The Business of Fashion

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

MONTREAL, Canada — Like many companies around the globe, Canadian apparel giant Gildan Activewear Inc. pivoted to making hard-to-find personal protective equipment during the pandemic. It's now considering making the temporary business permanent.

Montreal-based Gildan, which usually makes T-shirts, underwear and other basic garments, said April 8 it would start producing non-medical face masks and isolation gowns at its idle Honduras factories to help respond to shortages. Three weeks later, orders keep coming in, and the manufacturer sees opportunities supplying North American customers that have long relied on Asian imports.

“All of a sudden it’s turned out to be much bigger than we anticipated,” Chief Executive Officer Glenn Chamandy said in a phone interview Thursday. “This could become part of our business as we go forward.”

The manufacturer was hit hard by the coronavirus crisis, in part because a large chunk of its revenue comes from selling blank garments to printing companies that customize them for concerts or sporting events. First-quarter sales dropped 26 percent and on Wednesday Gildan predicted a “significant earnings loss” for the current quarter. Its Canadian-listed shares are down 49 percent this year.

ADVERTISEMENT

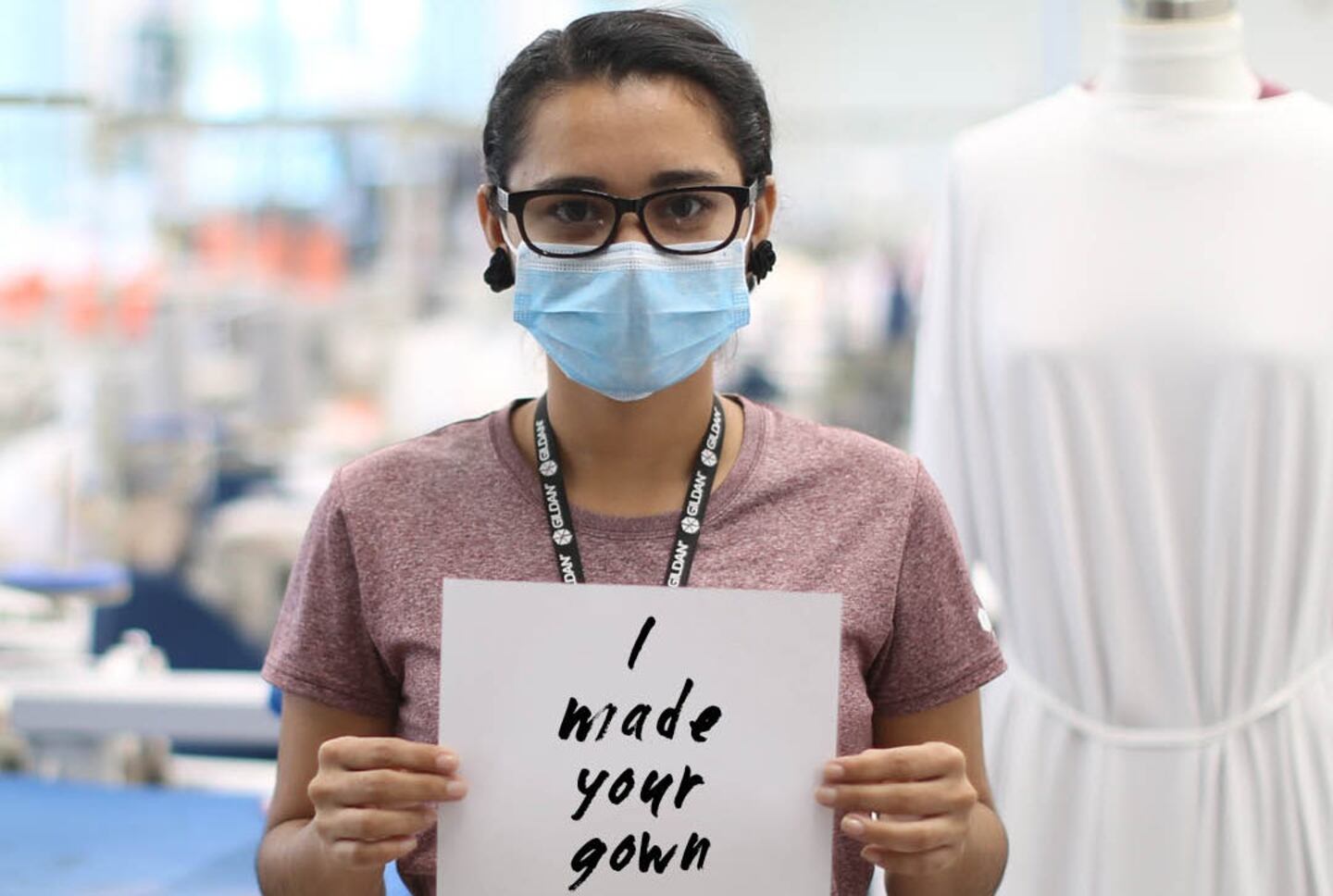

Gildan is planning to make 150 million masks and gowns out of facilities in Honduras and Nicaragua, with a U.S.-based yarn-spinning factory also set to partly reopen for the project. It has been documenting the process on social media, featuring employees who’ve returned to work, while about 95 percent of its 51,000 staff stay at home.

The company is selling the equipment to local governments and to retailers supplying health organizations, particularly in the U.S., Chamandy said. The new endeavour sparked a relationship with big uniform companies that traditionally source protective equipment from Asia and weren’t aware of Gildan’s manufacturing capacity, he said.

Gildan, which also owns the American Apparel brand, has built a global production chain allowing that helps it compete with Hanesbrands Inc. and Berkshire Hathaway Inc.’s Fruit of the Loom. The company spins raw cotton into yarn in the U.S., sends it to Central America to make garments, and ships it back to the U.S., all under five weeks, says Chamandy.

That could be a selling point at a time when the pandemic had stirred international tensions over medical equipment and left governments scrambling to secure supplies in China and fly them back home in time.

“Even though we’re in Central America, we’re an hour and a half away from Miami — it’s not like being in Asia, which is a completely different hemisphere,” Chamandy said. “I think that’s an important part of our success.”

For now, the company is making close to no profit from the equipment, in part because it’s giving some away.

“If we decided to make this a venture as we go forward, obviously it would have to have a good economic return,” Chamandy said.

By Sandrine Rastello.

Nordstrom, Tod’s and L’Occitane are all pushing for privatisation. Ultimately, their fate will not be determined by whether they are under the scrutiny of public investors.

The company is in talks with potential investors after filing for insolvency in Europe and closing its US stores. Insiders say efforts to restore the brand to its 1980s heyday clashed with its owners’ desire to quickly juice sales in order to attract a buyer.

The humble trainer, once the reserve of football fans, Britpop kids and the odd skateboarder, has become as ubiquitous as battered Converse All Stars in the 00s indie sleaze years.

Manhattanites had little love for the $25 billion megaproject when it opened five years ago (the pandemic lockdowns didn't help, either). But a constantly shifting mix of stores, restaurants and experiences is now drawing large numbers of both locals and tourists.