The Business of Fashion

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

NEW YORK, United States — Forget about fidget spinners. At least for a moment. The real key to unlocking the mystery of Gen-Z is sodium tetraborate... and a bit of white glue. No, these are not the makings of a DIY smoke bomb (or something more sinister). Instead, when mixed together, these two ingredients — and a few droplets of food colouring, if you are so inclined — bloom into a slime: a stretchy, sticky glob that kids aged six to 16 (okay, maybe 15) happily obsess over.

Search for “slime” on YouTube and you’ll generate 16.6 million results. One three-minute “basics” video, posted by 14-year-old influencer JoJo Siwa (3.4 million followers), generated more than 7 million views in a week. Another, posted by the unicorn-loving Gillian Bower (1.5 million followers), promising a candy-coloured swirl of “fluffy” slime, attracted more than 19 million views in just four months. Apparently, the next big thing is sand slime.

Every generation gloms onto a fad—or three—in its youth. For nineties kids, it was slap bracelets; in the aughts, there were Pokémon cards. The fact that Gen-Z is into something so personal, which costs almost nothing to make, speaks volumes about their values.

The generation preceding these slime slingers is nearly as mysterious. To better understand the hive mind of Milliennials, derided as much for their moniker as they are for their preference for rainbow-coloured food, simply ask one of them if he or she maintains a Finstagram — a private, secret-to-most account where the owner can post scenes from “real” life, including unflattering selfies, ice-luge contests and sloppy dinner choices that may be out of line with their personal brands. The challenge, of course, is toggling between Finstagram and Instagram after one-too-many jello shots.

ADVERTISEMENT

Who. Are. These. People? No, really?

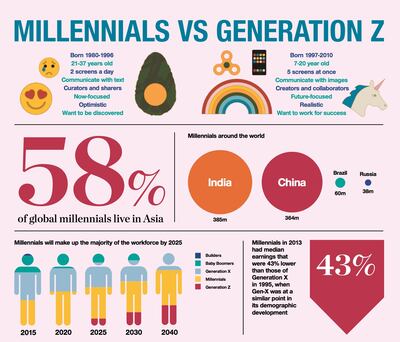

The Pew Research Center, a non-partisan think tank based in Washington, D.C., at one point defined the Millennial generation as those born between 1980 and 1996; Gen-Z starts in 1997 and ends in 2010. Dare to dig deeper and the lines between generations begin to blur. Does the Millennial generation, once called Gen-Y, begin at 1980 or 1981? Is Gen-Z still being born? What’s universally accepted is that, collectively, these two groups represent a powerful force, set to shape the trajectory of consumer culture for years to come in the world’s largest markets, from the US to China, which has its own “post-80s” and “post-90s” generations with mindsets and patterns of behaviour that can vary wildly from their Western counterparts.

Even when I was broke I would spend more money than I had eating out... the thing about Millennials valuing experiences over possessions is true.

About 58 percent of global Millennials live in Asia, including 385 million in India alone. In absolute terms, India, China, the US, Indonesia and Brazil have the world’s largest Millennial populations. But size isn’t everything. For brands seeking to capitalise on the buying power of large Millennial populations, now largely in the workforce, the most important way to measure the scale of the opportunity is a combination of two factors: proportion of Millennials relative to the market’s total population and whether or not these Millennials have good economic prospects. Vietnam, the Philippines, Egypt, South Africa, Iran and India are among the markets which could generate huge potential upside if they can create employment opportunities for their swelling Millennial populations. A.T. Kearney, a management consulting firm, calls them the “Millennial Majors.”

Millennials, Post-Millennials, Gen-Y, Gen-Z... without losing sight of their specific traits, let’s collectively refer to these demographic cohorts as “Generation Next.” Taken together, they are expected to account for 45 percent of the global market for personal luxury goods by 2025, according to Bain & Company. So how can the fashion industry best position itself to capture the contents of their wallets?

America's Next Generation

The United States, still the world’s largest consumer market, is a good place to start. Right now, the luxury brands doing business in the US rely heavily on the Baby Boomer generation, now in their 50s, 60s and 70s, for the majority of spending. For instance, the average age of those who shop at American luxury department store Neiman Marcus is 51. “Peak spending on luxury is typically in the early-to-mid-50s. In the upper 50s and 60s, you start spending less on products in general,” says Steven P Dennis, a retail consultant. “If your customers are aging out, you’ve got to replace them.”

But with whom? In the US, Gen-X, the roughly 81 million Americans who were born before Generation Next, have already slowed their luxury consumption, perhaps due to shifting values; perhaps due to a mindset shaped by three major recessions: one in the early 1990s, another after the dot-com crash, and finally, the Great Recession of the late aughts, which irrevocably changed the way many spend money. For Generation Next, who were children, college students or early-career professionals when the recession hit, a sense of financial instability still pervades their thinking.

