The Business of Fashion

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

To survive, Diane von Furstenberg had to purge itself.

On the brink of shuttering, the brand, founded by the eponymous designer in 1972 and wholly owned by the von Furstenberg family, laid off more than half of its employees in 2020. It closed 12 out of 13 stores in the US. In desperation, the company was at one point in conversation with Authentic Brands Group, the licensing company known for scooping up dying brands and then aggressively monetising their IP by putting their name on generic products.

After deciding against a sale, Diane von Furstenberg made its most dramatic move yet: It slashed total production by half, effectively erasing about a quarter of revenue.

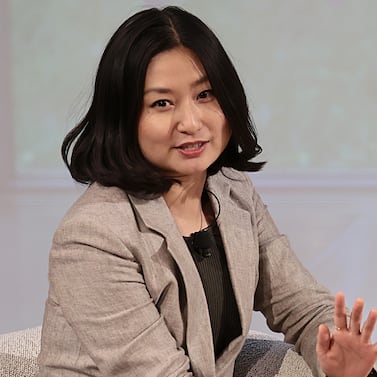

For Gabby Hirata, DVF’s head of Asia-Pacific at the time, it was an unfortunate necessity. After then-chief executive Sandra Campos resigned in the summer of 2020, Hirata was the one who put together the business plan to scale back the top line as well as to make long-time DVF Chinese franchisee owner Jessie Chen a more involved operating partner. Under this arrangement, Chen and the newly formed Glamel Trading Limited would head up manufacturing and merchandising for DVF, as well as employ about half of DVF’s total workforce. When the board approved the plan, the then 31-year-old Hirata became president and acting CEO.

ADVERTISEMENT

“You know what making 50 percent less means? It means less money,” Hirata told BoF.

In hindsight, she added, it was partially her naiveté that lended Hirata the confidence to propose such a draconian measure. But it worked. Last year, DVF generated a profit for the first time in a decade. On top of a healthy profit margin of 10 percent, the brand is on track to moderately grow top line revenue every year. In 2023 and 2024, DVF expects an average global revenue growth target of 15 percent. The goal is to double the company’s previous sales record by 2030.

The designer herself, who took a step back from the business in 2020, said she believes the best is still ahead for DVF the brand.

“When Covid happened, I said, ‘Okay, the world has stopped, let’s take a look at this,’ and I was really contemplating closing it,” Diane von Furstenberg told BoF. “But we somehow managed the impossible”

“It really happened because both of these women [Hirata and Chen] are DVF women,” she added. “They are women in charge and they believe in the brand — our archives of 50,000 prints, a bank of colours, and a dress that’s been selling for 50 years.”

The leadership team, which now includes Diane’s granddaughter Talita von Furstenberg as co-chairwoman, hopes to extend the longevity of the DVF brand. It’s a brand that has survived many iterations, from its origins in the 1970s to a QVC phase in the 1990s and then a revival in the aughts. The company believes that a conservative approach on inventory and a data-driven design process will help DVF slowly but surely thrive again.

“We’re making less money now but more premium dollars, which is the only way for this industry to clean up,” Hirata said.

Diane von Furstenberg became an immediate fashion revelation when the wrap dress first hit the market in the 1970s. The designer’s status as a New York City socialite (and the wife of a German prince) lent an extra halo effect.

ADVERTISEMENT

The decades that followed, however, saw the brand diluted by licensing deals and regular appearances on home shopping networks QVC and HSN.

The relaunch of the wrap dress in the 1990s set in motion a renaissance, turning DVF into a largely wholesale-dependent multi-hundred-million-dollar enterprise under then-CEO Paula Sutter. But in the 2010s, department store began to falter. More options arrived from new brands such as Reformation and Veronica Beard.

“You saw this new batch of brands just taking away our lunch,” said Hirata. “And the distribution became so diversified. You have your department stores, you have your secondhand platforms like The RealReal, and you have all types of e-commerce [shops].”

