The Business of Fashion

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

NEW DELHI, India — The Saket Select Citywalk mall is where New Delhi's fashion-literate middle class comes to shop. There are Zara dresses, Gap sweaters, MAC cosmetics, all in an air-conditioned sanctuary. The latest arrival to the mall is a two-storey H&M store, India's first.

“A t-shirt at H&M costs 799 rupees (about $12), or even less. It will affect Zara. Zara will go down,” says Sukhmani Sodhi, 20, an undergraduate on her way to a class at Shaheed Bhagat Singh College, Delhi University. Can she afford to shop at the Swedish brand, which has stores in 60 markets, and posted net income of $630 million in the quarter ending this August? Of course she can, she shoots back, a little offended.

The Zara comparison has got everyone talking. After five years in the country and with 16 stores now open, this July, Zara became the first apparel brand to cross the $100 million sales mark in India. When the H&M store opened at the end of last month, Indian newspaper Business Standard contrasted the queues at H&M with photos of relatively quiet Zara and Gap stores. The question is: why has it taken H&M so long?

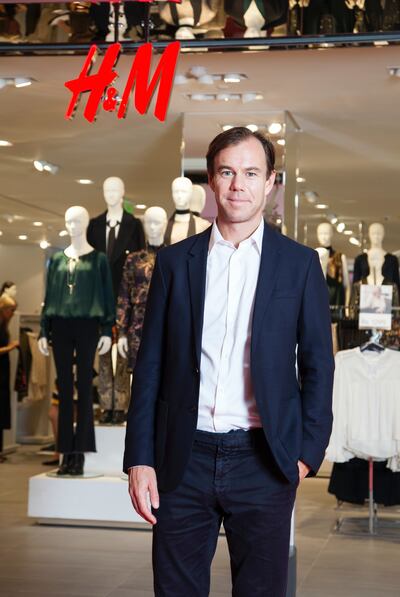

"We have known for many years, India is a significant market," says Karl-Johan Persson, chief executive officer of H&M, sitting in a corner of the new store, which is buzzing with activity as staff prepare to receive its first customers. "But then we have to get approvals to go into a country. It took a little bit of time. It is a process," he adds, as an army of attractive, tattooed visual merchandisers run around putting the final touches to mannequins and sales assistants funnel in and out of the stock room. "For the first store in a new market there is a lot of work. It requires lots of resources."

ADVERTISEMENT

Indeed, the costly four-page advertisements in all of New Delhi’s major daily newspapers attest to that. What’s more, until 2012, single-brand retail in India was limited to 51 percent foreign ownership. In January 2012, India’s government approved reforms on single-brand retail, which opened the doors for global companies to have full ownership of their operations in India. “That includes merchandising, branding, promotions, pricing, etcetera,” says Arvind Singhal, chairman of consultancy firm Technopak Advisors. “A joint venture requires both partners to share a very similar mindset and that is not always easy to achieve.”

Zara’s entry into India — through Inditex Trent, a joint venture between parent company Inditex and Trent, the retail arm of Indian operating company Tata Group — predated the advent of single-brand retail. Inditex Trent posted 24 percent annual growth in sales for the year ending March 2015, though sales growth almost halved from 43 percent the previous year. However, H&M’s expansion strategy does not favour the franchise model (with the exception of a few markets where, for regulatory reasons, it takes on partners). “For us, it has always been the preferred mode, to run the business on our own,” says Persson, dressed in a black blazer and white shirt from H&M’s upmarket sister brand Cos.

But it is not just Zara that the Swedish clothier has to worry about. India’s young shoppers are well-versed in e-commerce, tapping away on their mobiles to create a $16 billion market by the end of 2015, according to ASSOCHAM-Deloitte, and giving rise to a clutch of e-tailers such as Flipkart and Snapdeal. Topshop partnered with e-tailer Jabong to launch e-commerce in India last month, but currently has no bricks-and-mortar stores in India.

H&M has not yet launched e-commerce in India, but Persson says he has arrived in the country with digital natives in mind: “I think it’s a boom that is going on in many countries. We haven’t decided, but the aim is to come with an online store also. We have an online store in 21 markets.”

India is a complex market to crack. Shopping destinations can range from the Sarojini Nagar flea market, where a graphic t-shirt costs 150 rupees (about $2), to Indian high-street labels such as Fabindia and Anokhi that stitch everything from dresses to kurtas in block prints or bandhni. “India has always had a somewhat unique retail environment where all kinds of retail establishments co-exist. We do not have the western-style designated high-streets per se, barring a few exceptions,” says Singhal.

