The Business of Fashion

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

LONDON, United Kingdom — Inside the warehouses of the newly forming Yoox Net-a-Porter Group is a software-controlled ballet of man and machine. In giant buildings strategically placed near major fashion markets, robots work alongside humans to pick, pack and ship Christian Louboutin stilettos and Saint Laurent biker jackets. It's a reminder that, behind the virtual array of shiny products that populate websites, fashion e-commerce is an intensely physical business, depending on smooth back-end logistics as much as slick front-end experience.

On paper, the merger of Yoox and Net-a-Porter is a perfect union of front- and back-end excellence. Indeed, the all-share deal — in which Yoox is buying Net-a-Porter from Richemont, forming the world's largest fashion e-tailer, with combined annual sales of €1.3 billion — promises to not only deliver economies of scale, but unite two highly complementary companies. Yoox, which began by selling discounted, end-of-season merchandise, is a leader in back-end operations and now powers e-commerce sites for several Kering brands, as well as Armani and Valentino. Meanwhile, Net-a-Porter, which began with full-price merchandise, excels at front-end customer experience, with beautiful packaging, same-day delivery and glossy editorial content. "The two businesses can piggyback on each other now," said Luca Solca, head of luxury goods at Exane BNP Paribas.

Many have noted the sharp differences in the cultures of the two companies, however, not to mention the contrasting management styles of Federico Marchetti, the no-nonsense Italian founder of Yoox and the chief executive officer of the new entity, and Natalie Massenet, the inspirational California-born founder of Net-a-Porter, who tendered a surprise resignation from her role as executive chairman ahead of the merger. "Integrating the two companies will be a challenge. Yoox is a company of engineers. Net-a-Porter is a company of marketers," said Solca. "But it will work, as the set-up is clear. Yoox and Federico Marchetti are in charge. If Net-a-Porter loses one or two pieces in the process, too bad. Richemont seems to have made a very clear decision." (Both Marchetti and Massenet declined to comment for this article.)

