The Business of Fashion

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

JAKARTA, Indonesia — "Scared? I was excited," says Svida Alisjahbana from inside her glossy office block overlooking the labyrinth of colonial canals and gridlocked traffic that crisscross this tropical megalopolis. "Back then, the question came up all the time. 'Aren't you worried now that all the international magazines are coming in?' My answer always baffled people. I'd say, 'No, thank God they're on their way.'"

The early 2000s were certainly a critical time for Femina Group and its then commercial director. Svida Alisjahbana was being groomed to take over as chief executive from her formidable aunt and father, who had overseen the company’s stable of titles expand to about a dozen in the course of three decades. Meanwhile, the future of their publishing dynasty was hanging in the balance as rival Indonesian media companies snapped up one juicy international deal after another.

Hearst had just licensed Harper's Bazaar and Cosmopolitan to MRA Group, a move that they'd soon repeat with Esquire. The Indonesian edition of InStyle was then signed over to Kompas Gramedia and, not long afterward, Trinaya Tirta had acquired the rights to Elle and Marie Claire. Competition at the newsstands was becoming cutthroat and the nation's media culture found itself embarking on a whole new course.

By the end of the decade, Indonesia's fashion media mix had swollen to never-before-seen proportions but Femina Group came out of the contest with only one globally resonant fashion title in its portfolio, Grazia. Part of this was probably down to the potential risk of any new international titles cannibalising the firm's similarly-positioned homegrown titles. Yet the fact remained that by not scoring other overseas magazine brands, the group now faced a throng of hungry newcomers out to poach its readers and advertisers.

ADVERTISEMENT

For most of its history, Femina Group had a much firmer grip over the women's fashion and lifestyle market. Thanks to its three powerful flagship titles — Femina, teen counterpart Gadis and their sophisticated sister title Dewi — only a smattering of competitors like Kartini had ever really given the group pause for thought.

Much of this had to do with the politics of the time. President Suharto’s thirty-year military reign had been underpinned by a stranglehold on Indonesia’s media. Policies of censorship and regulation resulted in severe restrictions on foreign publishers entering this vast magazine market that is now the fourth largest in the world (only China, India and the US have more potential readers).

“Despite everything, this period was fortunate for us,” Alisjahbana concedes. “At the time, you needed a permit from the Ministry of Information to operate and they only granted permits to about 100 publications across the board in Indonesia. Frankly speaking, it was a blessing for companies like Femina Group because it let the indigenous magazine market grow and develop first.”

But that era was no more. The floodgates had well and truly opened, allowing in a deluge of foreign competitors. Not only that, Suharto’s downfall also spelled an end to the government’s curbing of domestic competition from upstart Indonesian publishers. For trailblazing companies like Femina Group, this was an assault on all fronts.

So why was a young rookie like Alisjahbana — a mathematics major who had just entered the family fold after a successful stint in financial services — so happy to see these new foreign invaders on her patch? Why indeed when they brought with them a host of enviable resources like valuable global brand cachet, long-running advertiser relationships and access to some of the world’s best editorial talent?

“For the challenge,” she says serenely, as if not quite prepared to reveal just how much she relished it. “We’d already developed an international standard — my aunt and parents had made sure of that — but this meant we had to be a step ahead. We really had to ramp up our capacity to be in the league of the publishing giants of Europe and the States.”

Welcoming the competition as an opportunity to improve, experiment or become more efficient was one thing. But the circumstances of that decade also presented publishers like Femina Group with many other new issues that would force them to up their game. After all, this was a turbulent time for media outlets everywhere.

“It was the heyday of the first cycle of the digital media space when most people were still saying digital was going to kill print — which I hated to hear by the way. Anyway, there we were, having to contend with the convergence of these three things at the same time: the digital phenomenon combined with global expansion and consolidation — and the sudden opening up of our own national media market. So I started redefining and refining. First, by promoting the best of the youngest members of the company up as the older, more resistant generation were, by then, of retirement age.”

