The Business of Fashion

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

NEW YORK, United States — An opulent purple satin sheath by Jean Paul Gaultier reflects the Asian woman's "mysterious powers of sexual mastery," read the caption accompanying an image of the dress on Vogue.com. An Yves Saint Laurent gown represents "the cinematic stereotype of the dragon lady in a tight sheath," read another caption. Indeed, creations like these represent the way an overwhelming number of designers view Chinese fashion: centred on a fantasy of China, created largely for Western consumption.

Many of the 140 dresses on display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art's Costume Institute exhibit, China: Through the Looking Glass, which kicked off with the annual Costume Institute Benefit (or Met Gala) on Monday and opened to the public yesterday, are recent creations — some created within the past decade. And yet, they represent a bygone era in the global fashion industry. Now that targeting Chinese shoppers is a key focus for most, if not all, of the brands on display at the exhibit, designers must create clothes for China, not just about China.

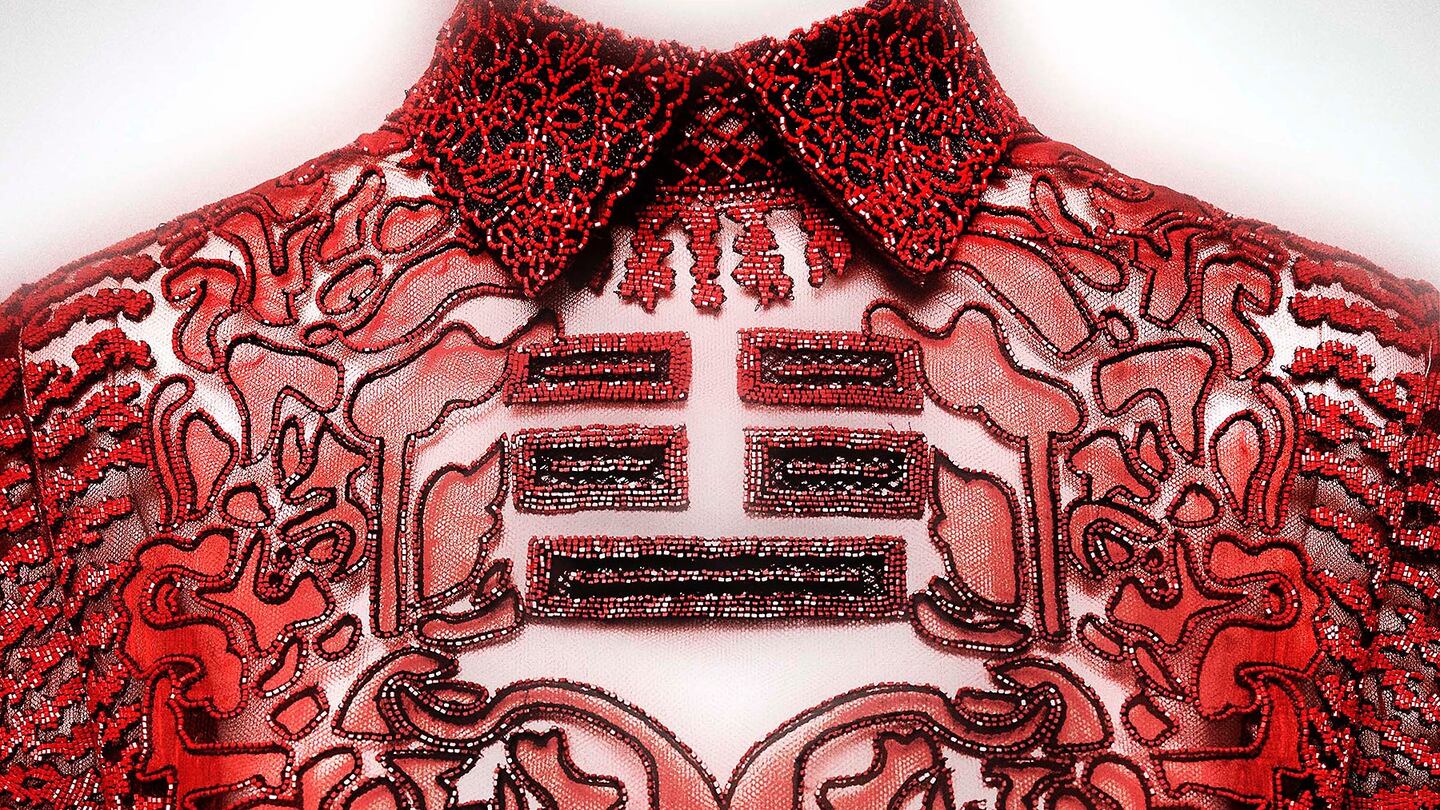

The exhibition may have "China" in the name, but as Andrew Bolton, curator of The Costume Institute, recently said to Jing Daily: "a lot of designers are not inspired by the real China." In an interview with BoF, he went further, explaining that, the show was about "a fantasy of China, one that is shared between the East and the West." Much of this fantasy was driven by classic films set in 1920s, '30s and '40s China, as the Met points out in its description of the event. But these films often had highly problematic themes. For example, The World of Suzie Wong (1960), a British-American film that inspired a Chanel qipao on display in the exhibit, is frequently criticised for racism and sexism, while many of the films starring renowned Chinese-American actress Anna May Wong typecast the actress as a 'painted doll' or a 'scheming dragon lady'—both cinematic stereotypes of Asian women.

