The Business of Fashion

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

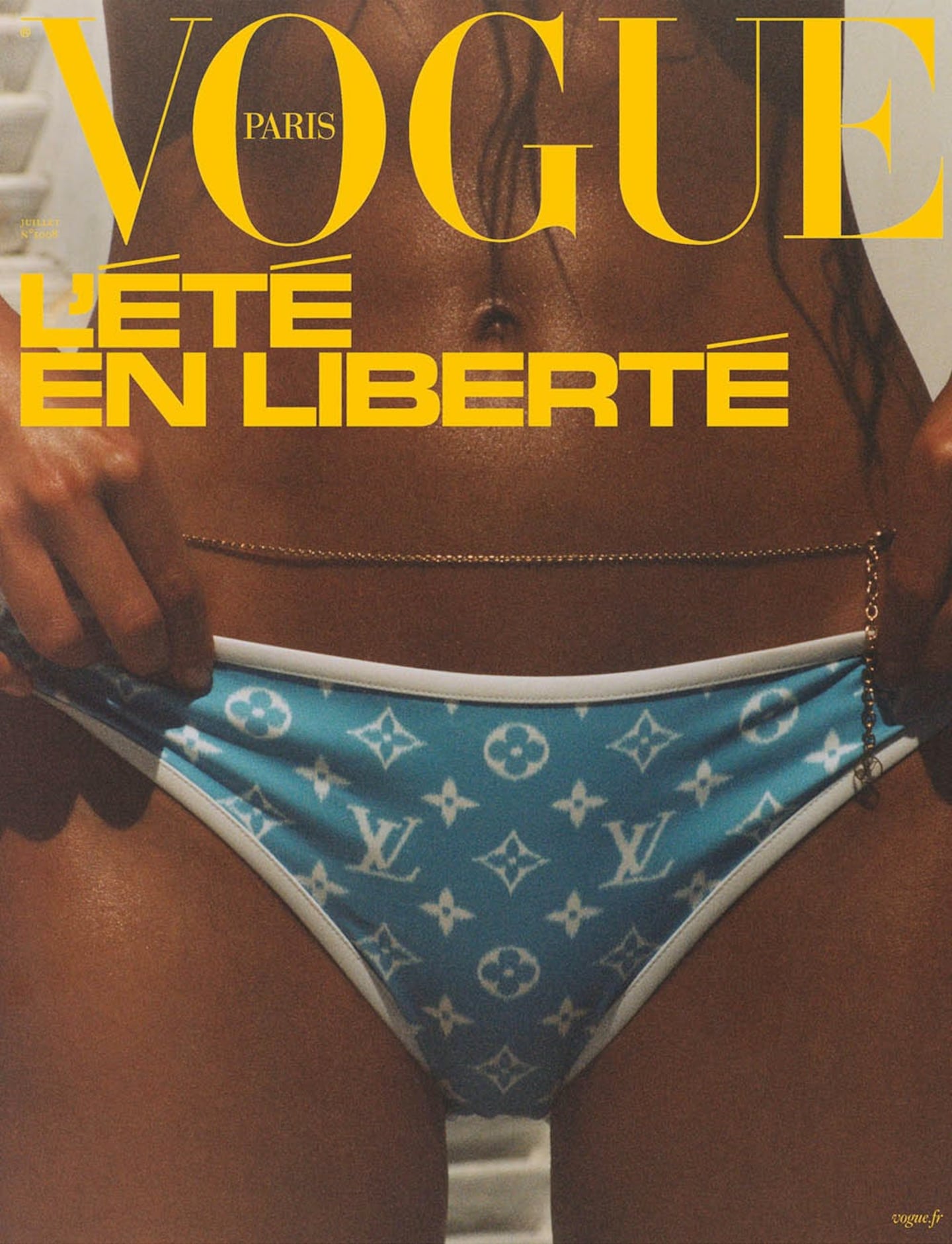

The July 2020 cover of French Vogue featured the torso and crotch of a brown-skinned woman wearing a sky-blue bikini bottom emblazoned with Louis Vuitton’s signature monogram and tipped in white, making for an arresting contrast between fabric and body colour. But not everyone was happy with the image.

When the cover was first revealed on Vogue Paris' Instagram account, commenters accused the magazine (and in turn, Danish-born model Natasja Madsen, who is naturally fair skinned but appears to tan easily) of "Blackfishing," or the act of a white person making themselves appear to look Black by changing their appearance.

"It's just ridiculous to use such a large amount of fake tan and/or editing when there are plenty of black models and models of colour out there," commented photographer and art director Adama Anotho on the Vogue post.

