The Business of Fashion

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

NEW YORK, United States — If the ability to throw a 100-mile- per-hour fastball sits at one end of the human-capital spectrum, stocking shelves and swiping bar codes is at the opposite. But the U.S. economy gets on quite nicely with just a few dozen ace pitchers, while it takes vast stadiums of cashiers—and no small amount of investment in human capital—to keep things humming.

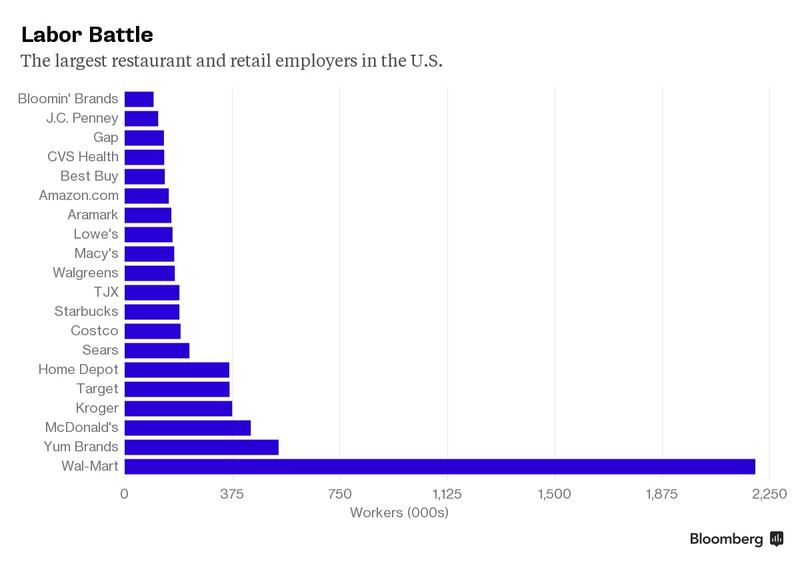

A modest bidding war has broken out among the retailers who hire from the bottom of the labor pool, buoyed in part by improving sales. Wal-Mart moved to raise the pay for its lowest-level workers to at least $9 an hour, a decision quickly matched by TJX, the parent company of TJ Maxx and Marshalls. Gap, Starbucks, and IKEA had already joined the growing list of service sectors now committed to higher starting wages, with tens of thousands of low-paid workers affected by recent changes.

These rising wages are sure to be costly for employers: Walmart, for example, warned that its mass raise would chew up an additional $1 billion a year, a figure that spooked investors and drove down the company's share price. From a labor-market perspective, meanwhile, the U.S. economy would still appear to have plenty of would-be cashiers and clerks sitting on the sidelines. The 5.7 percent jobless rate rose slightly last month because more idle workers started looking for jobs.

So why are these big employers risking the wrath of investors by forking over more money to their least-valuable employees? Better wages can be understood, in part, as an effort to keep workers from leaving—or at least leaving quite so soon. “It's hard to see, on a general basis, that this is from a lack of people," says David Branchflower, an economics professor at Dartmouth University. "But let's say it costs you two days to train people and they stay for six weeks. If they stay for 12 weeks, you’ve halved the cost of training.”

ADVERTISEMENT

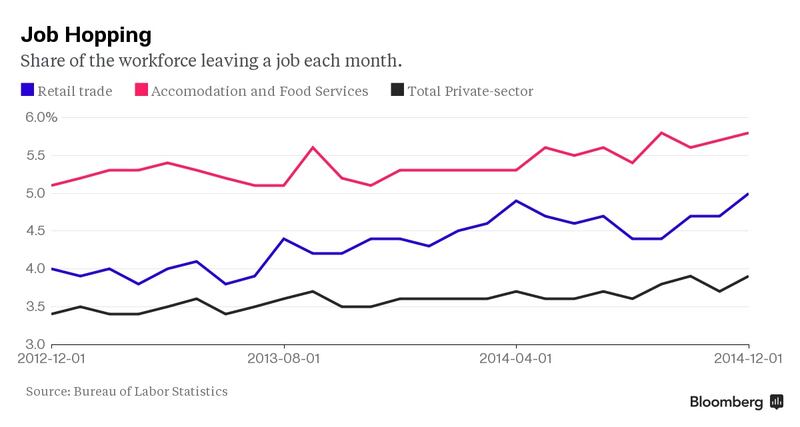

Turnover in the retail sector has been steadily rising and now stands 5 percent a month. At that rate, if Walmart's workforce were to hold to the national average, over a full year it would be losing 60 percent of its sales staff. Employee churn at fast-food chains is even worse: Almost 6 percent of all fast-food workers left or were laid off in December, according to federal data. An individual worker won't ever command anything like the salary-bargaining powers of a baseball player, of course, but service economy employers tend to notice a rising tide of worker defections. Plugging all those gaps in the workforce is hugely expensive.

