The Business of Fashion

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

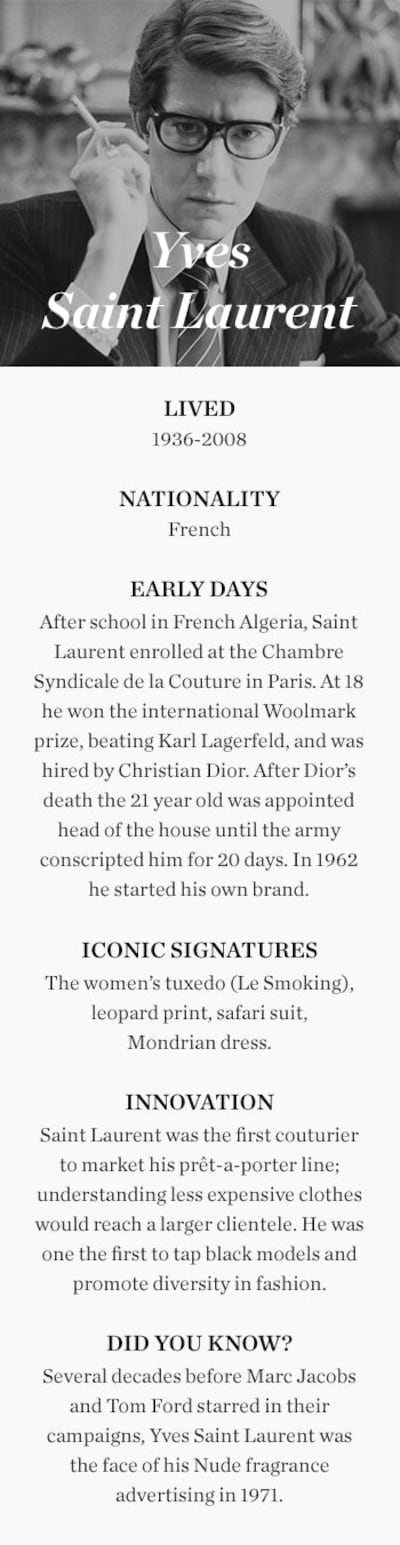

PARIS, France — Yves Henri Donat Mathieu Saint Laurent was the founding figure for modernity in fashion. When he retired in 2002, he could look back over his years as a designer and, with perfect justification, claim not only that every major change in women’s dress had originated with him, but also that many current female attitudes were, in part, the result of his uncompromisingly bold fashion approaches, not least to self and sexuality.

Born in Oran, Algeria in 1936 into a well off family, Saint Laurent's gentleness, timidity, and the fact that he was a homosexual in a macho culture made him a prey to bullying and, inevitably, made him turn in on himself. Sad for him of course, but invaluable for his future. He created his own world with a fashion house complete in every detail and all made out of cut paper. His imaginary fashion house, Yves Mathieu Saint Laurent haute couture was based in Place Vendome. His models were cut out of his mother's fashion magazines and he dressed them with his own designs for clothes and accessories. The models were called Bettina Graziani and Suzy Parker, their hair was by Carita and makeup was Elizabeth Arden. The suppliers of fabric, furs, shoes and jewellery were all world-class manufacturers. The clients were played by his two sisters. He was totally obsessive.

In his late teens he did waver in his dream of being a couturier, wondering whether or not he should be a costume designer instead. Fashion won out, but throughout his life as a couturier he also designed costumes for theatre, film and ballet, working with people of the calibre of the film directors Bunuel and Truffaut; actresses Jeanne Moreau and Catherine Deneuve and the ballet dancers Roland Petit and Rene Jeanmarie. There can be no question that Saint Laurent had a broader base than any of his contemporaries working in high fashion in what, with justification, can be called the YSL years.