Soon enough, however, Anotho's comment was deleted. Her second one as well. "The consideration of racism and blackfishing at Vogue Paris is close to nothing," she later explained. "They don't need to tackle it. When you take a closer look, once the occasional outrage has passed, nothing threatens their comfort, functioning, or influence."

ADVERTISEMENT

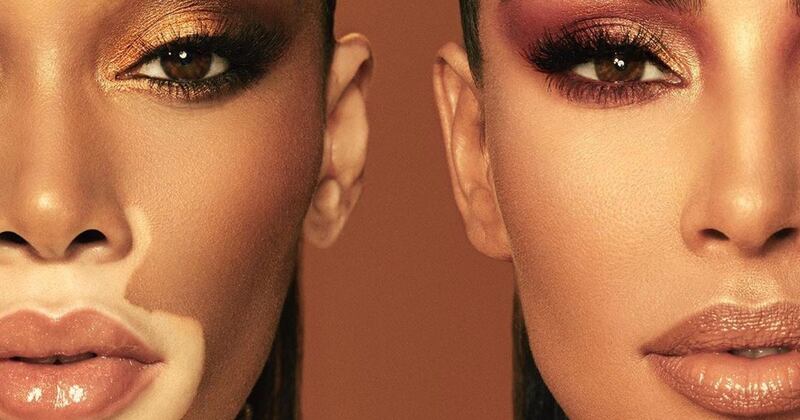

Kim Kardashian was accused of Blackfishing after an ad for KKW Beauty featuring Kardashian and Winnie Harlow circulated online | Source: KKW Beauty

French media consultant Elise Goldfarb also claims her comments were deleted. She then took her frustration to the personal account of Emmanuelle Alt, Vogue Paris' editor in chief. She said she was blocked. "The problem is not that she is blocking the influencer that I am," Goldfarb wrote in an email. "The problem is she deleted a comment that wasn't a physical nor moral attack." Alt declined a request for comment.

As it turns out, the cover shows Madsen’s actual tan, shot by her boyfriend on film without any editing while they were under lockdown, the model said via Instagram direct message.

But in the wake of the police killing of George Floyd, when racial sensitivity is running high and a new civil rights movement is growing, the Blackfishing debate raged on.

Blackfishing — a spin on "catfishing" — has played a role in image-making for decades, even if the term was only popularised in 2018 by journalist Wanna Thompson, who started a viral Twitter thread referencing white influencers believed to be, consciously or unconsciously, looking like a person of colour.

In 2010, long before Thompson's tweet, Roberto Cavalli darkened the skin of two white models to make them appear brown for an ad campaign. In 2013, Numéro magazine shot a 16-year-old white model in blackface for an "African Queen" shoot.

"When you look at campaigns in fashion and beauty, you might have one token [non-white] person," said Minàl Malik, a marketing lecturer at the London College of Fashion. "But most of the time, when they are using diverse models, they are essentially white with a bit of a tan or slightly crimped hair to make it seem like they're on the fringe of a different race."

Taking inspiration from Black culture isn’t the problem in and of itself; appropriating a skin tone, or a hair or body type to make money without including Black people in the process is the issue, say critics, because it deprives them of opportunities. In the end, white women who Blackfish cosplay exotism while enjoying their white privilege, they argue.

ADVERTISEMENT

In recent years, magazines and brands have been more regularly scrutinised for altering the colour of models' skin. When Gigi Hadid covered Vogue Italia in 2018 with an unusually darkened complexion, a social media uproar compelled her to address the issue.

Many models and image-makers accused of Blackfishing have supported the Black Lives Matter movement on social media. But few have addressed the damage critics say Blackfishing can do to Black people: not only depriving them of employment opportunities, but sanctioning cultural appropriation.

They are using white or mixed race people to represent Blackness in a way that is still very white.

Braids or dreadlocks that have gotten Black pupils sent home from school can become high style when they are appropriated by the Kardashians or Marc Jacobs.

For Adesuwa Ajayi, senior talent and partnerships lead at AGM Talent, a UK-based influencer agency, who runs the Instagram account Influencer Pay Gap, when appropriators position themselves as originators, earning exposure and money using historically Black culture, they benefit themselves while erasing Black talent.

Italian-American singer Ariana Grande has been accused of Blackfishing on several occasions. She had a lighter complexion as a teenage actress but later morphed into a worldwide pop star with brown-looking skin.

Ariana Grande at the Grammy Awards in January 2020 in Los Angeles | Source: Getty Images

Kim Kardashian, the daughter of a Dutch, English, Irish, German and Scottish mother and an Armenian father, has also faced backlash for Blackfishing. An ad for KKW Beauty showed her alongside Black model Winnie Harlow, who looks lighter than Kim, sparking uproar.