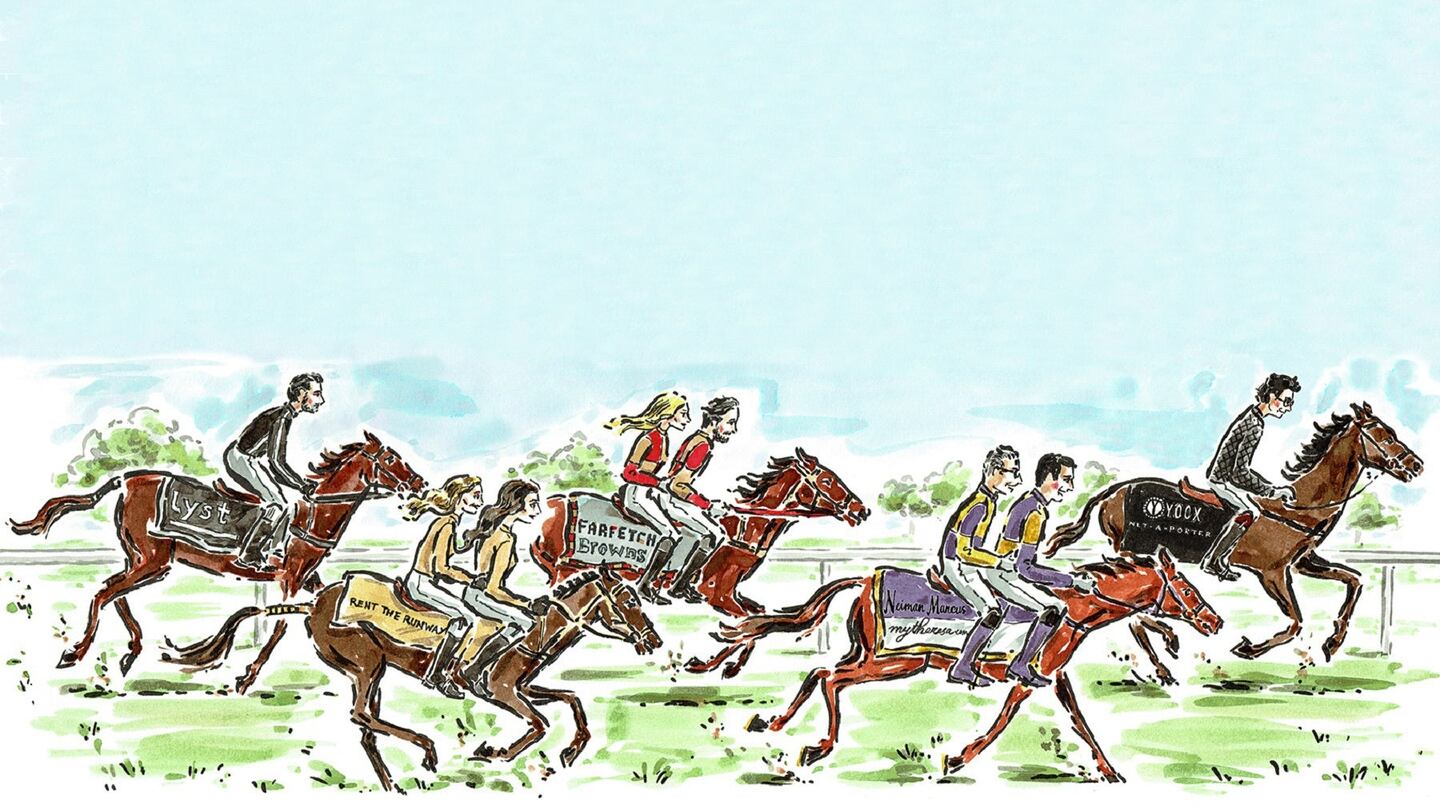

Yet the merger is taking place amidst a fashion e-commerce race that's heating up rapidly, with the rise of new digital business models, management shifts and a string of acquisitions. In the last year alone, American luxury behemoth Neiman Marcus has acquired German fashion e-tailer MyTheresa; billion-dollar fashion 'unicorn' Farfetch has acquired London boutique Browns; Tom and Ruth Chapman, the founders of MatchesFashion.com (a potential acquisition target itself ), have stepped down as joint chief executives, passing the baton to former chief operating officer Ulric Jerome, a technology entrepreneur; Condé Nast has announced plans to relaunch Style.com as an e-commerce site; and 'Netflix for fashion' start-up Rent The Runway, fashion aggregator Lyst and mobile fashion app Spring have all raised new rounds of funding to fuel growth. Indeed, there has been more change in the fashion e-commerce space in recent months than in the last half-decade.

ADVERTISEMENT

PIPES VS PLATFORMS

"The first wave of e-commerce was about bringing the fashion world online. This is what Yoox did. It's also what Natalie [Massenet] did. But we got to a point where it was very fragmented," said Chris Morton, founder of Lyst, a digital shopping mall that aggregates millions of fashion products from brands, department stores and boutiques under one virtual roof. "With Lyst, we looked at the real world and said, look, shopping malls exist. Shopping streets exist. These are very desirable places for consumers to go and for brands to sell. But online, this didn't exist. People were building beautiful boutiques in the middle of a desert," he continued. "We looked at the impact of what Spotify has done to music, what Uber has done to travel. We're aiming to do something similarly impactful with the customer experience in this industry."

For the most part, retailers like Yoox and Net-a-Porter operate a traditional wholesale model, buying and pushing out merchandise to customers. These businesses take on significant inventory risk and have high working capital requirements. Companies like Lyst, on the other hand, are taking a new approach, providing technology platforms that allow certain users (brands and retailers) to display items for other users (shoppers) to consume, without buying and holding inventory. “We build a web platform on top of their inventory,” explained Morton.

But synchronising inventory with retailers in real-time is not without challenges. “Things go in stock, out of stock, things are returned, things go on sale. It really becomes incredibly complex. Half of us are data scientists and engineers,” said Morton. To smooth the customer experience, Lyst has developed a “universal shopping cart,” which allows shoppers to pay for multiple products from different merchants in one transaction. Based on run rate at the time of its latest funding round in April, Lyst is set to hit a gross merchandise volume of $150 million in 2015, up from $77 million last year. (The company takes a “low double-digit” commission on sales, implying actual revenues of much less than that.)

But Lyst is by no means the only fashion start-up making a promising platform play. Farfetch, a marketplace that connects consumers with a global network of boutiques — and, increasingly, brands — recently raised an $86 million Series E funding round in a deal that valued the company at a staggering $1 billion. In early September, Farfetch launched Farfetch Black & White, an independently-run business unit that will leverage the company’s technology and services infrastructure to power e-commerce for brands. According to Farfetch, gross merchandise volume is currently on track to reach more than $500 million this year, putting estimated revenues in the ball park of $125 million. (The business is said to take a 25 percent commission from its current boutique partners.)