ADVERTISEMENT

Back in 1972, when Alisjahbana's father Sofjan first hung a piece of black velvet fabric against the garage door of the family home as a backdrop for the cover of the debut issue of Femina magazine, it was nothing short of revolutionary. The message sent by the composed and utterly chic Indonesian model in a sleeveless maxi dress pictured juggling everything from her daughter, her heart, a mirror, a frying pan and a typewriter couldn't be clearer.

"Women's magazines were nonexistent before that. There was a magazine called Keluarga — or 'Family' in English. But in fact, it was a guide run by men for how women should serve the family. Femina was the first modern women's magazine. My father was the business head and doubled as the photographer. But the first editor was my aunt Mirta Kartohadiprodjo and another inspirational woman, Irma Hardisurya, was the first fashion editor. They featured topics raised by women for women — including fashion of course but much more," says Alisjahbana.

“As a kid, I remember every year, my mother Pia would go away for a month to the fashion weeks in Europe and Hong Kong. Once there, Irma and Pia would blag their way into the runway shows to sketch and review the looks — this was long before catwalk shots could be bought from a photo agency. My mother is small, like me but very sporty and fearless, so she acted as the ‘pusher’ to get them both through the doors. There were very few Asians around fashion week at all back then except the occasional Japanese.”

She adds with the hint of a smirk: “It’s funny because, to say to a Paris fashion publicist in the 1970s that you were a journalist coming from Indonesia — or anywhere from South East Asia for that matter — well, let’s just say that these women needed to have a whole lot of charm and very strong characters.”

The pioneering spirit of Femina was shown once again when Alisjahbana’s mother Pia founded the group’s second magazine a year later, in 1973, an exuberant teenage title called Gadis, as well as in 1991, with the launch of Dewi (meaning ‘Goddess’) which captured the top-end of the women’s fashion magazine market and became a runaway success.

So impressed were luxury brands like Chanel that they began advertising in Dewi from their Singapore territory budget even before there was a media buying budget allocated for Indonesia. And once Louis Vuitton led the way for the first wave of brands to open up Indonesian boutiques in the mid-1990s, these brands too began to partner with Dewi — years before the Indonesian editions of Harper's Bazaar and Tatler even launched.

But for the next decade or so, Femina Group became complacent and began to rest on its laurels — until Alisjahbana saw the rise of digital media as a way to claw back market share from increasingly assertive competitors.

“Moving into digital was an uphill battle,” she sighs. “From the start, I said that there was absolutely no way we were going to divide our editorial teams into print and digital — no way. Every publishers’ conference I attended was saying the exact opposite so imagine how I felt being the lone voice disagreeing with everyone around the world. And internally the older people in management were like, ‘What? You’re going against what all the big international publishers are doing?’”

ADVERTISEMENT

“So I gathered all my new top editors and I told them they would have to become totally platform agnostic. They would no longer be called chief editors. From now on, they would be the chief community officers (CCO) of their respective titles. I think this was quite a radical move considering that Indonesia is usually a few years behind [business trends in] the US. Anyway, now all my editors are officially and personally responsible for their audience in every single channel from print to online to tablet apps to Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Tumblr and whatever else.”

The pay-off has been impressive. Today, Dewi's Twitter community is more than twice the size of Harper's Bazaar Indonesia and Tatler Indonesia combined. Similarly, Femina's Facebook fan base is over three times that of the combined figures for Elle Indonesia and Cosmopolitan Indonesia.

Indonesia’s lack of an independent audit bureau of circulations makes verifying reported print circulation, pageviews and ad revenues impossible. However, analysts agree that, when it comes to online and offline audience figures, each of Femina Group’s key women’s lifestyle glossies are either in pole position or locked in a two-horse race with their closest competitors.

But with international heavyweights still watching from across the border, it can only be a matter of time before the likes of Vogue, GQ and Glamour are tempted to make another foreign incursion. So although Alisjahbana's team of wired and enterprising chief community officers should certainly pause to celebrate, they can't yet afford to claim victory.