While celebrities and brands deny they intentionally participate in Blackfishing, some say it’s a conscious marketing strategy. “For many brands, the decision to elevate those who have built entire platforms through impersonating Black women is intentional,” Ajayi said.

ADVERTISEMENT

To be sure, Black culture is ‘cool’ and highly marketable. And, everyone from Elvis Presley to Justin Timberlake, has profited from this. But it’s not that simple.

“They are using white or mixed race people to represent Blackness in a way that is still very white and that is not Black enough to make white people uncomfortable,” explained Dr. Margaret Hunter, a sociology professor at Mills College in Oakland, California. “But [it’s also] a little bit Black so as to make Black people feel somewhat included.”

Washington Post journalist Karen Attiah sees a similarity between Kim Kardashian's desire to appear darker and "America's obsession with Blackness, and Black culture — without Black people."

“There has always been this utilisation of Blackness because it has been seen as this fantasy devoid of humanity,” said music journalist Taylor Crumpton. “Everybody wants to take on the benefits without having to experience all the inequalities that come from Blackness. The easiest way to do this fantasy is in entertainment spaces like music.”

Hunter believes, choosing to darken your skin goes hand in hand with butt surgery and lip fillers. “Women of colour are so overtly sexualised that [white women] can increase their sexiness by ticking certain aspects of these stereotypes,” she said. ”However, their whiteness is never in question. They don’t want to give that away, they wanna be white with the racial meaning of these various body parts.”

In the influencer community, few accused of Blackfishing have been compelled to examine their behaviour. “I do not see myself as anything else than white… I get a deep tan naturally from the sun,” Swedish influencer Emma Hallberg told Buzzfeed in 2018, after she was accused of presenting herself as a racially ambiguous woman to further her career.

"There is a tendency to elevate ethnically ambiguous influencers and use them in spaces that should otherwise be reserved for Black creators," said Ajayi. "This is often a poor attempt at appearing more diverse, with hopes no-one will notice."

One misstep and the social justice warriors will come for you.

The incident has done little to slow Hallberg’s success. Today, she has more than 449,000 Instagram followers and is growing her audience at a steady rate, according to Hype Auditor. In July 2020, she published 14 sponsored posts promoting clothes from the likes of Fashion Nova and Pretty Little Thing. (Both companies declined to comment.)

But marketing may not be the only force at play.

“If a brand has been called out countless times but insists on ignoring a large pool of individuals, many of whom have at some point purchased their products, that issue isn't solely an issue exclusive to whatever is on their marketing agenda at the time,” said Ajayi. “It can also be a reflection of the general makeup of that company; inherent within that culture you'll find that there is a complete disregard for those who do not look like them.”

Change takes time, money and careful planning. “One misstep and the social justice warriors will come for you,” warned Gabriella Santaniello, founder of retail research firm A Line Partners. “Some of these brands like Fashion Nova, Pretty Little Thing and Boohoo, can’t automatically go from being tone deaf to 'We're fully representing POC.’ It is a lot of work. They can say all they want; at the end of the day it has to be followed up by action.”

But until consumers care in larger numbers and begin voting with their dollars, there may be no end to Blackfishing. "If the consumer suddenly moved on from copying the Kardashians there would be no demand for them," said fashion journalist Louis Pisano, "and the cycle of imitating their cultural appropriation would be broken."

The views expressed in Op-Ed pieces are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Business of Fashion.

How to submit an Op-Ed: The Business of Fashion accepts opinion articles on a wide range of topics. The suggested length is 700-1000 words, but submissions of any length within reason will be considered. All submissions must be original and exclusive to BoF. Submissions may be sent to opinion@businessoffashion.com. Please include 'Op-Ed' in the subject line and be sure to substantiate all assertions. Given the volume of submissions we receive, we regret that we are unable to respond in the event that an article is not selected for publication.

Related Articles:

[ Fixing the Whitewashed Influencer EconomyOpens in new window ]

[ Op-Ed | Fashion Is Part of the Race ProblemOpens in new window ]

[ Voices From the Black Fashion Community on Moving ForwardOpens in new window ]

From analysis of the global fashion and beauty industries to career and personal advice, BoF’s founder and CEO, Imran Amed, will be answering your questions on Sunday, February 18, 2024 during London Fashion Week.

The State of Fashion 2024 breaks down the 10 themes that will define the industry in the year ahead.

Imran Amed reviews the most important fashion stories of the year and shares his predictions on what this means for the industry in 2024.

After three days of inspiring talks, guests closed out BoF’s gathering for big thinkers with a black tie gala followed by an intimate performance from Rita Ora — guest starring Billy Porter.