The Business of Fashion

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

Before the pandemic, the emerging consensus was that fashion’s last wave of initial public offerings was a bit of a bust. But as e-commerce sales soared over the past year, so did the stocks of public companies like Farfetch and Stitch Fix. Their share prices are trading at near-record highs.

Now, a new group of start-ups want in.

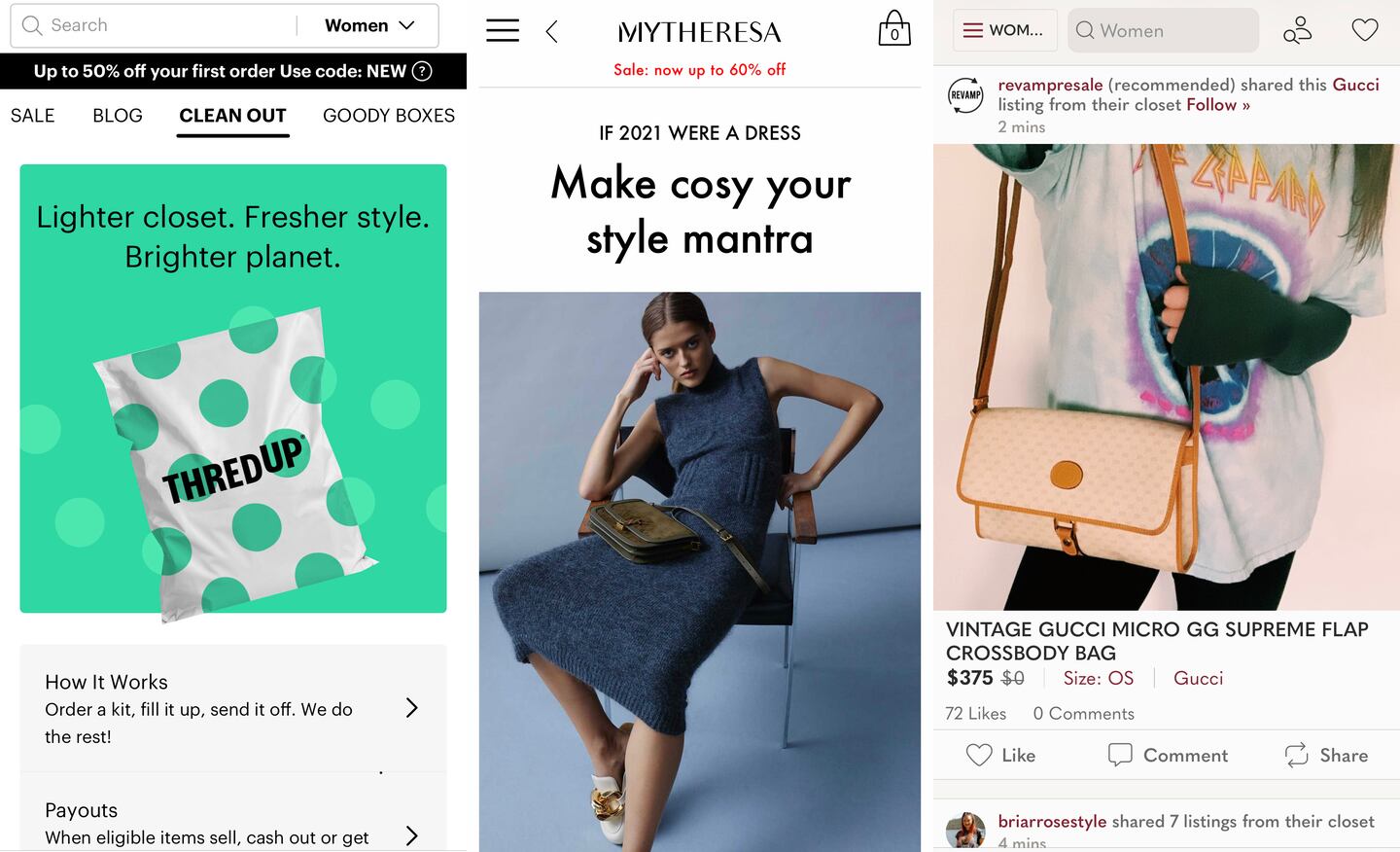

Online luxury retailer Mytheresa, peer-to-peer reseller Poshmark and mass-market reseller ThredUp — as well as online payments system Affirm — are planning to go public in the coming weeks. Poshmark is planning to price its IPO later this week. On Monday, British shoe brand Dr. Martens, owned by private equity firm Permira, said it was considering an IPO in London this year.

While these companies all boast different value propositions, they have plenty in common. They face well-capitalised challengers in crowded categories, and they’ve previously raised significant funding from private investors. Where in the past new money may have come from additional funding — or a sale — few cash-rich strategic buyers have shown interest in acquiring e-commerce platforms, for instance, and going public can offer a level of liquidity that a private investment may not.

