The Business of Fashion

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

NEW YORK, United States — For the past few weeks, Barneys New York, one of America's most important sellers of high-end fashion, has been the talk of the industry — for all the wrong reasons.

In mid-July, Reuters reported that the Manhattan-based luxury department store chain was exploring bankruptcy after a steep rent increase at its Madison Avenue flagship starting in January 2019, which pushed annual rates to $27.9 million, up 72 percent from $16.2 million.

"I want to emphasise that this is an ongoing process and no decisions have been made," Barneys Chief Executive Daniella Vitale wrote in a recent email to staff, which was seen by BoF. The company, which is currently majority-owned by billionaire hedge fund manager Richard C. Perry, is still exploring several options and remains in talks with possible investors and strategic partners.

“We have the best advisors in the business and a team of dedicated financial experts working on strengthening our balance sheet,” Vitale added. “The only thing you need to worry about is serving our customers like you do so well every single day. Our business is operating normally and we are continuing to serve our customers and work with our business partners as usual.”

ADVERTISEMENT

But “business as usual” it wasn’t at Barneys earlier this week, when the vendor that manages “maintenance, cleaning crews and housekeeping” for the Madison Avenue store suspended its work with the retailer, which owed it more than $500,000, according to an email viewed by BoF.

“Trash isn’t being removed, the bathrooms haven’t been cleaned, and it’s a pretty bleak environment here at the moment,” one sales associate wrote to their manager. As of Monday, several of the store’s bathrooms were closed. A spokesperson for Barneys New York declined to address the maintenance matter directly.

“As always, we remain focused on continuing to strengthen our vendor and other contract relationships and supporting the long-term growth and success of our business,” the person said. “The Madison Avenue store continues to run and operate with new merchandise being delivered daily, and our teams look forward to providing our customers with excellent service, products and experiences.”

What happens next remains unknown.

For years, Barneys was America's coolest luxury department store: a temple of fashion that earned a unique place in popular culture thanks to its irreverent take on traditional holiday windows, sharp advertising copy and celebrity fans like Sarah Jessica Parker. In the 1960s and '70s, the store transformed itself from a cut-rate men's suit supplier to a first-class purveyor of hard-to-find luxury labels, earning reputation points for introducing Giorgio Armani to the American market.

In the process, it acquired significant power within the fashion industry, expanding its footprint in the US and beyond. At one time, Barneys could make or break a young designer, an exclusive with the store instantly elevating a label's status. When you were stocked at Barneys, the industry was watching, because everyone was watching Barneys. Brands across the high-fashion spectrum benefited from the Barneys halo effect, including European labels Dries Van Noten and Alber Elbaz's Lanvin, but also American upstarts such as Proenza Schouler and Alexander Wang. And in good times, they also enjoyed robust sales.

But to many industry insiders, the recent reports that Barneys was exploring bankruptcy did not come as a surprise. Rumours that the upscale department store chain was facing serious financial trouble have been swirling for many months. The tipping point was undoubtedly the 72 percent rent hike on its Madison Avenue flagship, which, as its top-performing brick-and-mortar location, accounts for a significant portion of the company's annual revenue.

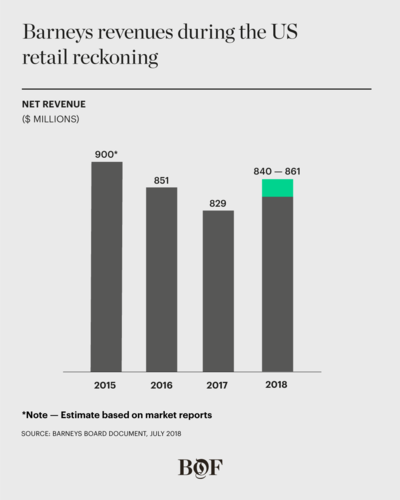

A report from a July 2018 board meeting, seen by BoF, paints a revealing picture of the financial realities facing the company even before the rent increase, which would significantly cut its EBITDA — or earnings before interest, taxation, depreciation and amortisation, a measure of operating profit.