Why? Generation Next is the first generation in recent American history to be poorer than their parents. In fact, according to the US Census Bureau, about a third of Americans aged 18 to 34 still live at home. In the US, this is less socially acceptable than elsewhere and often considered a last resort and an indication of failure. And yet, for the first time since 1880, a larger slice of young Americans is living with parents than living alone, with roommates or with a partner. And while home ownership has fallen across the board in the US, it’s falling fastest in the 18-to-34 year-old age group, according to Bank of America Merrill Lynch.

ADVERTISEMENT

“I would fucking love to buy a home and be like, ‘This is where I’m going to die,’” says Crissy Milazzo, a 26-year-old copywriter based in Los Angeles who moonlights penning features for the likes of Vice and Refinery29. “My debt is surmountable at this point because it’s credit card debt, but I just don’t foresee myself having enough to put a down payment on something for like... five years. If I had money, I would be down.”

Some believe that a shift in priorities, not just macro-economic trends, is part of the reason young people like Milazzo can’t afford to buy a home. An Australian real estate mogul — who just so happens to be a Millennial himself — famously took a potshot at his own generation in May 2017 on the country’s version of “60 Minutes.” “When I was trying to buy my first home, I wasn’t buying smashed avocado for $19 and four coffees at $4 each,” said Tim Gurner, a 35-year-old based in Melbourne, Australia. Gurner is in a better position than most of his fellow Millennials — his family loaned him $34,000 to start his own business — but there is a ring of truth to his comment.

Sources | Mary Meeker / KPCB; Pew Research; Kantar Millward Brown; U.S. Census Bureau; Shoppercentric

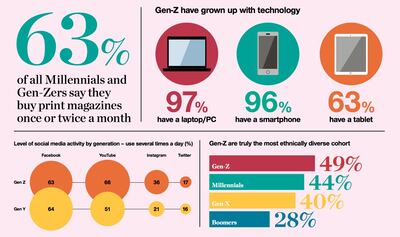

Generation Next are also digital natives, which can be empowering. With the internet at their fingertips, they tend to be highly informed and naturally sceptical. As a result, they are more likely to look up to the makeup tutorials of YouTube stars than traditional beauty advertising. Gen-Z, in particular, prefers advertising that is funny, has good music or tells a story, according to a January 2017 report released by market research firm Kantar Millward Brown, which called the group “highly discriminating” and “more averse” to advertising.

They also prefer to spend money on experiences over possessions. “Spending money on food feels like nothing to me,” says Milazzo, whose current salary is in the mid-five figures. “Even when I was broke I would spend more money than I had eating out, because there’s a social aspect. I do think the thing about Millennials valuing experiences over possessions is true.”

In many ways, Milazzo is the ideal entry-level luxury consumer, a university-educated woman living in LA’s hip and high-rent Silverlake neighbourhood, interested in culture, design and wellbeing. And yet the most expensive piece of clothing she says she owns is a coordinated top and bottom from Revolve that she got as a press gift. “I haven’t bought clothes in so long,” she says. “It’s just not valuable. What’s a valuable thing that actually lasts? A T-shirt is a dumb-ass thing to get from a luxury brand. I could understand designer shoes — they last longer — but there is no justifiable reason to buy a luxury brand’s T-shirt or a luxury brand’s dress.” On the other hand, Milazzo’s live-in boyfriend, a 24-year-old stand-up comedian named Brandon Wardell, would be happy to wear upmarket labels if he could only afford them. “I would buy A.P.C. if I was rich,” says Wardell, whose fast rise on the national comedy scene has been punctuated by drops of his very own “merch”, which has been worn by the likes of Justin Bieber and sold out almost immediately. “When I did the shirts, I hadn’t even been on a TV show and it was pink before ‘Millennial Pink’... Gatekeepers, people that put their thumbs up or thumbs down, matter less,” Wardell adds. “The internet democratises everything.”

All of this may not bode particularly well for the fashion industry, which profits from the conspicuous consumption of expensive goods in a world where displaying social status is becoming more about the accumulation of (Instagrammable) experiences and less about the accumulation of objects. According to fresh data collected in a bespoke July 2017 survey of 769 predominantly female consumers aged 13-34, conducted by Los Angeles-based youth publisher and marketing agency Galore in partnership with The Business of Fashion, 74 percent said they would rather spend their discretionary income on experiences than luxury goods. And yet, while only 54 percent considered owning a luxury brand a marker of success, 85 percent consider craftsmanship to be important and 85 percent see purchasing a luxury item as an investment they can pass down to the next generation.

When it comes to which luxury brands resonate most, young Americans aren't all that different to their predecessors. In the Galore/BoF survey Chanel, Saint Laurent, Gucci and Dior earned top ratings. Balenciaga, Balmain, Prada and Hermès registered as average, while Ferragamo and Coach underperformed. When slicing the results by Millennials and Gen-Z, there were some notable differences. Hermès resonated far more with Millennials, while Gucci scored higher with Gen-Z.

ADVERTISEMENT

China's Post-80s and 90s Generation

No-one can discount the major opportunities for traditional luxury brands in China, whose citizens remain the world’s largest driver of luxury growth. “If we look at emerging-market consumers — let’s say in a country like China — it is 20 times the growth in consumption of that of European Millennials,” said McKinsey senior partner Richard Dobbs in December at VOICES, BoF’s annual gathering for big thinkers.

