The Business of Fashion

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

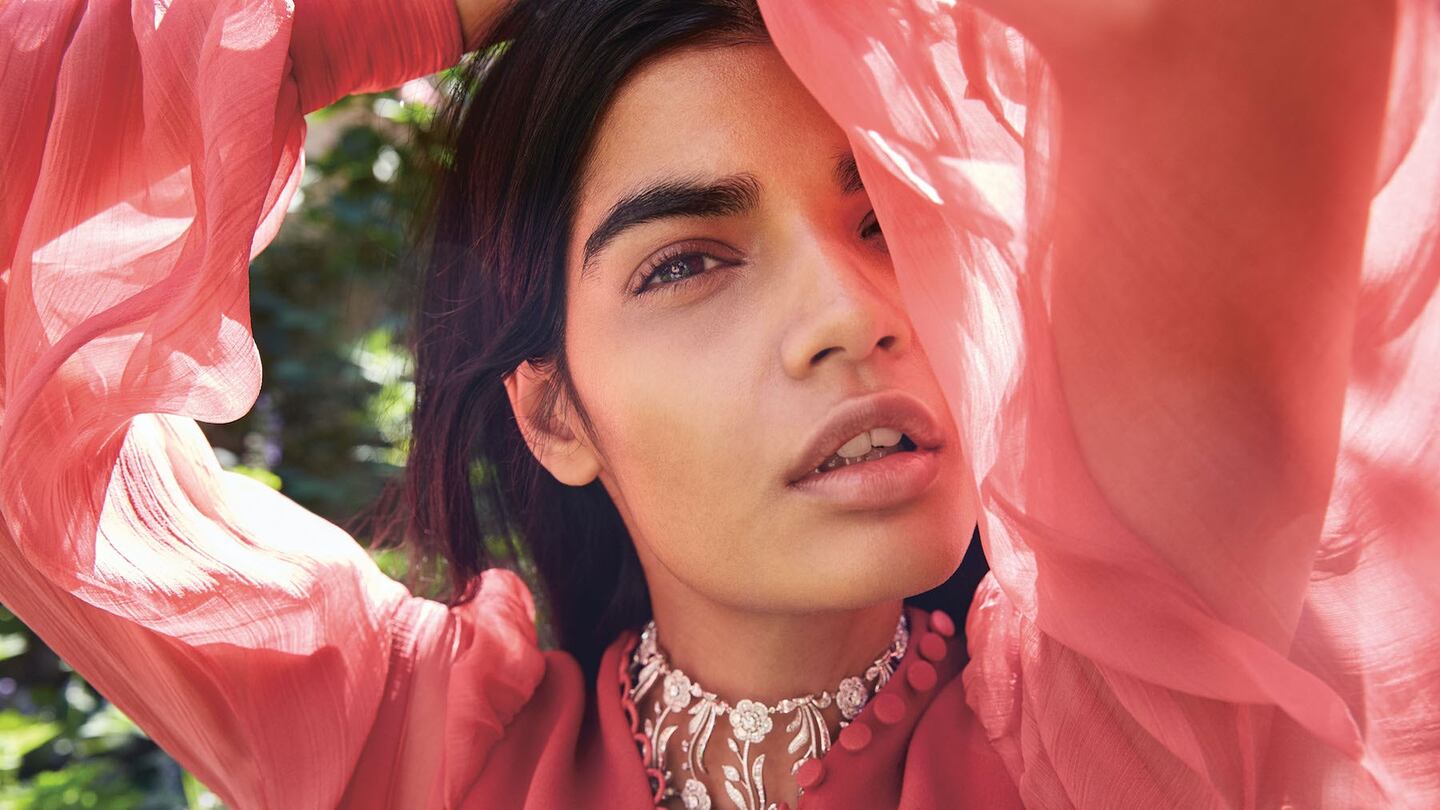

MUMBAI, India — If anything, they look more like beauty barometers than business barometers. Bhumika Arora and Pooja Mor are fast becoming two of the hottest models on the international runway circuit, having caught the eye of megawatt designers like Karl Lagerfeld, Donatella Versace and Marc Jacobs who cast them for recent fashion shows.

