy

Modern Meadow chief creative officer Suzanne Lee said the brands that have been most interested aren’t the “tree hugger” crowd. She said that’s ultimately a good thing: it’s easier to hit the mainstream if Modern Meadow can position its product as a fabric that luxury houses will use for decades, rather than to wow audiences in a single fashion show.

“It’s definitely not the novelty factor,” she said. “You don’t spend hundreds of millions of dollars and many years to create something for fashion to end up with for a nanosecond.”

Then there’s the question of what to call these new materials. Modern Meadow branded its material “Zoa,” while Bolt Threads calls its leather-like fabric “Mylo,” after mycelium. The goal in both cases is to create new categories of fabrics that can exist alongside leather, cotton, wool and synthetics — and that consumers will be able to identify and come to care about.

VitroLabs is taking a different approach, seeing a perfect imitation of leather as the key to widespread adoption by the fashion industry.

“Their livelihood is not leather [produced from animal hides], it’s creating products out of leather,” Helgason said. “And if they can find leather that’s more sustainable and environmentally friendly and completely ethical that’s something they will embrace.”

That philosophy may meet resistance from the leather industry. Leather is defined in most countries as coming from animal hide, and companies using the term to market synthetic fabrics — or even material made from leather shavings — have been sued in Brazil and the US. Makers of lab-grown gems — like VitroLabs’ leather, meant to be identical to mined stones — only received permission from US regulators to call their products diamonds in July.

“We’re used to competition. We have a problem when materials that are not leather try and market themselves as leather,” said Mike Redwood, a spokesman for Leather Naturally, an industry group. “Because leather is a brand.”

Still, Redwood said the leather industry needs to innovate, both to reduce the sector’s environmental toll and ensure future supply. He said lab-grown fabrics could prove a substitute for existing leather alternatives derived from fossil fuels.

On this, the leather industry and their new competition agree.

“It’s a very visceral feeling when we touch leather, you have a connection to it in a different way than you do with plastics,” Helgason said. “That is basically the feeling that we want to replicate.”

Additional research contributed by Tamison O’Connor.

This article appears in BoF's latest special print edition.

To receive a copy of BoF's latest special print edition — including the complete index of BoF 500 members — sign up to BoF Professional before November 2, 2018 and enjoy additional benefits including unlimited access to articles, daily members-only insights and analysis and more with your annual membership.

Related Articles:

[ With Lab-Grown Leather, Modern Meadow Is Engineering a Fashion RevolutionOpens in new window ]

[ Fashion’s Fourth Industrial RevolutionOpens in new window ]

Brands including LVMH’s Fred, TAG Heuer and Prada, whose lab-grown diamond supplier Snow speaks for the first time, have all unveiled products with man-made stones as they look to technology for new creative possibilities.

Join us for a BoF Professional Masterclass that explores the topic in our latest Case Study, “How to Turn Data Into Meaningful Customer Connections.”

Social networks are being blamed for the worrying decline in young people’s mental health. Brands may not think about the matter much, but they’re part of the content stream that keeps them hooked.

After the bag initially proved popular with Gen-Z consumers, the brand used a mix of hard numbers and qualitative data – including “shopalongs” with young customers – to make the most of its accessory’s viral moment.