ADVERTISEMENT

In 2017, Barneys generated a total $829 million in net revenue and $37.9 million in EBITDA. Management projected that sales would increase by 3 to 5 percent in 2018, and that in the best case scenario, EBITDA would be $39.9 million, a razor-thin operating profit margin of 4.6 percent.

In the four months between February 2018 and May 2018, sales were $263 million, up 2 percent from $258 million over the same period in 2017. However, management warned that while the first two months of the year were strong, sales had already started to “gradually deteriorate.” Sales at physical stores were almost $190 million, down 2.7 percent from the same period a year earlier.

Online sales, a bright spot for the retailer, were $65.7 million, up 19 percent year-over-year, though they missed projections of $72.6 million. And digital growth did little to lift the company’s overall performance. Slower growth in e-commerce sales meant the digital division delivered negative $2 million in EBITDA, versus a budgeted $4.4 million positive contribution to EBITDA.

Average order value (AOV) at Barneys.com was $254, down 6 percent year-over-year, and significantly lower than the AOV at its top-performing physical stores. (At the Madison Avenue flagship, AOV was $540; at the Beverly Hills store, it was $499.) And at off-price website Barneyswarehouse.com, average order value was only $153, down 19 percent from a year earlier.

By the end of May 2018, Barneys was in the red overall, with negative EBITDA of $2.7 million versus a budgeted positive EBITDA of $4.1 million, leaving little room for error — or the dramatic rent increase that would strike the following January.

When asked for further comment regarding these numbers, a spokesperson for Barneys said this information was private and out of date, declining to provide updated figures.

“Barneys is a strong business and we continue to see sales trends in line with our competitive set over the last 12 months,” the person said. “As with all businesses, we continue to evaluate our sales strategy and performance across all channels to ensure we are positioning Barneys for sustainable, long-term growth and success.”

And yet, Barneys' financial woes, combined with increased competition from multi-brand e-commerce sites and fundamental changes in the way people buy clothes — including the rise of direct-to-consumer retail and the blossoming of the second-hand luxury market — has meant that the retailer is perhaps no longer in a position to take as big of bets on emerging labels, the thing that long set it apart from competitors. (Many of which, including Neiman Marcus, have also suffered in recent years.)

ADVERTISEMENT

Instead of owning cool, Barneys began chasing it, much to the detriment of the store and many of the smaller labels whose brands and businesses it once cultivated.

Consider the case of Los Angeles-based Spinelli Kilcollin, a line that credits its early success as much to its relationship with Barneys as the distinctive tangle of linked diamond rings that it sells. In the fine jewellery market, Barneys has long been the go-to for emerging brands, which are often overshadowed at other department stores by enormous shop-in-shops occupied by the likes of Bulgari and Tiffany & Co. At Barneys, Spinelli Kilcollin had risen to become one of the top-five best-selling jewellery brands. Or at least that's what the brand was told in the autumn of 2018 when it started to consider dissolving its once-exclusive relationship with the store after concerns over late payments and a lack of marketing support.

In January 2019, when Spinelli Kilcollin exited the partnership and started selling to the store’s arch-rival, Neiman Marcus-owned Bergdorf Goodman, Barneys marked down Spinelli Kilcollin product by 15 percent before releasing the remaining pieces — which were sold on consignment — back to the owners. (Markdowns rarely happen to a jewellery brand in January or February.)

The brand’s contract with Barneys — signed in 2014, long before it was a significant business capable of negotiating better terms — allowed for this. But for a label that generates sales in the low double-digit millions of dollars per year, that’s a significant loss and can compromise relationships with other retail partners.

“The company is used to having people over the barrel,” said Michael Flanagan, Spinelli Kilcollin's financial advisor at the time, who viewed the move as a retaliation. “They try to pick you up early, throw you a decent amount, don’t let you go to anybody else and then, if you want to pull out, you’re going to give up 80 percent of your business. But that wasn’t the case with Spinelli. Barneys thought they had leverage, but they did not.”

Flanagan, who has advised numerous emerging brands over the years regarding their sales strategies, said he agreed to go on the record because he wants to act as a voice for designers who might not speak out against Barneys for fear of damaging their industry status.