Culture continues to play a role in what Indians wear, especially women whose choices can be heavily influenced by conventions and social diktats. Interest in couture has the likes of the LVMH and Kering competing with Indian designers such as Tarun Tahiliani and Sabyasachi Mukherjee, whose work Persson says he admires.

However, H&M does not have a design offering specifically created for the Indian market. Pernilla Wohlfahrt, who heads up design at H&M, believes that Indian shoppers are looking for the same collections that are available in New York, London or Paris: “We follow our customers closely. You are very fashionable. You follow the same celebrities, the same bloggers. Fashion is global today.” Agrees Persson: “Fashion interest in India is huge, diversity is huge as well.”

Some H&M clothes already mix sensibilities of different countries to arrive at a “global, ethnic style”, says Wohlfahrt, pointing to a top in the style of a Japanese kimono. What, in her eyes, are the specific needs of the Indian market? “We don’t know yet. You are very colourful, we can add colour. We are also looking at the climate, we can add more transitional clothes. We will start following you more closely.”

ADVERTISEMENT

Karl-Johan Persson, CEO of H&M | Source: Courtesy

Some investors are still put off entering India due to red tape and corruption. Prime minister Narendra Modi, who has just completed a tour of Silicon Valley, wants India to make it into the top 50 countries for ease of doing business. It is currently ranked 142.

But India is attracting attention from investors, partly due to the recent economic slowdown in China, where H&M is nearing 300 stores. H&M remains confident about India’s powerful neighbour, while many luxury goods companies’ growth in China has plateaued, in part because many of its high-end consumers prefer to shop abroad. The middle class, however, travels less and continues to shop on home turf.

The size of India’s own middle class is not easy to quantify. In 2013, 224 million people, or a quarter of India’s 1.2 billion-strong population were defined as “middle class” according to standards set by the Asian Development Bank. But while this group falls into the top third, by wealth, of Indian society, its purchasing power falls short of the middle class in developed nations — four-fifths of India’s middle class fall into the lowest bracket of purchasing power, meaning they are able to spend $2 to $4 a day.

However, the consumer market is growing: household consumption in India is expected to quadruple from 2005 to 2025, according to McKinsey Global Institute. Renault’s SUV Duster (priced at 8 to 9 lakh rupees, or about $12,000) is a hot-seller, while Apple is increasing its distributors and authorised sellers in India.

Persson first visited India in 1999 and H&M has sourced from the country since 1995. The Indian government’s 2012 reforms to single-brand retail require that retailers source at least 30 percent of their goods from India — a condition that companies including Ikea have struggled to meet. “The sourcing from India is big today but it will continue to grow. We are working with more than 100 suppliers, mostly around Bangalore… we are fulfilling all the criteria,” says Persson, who declined to say if H&M had to increase its sourcing in India before opening its first store in the country, but added, “Some changes have been done.”

On the way out of the shiny new store, I spy a bin where shoppers can drop off second-hand clothes as part of H&M’s sustainability efforts. Most Indians already recycle everything from old clothes to old newspapers — compared to western countries, it is not clear if the initiative will have a significant impact on India’s existing recycling economy.

As to where in India we can expect H&M to open next, Persson remains tight-lipped. However, Mumbai and Bangalore are next up on his travel itinerary. “India has a huge population. I think its economy will grow,” he says. This year, for the first time, the World Bank growth chart forecast named India the fastest-growing major economy worldwide, with an expected growth rate of 7.5 percent this year, surpassing China for the first time since 1990. By 2017, the World Bank predicts that India’s growth will reach 8 percent, while China’s will slow to 6.9 percent. “India is probably one of the most exciting markets in the world,” Persson concludes.

Though e-commerce reshaped retailing in the US and Europe even before the pandemic, a confluence of economic, financial and logistical circumstance kept the South American nation insulated from the trend until later.

This week’s round-up of global markets fashion business news also features Korean shopping app Ably, Kenya’s second-hand clothing trade and the EU’s bid to curb forced labour in Chinese cotton.

From Viviano Sue to Soshi Otsuki, a new generation of Tokyo-based designers are preparing to make their international breakthrough.

This week’s round-up of global markets fashion business news also features Latin American mall giants, Nigerian craft entrepreneurs and the mixed picture of China’s luxury market.