The Business of Fashion

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

Get the essential tools, templates and frameworks for successful entrepreneurship at BoF’s Start-Up School.

DOMAT, Switzerland — Rinaldo Willy is one of the most intriguing entrepreneurs in the gem trade, but you won't find him air-kissing clients or toasting a sale at one of Geneva's glamorous jewellery fairs. The big brands of the industry don't want to mingle with him and — although he's too gracious to say so — the feeling is mutual.

Bombarded with orders from across the globe, Willy is at an important crossroads in his bizarre yet emblematic entrepreneurial journey. While his business is modest compared with giants like Cartier, his clients are emotionally invested and loyal to a degree that would make any big-brand executive envious.

Most of his customers place orders through agents in well-heeled districts of cities, from Houston to Singapore. Some, however, refuse to confirm their orders until they meet Willy face to face. A proposition as unique as his raises so many questions that they need to see it to believe it.

ADVERTISEMENT

Listen to this article:

A pilgrimage to Willy’s state-of-the-art facility brings you 120 kilometres outside Zurich — one wrong turn and you’re in drowsy Liechtenstein. Beyond the glacier and past a dairy farm or two, the town of Domat gradually comes into view. The Alpine setting oozes so much syrupy charm that you almost expect Julie Andrews to waltz out from behind a chalet. But upon entering the solemn halls of Willy’s headquarters, things take a sharp turn. It is more like a futuristic funeral parlour than a showroom selling sparkle — and for good reason.

Willy and his team at Algordanza are in the high-tech business of transforming cremation ashes into diamonds — many of which end up being made into rings, pendants and other fine jewellery items, worn by mourning widows or loved ones of the deceased. Awkward, but lucrative. “Let me show you where they turn dead people into diamonds,” is how one local teenager introduces new kids to the town. But Willy isn’t vexed. He knows the score.

Taboo, but it's a topic that everyone needs to talk about at some point

“Anything to do with death is a taboo topic in most countries and there are many unspoken rules in every culture,” says Willy, nodding to his technician in a lab coat whose subdued body language isn’t too far off from a kindly undertaker. “Taboo, but it’s a topic that everyone needs to talk about at some point.”

To dismiss Rinaldo Willy as an eccentric with an unhealthy fascination for the macabre would be wrong. It would also miss the point. The product created by Algordanza may make you flinch, shed a tear of joy or even repulse you, but the business model behind it is thoroughly modern.

Much like lab-grown leather maker Modern Meadow and synthetic spider silk producer Bolt Threads, Algordanza is a fashion-tech hybrid that breaks down the walls that once divided industries, allowing the kind of cross-pollinated ideas that can give rise to powerful, persuasive new business concepts.

When Willy founded Algordanza fifteen years ago, he married the rock-solid certainty of the death industry with the vagaries of the jewellery market, by leaning on science and technology to reimagine the conventional keepsake. Calling his concept “innovative” would be an understatement.

Innovation is such an overworked buzzword that it is easy to lose sight of the bigger picture. It is no coincidence that Willy’s native Switzerland was named the world’s most innovative country in 2018 by the World Intellectual Property Organization — a crown that it has kept for eight years in a row. It continues to outrank more than 120 economies, based on a collection of 80 performance indicators.

ADVERTISEMENT

But entrepreneurship isn’t defined by innovation alone. The research and development behind Willy’s business would be meaningless if the brand weren’t so emotionally poignant. Just ask Algordanza customer Arja Tytti Rauramo-Kvam, a Swedish-Finnish widow who had been married to her husband for 35 years before he died of cancer.

I was never a big networker, but I was a spin doctor — all those shock shows, that's how I got my first [financial] backers

“One of my friends asked me, ‘Are you sure it’s not some kind of scam?’” she recalls. “But the way they treated me [was] with such respect and dignity and compassion, and so much time and consideration. Plus, I also got certificates and gemmological proof of wavelengths mapping the diamond structure. Somehow the diamond is faintly blue, but my husband had blue eyes, so I don’t mind.” She trails off, weeping.

“I don’t care what anybody thinks, to me it was wonderful. When I took the diamond to the jeweller to set into something, I said, ‘How can I trust you? This is my husband we’re talking about. I don’t want to let this diamond out of my sight.’ But I did and now I wear it every day. He was my first love and my only love. Now I have him with me, always.”

Heavy stuff — but heavy stuff from a very satisfied customer. To be sure, the jewellery establishment still dismisses Willy as a weirdo or an interloper, but even his critics begrudgingly praise his entrepreneurial flair. He is a trailblazing figure nonetheless.