ADVERTISEMENT

However, an IPO also sets them up for public scrutiny and additional regulations, which can be a disadvantage during difficult business periods. While these companies can likely expect their share prices to pop at the opening bell on the first day of trading, the mixed record on recent fashion and retail IPOs signals a challenging road ahead.

BoF spoke to analysts about what to expect from three of this year’s most-anticipated IPOs.

Mytheresa

What is it? Online luxury retailer Mytheresa started as an upscale store in Munich in 1987, launching its e-commerce operation in 2006. It competes against Net-a-Porter, MatchesFashion, Farfetch and other multi-brand retailers selling luxury goods online. Mytheresa was sold to the Neiman Marcus Group in 2014 but was independently operated. (It is now owned by NMG’s private equity investors and also its creditors.)

Why go public now? With over $500 million in annual sales in the year ending June 30, up 20 percent from a year earlier, and an average order value of $674 — one of the highest in its competitive set — the profitable business benefited from a boom in pandemic-era online shopping. While it was seen earlier in the year as an acquisition target for a strategic group, a public listing in a market bullish on online retailers may offer a bigger return to previous investors. While its plan is to raise up to $150 million, a strong debut could value the global retailer at over $1 billion.

A year ago, the idea of a luxury e-commerce site going public would feel precarious, given Farfetch’s uneven performance and the well-documented struggles of private companies in the sector, including Yoox Net-a-Porter Group, Moda Operandi and MatchesFashion. However, the pandemic boosted sales at Farfetch, which projected it would finally reach profitability in the last quarter of 2020. Farfetch also entered a joint venture with Chinese internet giant Alibaba and Swiss conglomerate Richemont, raising $1.15 billion in additional funding.

The luxury marketplace’s stock soared, currently trading at $60.47 per share, up 440 percent from $11.15 a year ago.

“As we have seen with Farfetch, for example, Covid-19 has provided a major boost and growth acceleration,” said Luca Solca, a luxury analyst at Bernstein. “This may be a way to make hay while the sun shines.”

ADVERTISEMENT

What do investors need to know? Mytheresa prides itself on its steady approach to increasing sales. Instead of sacrificing profitability for explosive growth — its customer acquisition costs fell by nearly 10 percent in the last fiscal year — it has differentiated itself through unique product and a focus on high-touch customer service. Of the 7,000 unique styles it had on hand in December 2019, just 21 percent overlapped with competitors, according to an internal review.

And according to its registration with the SEC, the site claims a net promoter score, a measurement of online customer satisfaction, of 83 — extremely high for an online apparel retailer, or any retailer for that matter. The site’s customer base has grown at a compound annual rate of 29.7 percent since fiscal 2016. Shoppers tend to come back over and over: more than 65 percent of net sales in its latest fiscal year came from customers who had shopped with Mytheresa in the past.

Analysts value Mytheresa’s one-to-one approach to customer service. “I like the original curation that Mytheresa has been able to develop,” Solca said. “This makes me [confident] about their ability to stand their ground and make a profit.”

The question, of course, is how big Mytheresa can get in a highly competitive market with only a certain amount of covetable product. Exclusive styles only work if they are what the customer wants, and as more brands take an increasing amount of their business direct, Mytheresa and its team will have to campaign hard to be the wholesaler of choice.

Poshmark

What is it? Founded in 2011, Poshmark is one of the biggest secondhand e-commerce shops in the US and Canada with nearly 32 million active users as of last September. It’s a peer-to-peer marketplace, which means that the company doesn’t carry inventory, unlike resale competitor ThredUp or The RealReal, which procure clothes from sellers on consignment, taking a percentage of the revenue when the item is eventually sold.

Why go public now? So far, The RealReal is the only major apparel resale player in the public market — eBay and Etsy are less specialised — but the growth potential for the sector is projected to be colossal. A recent Cowen & Co. report estimated that the “re-commerce market,” which includes resale and rental, could reach 14 percent of the total fashion market in 2020, up from a 7 percent share in 2019. Analysts believe that resale’s share of the apparel sales market will only continue to increase.

What do investors need to know? Poshmark specialises in a much lower price point than The RealReal, with an average order value of $33. It has already achieved profitability, in part thanks to its no-inventory model. Its first profitable quarter came in the three months ending June 30, according to its registration statement. In the four quarters ending on September 30, 2020, Poshmark posted sales of $247.5 million and adjusted EBITDA (earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation) of $17.5 million. Its gross merchandise value — or the cost of goods sold on the site — totaled $1.3 billion in that same period, compared to $1 billion the previous year.

