The Business of Fashion

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

LONDON, United Kingdom — At the start of July, ultra fast-fashion group Boohoo's share price was near an all-time high. Then, scandal hit. The company was engulfed in allegations of labour rights abuses linked to a coronavirus outbreak in the English city of Leicester.

The financial fallout has been swift and brutal. Boohoo's share price is down nearly 35 percent since the start of the month. Retailers including Next, Asos and Zalando dropped the brand from their stores. And Aberdeen Standard Investments, one of the company's biggest investors, divested its stake.

The juddering crash comes amid mounting scrutiny of fast fashion by consumers, investors and regulators, who are increasingly critical of the social and environmental impact of low-cost, high-volume producers. In the last few months alone, companies including Asos and Amazon have been called out by unions for failing to create Covid-19-safe working environments at their warehouses. Brands from Primark to Urban Outfitters faced a public backlash for not fully paying suppliers. The behaviour has sparked a global campaign urging brands to #PayUp.

Fast fashion makes it about newness and scarcity. We have been socially conditioned to love everything that's new.

But consumer outrage is more visible on social media than on the bottom line.

ADVERTISEMENT

Asos’ sales jumped 10 percent over the course of the lockdown compared to the same period a year earlier. Queues of up to 100 shoppers formed outside Primark’s UK stores when they reopened on June 15. Boohoo is already showing signs of recovery; although nowhere near its all-time high of 400p on June 17 this year, its share price was 264.70p at market close on July 21, up from lows of 210p earlier this month.

The scandal embroiling the company still represents one of the greatest reputational tests to hit fashion in years. It’s a potent and toxic mix of alleged human rights abuses, linked to a national disaster in a consumer market. Boohoo has launched an independent investigation into its supply chain, pledged £10 million to weed out malpractice, and fast-tracked a third-party audit of its manufacturers, according to a company statement released July 8. Meanwhile, for many consumers, the allure of a $5 dress remains hard to dampen.

Affordable and Accessible

In fact, the pandemic is likely to deepen the power of affordable fashion. The coronavirus crisis has already plunged the US into recession and seen unemployment levels reach historic highs. Financial hardship is likely to increase the weight consumers give to price rather than environmental and social considerations, particularly when it comes to well-known brands with beguiling newsletters, discounts and easily-accessible online storefronts.

Even before the pandemic, consumers' purported interest in sustainability had a limited impact on their actual spending. Only 7 percent of consumers surveyed in the Global Fashion Agenda's Pulse of The Fashion Industry report 2019 said sustainability was a key deciding factor in making a purchase. Quality, value for money and whether an item made wearers look successful were all significantly more important, the survey found.

“I think the idea that [the Boohoo scandal] is going to spook the whole industry… isn’t exactly right,” said Bernstein analyst Aneesha Sherman. “It’s not a sector-wide veto against fast fashion.”

To be sure, fast fashion players without a strong online presence have been badly hurt by lockdown, but big e-tailers have seen sales soar. Some Boohoo investors have even increased their bet on the company in the wake of its recent scandal. Jupiter Asset Management, Boohoo's largest independent shareholder, upped its stake from 9.6 to 10.1 percent. A representative for Jupiter said the company saw an opportunity in the share price weakness and is continuing to engage with Boohoo on its supply chain investigation.

Innovation is not going to come from new entrants, it's going to come from retailers looking to get ahead of the [curve].

Citibank analyst Adam Cochrane estimates that Boohoo will successfully recover about half of its share price decline in the near term, as the market begins to realise that the scandal hasn’t had a tangible impact on sales.