The way that the Chinese define their younger demographic cohorts, however, highlights a very important point that should give fashion brands pause for thought. The Millennial and Gen-Z concepts popular in the West don’t always translate here.

No-one can discount the major opportunities for traditional luxury brands in China, whose citizens remain the world's largest driver of luxury growth.

According to Martin Guo, editor-in-chief of Kantar China Insights, Millennials and Gen-Z are roughly equivalent to the combination of China’s post-80s generation and its post-90s generation. But citing the profound and rapid socio-economic progress brought about by China’s reform policies over the past 30 years, along with the one-child policy, which has given rise to the “Little Emperor Syndrome”, where only children are the beneficiaries of increased attention and spending from parents and grandparents, Guo believes China’s youth have experiences, mindsets and patterns of behaviour that can be very different to their Western counterparts, especially when it comes to finances. For one, they are not typically saddled with student loans and few have high rent or mortgage expenses thanks to property owned or subsidised by family.

While there are many similarities between China’s post-80s and post-90s generations, there are some aspects where the two diverge significantly, especially when it comes to attitudes towards brands. Guo suggests that the ’80s generation has a higher level of brand loyalty than the ’90s generation and that the ’80s generation is more willing to pay a premium for original and unique brands because they see brands as essential to their identity, whereas the ’90s generation isn’t as committed to that idea.

Yet young Chinese do tend to be less sensitive to price than their Western counterparts, equating expense with high value. According to Daxue Consulting, 48 percent of young Chinese consumers said that they “always pay for the most expensive and best product” within their price range.

But Vogue China editor-in-chief Angelica Cheung cautions that China's younger generations are not to be taken for granted. Much like their Western counterparts, as they invest more and more in experiences and learning, personal improvement and healthy lifestyles, the fashion industry has to work that much harder to attract and sustain their interest. "These are not consumers that are easily influenced by preaching, [so] the way I do Vogue and the way I do Vogue Me is totally different. At Vogue, it's basically, 'I speak, you listen.' And they will listen. That kind of attitude. And with Vogue Me, they speak, I listen, then I try to digest and talk to them in a way that they can understand," said Cheung at BoF's VOICES, referring to a younger edition of the title specifically designed to capture the relatively high spending power of Chinese youth. "It's a totally different generation. You need to know how their mind works and how you influence them and who influences them. It's the 'Me Generation.' It's about my identity, it's about my feelings, it's about how I see the world. They're not just a younger version [of the existing consumer]."

Sources | Mary Meeker / KPCB; Pew Research; Kantar Millward Brown; U.S. Census Bureau; Shoppercentric

Like many of their counterparts across the world, China’s youth also tend to be what older generations might call oversharers, thanks to their love for social media. But beyond WeChat and Weibo, it’s worth considering the impact of Meitu Inc., a Chinese company whose global mobile internet platform makes personal beauty-focused selfie apps that have been installed on over 1.1 billion unique mobile devices around the world.

Meitu’s December 2016 initial public offering made Chinese founders Cai Wensheng and Wu Xinhong billionaires. And the success of the company speaks to several qualities shared by members of Generation Next across the globe. Within one month of releasing a new feature on its “Meitu” face-tuner app, the company saw a 480 percent increase in new users outside of China. To be sure, some of the qualities associated with Meitu’s selfie apps include an obsession with vanity and a desire to conjure a mirage of a perfect life for all the world to see.

Of course, Generation Next is no more perfect — or consistent — than their predecessors, even if their carefully curated social media brands convey they are. Milazzo’s attitude towards fast fashion, at once a saviour and a killjoy for a generation of careful spenders who say they also care about social and envi- ronmental responsibility, sums it up nicely. “I don’t buy stuff at Forever 21 anymore,” she says. “But I still shop at Asos. Those are probably the same thing, right?”

This article appears in BoF's latest special print edition: “Generation Next”. The issue is available for purchase at shop.businessoffashion.com and at select retailers around the world.

Did you know that BoF Professionals receive our print issues first? Annual BoF Professional memberships also include unlimited access to articles, exclusive analysis, invitations to networking events and the members-only app. Not a BoF Professional? Subscribe here.

Related Articles:

[ Luxury’s Generation GapOpens in new window ]

[ Op-Ed | What You Don’t Know About American MillennialsOpens in new window ]

With consumers tightening their belts in China, the battle between global fast fashion brands and local high street giants has intensified.

Investors are bracing for a steep slowdown in luxury sales when luxury companies report their first quarter results, reflecting lacklustre Chinese demand.

The French beauty giant’s two latest deals are part of a wider M&A push by global players to capture a larger slice of the China market, targeting buzzy high-end brands that offer products with distinctive Chinese elements.

Post-Covid spend by US tourists in Europe has surged past 2019 levels. Chinese travellers, by contrast, have largely favoured domestic and regional destinations like Hong Kong, Singapore and Japan.