The Business of Fashion

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

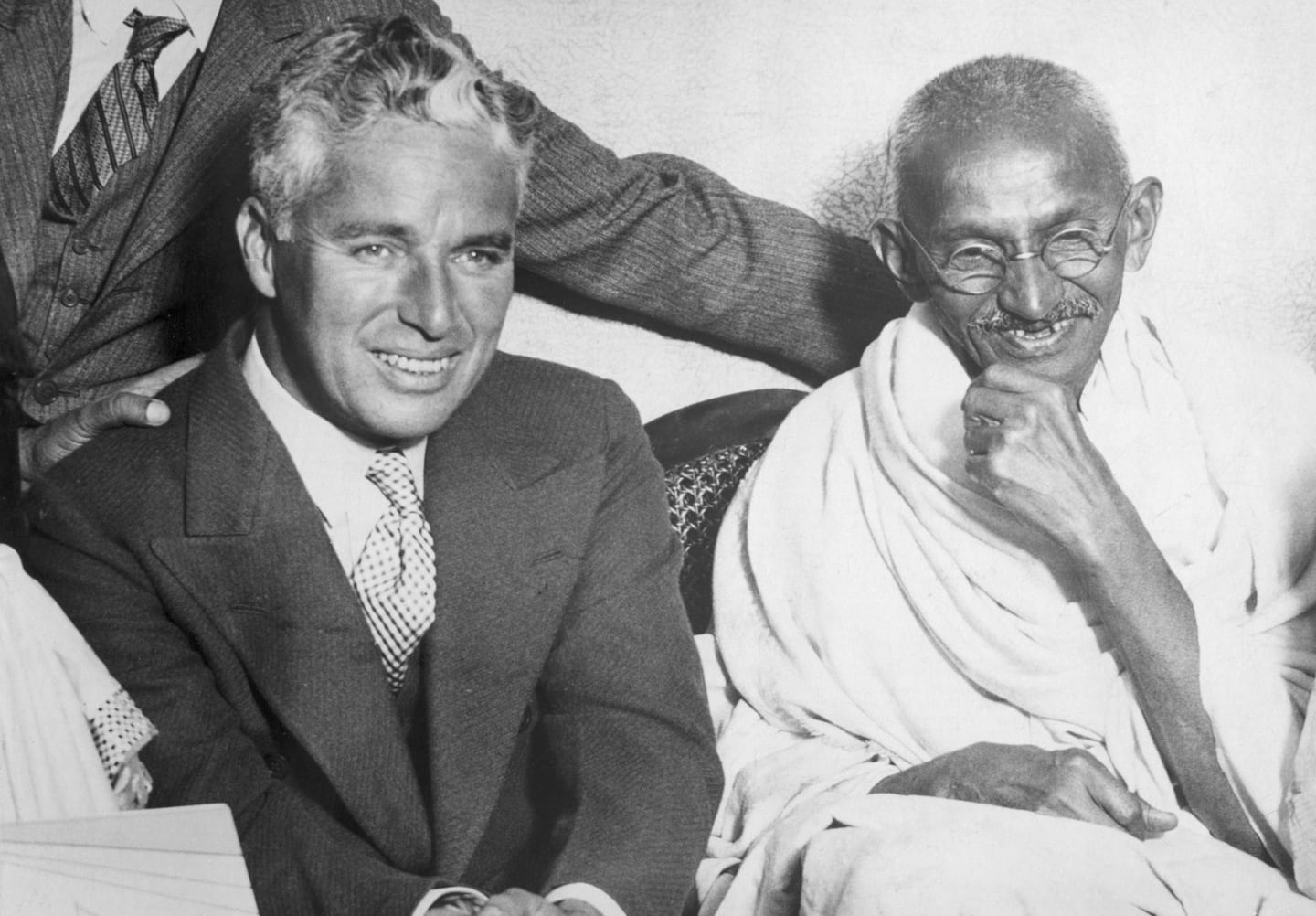

It was a momentous meeting between Charlie Chaplin, the Little Tramp, and Mahatma Gandhi, the Little Leader. It happened, according to Chaplin’s My Autobiography on a balmy day in September 1931 in a “humble little house” in a slum district off London’s East India Dock Road. Both men, surprisingly, had a lot in common, including their love for cockney slang and a genuine empathy for underdogs and the poor working classes.

Gandhi was in London to participate in one of the three Round Table Conferences organised by the British government and Indian political figures to discuss constitutional reforms in colonial India. He arrived seeking independence from the British, dressed in his iconic loincloth made of the hand-spun fabric khadi, a sartorial symbol of his identification with India's poorest of the poor, to which Winston Churchill scoffed: "the half-naked fakir."

In the brief encounter between Gandhi and Chaplin, Chaplin explained that whilst he was rooting for India’s independence, he couldn’t understand Gandhi’s “abhorrence of machinery.”

See, Gandhi saw a manifestation of colonial hegemony in the “machinery” that had made India dependent on foreign factories to produce its clothes, which went against his deep belief in Swadeshi or economic self-reliance. He had therefore initiated the khadi movement, which sought a nationwide ban on clothes made in the mills of Britain, galvanising Indians to instead pick up the humble spinning wheel and weave their own khadi.