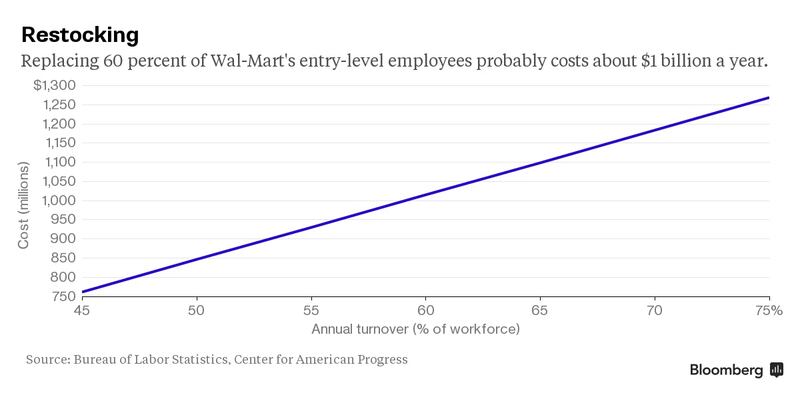

Here’s how the math breaks down:

That adds up quickly. Walmart has about 500,000 low-wage employees. The cost of replacing each one, using the rough estimate from above, comes to roughly $1 billion—the cost of the just-announced wage increase to $9 per hour.

Boosting wages at the bottom won’t stop turnover entirely, but it can help reduce training and recruitment costs. Giant retailers also have to consider intangibles. New workers, for example, generally aren’t as productive as seasoned employees, creating an efficiency cost that goes beyond the expense of finding and training a rookie. Plus, many retailers—Walmart in particular—have long paid a reputational cost for poor pay.

The cost of training new employees varies widely. Take Uniqlo, the massive Japanese apparel retailer that is ndergoing a rapid expansion in the U.S. and claims to pay wages in the top 25 percent of the industry. New workers go through a two-week training process that includes memorization of rote phrases to be used in customer interactions. Uniqlo's salesforce learns how to handle clothes, the proper way to hang garments on racks, and nuanced behaviors governing everything from posture to the correct way to hand a credit card back to a shopper. Before training is complete, each new worker must pass a letter-graded folding test.

Uniqlo USA Chief Executive Larry Meyer thinks about employee retention all the time, he says, since there's a "high cost of losing that talent" once the company has invested in training. Plus, he notes, Uniqlo counts on keeping veterans around to teach the rookies. Workers can continue taking training courses that cover such topics as how to better run a register or techniques for improved folding. "We feel we have to enrich them," says Meyer, breaking it down into a simple equation. "If people are happy, the retention rate is high. If not, the retention rate is low."

Some retailers have long been out to prove that front-line workers can make higher salaries without sapping profits. Workers at the Container Store earn $48,000 a year on average—about twice the industry average—and the company enjoys a 10 percent annual turnover rate, which is extremely low for a retailer. At Costco, meanwhile, the average hourly worker starts at $11.50 and those who stay for more than five years can make more than $20 per hour. “This is not altruistic,” Costco co-founder Jim Sinegal said of his company's pay practices. “This is good business.”

The retailers that recently elevated their low-end wages seem to have that same rationale: Pay workers more, make them happier, and keep them from leaving. “We think it’s absolutely imperative that we keep pace and that we have the best talent,” said Carol Meyrowitz, chief executive officer of TJX, on a conference call after announcing the raise. Walmart CEO Doug McMillon likewise stressed the importance of providing a ladder for workers to climb: "As important as a starting wage is, what’s even more important is opportunity," he wrote in a letter to employees. In a similar missive to his army of baristas, Starbucks Chief Operating Officer Troy Alstead wrote, "The new rates will ensure we are paying a competitive wage that better positions us to attract and keep the best partners."

ADVERTISEMENT

Gap, which is bumping its minimum wage to $10 an hour this year, has seen a double-digit percentage increase in job applicants since it made the announcement a year ago, according to Dan Henkle, senior vice president of human resources at the apparel retailer. "Attracting top retail talent is incredibly competitive," he says. Many of his employees cite the wage hike decision as "a reason to build a career" at Gap, Henkle adds, even among workers unaffected by the change.

Some of the biggest retailers in the U.S. haven't budged on pay—most notably Target, which made it clear last week that raises aren't on the horizon. But as more retailers ratchet up their lowest hourly wages to $9 or more, it will become tougher to reduce employee turnover with pay alone. If retailers really want to reduce churn, the next frontier will probably be promising more predictable schedules, rather than higher wages. Indeed, Walmart says that early next year it will begin offering fixed schedules 2.5 weeks in advance. "We wanted to give them more control and more predictability or flexibility for those that need it," said Walmart spokesman Kory Lundberg.

Fixed schedules don't come cheap either. They require improved forecasting of shopping traffic, worker-absentee patterns, even weather—and the data scientists that can whip up that kind of operational wizardry make a lot more than $9 an hour.

Blanchflower, the Dartmouth economist, points to surveys that find most retail employees are happy to work longer hours for the same wage, providing they get more predictable hours. “These are absolutely crap jobs,” he says. “You can’t make the jobs not crap, but you can make them less crap by giving people more security.”

By Kyle Stock, Kim Bhasin; editor: Aaron Rutkoff.

The rental platform saw its stock soar last week after predicting it would hit a key profitability metric this year. A new marketing push and more robust inventory are the key to unlocking elusive growth, CEO Jenn Hyman tells BoF.

Nordstrom, Tod’s and L’Occitane are all pushing for privatisation. Ultimately, their fate will not be determined by whether they are under the scrutiny of public investors.

The company is in talks with potential investors after filing for insolvency in Europe and closing its US stores. Insiders say efforts to restore the brand to its 1980s heyday clashed with its owners’ desire to quickly juice sales in order to attract a buyer.

The humble trainer, once the reserve of football fans, Britpop kids and the odd skateboarder, has become as ubiquitous as battered Converse All Stars in the 00s indie sleaze years.