For decades, designer-entrepreneurs were the lifeblood of the fashion industry. Sometimes they were secretive virtuosos like Antwerp's Martin Margiela, or emotional enfants terribles like self-described "East End yob" Alexander McQueen. Back in 2003, just three years after Gucci Group acquired 51 percent of McQueen's brand in a deal that gave him full artistic license, he took part in a blunt interview with Polly Vernon that seemed to sum up the entrepreneurial spirit of his generation. "I was never a big networker," he said, "but I was a spin doctor — all those shock shows, that's how I got my first [financial] backers."

Alexander McQueen Ready-to-Wear Autumn/Winter 2009 fashion show in Paris | Source: Getty Images

These days fashion entrepreneurship is more likely to take the form of cleverly positioned — but spiritless — internet brands, founded by a polished guild of MBAs with fully rehearsed elevator pitches, fluent in the language of MVPs and venture capital, and eager to pivot. “When speaking to colleagues within the fashion world, there’s this tension that’s perceived between the use of data and creating emotional responses,” says Warby Parker co-founder Neil Blumenthal. “I think that’s misplaced.” Nevertheless, these two waves of entrepreneurs are different — in part, at least — because they have been educated in very different ways.

Ten years ago, the Kauffman Foundation released its seminal report, “The Anatomy of an Entrepreneur,” which surveyed over 500 American company founders across a wide range of industry sectors. The results confirmed what everyone already knew — there is a strong link between entrepreneurship and higher education. The surprise was just how much they were correlated. Over 95 percent of the surveyed entrepreneurs had bachelor‘s degrees, and 47 percent had more advanced degrees.

ADVERTISEMENT

It is true that Steve Jobs and Mark Zuckerberg didn't finish university and designer drop-outs like Michael Kors and Alexander Wang demonstrate that you don't need a degree to build a business. Yet a casual look at the CVs of the founders of some of the most in-demand designer brands indicates that degrees from top fashion schools in New York, London or Paris still matter.

Meanwhile, a debate is raging about whether even the best schools are managing to keep up with the latest business and tech training that aspiring fashion entrepreneurs need to launch successful start-ups. Elsewhere, the situation is more dire. “Education is a major problem [for] fashion entrepreneurship,” says Alexander Shumsky, president of Mercedes-Benz Fashion Week Russia. “Schools in Russia — and many international [ones] too — they’re still using outdated templates to teach. [But] the entire supply chain is changing, and the industry is disrupting, so new skills are desperately needed. We meet young designers every day whose level of knowledge is at 1995 levels, not 2019 levels — even [though] it’s a hundred times easier to start a fashion brand today than it was in 1995. Everything starts at school.”

Increasingly, the trailblazers among fashion entrepreneurs don’t come from fashion schools. Sixteen years ago, while studying applied science, Rinaldo Willy had what most aspiring entrepreneurs are told they are supposed to have — a lightbulb moment. While reading about a process used to isolate carbon from ash to create diamonds in a lab, he pondered whether it was possible to create a “memorial diamond” made from a loved one’s cremation ashes. “Nobody in my own school knew the answer,” he recalls, “so I contacted ETH (Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule) — you know, it’s like the Swiss MIT.”

Entrepreneurship is just the new sexy thing to do.

Since diamonds are 99.9 percent carbon and the human body contains around 18 percent carbon, Willy felt he was on to something. Encouraging him further were statistics showing that cremation rates were rising fast in the US and other high-income countries that once preferred burials. Then came early reports that some of the big diamond players were beginning to worry about the rapid progress made by lab-grown diamond pioneers. And despite initial misgivings, the researchers at ETH eventually provided Willy with enough evidence to conclude that, theoretically, his concept could work.

Having conducted a small amount of market research and drafted a loose business plan, Willy was ready to take a leap of faith. A year later, at the tender age of 23, he launched Algordanza with seed capital worth around $400,000, which he duly spent on equipment and prototyping.

The trope of the genius-entrepreneur is now everywhere. Some are subtle pied pipers while others attract a personality cult; Jack Ma and the now-beleaguered Elon Musk come to mind. But how did we end up with this oddly romantic notion of the modern entrepreneur as some sort of cerebral hustler? And if you believe the clichés, why is it that another quality any good founder seems to need is charisma?

With Elon Musk starring in an episode of “The Simpsons,” and the words “Bill Gates” reborn as a rap lyric used by everyone from Snoop Dogg to Ice Cube and Lil’ Kim to Young Thug, entrepreneurship has gained a certain cachet among the wider public. Somehow, entrepreneurs have upped their cool quotient far beyond their respective industries.