Spring is another platform aiming to be a virtual shopping mall for fashion. The company — founded by David and Alan Tisch, along with Ara Katz and Octavian Costache — has created a mobile app that connects consumers directly with brands, which display products in Instagram-like feeds, paying Spring a per-order transaction fee on sales. "People were increasingly using their phones and spending about 85 percent of that time in apps," observed Alan Tisch, chief executive officer of Spring. "But there wasn't enough value for customers to put mono-brand apps on their home screen. They wanted one button to go shopping. They wanted the convenience of a multi-brand experience on their phone," he continued. "At the same time, luxury brands were trying to shift their business model from wholesale distribution to direct-to-consumer. The margins are three to four times higher. Plus, they get to control the brand experience and the data."

“I think the idea of buying inventory has been fundamentally put into question,” said Alan Tisch. “Net-a-Porter is an incredible customer experience, but they are 15 years into their business having barely turned a profit.”

Indeed, for several years, Net- a-Porter did not turn a net profit. But according to recent disclosures, the company generated EBITDA (a measure of operating profit) of £54.2 million (about $82 million) in 2015, up 43.4 percent over 2014, and has been generating positive EBITDA since 2012, before factoring in parent company Richemont’s annual shared services charges and charges linked to share-based compensation for Massenet and the management team.

ADVERTISEMENT

Some also question the advantages of platforms. "I have seen exactly the same battle between Amazon and eBay,” said Michael Kliger, president of MyTheresa, who came to the company from eBay. “Amazon buys merchandise, while eBay is a pure platform. The success of eBay has been based on putting together an enormously deep assortment. But Amazon — because it is in full control, of stock, of processes — can guarantee consistency in payment, packaging, delivery. You can’t do that when you’re a platform.” At the time of the Neiman Marcus acquisition, MyTheresa, which operates a traditional wholesale model, was generating $130 million in annual revenue. The company has been profitable since inception, according to Kliger.

Meanwhile, platforms like Farfetch, Lyst and Spring have yet to turn a profit. What’s more, many of these businesses lack strong brands around which to forge meaningful, non-transactional relationships with consumers. “We're in the middle of planning a significant branding campaign,” said Morton, acknowledging the challenge. “The focus to date has been on functionality. A lot of significant apps, like Spotify and Uber, started in a similar way, first working on the functionality and the customer experience.”

"We very much see ourselves as a brand and not purely a platform," said José Neves, founder of Farfetch. "I agree, it is challenging."

OMNI-CHANNEL REVOLUTION

According to the Boston Consulting Group, online luxury sales are projected to grow 20 to 25 percent over the next five years, compared to only 3 to 4 percent for the luxury industry as a whole, meaning a rising tide for all online fashion players. Yet the vast majority of sales still happen in physical stores. “It’s true that only about 6 percent of sales are online at the moment. But we know that online is responsible for influencing more than 50 percent of buying decisions,” said Neves. “You need to integrate your e-commerce with your physical retail operations.” In May, Farfetch acquired London boutique Browns to serve as a sort of laboratory for testing new omni-channel innovations, before rolling them out across Farfetch’s global network of boutiques, with a total of 1 million square feet of retail space across 30 countries.

"In terms of the Browns acquisition, there are two sides to the strategy," explained Neves. The core Browns business is being run independently and led by Holli Rogers, former fashion director of Net-a-Porter, who joined the company as chief executive officer and plans to refurbish the retailer's South Molton Street and Sloane Street stores. "I also want to open a Browns in East London," she revealed. Meanwhile, what Farfetch calls 'Store of the Future' is being run by new managing director Sandrine Devaux, previously multichannel director of Harvey Nichols. "We really believe that the future of fashion is both physical and digital," said Neves. "Fashion is not downloadable. No one has cracked the formula. But we want to be pioneers."

The omni-channel revolution puts e-tailers which lack physical stores, like Yoox Net-a-Porter, at a disadvantage, while boosting incumbents like Neiman Marcus, which was early to e-commerce, launching online in 1999, and has a network of 41 mainline department stores in major US markets, as well as two Bergdorf Goodman stores. Neiman Marcus recently announced plans to IPO and its S-1 filing with the US Securities and Exchange Commission emphasises its commitment to blending the power of its physical store network with its strength in e-commerce. Indeed, last April, the company united its online and offline activities across several departments.

