The Business of Fashion

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

PARIS, France — Two days after Pierre-Yves Roussel sat down for a lengthy interview at the LVMH headquarters in Paris, his assistant telephones to say he would like to schedule a follow-up by phone.

As chairman and chief executive of LVMH Fashion Group, Roussel oversees a portfolio padded with a cross-section of covetable brands, including Givenchy, Céline, Marc Jacobs, Kenzo, Loewe, Pucci and, more recently, JW Anderson and Nicholas Kirkwood. Between our initial meeting and subsequent phone call, there has been a new development: Marc Jacobs International has announced the appointment of Sebastian Suhl to the position of CEO, effective September 2014. Suhl had previously held the same position at Givenchy.

To outsiders, the move might appear to be nothing more than a game of executive musical chairs. But Roussel, whom LVMH chairman and CEO Bernard Arnault wooed to the luxury conglomerate in 2004, insists that these "casting" decisions are infinitely more complex. For one thing, he must carefully consider the dynamic between the brand's CEO and its creative director, Marc Jacobs. While both report to Roussel, they must also be able to operate as a self-contained duo.

Roussel’s multi-faceted job description is not limited to casting the right combination of CEO and creative director, however. It also requires overseeing an increasingly complex global value chain, encompassing tightly knit functions across design, product development, merchandising and retail. Just consider the rapid rebooting and expansion of Givenchy, Céline and Kenzo and you can begin to appreciate the far-reaching impact he has made in a short time.

ADVERTISEMENT

How someone with such influence has managed to maintain a largely low-key public persona reflects a discreet leadership style that is equal parts decisive and deferential. Most importantly, he leverages trust in human capital to achieve results. Or, to hear Roussel reduce his role to two main tenets, “We make [our] brands resonate and we make people successful.”

When both occur in tandem, the results can be impressive. While LVMH does not report figures on individual fashion brands, market sources estimate that 2013 revenues for Roussel’s top brands, Marc Jacobs International and Céline, were nearly $1 billion and $700 million respectively.

“What I did seven or eight years ago was to push each brand to be very clear on something that they really did well and not try to be everything for everyone,” he explains in a nondescript conference room in the LVMH offices on the upscale Avenue Montaigne. “I didn’t look at the market and say, ‘We have to cover this segment or that segment.’ I just started with the portfolio and I kept all of them. We didn’t sell any brands because they were all incredibly powerful.”

Raised in Paris, Roussel is fluent in English and converses with the no-nonsense confidence of a business leader (though he defaults to second- person "you" or the collective "we" rather than the more assertive first-person). He wears Berluti shoes, ties from Givenchy or Dior Homme, and bespoke suits in Loro Piana fabric. Next year, Roussel will turn 50, yet he could fool anyone into believing he is a full decade younger. His inner circle respectfully refers to him by his initials, PYR, conferring a hotshot aura that he deflects but has rightfully earned.

Roussel has managed LVMH's fashion brands in a group separate from the conglomerate's cash cow Louis Vuitton since Arnault created the position for him in 2006. Back then, Riccardo Tisci had only just joined Givenchy. Then, shortly thereafter, under Roussel's oversight, Stuart Vevers would take the reins at Loewe, Phoebe Philo would make the move to Céline and, taking the industry by surprise, Opening Ceremony's Carol Lim and Humberto Leon were tasked with repositioning and re-envisioning Kenzo. Last year, after Vevers' abrupt departure to Coach, Roussel hired Jonathan Anderson to take his own shot at rebooting Loewe, which had failed to take off under Vevers.

Roussel entered the fashion industry as an outsider. After earning his undergraduate degree in economics at the École Supérieure de Commerce in Paris, he began working at Crédit Commercial de France (now HSBC) in Brussels while completing a post-graduate degree at Brussels University. Roussel later attended The Wharton School, where he completed an MBA. Upon graduation in 1993, he joined management consulting firm McKinsey & Company, which took him to New York, Hong Kong and Tokyo. When he settled at McKinsey's Paris office, he specialised in consumer industries, including luxury goods, and was elected partner in 1998 and senior partner in 2004.

Roussel was someone who could provide strategic and operational insights; his strengths in identifying efficiencies and establishing best practices were put to use years before he began to take on the responsibility of reconfiguring brands and casting their leaders. “You can have a great product, but if it comes into the store five weeks too late, forget it, you don’t give a chance to the product,” he explains.

“If it’s overpriced or if the quality is not there, you’re not giving justice to the potential of the creative talent.” Roussel found himself spending more time with the creative talent in their ateliers, accompanying them to factories or attending their fashion shows. This, he says, was enlightening. “You begin to understand how you transform a sketch to a prototype and a prototype to a real product.”

ADVERTISEMENT

Pierre-Yves Roussel and Sebastian Suhl | Photo: Michel Dufour/WireImage

Over the years, Roussel has quietly built a wide and influential network within the broader fashion ecosystem. Beyond the world of LVMH, he reached out to influential figures across the industry — including Suzy Menkes, Carine Roitfeld and Anna Wintour — who shared with Roussel their impressions of the designer talent pool. And, gradually, with no pretense of being an expert, his sense for creatives started to catch up with his sense for operations.