But while some celebrate their success as proof of the fashion industry’s long overdue pivot towards greater diversity, rationalists will see something else through the mist of their beauty: the pull of market forces.

The last time Indian models enjoyed a moment this big was 10 years ago when Lakshmi Menon secured a slew of ad campaigns after walking for designers during Paris Fashion Week. Interestingly, that was exactly the same time that Christian Dior and many other luxury brands first entered India with a wave of retail investment and high hopes that the country would become a new engine of growth.

However, the reality never lived up to the expectations, slowed by India’s unique cultural and consumer context along with major structural barriers like the country’s poor infrastructure. And while some now see renewed potential in India’s fashion market — heralded once more by the growing stardom of Indian models — others wonder whether enough has changed to make India a genuine bright spot amidst an otherwise bleak global economic landscape.

ADVERTISEMENT

The fashion industry has good reason to look longingly at the country once again. India’s growth outlook has recently improved on what was an already buoyant forecast. In the coming decade, the economy could swell by as much as 8 to 9 percent per year while more conservative estimates of GDP growth hover around 7 percent. Either way, India remains one of the most conspicuous growth opportunities in a global economy suffering from a slowdown in China, economic crises in Russia and Brazil and widespread uncertainty elsewhere.

But what excites investors more than growth rates is the sheer scale of the Indian opportunity. A recent report by the UN revealed that India, with a current population of around 1.3 billion, is on course to overtake China in just six years to become the world’s most populous consumer market. But in order for this demographic dividend to pay off, the country will have to overcome serious, long-standing obstacles hindering its progress. Endemic poverty among the masses, worrying unemployment rates, haphazard urban development and a creaking infrastructure are just a few.

"India will not be the next China," concedes Darshan Mehta, chief executive of Reliance Brands, a subsidiary of Mukesh Ambani's powerful conglomerate Reliance Industries, which has partnered with international brands like Ermenegildo Zegna and Diesel to tap the Indian market. "Given our very different social, economic and political framework, India will never follow the Chinese trajectory in terms of pace and velocity of growth."

India will never follow the Chinese trajectory in terms of pace and velocity of growth. India will be the next India.

“India will be the next India,” he resolves, likening growth of the Indian market to an oncoming tide, rather than a series of big waves. “It will be steady and rising. Sure, there will be blips along the way [like] a season or two of subdued demand. But [seen] from a 20,000-foot view, the oncoming tide ... will continue for the next few decades.”

Mehta isn’t alone in his upbeat assessment for India and it’s not all about the long term either. In McKinsey’s latest Quarterly Executive Survey, taken in June, 84 percent of Indian executives said they feel optimistic about the country’s economy over the next six months. This is twice as high as executives from anywhere else in the world, including Europe, North America and Asia-Pacific region.

Gradual growth may be the future for the luxury sector but the middle and value end of the market is a lot newer to the country and therefore a lot more dynamic. "There have been some heavy-duty entries into Indian markets in the last two years," says Sahana Sarma, a partner at McKinsey & Co who co-leads the firm's apparel, fashion and luxury goods practice in India. Sarma points to the expansion of affordable chains and high street brands such as H&M, Forever 21, Gap and Inditex's Massimo Dutti among others.

Since launching in Delhi a year ago, H&M has opened five stores across the National Capital Region, an outlet in Bengaluru and one more in Mohali, a city adjacent to Chandigarh. There is so much excitement about the fast fashion brand that in August, 1,500 people waited in queues outside High Street Phoenix for the opening of its first outlet in Mumbai — some for more than 30 hours to secure discount coupons for a bargain on their first H&M purchase. The brand is said to be targeting a footprint of 30 Indian stores within five years’ time, reflecting an investment of around $130 million.

Unlike H&M, whose late arrival to the market was complicated by its decision to opt for a wholly-owned subsidiary structure, Zara touched down six years ago through a joint venture between its parent company Inditex and Trent, the retail arm of India’s Tata Group. Zara’s India unit reportedly earned revenues of over $100 million last year, a new high in the category for the country, from just under 20 Indian stores.