ADVERTISEMENT

The Instagram Effect

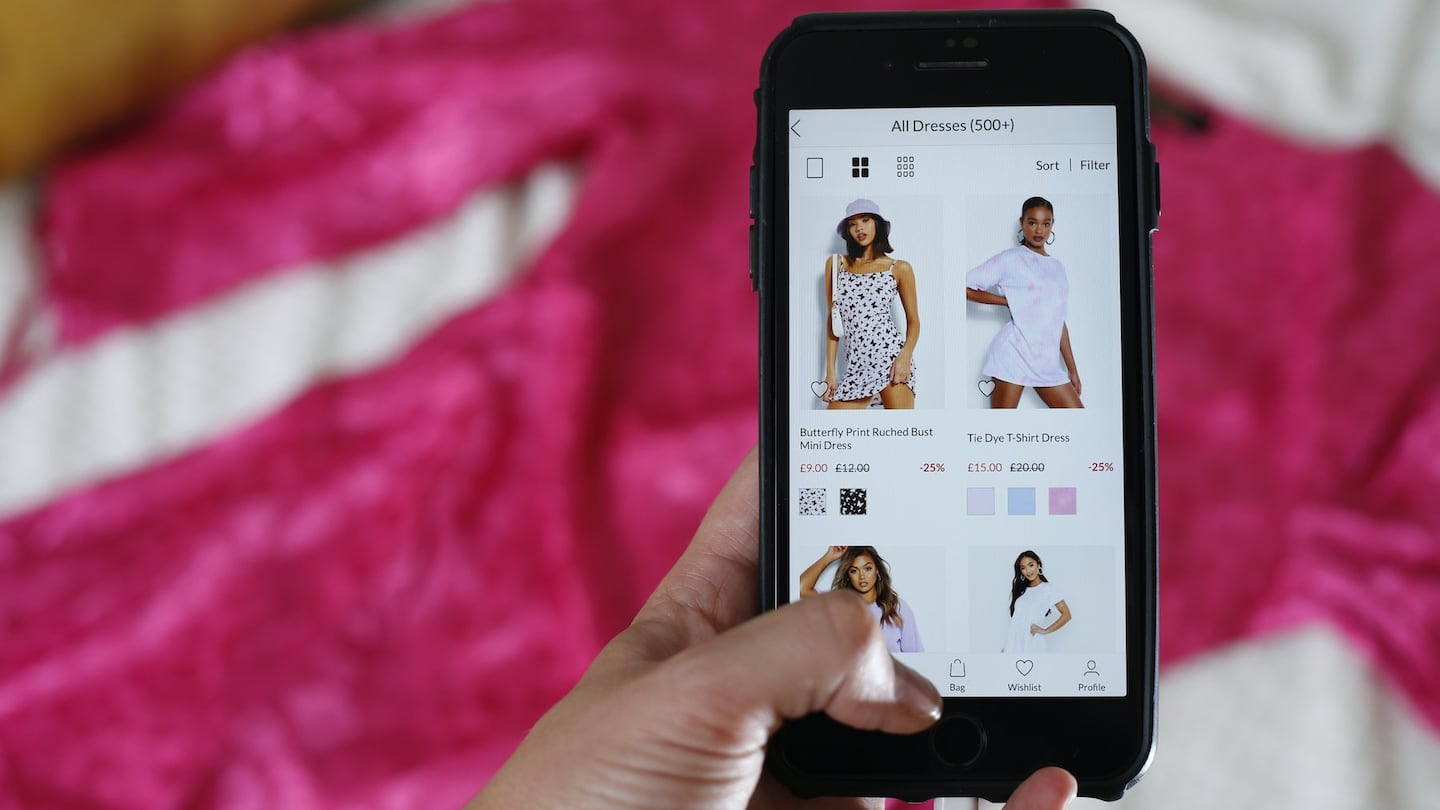

Brands like Zara and H&M firmly established the fast fashion model in the 2000s, offering runway trends at high street prices and a rapid pace. But the advent of social media and online-only players took this model to a new level. A new crop of "ultra-fast fashion" players, such as Boohoo, Fashion Nova and Missguided now offer influencer-led trends at dizzying speed.

“Fast fashion makes it about newness and scarcity. We have been socially conditioned to love everything that’s new,” said Kate Nightingale, founder and head consumer psychologist of Style Psychology Ltd. “We don’t get that necessarily with brands that have new collections every three to six months. Brands have used constant content, newer lines... to fulfil that instant gratification.”

While investors were spooked by Boohoo’s recent scandal, its social media engagement has remained strong. Boohoo’s earned media value (a metric that calculates the monetary value of online user engagement and brand mentions) stands at $5.5 million for the first two weeks of July, well over half the $9.5 million it garnered in June, according to social analytics firm Tribe Dynamics. The company found 643 influencers posted about the brand in the first two weeks of July, compared to 870 for the entire month of June.

The sustained popularity of fast fashion brands boils down to “the agility of these companies, [which means] they are able to move so fast and… adapt to the new reality,” according to Joaquin Villalba, founder and chief executive of retail software company Nextail and formerly head of European logistics operations at Zara.

Social-media savvy fast-fashion brands have also been extremely adept at tapping into powerful networks of influencers and micro-influencers to create a highly engaged community of shoppers.

“People buy relationships not products or services per se,” said Zana Busby, a consumer and business psychologist from consultancy firm Retail Reflections. “What successful brands are doing is... building triangular relationships between brand, influencer and consumer.”

Fashion’s Sustainability Play

ADVERTISEMENT

But while price still seems to trump most other considerations for many consumers, big brands see a growing opportunity in marketing sustainable fashion. capsule collections featuring organic cotton, carbon offsetting and textile recycling have become common initiatives. Experiments in resale, fabric innovation and automation all point to efforts to remain relevant and on the right side of consumer sentiment.

“Innovation is not going to come from new entrants, it’s going to come from retailers looking to get ahead of the [curve],” said Sherman, citing examples such as Zalando’s foray into the resale market and H&M’s adoption of organic cotton and fruit and vegetable fibres for its Conscious Exclusive collection in March last year.

The risk of regulation is mounting, too, amplifying the incentive for brands to lean into consumer demand for products they claim are more ethical. The fact that new allegations of worker mistreatment are entangled with the coronavirus crisis has given a fresh impetus and sense of urgency to the need for political regulation and enforcement. The British Retail Consortium, along with over 90 retailers, more than 50 British MPs and other organisations, have issued a letter to the UK Home Secretary Priti Patel, urging the government to do more to protect employees from exploitation.

Still, the resilience of the fast fashion industry is embedded in the fact that its business model has come to represent an entire price point that consumers are accustomed to.

“There isn’t anything at a mass level at scale that is a viable alternative to fast fashion,” said Sherman. “It’s difficult to get people to stop drinking Coke until you offer them Diet Coke.”

Related Articles:

[ The Big Problems with Fast FashionOpens in new window ]

[ Why Boohoo’s Remarkable Run Came to a Crashing HaltOpens in new window ]

[ Fast Fashion's Biggest Threat Is Faster FashionOpens in new window ]

The fashion industry continues to advance voluntary and unlikely solutions to its plastic problem. Only higher prices will flip the script, writes Kenneth P. Pucker.

The outerwear company is set to start selling wetsuits made in part by harvesting materials from old ones.

Companies like Hermès, Kering and LVMH say they have spent millions to ensure they are sourcing crocodile and snakeskin leathers responsibly. But critics say incidents like the recent smuggling conviction of designer Nancy Gonzalez show loopholes persist despite tightening controls.

Europe’s Parliament has signed off rules that will make brands more accountable for what happens in their supply chains, ban products made with forced labour and set new environmental standards for the design and disposal of products.