“He’s very discreet and he’s not pushy and he listens and he understands,” says Wintour, artistic director of Condé Nast and editor-in-chief of American Vogue, of Roussel’s relationships with designers. “He’s a confident man himself, and that gives confidence to the designers that he’s working with. They sense that he understands their world.”

“In today’s world you can’t really have a successful brand without a strong relationship between the designer and the business side. It just doesn’t work,” continues Wintour. “As a designer, if you know the support is there, and the interference isn’t, that’s sort of a magic combination.”

“[Designers] are so intuitive; they feel everything. So if you try to be smarter than they are, it just doesn’t work,” says Roussel. “The best is to be who you are; there are things you know and other things you have no clue. But if, at the end, you don’t produce and don’t deliver and don’t provide the machine for them to express their creativity, it just doesn’t happen.”

Roussel also notes the importance of having both broad strategic perspective and sharp critical focus; still using some of his consultant speak, he dubs this the “helicopter” view.

“I think the real great talent in our industry — and this is true for creative people as for management — is the ability to see the big picture and be very micro,” he says. “It is very simple to explain; it is very difficult to execute,” he adds. “I could have told you ten years ago what is necessary to make a great designer or CEO. And it’s still true. But now I know what it takes to do it.And a lot is about judgment and judgment is about experience.”

Roussel makes clear that a decade of significant transformation does not come without significant capital investment. “I have never had the discussion with Mr Arnault, ‘If you do this, you cannot do that,”’ he says. “So there’s never this kind of arbitrage based on limited resources. It’s not like I get an allocation that I’m allowed to spend for the next few years and then I need to make arbitrage between portfolio projects. The more successful projects you have, the more resources you get to make them work.”

ADVERTISEMENT

With Kenzo, specifically, he says the arrival of Lim and Leon (not long after the appointment of CEO Eric Marechalle) at the newly repositioned Kenzo generated so much excitement — internally and from the public — that increased investment proved a no-brainer.

“I think he was very interested in our way of looking at a brand and celebrating history in a way that felt like it was moving into the future — that we weren’t just being nostalgic but giving modernity to something,” says Leon, adding that Roussel has always appeared interested in the creative side of the brand, supporting their collaborations with Jean-Paul Goude and edgy arts magazine Toiletpaper. “The most exciting thing about him is he loves looking at us and what we stand for and what we’re good at and making sure that our voice could be heard through the brand, which is rare. Aside from that, he is very curious and involved in the product and he’ll give exact expertise in product categories.” Exane BNP Paribas estimates Kenzo’s 2013 revenue at €100 million (about $130 million).

Pierre-Yves Roussel and Riccardo Tisci | Photo: Bertrand Rindoff Petroff/Getty

Despite solid results, the Fashion Group’s combined portfolio only represents somewhere between 3 to 5 percent of LVMH’s overall profits, according to Luca Solca, head of luxury goods at Exane BNP Paribas, underlining that growth remains top priority for Roussel, who acknowledges that growing a fashion business requires time and effort.

“Sometimes, it takes as much time to help to grow a small brand into a big one as to make a medium size into a larger one. And you usually learn the challenges at every single stage,” he says. “Even within a big brand, you have start-ups.”

Following the group’s investments in JW Anderson and Nicholas Kirkwood, Roussel created an incubator team that devotes its energy to supporting the group’s smaller brands.

Jonathan Anderson says the support is invaluable. “Something like this, you can’t put money on; you can only get from years and years of experience,” he explains, adding that Roussel challenges and inspires him to think more broadly about business considerations. Anderson also notes how Roussel seems equally engaged in his namesake brand as well as Loewe, of which the designer is creative director. “I think it’s remarkable how I always feel like he’s there — on both brands, even though one is a lot bigger than the other,” says Anderson.

Once a brand finds its footing, Roussel remains engaged; after all, he remains the chairman of every brand in his portfolio and occasionally plays a more active role when a project may be in flux. Even if Céline’s CEO Marco Gobetti or Loewe’s Lisa Montague check in every week, there is an ongoing “grooming” relationship, he says.

“We are not an industry of followers. And as the leader of the industry, we are leaders by construction. But the fashion industry is an industry of leadership... and we have to lead from the forefront, not from behind,” he continues. “So my role is actually to make as many leaders we can in all the positions that are critical to any of our brands — and making sure that diversity of brands and talent work together.”

It helps that Roussel has such direct access to Arnault — reporting to him, yes, but also guided by him. For their weekly meetings, Roussel, whose office is on the eighth floor, will typically head up to Arnault’s office on the ninth floor. As Roussel tells it, they discuss “every single important decision” but that trust underlies everything. “I don’t make any crazy decisions but we take risks,” he says, by way of underscoring Arnault’s confidence in him. “The group works by delegation, too, so Mr Arnault has to trust me as I have to trust the judgment of the CEOs.”