A caricature of Bill Gates | Source: Shutterstock

“Entrepreneurship is just the new sexy thing to do,” offers Peace Hyde, a broadcaster based in Lagos, Nigeria. “That’s [partly] why I launched my own TV show about them,” she adds, referring to the entrepreneurs she interviews for Forbes Africa. With Tinder recently claiming that “entrepreneur” was the second most right-swiped job for men and third for women, there seems to be more than just a grain of truth in this. Indeed, almost 70 percent of the adult population across 52 major countries believes that entrepreneurs are well regarded and enjoy high status within their societies, according to the latest Global Entrepreneurship Monitor Report.

Popular culture hasn’t always helped advance our understanding of entrepreneurship though, and reality TV shows like “Shark Tank” and “Dragon’s Den” have arguably perpetuated more parodies of entrepreneurship than the real thing. Sir Alan Sugar, himself a living stereotype of the gruff rags-to-riches tycoon type, who hosts “The Apprentice” in the UK, believes that “entrepreneurial spirit does lie buried in the subconscious of many people [but] you’ve either got it or you don’t.” For Sugar, “you can’t make someone into an entrepreneur, just like you can’t make someone a pop singer or an artist.”

If Sugar’s views sound too much like the “great man” theory of leadership, they probably are. Instinct, ambition, a nose for opportunity, focus, grit and an appetite for calculated risk all play their part in the making of successful entrepreneurs. But it is unlikely that any single gene sequence or psychographic profile makes us significantly predisposed to life as an entrepreneur. And yet, the enduring notion that entrepreneurs are born, not made, adds to the pressure that many founders feel.

“Fashion entrepreneurs [today] are expected to be the leading force, advancing and disrupting the industry,” says Jazia Al Dhanhani, chief executive of Dubai Design and Fashion Council, who recently partnered with business incubator In5. “Investing time and effort on innovation, connecting to the needs and aspirations of consumers, and embracing technology are just the basic ingredients.” Everyone seems to be reading from the same script nowadays, or at least rattling off the right buzzwords.

But are industry leaders framing entrepreneurship in the right way?

The vast majority of entrepreneurs are what’s known in the field as replicative entrepreneurs. They cut-and-paste familiar business models to lateral markets. They don’t invent something mind-blowing from scratch and they won’t be remembered in 100 years’ time. Some of them, however, will become incredibly successful.

Entrepreneurship is a mindset, at the end of the day.

What is interesting about the current preoccupation with "disruption" is that it is not nearly as new or modern in the discourse of entrepreneurship as one might believe. Around a hundred years ago, the Austrian economist Joseph Schumpeter had already identified innovators and disrupters as the forces behind the "creative destruction" needed for major industrial progress and economic growth. But Schumpeter made an important distinction between "the inventor [who] produces ideas" and the entrepreneur who "gets things done." It was he who coined the term Unternehmergeist, German for "entrepreneurial spirit."

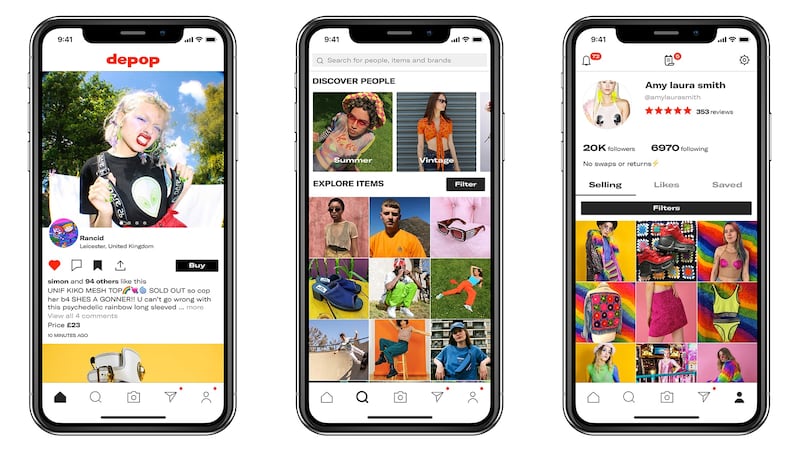

The Depop app storefront | Source: Depop

"Entrepreneurship is a mindset, at the end of the day. Some people are willing to work themselves to the bone in order to become their own boss, or get a product they believe in out in the world. Others are comfortable being comfortable," says Maria Raga, chief executive of Depop, the London-based peer-to-peer social shopping app. "[But I do think that] every thriving entrepreneur has a bit of a '1+1=3' mentality."

“I believe that entrepreneurship can be measured by how you manage to rise from your worst days,” says Forbes’ Hyde. After chronicling Africa’s millionaire and billionaire entrepreneurs for the magazine a few years ago, she began an interview series called “My Worst Day,” where she coaxes subjects to open up on camera about their worst day in business. Episodes called “I Hit Rock Bottom,” “A Mistake that Cost a Million a Month” and “I Could Hear My Children Crying,” always begin with a few ominous piano chords.