ADVERTISEMENT

No wonder. Sales of apparel and footwear in India grew 14.4 percent annually from 2010 to 2015, according to data from Euromonitor International. Today, the Indian fashion market is worth $67 billion, making it as valuable as the combined size of 15 of the biggest Middle Eastern countries, or about a fifth the size of the US or China. By 2020, it should reach $88 billion.

“We’re very optimistic that the apparel market is expected to grow well — and faster than the overall economy,” says Sarma from McKinsey’s Mumbai office. Among other factors, she cites a greater awareness of Western brands and greater numbers of Indian consumers who are “willing to spend beyond basic needs and on a broader set of occasions,” and also a growing movement “towards Western and casual wear.”

Crowds in New Delhi at the opening of H&M's first store in India | Source: Courtesy

This is a significant change in behaviour, as more and more urbanised Indians are wearing Western — not Indian — clothes on a day-to-day basis, although Indian clothes remain the default for special occasions. As a result, India’s own high street players — such as Pantaloons and Cover Story, a new brand in Kishore Biyani’s Future Group portfolio — are feeling energised and competitive. Local brands like these have a much better understanding of the market’s tastes, trends, ethnic wear silhouettes and the vast repertoire of Indian clothing traditions.

The number of Indians able to afford branded fashion is set to quadruple in the next five years. According to an Ernst & Young report on the global middle classes, about 50 million Indians, or 5 percent of its population, earn between $10 and $100 per day now. The firm forecasts that it should reach 200 million by 2020 and 475 million people by 2030.

However, most of India’s wealth remains very unevenly distributed. Around 90 percent of the adult population falls in the bottom of the wealth pyramid earning less than $10,000 per year, with many millions still in abject poverty. On the other hand, India’s rich are rising fast in the global rankings. Only 10 countries worldwide have more millionaires (HNWIs) than India and only three countries have more billionaires, namely the USA, China and the UK.

"There are many Indias," quips Condé Nast India's chief executive Alex Kuruvilla. "And this diversity needs to be captured and reflected in everything, [not only in retail but] editorially too."

“Since our launch of Vogue and GQ India, we’ve aimed to capture the fascinating diversity and taste of the Indian consumer. Editorial coverage has to balance many elements — old money and new, young and old, traditional and contemporary, Western and Indian, national and regional, high fashion and high street and our editorial content reflects these dualities. You need to be at once aspirational and accessible,” he explains.

ADVERTISEMENT

“For instance, we cover international fashion runways but our trend reports have to decode this for the Indian woman or man. This is why 90 percent of our editorial content is locally produced. [Brands often need to] create India-specific ad campaigns; use local faces. [In India, you have to] localise, localise, localise.”

Naturally, this extends to design and product development too. A couple of years ago, Hermès offered a made-to-order sari and Canali released a bandhgala suit, but they seem a drop in the ocean. Few Western brands adapt their ranges to the Indian market beyond an edit of existing international collections.

This explains why Indian designers like Sabyasachi Mukherjee and Manish Malhotra can operate vibrant, lucrative businesses. For special occasions like weddings and festivals, Indian attire is a must. At the more affordable end of the market, the lack of a tailored offering by Western brands can be advantageous for more experienced operators from the Indian diaspora like Micky and Renuka Jagtiani's Landmark Group in Dubai, which penetrated the subcontinent much earlier through its price-conscious chain Max.

Global brands also struggle to keep pace with the Indian market due to the ongoing shortage of quality retail space. It’s true that several notable shopping centres have been built in the past 18 months, such as Bengaluru’s VR Mall, Kolkata’s Acropolis Mall and the giant DLF Mall of India covering nearly 2 million square feet in Noida outside Delhi. However, retail experts at A.T. Kearney estimate that India only has 10 percent the mall space of the US, even though India’s population is four times bigger.

For the country’s dynamic and increasingly aggressive online fashion players, herein lies a golden opportunity. The sluggish development of brick and mortar and formal retail districts makes the need for e-commerce all the more urgent. Even when there is suitable space available, high rents and complex regulations make a digital-first route to market an attractive option. Topshop finally arrived in India last year when it partnered with local e-tail juggernaut Jabong.com.