Roussel insists that exceptional business leaders are as rare as exceptional creatives. This can be attributed, at least in part, to the reality that executives specialising in the luxury realm are a relatively recent development. Christian Dior Couture's Sidney Toledano worked at Lancel before being handpicked by Arnault in 1993.

Yves Carcelle also lacked luxury experience when he became CEO of Louis Vuitton in 1990. “Now we have a younger generation who can learn from within,” he says. “I think being able to groom, coach and develop people is actually the ultimate competitive strength or weapon... and this is true for designers as well.”

“The real synergy of the group is the expertise we have. There’s always someone who knows something about whatever subject,” he adds. “The question is, ‘Who is that person and how can you get to their strengths and make those connections happen so you learn faster, move faster and smarter than others?”

Disclosure: LVMH is part of a consortium of investors which has a minority stake in The Business of Fashion.

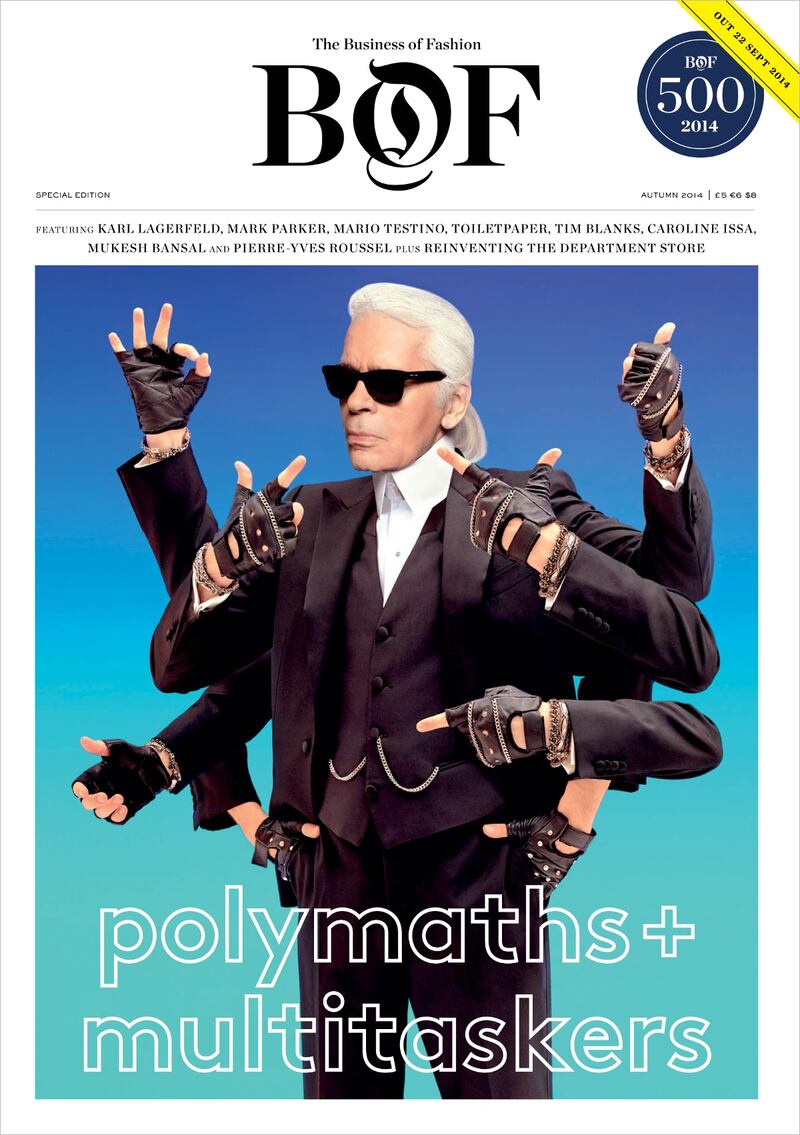

This article originally appeared in the second annual #BoF500 print edition, 'Polymaths & Multitaskers.' For a full list of stockists or to order copies for delivery anywhere in the world visit shop.businessoffashion.com.

Cover of the BoF 500 ‘Polymaths & Multitaskers’ Special Print Edition

Nordstrom, Tod’s and L’Occitane are all pushing for privatisation. Ultimately, their fate will not be determined by whether they are under the scrutiny of public investors.

The company is in talks with potential investors after filing for insolvency in Europe and closing its US stores. Insiders say efforts to restore the brand to its 1980s heyday clashed with its owners’ desire to quickly juice sales in order to attract a buyer.

The humble trainer, once the reserve of football fans, Britpop kids and the odd skateboarder, has become as ubiquitous as battered Converse All Stars in the 00s indie sleaze years.

Manhattanites had little love for the $25 billion megaproject when it opened five years ago (the pandemic lockdowns didn't help, either). But a constantly shifting mix of stores, restaurants and experiences is now drawing large numbers of both locals and tourists.