The sentiment is not universally shared, however. When BoF asked Barneys for comment regarding the end of its partnership with Spinelli Kilcollin, a spokesperson responded with 12 testimonials from current brand partners, including jewellery designers Irene Neuwirth, Sharon Khazzam, Brooke Garber Neidich of Sidney Garber, Tate-owner Steve Messler and CVC Stones' Charles de Viel Castel, as well as Lipstick Queen founder Poppy King and consultant Nicola Guarna. The higher-profile designers who came forward included Narciso Rodriguez, Nili Lotan and Thom Browne.

“Barneys has always been a true partner...they have always supported me as a designer...and as a business,” Browne wrote in an email, sent via a Barneys public relations representative. “They have always supported the direction I have wanted to take my collections...and this has been very special to me as a designer.... I have been able to design collections without them asking why.”

Of course, it is in the interest of these designers for Barneys to survive, ideally landing in a better position than it is currently in.

Barneys continues to announce new partnerships with the bigger brands, including Chanel and Jil Sander, indicating that its top-tier customer remains engaged. However, finding young brands willing to sign strict exclusives with the retailer for at least one or two seasons, sometimes more, could become increasingly difficult.

Today, emerging labels have options, and many retailers dangle marketing opportunities in front of them in order to secure exclusives. (A placement in Net-a-Porter’s online publication, The Edit, can be a sales boon for lesser-known designers.)

“The system of traditional retail buying doesn’t work anymore,” a former Barneys employee said. (The individual requested not to be named because of a confidentiality agreement signed when still employed with the company.) “That’s why the business is suffering so much. There are so many new and innovative retailers. Brands would much rather be in Net-a-Porter than they would be in Barneys.”

Brands would much rather be in Net-a-Porter than they would be in Barneys.

Brands of all sizes also report late payments or being paid in unconventional ways, like with a credit card.

“We would have LVMH or L’Oréal put us on credit hold,” said one former buyer, who also asked not to be named because of a confidentiality agreement signed when employed with the company.

In response, a Barneys spokesperson said the store does not comment on individual contracts with partners, and that, “We have always had different types of payment programmes with our vendors – this is nothing new or uncommon.”

While a proportion of the tensions between Barneys and some of its brands may simply reflect wider problems with the wholesale model, the store is facing unique issues, too. But could these current challenges truly mark the end of Barneys New York?

Barneys has already survived multiple financial disruptions. In 1996, the company filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection. In 2007, a leveraged buyout created a heavy debt load. In 2012, the company implemented a major restructuring. There was also the equally disruptive image makeover, initiated in 2010 by former Gucci Chief Executive Mark Lee and his then-deputy, Daniella Vitale, who also worked with Lee at Gucci and became Barneys' chief executive in 2017 after his retirement.

Barneys New York on Madison Ave | Source: Getty

Lee and Vitale were criticised by some for zapping the much-loved quirk from the store's branding, visual merchandising and product mix as envisioned by former fashion director Julie Gilhart and creative director Simon Doonan. But they laid on a luxe, marbled look — for instance, swapping out the signature red awning in favour of austere black — which seemed to resonate with customers at the time. The makeover was largely funded by Perry, whose investment firm Perry Capital acquired a majority stake in Barneys in 2012 from Istithmar World PJSC in a debt-for-equity swap. (Perry Capital paid off Barneys' debt load in exchange for equity in the company.)

In a February 2016 interview with BoF, Lee said that EBITDA had more than doubled since he and Vitale arrived in 2010. Sales were approaching $900 million in 2015 and comparable store sales had increased each year since the beginning of their tenure.

It was in 2016 when competition got really tough. Along with digital challengers vying for customers, old-school competitors like Saks Fifth Avenue and Nordstrom were pouring money into their fashion programmes, sometimes offering better terms to brands in order to secure product exclusives. Indie labels were now launching via Instagram, and selling via their own websites. Then there were the independent retailers, including Dover Street Market and The Webster, which have managed to maintain a strong creative point of view despite financial pressures to conform and commodify.