E-commerce is clearly here to stay and grow and change the way Indian consumers buy.

“Jeff Bezos has already committed $5 billion and the Indian players are responding with vigour. The result is the creation of a completely new ecosystem that will overcome many of the historical challenges that plagued the industry,” says Kuruvilla, referring to a recent pledge made by the founder of Amazon to invest further in its Indian operations.

Euromonitor expects e-commerce to post the fastest sales growth of all fashion distribution channels in India over the next decade. The potential is quite remarkable given that the total number of Internet users in India was already 350 million people last year but that this represented only 30 percent of the population. Consider too that India is the second largest smartphone market in the world, ahead of the US and behind China.

Last year, Google India’s director of e-commerce and online Nitin Bawankule put the opportunity into sharp relief when he spoke at an industry event. “By 2020, India is expected to generate $100 billion worth of online retail revenue, out of which $35 billion will be through fashion e-commerce. Online apparel sales are set to grow four times in coming years,” he said.

General merchandise sites and pure-play fashion verticals alike emerged out of India a few years ago but the sector has since undergone a major consolidation that saw Flipkart acquire Myntra and Jabong.

But what of recent reports suggesting that India’s online market is cooling down due to a cash crunch and inflated valuations?

“The current valuation decline is more of a correction due to the over-heating of the sector but e-commerce is clearly here to stay and grow and change the way Indian consumers buy,” Kuruvilla explains.

Yet some industry observers are decidedly less bullish about India’s much ballyhooed luxury market. Federica Levato, a partner and co-author of Bain & Co’s annual luxury goods report says that most major luxury brands have no more than five or six physical stores in India, with a few closer to 10. India’s luxury market “won’t be moving in 2016 [because] we don’t see any big declarations of new luxury store openings,” she says, suggesting that some of the focus on India is about image.

“Now that most global luxury markets are flat or not increasing dramatically, they have to focus press attention on the few markets where there might be potential growth like India,” she says.

The head representative of LVMH in Asia, Tikka Shatrujit Singh, who helms the group's brands on the subcontinent, agrees. "The decline of China has triggered this new interest in India. To cover the shortfall," he says.

But if anyone else has a grip on the health of India's luxury market reality, it is Sanjay Kapoor, the founder of luxury conglomerate Genesis Colors which owns upmarket sari brand Satya Paul and distributes Giorgio Armani, Jimmy Choo, Michael Kors, Coach and other brands through 120 mono-brand, multi-brand and shop-in-shop stores across India.

“We’ve had a fairly good run over the last decade with same store sales growing at approximately 15 to 20 percent year on year,” says Kapoor, who points to Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s introduction of a GST (Goods & Service Tax), the kind of economic reform that he feels bodes well for the industry.

Vogue India | Source: Courtesy

LVMH’s Singh concedes that the government has been slow to make reforms, but he says it’s a matter of time before they take more decisive action. “Modi is pro-business but I just don’t think his priority is the luxury sector now. It doesn’t really provide jobs in the way and scale that the government needs,” he says. “But if you can make a case [against excessive bureaucracy], his government can be receptive and quick to implement change. The new ministers are more progressive.”

The government’s restrictions on FDI (foreign direct investment) have been a major dampener on the luxury market for years. “[These have] eased up. However, there are stipulations or conditions to the 100 percent FDI in single brand retail, which impacts fashion and apparel players most,” says McKinsey’s Sarma, explaining how this has compelled some foreign luxury brands to hold back expansion plans.

“FDI in single brand [companies] stipulates that for 50 percent and above, the multinational corporation needs to take approval from the government and for above 51 percent it also needs to source 30 percent of the value of goods purchased from India — preferably from MSMEs (micro, small and medium enterprises), village and cottage industries, artisans and craftsmen,” Sarma says.

Rather than owning just a minority stake in their Indian unit through a joint venture with an Indian partner, many global firms prefer 100 percent ownership without such stipulations.

This isn’t the only major barrier that foreign brands face. India is still cited as a difficult place for overseas investors to do business, with a lack of transparency in several parts of the economy and a high start-up cost.