"Our customers do not differentiate between channels, and now neither will we. These changes allow us to operate as one, single, Neiman Marcus brand," said Karen Katz, president and chief executive officer of Neiman Marcus Group, in a statement issued at the time. (Due to S-1 filing restrictions, Neiman Marcus could not comment for this article.) The company's revenue rose 4.1 percent to $4.84 billion in the fiscal year ended 2 August 2014, with e-commerce accounting for over $1 billion in sales.

ADVERTISEMENT

STREAMING DRESSES

Meanwhile, 'sharing economy' start-up Rent The Runway is challenging the idea of owning fashion altogether with a Netflix-like rental service offering items from brands like Balenciaga. "I saw an opportunity to change a woman's relationship with her wardrobe, where she didn't have to make a lifetime commitment to every article of clothing. Instead, there could be a portion of her closet on constant rotation," said Jennifer Hyman, the company's co-founder and chief executive officer.

Since its inception in 2009, nearly five million women have joined the service and borrowed $300 million worth of dresses and accessories. The company recently launched a subscription product that lets users borrow up to three items at a time for $75 per month. “There's always going to be a place for buying fashion. You will always need great pair of boots, a great coat, a great pair of jeans. But for everything that is adding ‘oomph’ to you wardrobe, you will use subscription products,” said Hyman. “Within five years, it will become normal for women to have a subscription to fashion, just like you have a subscription to music.”

But streaming clothing is much harder than streaming music. “The logistical challenges are immense,” said Hyman. “They involve physically dry cleaning, repairing and restoring garments or pieces of jewellery or bags — and doing that fast. We call it ‘just in time reverse logistics’ whereby everything that is returned to you from a customer in the morning needs to be ready for shipment to another customer by evening.” To manage this, the company has built a high-tech distribution center from scratch. The facility has effectively become the largest dry cleaner in the US. Yet in some ways, Rent The Runway operates like a traditional retailer. “We buy product directly from designers all over the world at wholesale prices. We go to all the fashion shows and place our orders in advance and upfront.”

So between incumbents like Neiman Marcus, traditional e-tailers like Yoox Net-a-Porter and platform players like Farfetch and Lyst, who is best positioned to capitalise on the growing market? “I think we can say incumbents stand the best chance, as they can combine physical and digital capabilities,” said Luca Solca. “Online ‘pure players’ like Yoox Net-a-Porter should be next in line, as they have better control on their offer versus alternative business model players like Lyst and Farfetch.” But there will not be one winner-takes-all model for fashion. “There is not a model that will be the dominant one to destroy the others,” said Mario Ortelli, a senior luxury goods analyst at Sanford C. Berstein.

Neves agreed: “In fashion, you’ve got huge multi-million dollar brands, but you also have thousands of smaller independent designers. The industry has given space to myriad players and, when it comes to technology, it will be exactly the same. Fashion is about individuality. It's about people's tastes. I don't think there's going to be a company that ticks all the boxes for everyone.”

“Rental is a component of how people will look at dressing, as is purchase,” added Hyman. “I think Rent The Runway has a place, I think Net-a-Porter and Neiman Marcus have a place. I think Farfetch has a place. Uber is a very simple use case: ‘I need to get from point A to point B.’ Therefore, one company can dominate. But fashion is too diverse. To think that it will be dominated by one company would be pure arrogance.”

This article appears in BoF's third annual #BoF500 special print edition, celebrating the most influential people shaping the global fashion industry. To order copies for delivery anywhere in the world or locate a stockist, visit shop.businessoffashion.com.

Successful social media acquisitions require keeping both talent and technology in place. Neither is likely to happen in a deal for the Chinese app, writes Dave Lee.

TikTok’s first time sponsoring the glitzy event comes just as the US effectively deemed the company a national security threat under its current ownership, raising complications for Condé Nast and the gala’s other organisers.

BoF Careers provides essential sector insights for fashion's technology and e-commerce professionals this month, to help you decode fashion’s commercial and creative landscape.

The algorithms TikTok relies on for its operations are deemed core to ByteDance overall operations, which would make a sale of the app with algorithms highly unlikely.