Meanwhile, larger brands were increasingly focused on their direct-to-consumer channels. For instance, at Kering — the group that owns Gucci, Balenciaga and Saint Laurent — direct retail made up 77 percent of the group's income in 2018. The channel, which includes both e-commerce and physical stores, was up 31 percent overall in 2018.

These shifts affected Barneys’ business, like they did many of its direct competitors. On top of market headwinds, the retailer’s billionaire backer was beginning to get antsy. In September 2016, Perry — who once equated owning Barneys to owning the New York Yankees, according to a source — closed his hedge fund. This decision followed a failed attempt at raising funds from Silicon Valley venture capital firms that same summer, with the goal of turning Barneys into a real competitor to the likes of MatchesFashion and Farfetch. According to a person with first-hand knowledge of the efforts, investors were unimpressed with the amount of money Barneys had invested in its e-commerce experience and online acquisition compared to its $200 million investment in its physical retail network, in particular the opening of a five-floor, 58,000-square-foot downtown Manhattan store in Chelsea.

Part of the reason Barneys is so focused on brick-and-mortar stores is because that's where its customer is shopping. The retailer has found that its clients prefer to shop in-store — even its a millennial customer — so while digital is a part of the plan, it has not been the only focus. (About 60 percent of its “younger customer” spending happens in-store.)

However, even if Barneys is indeed making the right bet on physical retail, finding a buyer willing to invest further may be more challenging than ever.

If owning Barneys was once analogous to owning the Yankees, it’s now more like the New York Mets: once the untouchable, unbeatable gem, it’s now the team that just can’t catch a break. While there’s a chance an outlier like Amazon — which has long held luxury aspirations — may see Barneys as a deal, the crop of investors eager to help revive its outdated model is surely small.

In the case that the company does fail to find a backer and goes ahead with a bankruptcy filing, it doesn’t mean that it will immediately vanish. Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection does just that: it protects a business from creditors so that it doesn’t have to sell off its remaining inventory at rock-bottom prices while it restructures. In the unlikely scenario that it files for Chapter 7 bankruptcy, it will have to liquidate, although the retailer’s intellectual property may still be attractive to a buyer.

"It's a trophy asset," David Tawil, president of Maglan Capital, a hedge fund that focuses on distressed assets, told BoF earlier this year. "I don't think that any other operator is going to want to buy it. You have to get a foreign buyer… or someone very innovative."

Barneys is determined to keep moving forward. The retailer has new projects in the works, including a 50,000-square-foot store and Fred’s restaurant in New Jersey’s American Dream Mall, a $5 billion, 16-years-in-the-making development set to open this year. According to the internal board report viewed by BoF, the “New Jersey project” would be “fully subsidised by the prospective landlord.”

While a Barneys spokesperson declined to comment on the structure of the deal, she did outline several more initiatives underway, including the expansion of Freds, its popular restaurant, into more stores, as well as the opening of two new stores in Miami and Las Vegas and new locations of its cannabis lifestyle shop-in-shop, The High End.

But with the future of retail in flux, there’s no guarantee that Barneys will survive. Like many other great American fashion stores that have come before it — from Charivari to Henri Bendel to Marshall Fields — its time may simply have passed. It will be up to Barneys — and an enthusiastic new buyer — to prove that notion wrong.

Related Articles:

[ The Retail Apocalypse Is BackOpens in new window ]

[ Barneys Is Considering BankruptcyOpens in new window ]

[ How American Department Stores Plan to Fight Back in 2019Opens in new window ]

Antitrust enforcers said Tapestry’s acquisition of Capri would raise prices on handbags and accessories in the affordable luxury sector, harming consumers.

As a push to maximise sales of its popular Samba model starts to weigh on its desirability, the German sportswear giant is betting on other retro sneaker styles to tap surging demand for the 1980s ‘Terrace’ look. But fashion cycles come and go, cautions Andrea Felsted.

The rental platform saw its stock soar last week after predicting it would hit a key profitability metric this year. A new marketing push and more robust inventory are the key to unlocking elusive growth, CEO Jenn Hyman tells BoF.

Nordstrom, Tod’s and L’Occitane are all pushing for privatisation. Ultimately, their fate will not be determined by whether they are under the scrutiny of public investors.