All the while, workwear became more casual, diminishing the popularity of the wrap dress. Even wholesale accounts became increasingly wary of the brand, because DVF products stopped selling well. By the time Covid-19 struck, DVF was deep in the red, staying afloat through the family’s wealth.

But the pandemic had one saving grace: it gave DVF the time to reset. Ultimately, Diane von Furstenberg decided not to sell her brand when she had the chance. When the pandemic struck, she said, “You had to accept who you are, accept you’re in trouble and that you have to change things, and I did.”

In the time afforded by the pandemic, Hirata and the global leadership team were able to implement a stringent merchandising strategy: on top of limiting the volume of products, she halved the number of styles as well, from roughly 400 SKUs (stock-keeping unit) per season to about 200. There’s now a precise criteria for which styles make the cut that’s based on intensive customer data.

Hirata calls the process “magic and math.” Magic is the artistic force behind the design team, now headed by chief product design officer Sure Liu after a revolving door of creative directors prior to Hirata’s tenure — including acclaimed Scottish designer Jonathan Saunders — and the math evident in the data-forward approach that now informs the design process.

For instance, every piece must fall into one of three buckets: “carryover” styles from prior seasons that sold well in different prints or colour waves, new styles that evolved from successful carryover pieces, and a “test and learn” category of brand new styles.

ADVERTISEMENT

With the latter, the brand treads carefully. “There was a time when we had significant design change,” Hirata said, alluding to the years under Saunders, who overhauled the DVF look to be more elevated and intellectual.

Today, the original DVF look — smart, fitted dresses in graphic prints — is very much alive. Its signature wrap dress is a top-selling style. But the versatile spirit of the wrap dress, according to Talita Von Fursternberg, is now applied to every other product the brand offers.

The DVF wrap dress is successful because it’s “timeless, effortless, professional but also sexy, and easy to throw on,” Talita von Furstenberg said. “Now, we’ve decided that will be our method for every single product we make — multifunctional ease.”

Its new ruched mesh dresses and knit tops (two other best-sellers) are designed to be worn on multiple occasions, from work meetings to date nights. And by ensuring a scarcity of product, there’s less need for markdowns: About 70 percent of all e-commerce purchases are purchased at full retail prices, Hirata said.

DVF now acquires about 3,500 new customers every month. The bigger the company gets, the harder it will be to maintain its stringent inventory control. Maintaining margins, too, will be difficult in the coming months as industry experts expect consumers to pull back on spending.

But Hirata said she’s in no rush to scale the company, which is projected to reach its 2019 revenue in three years. For now and in the foreseeable future, the family has no intention of selling the brand.

“My teams are fighting over inventory right now and we were talking about what the plan is for next year, whether we could make more units,” Hirata said. “Honestly, the answer is no. We don’t know for sure if we can sell them, and it’s just better to be responsible.”

As the company refocuses its prospects on China amid the pandemic, more than 75 percent of the 400-person staff has been let go, while 18 out of 19 stores are closing. But the contemporary brand's business model was challenged long before Covid-19.

In an interview with BoF, the American fashion brand's namesake and recently appointed chief executive Sandra Campos outline plans for a digital, direct-to-consumer push.

Cathaleen Chen is Retail Correspondent at The Business of Fashion. She is based in New York and drives BoF’s coverage of the retail and direct-to-consumer sectors.

The British musician will collaborate with the Swiss brand on a collection of training apparel, and will serve as the face of their first collection to be released in August.

Designer brands including Gucci and Anya Hindmarch have been left millions of pounds out of pocket and some customers will not get refunds after the online fashion site collapsed owing more than £210m last month.

Antitrust enforcers said Tapestry’s acquisition of Capri would raise prices on handbags and accessories in the affordable luxury sector, harming consumers.

As a push to maximise sales of its popular Samba model starts to weigh on its desirability, the German sportswear giant is betting on other retro sneaker styles to tap surging demand for the 1980s ‘Terrace’ look. But fashion cycles come and go, cautions Andrea Felsted.