However, many of the dresses on display are not guilty of such stereotypes. Rather, they take inspiration from Chinese artwork or films by Chinese directors, but the Met makes clear that they do represent the sartorial equivalent of "orientalism,” a term that historically refers to the study of the “Orient,” a geographical region including Asia and the Middle East.

ADVERTISEMENT

When professor Edward Said published Orientalism in 1978, he pointed out the problematic side of works of art or literature deemed "orientalist," noting that they often relied on patronising racial stereotypes of exotic or mystical Eastern cultures, which tended to portray them as static and backward. According to Said, orientalism was out of touch with on-the-ground realities in Asian and Middle Eastern countries.

Speaking to BoF, Bolton agreed that many of the dresses on display at the exhibition fit the rubric of orientalism, but argued that this isn’t a negative when it comes to fashion because it represents an exchange of ideas and China’s role as an honoured source of influence. “I wanted to show the reciprocal relationship between the East and West that has always existed,” he said.

For the fashion designers with pieces on display, however, it will ultimately be wealthy Chinese consumers that cast the deciding vote on this issue — with their wallets. Chinese-inspired designs simply won’t resonate with Chinese consumers if they show a lack of understanding of their culture. China can no longer exist as mere fantasy for fashion brands if they want to stay in business. Indeed, the perception that a garment is culturally tone-deaf could seriously harm sales.

Over the past decade, Chinese luxury spending has grown tenfold and, in 2014, represented 30 percent of the global luxury market, according to a 2014 report by Bain & Co and Italian luxury goods foundation Fondazione Altagamma. This reflects a rapid and groundbreaking change, since 10 years earlier (when many of the dresses at the exhibit were created) China accounted for only three percent. Chinese consumers make up 38 percent of Prada's customer base, 37 percent of Gucci's, and 35 percent of Bottega Veneta's and Burberry's, according to estimates from Exane BNP Paribas.

Designers have become acutely aware of this shift, as the Met's exhibition makes clear. One Valentino dress on display is part of an 85-piece capsule collection, created exclusively for the China market and presented in a special Shanghai runway show in 2013. Rather than featuring outfits that look like they belong on the set of Suzie Wong, the collection nodded to Chinese aesthetics through its red colour palette, but included many wearable pieces, designed for the urban Chinese consumer.

The organisers of the Met exhibit have also considered the importance of their Chinese audience. Hong Kong film director Wong Kar-Wai is the exhibition's artistic director, while Chinese actress Gong Li served as one of the co-chairs of the Met Gala. American Vogue's editor-in-chief Anna Wintour travelled to Beijing in January to promote the exhibition. The Metropolitan Museum of Art also secured the loan of a robe worn by Pu Yi, China's last emperor, to display at the exhibition.

The exhibition features film clips by Wong, as well as Chinese directors Zhang Yimou, Chen Kaige and Ang Lee, and a few pieces by Chinese designers including Guo Pei, Laurence Xu and Vivienne Tam. The Costume Institute has also teamed up with the museum's Department of Asian Art to display the dresses alongside the original Chinese garments, paintings, porcelains and art that inspired them.

However, the mass public's perception of the exhibition will be shaped largely by images from the Met Gala, which had a "Chinese white tie" dress code. Before the event, many speculated that confused celebrities would show up in culturally insensitive attire. On the night, while most of the red carpet fashion was China-themed, it was not created by Chinese designers — rather, New York stalwarts like Roberto Cavalli and Ralph Lauren, or international brands including Gucci, Maison Margiela and Alexander McQueen.

ADVERTISEMENT

A few blocks down from The Costume Institute, at Barney's, a special edition capsule collection by Qingdao-born, London-based designer Huishan Zhang is on sale in celebration of the exhibition. Zhang, who founded his label just months after his graduation from Central Saint Martins, is part of a crop of emerging young Chinese designers such as Masha Ma, Yang Li and Yiqing Yin, whose labels are shown at key fashion weeks worldwide and have won the support of global stockists; in Zhang's case, Harvey Nichols, Joyce, TSUM and Browns Fashion.

The next time the Met’s annual fashion exhibition is China-themed, Chinese names, rather than Western ones, will likely be the ones taking centre stage.

Liz Flora is the editor-in-chief of Jing Daily.

The views expressed in Op-Ed pieces are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Business of Fashion.

Join the discussion on BoF Voices, a new platform where the global fashion community can come together to express and exchange ideas and opinions on the most important topics facing fashion today.

Editor’s Note:

This article was revised on 14 May, 2015. An earlier version of this article misstated that Anna Wintour secured the loan of a robe worn by Pu Yi, China’s last emperor, to display at the exhibition. She did not. The Metropolitan Museum of Art secured the loan.

With consumers tightening their belts in China, the battle between global fast fashion brands and local high street giants has intensified.

Investors are bracing for a steep slowdown in luxury sales when luxury companies report their first quarter results, reflecting lacklustre Chinese demand.

The French beauty giant’s two latest deals are part of a wider M&A push by global players to capture a larger slice of the China market, targeting buzzy high-end brands that offer products with distinctive Chinese elements.

Post-Covid spend by US tourists in Europe has surged past 2019 levels. Chinese travellers, by contrast, have largely favoured domestic and regional destinations like Hong Kong, Singapore and Japan.