ADVERTISEMENT

Today, the tables are turned. India is the world's second largest textiles manufacturer. The country benefited from a major boost as global demand for cloth soared during the Second World War. But symbolically, the legacy of Gandhi’s khadi movement played a pivotal role in loosening the psychological shackles that haunted India’s post-colonial textile industry.

The khadi movement did not mean a rejection of modern machinery and technology, per se. It was a symbolic gesture designed to curb the power of a garment industry that was inextricably bound up with oppression, and still is today, especially in neighbouring Bangladesh, where garment workers have, in essence become as commoditised as the raw materials that the British extracted from colonial India.

This level of vulnerability lays bare a major power imbalance: it is the foreign brands who ultimately make the rules.

Today, amid the pandemic, these garment workers face ruin as big global brands have cancelled clothing contracts worth an estimated $3.7 billion, causing the furloughing or firing of more than half the 4.1 million garment workers in the country, mostly women, whose average $110 per month pay is crucial to their survival. Indeed, when the garment industry accounts for 80 percent of Bangladesh's exports, it took just a handful of major fashion brands in Europe and the US to bring an entire country to a grinding halt and sending thousands of workers into the streets to protest, risking infection because with unpaid wages comes a deadlier malaise: starvation.

“This is a human rights violation,” says Mostafiz Uddin, managing director of Denim Expert Ltd, who employs 2,000 people and had an annual turnover of $18 million with exports going to the US and Europe. “Because of the brands’ non-payment to the factories in the form of cancelled orders, [delays] and coercion for discounts, the factory workers are now struggling to lead their lives. This blasé breach of contract, wherein the workers are not being paid for their labour by the buyers, is a sheer violation of human rights. We are being treated inhumanely.”

This level of vulnerability lays bare a major power imbalance: it is the foreign brands who ultimately make the rules. And when these companies look to developing nations simply as sources of cheap labour, workers valued only for the number of hours they clock in whilst creating more and more cheap clothes, oppression is never far away. If this is not modern-day colonisation, what is?

This brings us right to the heart of Gandhi’s quest for Swadeshi. He knew back then that colonisation had deepened appalling inequalities. He unleashed the spinning wheel as a powerful symbol of self-sufficiency yes, but also to slow down the methods of making and consuming. For Gandhi, Swadeshi was a programme for long-term survival. He envisioned a decentralised, home-grown, hand-crafted mode of production: “not mass production, but production by the masses,” he said, where each village would thrive in their own ecosystem of skills, services, production and distribution.

So back to Chaplin. The encounter with Gandhi left an indelible mark on the actor. A few years later, he released his seminal film Modern Times, a critique of overworked employees and corporations that value these workers only for the time that they are producing for them and, indeed, the predominance of machines over people.

Has anything really changed? Yes and no.

ADVERTISEMENT

Gandhi was a proponent of ahimsa, or non-violence in thoughts, words and deeds, and aparigraha, or non-greediness. Could these values show the path to a more conscious fashion world? Let us remind ourselves that one man and his conviction electrified millions in India. So much so that, in 1931, the Indian National Congress adopted a flag featuring Gandhi’s humble spinning wheel that, when India finally gained independence from Britain, informed the design of its national flag.

Editor’s Note: This article was revised on 21 May 2020. An earlier version of this article misstated that Gandhi’s spinning wheel adorned India’s national flag after its independence from Britain. This is incorrect. The Indian National Congress adopted a flag featuring Gandhi’s spinning wheel in 1931, but the spinning wheel of the Congress flag was replaced by the Chakra wheel from the Lion Capital of Ashoka in 1947 when the country gained independence.

Bandana Tewari is a lifestyle editor and sustainability activist and was formerly editor-at-large at Vogue India.

The views expressed in Op-Ed pieces are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Business of Fashion.

How to submit an Op-Ed: The Business of Fashion accepts opinion articles on a wide range of topics. The suggested length is 800 words, but submissions of any length will be considered. Submissions may be sent to contributors@businessoffashion.com. Please include ‘Op-Ed’ in the subject line. Given the volume of submissions we receive, we regret that we are unable to respond in the event that an article is not selected for publication.

Related Articles:

[ A Humble Fabric Helped India Fight British Rule. Now It's Big Business.Opens in new window ]

[ Fashion Workers Left Destitute in IndiaOpens in new window ]

This week’s round-up of global markets fashion business news also features Latin American mall giants, Nigerian craft entrepreneurs and the mixed picture of China’s luxury market.

Resourceful leaders are turning to creative contingency plans in the face of a national energy crisis, crumbling infrastructure, economic stagnation and social unrest.

This week’s round-up of global markets fashion business news also features the China Duty Free Group, Uniqlo’s Japanese owner and a pan-African e-commerce platform in Côte d’Ivoire.

Affluent members of the Indian diaspora are underserved by fashion retailers, but dedicated e-commerce sites are not a silver bullet for Indian designers aiming to reach them.