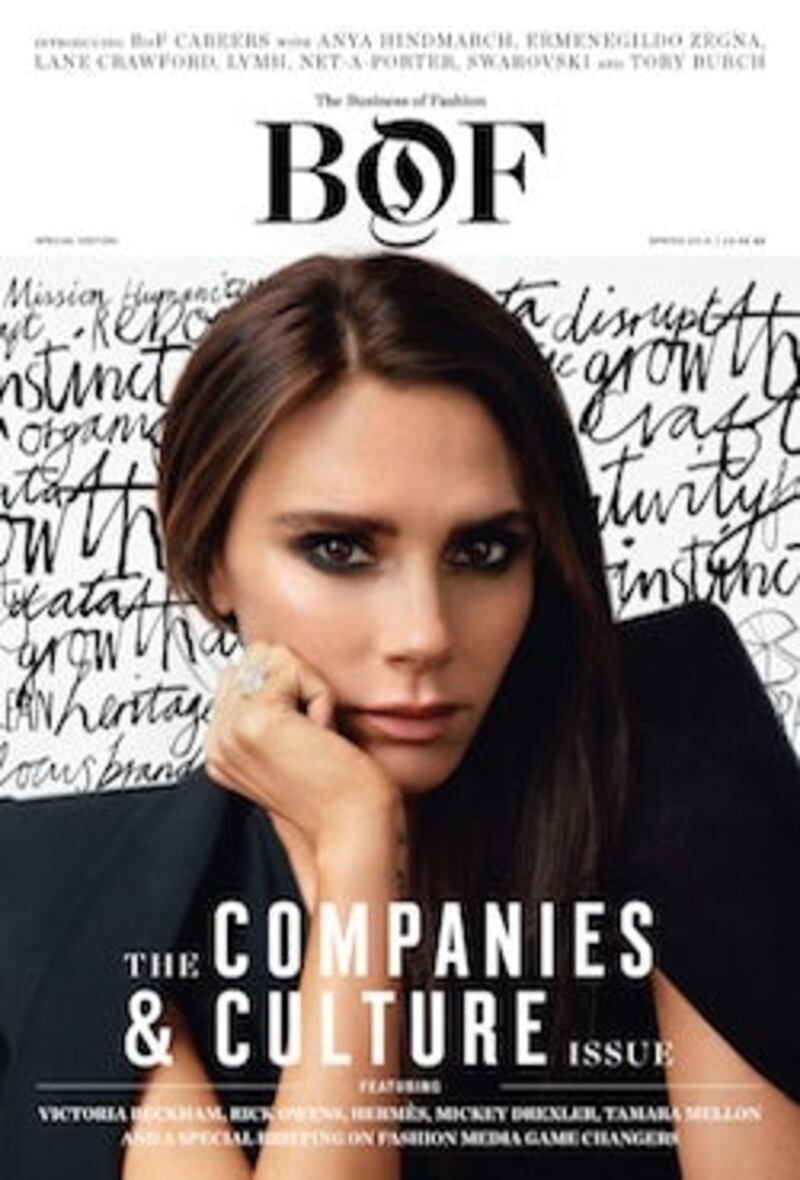

Order your copy of The Companies & Culture Issue, where this article originally appeared, for delivery anywhere in the world at shop.businessoffashion.com, or visit Browns (London), Colette (Paris), 10 Corso Como (Milan), En Inde (New Delhi), Holt Renfrew (Toronto, Vancouver, and Calgary), Lane Crawford (Hong Kong), Le Mill (Mumbai), Liberty (London), L’Éclaireur (Paris), Opening Ceremony (New York and London), and Sneakerboy (Sydney and Melbourne), Wardour News (London), Mulberry Iconic Magazines (New York).

This week’s round-up of global markets fashion business news also features Korean shopping app Ably, Kenya’s second-hand clothing trade and the EU’s bid to curb forced labour in Chinese cotton.

From Viviano Sue to Soshi Otsuki, a new generation of Tokyo-based designers are preparing to make their international breakthrough.

This week’s round-up of global markets fashion business news also features Latin American mall giants, Nigerian craft entrepreneurs and the mixed picture of China’s luxury market.

Resourceful leaders are turning to creative contingency plans in the face of a national energy crisis, crumbling infrastructure, economic stagnation and social unrest.