ADVERTISEMENT

“The marketplace model allows for the consumer and seller to absorb a lot of the expenses that otherwise burden the company in a consignment model,” said Simeon Siegel, retail analyst and managing director at BMO Capital Markets.

Investors may also appreciate Poshmark’s simplified fee model. The company charges a 20 percent fee for any transactions $15 or above and a $2.95 flat rate for all cheaper items, offering one of the most attractive and consistent commission rates on the market.

One of Poshmark’s calling cards is that its app also doubles as a social network, which it says helps to increase usage and engagement. Users not only buy and sell from one another but also engage in interactions through comments, shares, follows and negotiations on purchases.

While Poshmark will soon become one of the few mass-market resale players on the public market, competition in the space is heating up. In the US, Poshmark is already competing with ThredUp, eBay, Depop and a new crop of resale marketplaces, including Mercari.

Some users have criticised Poshmark’s intense selling process, which requires regular engagement with other users to make sales. The company’s wholesale division, under which it sells private label inventory in bulk to some users, has also come under scrutiny as sellers cite issues with offloading the inventory after committing to selling it. The wholesale programme generated less than 1 percent of Poshmark’s gross merchandise value in 2019.

ThredUp

What Is it? Founded in 2009, ThredUp is a resale consignment website that offers shoppers millions of secondhand apparel products from brands like J.Crew and Ann Taylor at a fraction of the retail cost. Dubbed the “modern Goodwill,” its website touts pricing that starts at $7 for sweatshirts and $10 for leggings.

Whereas Poshmark markets itself as a way for sellers to set up a lucrative business, ThredUp’s value proposition is that consumers can get rid of a lot of stuff at once. Sellers can request free “Clean Out Kits,” which include a prepaid shipping label, and send back the kits filled with their unwanted garments.

ThredUp confidentially filed for an IPO in October, and its registration statement remains private. The company has yet to disclose the size and price range of the offering.

Why go public now? Like Poshmark, ThredUp sees tremendous opportunity in a swiftly growing resale market. Its low prices on the buyer side make it a high-volume business, while the ease of use on the seller side all-but guarantees a steady supply of fresh goods.

When ThredUp raised its last round of private funding in 2019, the company said it intended to use the capital for expanding its digital infrastructure and growing its retail partnerships arm with brands including Madewell, Gap, Walmart and Macy’s. These partnerships vary case-by case. Some allow retailers to sell secondhand products provided by ThredUp at select locations, while others offer their customers ThredUp’s clean out kits in exchange for store credit for any sold items.

ThredUp is among the few resale platforms to offer secondhand commerce as a third-party service. It competes with Trove, which sets up resale channels for retailers and brands.

With an IPO, ThredUp will be able to gain significant market share in the “resale-as-a-service” space, in addition to gaining further mindshare among consumers.

What do investors need to know?

While ThredUp makes its selling process easy for consumers, it ends up doing all the heavy lifting of sifting through, photographing and listing items itself, which likely weighs down its profits. This continues to be a problem for The RealReal as well, which went public in 2019 and has yet to become profitable.

ThredUp’s commission rates are also high: items priced below $20 have a payout rate of 3 to 15 percent for the seller.

Like Poshmark, ThredUp competes with Depop and Lithuanian peer-to-peer resale website Vinted, both of which recently raised private funding for expansion plans.

Investors say one of ThredUp’s biggest strengths is its burgeoning retail partnerships division. ThredUp is able to convince brands, who are largely wary of the secondhand market, to embrace resale. The idea is that by encouraging customers to resell a used handbag or dress, they then will have the cash to spend on the primary market. In the case of Reformation’s partnership with ThredUp, for instance, shoppers get store credit for any of the items they sell through the resale platform.

“Retail historically is a zero-sum, but resale doesn’t have to be,” Siegel said. “It will naturally syphon away some dollars from the [traditional retailers] but...it will also be a new way to free up the customer’s wallet to buy something else.”

Related Articles:

Why Is Everyone Betting on Farfetch?

The Future of Resale: 5 Key Questions

The Problem With the Online Luxury Model

The app, owned by TikTok parent company ByteDance, has been promising to help emerging US labels get started selling in China at the same time that TikTok stares down a ban by the US for its ties to China.

Zero10 offers digital solutions through AR mirrors, leveraged in-store and in window displays, to brands like Tommy Hilfiger and Coach. Co-founder and CEO George Yashin discusses the latest advancements in AR and how fashion companies can leverage the technology to boost consumer experiences via retail touchpoints and brand experiences.

Four years ago, when the Trump administration threatened to ban TikTok in the US, its Chinese parent company ByteDance Ltd. worked out a preliminary deal to sell the short video app’s business. Not this time.

Brands are using them for design tasks, in their marketing, on their e-commerce sites and in augmented-reality experiences such as virtual try-on, with more applications still emerging.