Hyde’s subjects are people like Folorunsho Alakija, a Nigerian businesswoman worth more than $1.1 billion, who started her empire in T-shirts before expanding into oil and gas. Africa’s richest self-made woman described the period she spent in an epic court battle with the Nigerian government as feeling “like the plague.” Other formidable entrepreneurs pepper their success stories with experiences of depression, loneliness, broken marriages or the time they spent avoiding calls from their creditors. “People have become a lot more honest about the entrepreneur journey now,” Hyde says.

It was my vision, you know? Either I was going to fall down trying or I had to reach it.

Modern entrepreneurs know that it is in their own interest to talk about their struggles — especially when the bad times are behind them. Silicon Valley’s much-hyped mantra, that failure should be embraced as a natural part of risk-taking and a route to learning, has gained traction among aspiring entrepreneurs around the world.

And yet, a healthy, though not debilitating, fear of failure is how many successful entrepreneurs stay on top. Rinaldo Willy doesn’t seem to be any different in this regard. “It was my vision, you know? Either I was going to fall down trying or I had to reach it,” he says. Although he had to deal with opposition from government agencies, cultural taboos, religious bodies and a naturally sceptical public across very different legal and regulatory jurisdictions, the real challenge was building a brand that could provide such an emotionally-charged service.

Fortunately, he was probably in the most advantageous place on earth to pursue his memorial diamond venture. The entrepreneurial environment is a critical part of the equation but one that is often overlooked.

In a country known for precision, secrecy, trusted brands and the controversial legacy of Dignitas (a non-profit offering assisted suicide to the severely ill), building a business around gems for the bereaved — even when they are made from the ashes of loved ones — was unusual, but it didn’t sound as farfetched in Switzerland as it might have elsewhere. “We as Swiss, we are humble, we don’t brag; this is private,” he says, like a mantra.

In the years since he launched Algordanza, “standard” lab-grown diamonds using similar HPHT technology (high pressure, high temperature crystal synthesis) have begun to disrupt the wider jewellery industry — making his business more popular and credible in the process. A couple of rivals doing something similar have since surfaced. “One Russian, one American, but they need to refine [and] we still have the technical advantage,” Willy claims. Otherwise, he is without any serious competitors.

We are blocked in our expansion, we are a victim of our own success.

In the same way that Willy can’t compete with conventional jewellers, they can’t compete with him. For a product like Algordanza that feels genuinely priceless, neither the design of Chopard, nor the heritage of Tiffany, nor the quality of De Beers even come into the purchasing decision for most of his clients. Besides, brands like these have the joyous milestones covered and would probably do everything in their power to avoid venturing into the “death do us part” segment of the market.

There are no entry-level items in Algordanza’s brand universe either. A single memorial diamond starts at $3,500 and larger gems can fetch five times that price, but a few years ago production capacity maxed out at just shy of 100 pieces per month. Willy’s enterprise has grown to the point that he is making “millions, but not [yet] billions.” The thing that appears to be stopping him moving past the current growth impasse is keeping the manufacturing process Swiss-made under his direct supervision on the existing premises.

“There are big markets that would give us a very fast [growth] impact like India and [mainland] China, but we’re afraid to even offer our services there because we know that once we enter, we wouldn’t be able to keep up with so much demand,” he explains. As it stands, Algordanza can barely keep up with orders from its current footprint in 30 international markets. “We are blocked in our expansion, we are a victim of our own success,” concedes Willy.

“They say that entrepreneurs are the people changing the world,” he muses. But it’s more about responding to the world than ripping up the proverbial rulebook. “If we don’t continue to adapt to the market, adapt to changing technology and adapt to our changing customers, then we very quickly become nothing.”

Additional research by Sophie Soar.

Listen to this article:

Related Articles:

[ How De Beers Learned to Love Lab-Grown DiamondsOpens in new window ]

[ Redefining Modern Entrepreneurship at the BoF China SummitOpens in new window ]

The app, owned by TikTok parent company ByteDance, has been promising to help emerging US labels get started selling in China at the same time that TikTok stares down a ban by the US for its ties to China.

Zero10 offers digital solutions through AR mirrors, leveraged in-store and in window displays, to brands like Tommy Hilfiger and Coach. Co-founder and CEO George Yashin discusses the latest advancements in AR and how fashion companies can leverage the technology to boost consumer experiences via retail touchpoints and brand experiences.

Four years ago, when the Trump administration threatened to ban TikTok in the US, its Chinese parent company ByteDance Ltd. worked out a preliminary deal to sell the short video app’s business. Not this time.

Brands are using them for design tasks, in their marketing, on their e-commerce sites and in augmented-reality experiences such as virtual try-on, with more applications still emerging.