Prime Minister Modi’s crackdown on corruption has however gained some momentum, as seen by last week’s shock announcement to demonetise large rupee bills. The controversial move to replace large denomination notes is designed to bring billions of dollars' worth of ‘black money’ cash into the formal economy.

But for Kapoor, the main ongoing drag on growth in the sector is insufficient luxury retail infrastructure — a long-term issue that has still not been satisfactorily addressed. “That’s the one impediment brands in our portfolio currently face for rapid expansion. All other issues — FDI, import duties and internal taxation — they’re only secondary,” he says.

Nevertheless, Kapoor cites growth opportunities in cities like Bengaluru, Hyderabad, Kolkata and Chennai after serving the most important luxury markets of Delhi and Mumbai. “So far, these cities are equipped to house luxury brands [but] the infrastructure outside is still lacking,” he says, identifying Ludhiana, Pune, Ahmedabad, Surat, Kanpur and Indore as “good feeder cities.”

“A lot of new developments are on the anvil where brands are looking at the next level of expansion. Some of the key ones that should open by next year are The Palladium in Chennai and the Reliance Mall in Mumbai,” he says.

According to LVMH’s Singh, one of the reasons for the luxury retail space shortage is that there has been a disconnect between foreign brands and Indian developers in terms of zoning and architecture expectations. “[New Delhi’s DLF] Emporio Mall got it right because they started discussions with brands while they were designing the mall,” he says.

India is a long term play, you can't expect short term results.

Another dampener is that foreign brands are still treating the Indian luxury market as if it is only an accessories play, with very small ready-to-wear assortments in their boutiques.

“Yes, some brands have needed to invite wealthy Indian women to experience the catwalk shows abroad to show them how to do it [but] younger Indian women already adapt to [Western clothing silhouettes] easily; they’re going to the gym; they’re a different generation. So whichever brand invests now will win them over,” he says.

“Apart from price, that’s also why wealthy Indians buy a lot while travelling overseas — selection. Imagine when you take 500 people to Vienna or Venice for a wedding, for example. The shopping they do abroad is huge,” he adds.

Indeed, Global Blue has seen a 13 percent increase in tax free shopping abroad by Indians year-on-year June 2016, and expects 50 million outbound Indian tourists by 2020.

As far as Mehta is concerned, luxury brand executives have no one to blame but themselves for their weak exposure to the market. He traces it back seven years ago when many entered. “A few people became poster boys heralding an oncoming avalanche of luxury consumption [but] their exuberance was irrational,” he says “So was the cry of a ‘bust’ by the same poster boys just 18 months later when they started talking about all that was wrong with India.”

Kapoor says that those luxury players who feel disappointed by their last 10 years in India need to see the market from a long term perspective.

Singh agrees: “India is a long term play, you can’t expect short term results. India is a young market and it’s the last big luxury frontier. But many brands in our industry have shied away and not committed enough investment.”

“They’ve missed out on a massive opportunity so far, and why? None of the top brass really understands India; some still haven’t even come to India to see with their own eyes. And few of the others understand the local conditions like they should,” Singh bemoans.

“Here’s this incredible market waiting to be seduced but they’re sitting at home asleep. It’s astounding.”

Related Articles:

[ H&M’s Next Target: The Indian Middle Class Opens in new window ]

[ India, the Fashion World's Next Manufacturing Powerhouse?Opens in new window ]

This article first appeared in The Business of Fashion's fourth annual BoF 500 special print edition, which includes stories on Kate Moss, Tory Burch and Tadashi Yanai, as well as a collectible directory of the people shaping the global fashion industry in 2016. Click here to order your copy.

This week’s round-up of global markets fashion business news also features Latin American mall giants, Nigerian craft entrepreneurs and the mixed picture of China’s luxury market.

Resourceful leaders are turning to creative contingency plans in the face of a national energy crisis, crumbling infrastructure, economic stagnation and social unrest.

This week’s round-up of global markets fashion business news also features the China Duty Free Group, Uniqlo’s Japanese owner and a pan-African e-commerce platform in Côte d’Ivoire.

Affluent members of the Indian diaspora are underserved by fashion retailers, but dedicated e-commerce sites are not a silver bullet for Indian designers aiming to reach them.