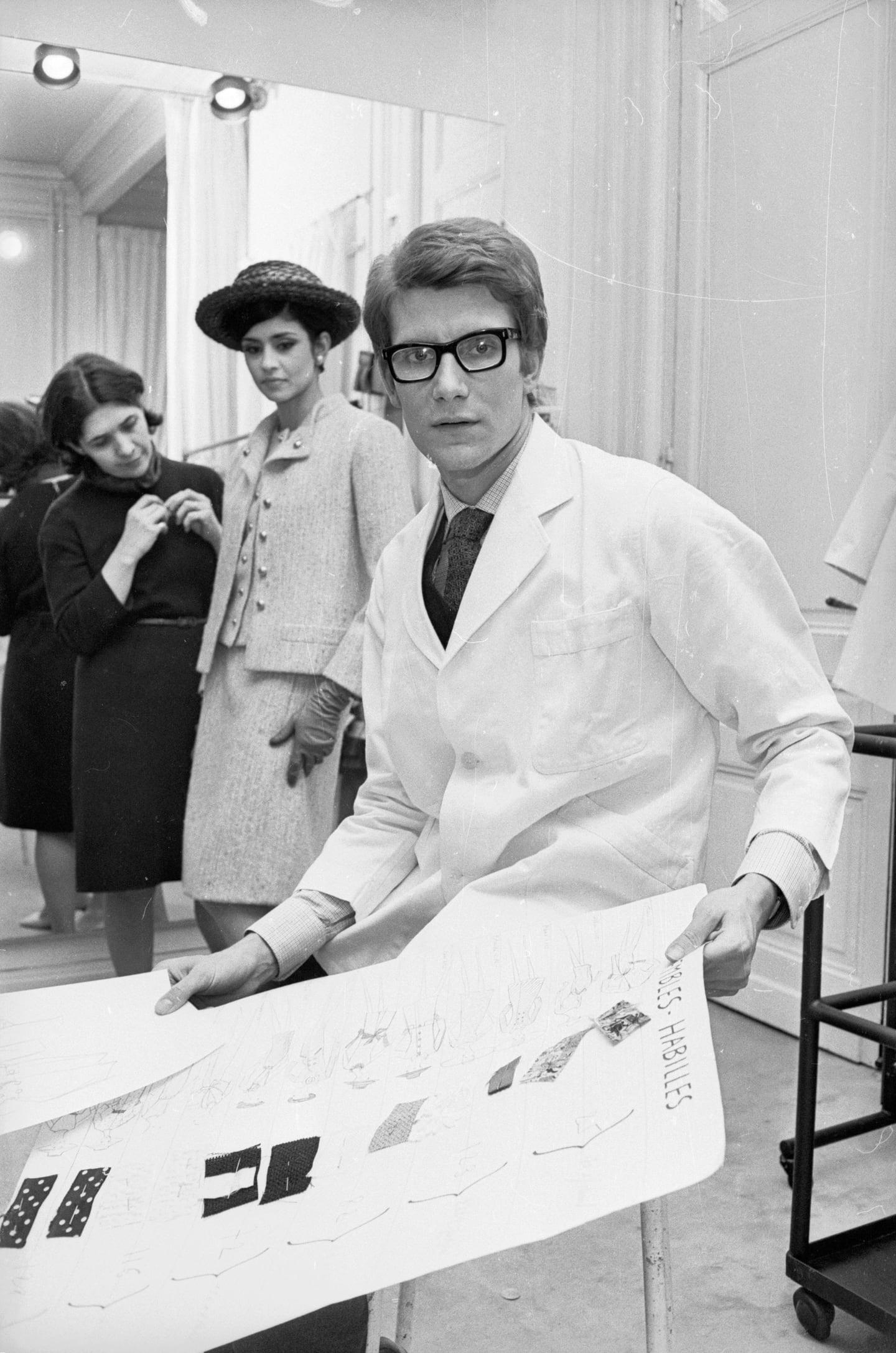

Those years began in 1955 when, advised by Michel de Brunhoff, the editor-in-chief of French Vogue, Christian Dior took him on as his assistant at his eponymous fashion house, the most famous in the world at that point. But Saint Laurent had already proved his ability by winning three of the International Wool Secretariat Prize categories the previous year, with Karl Lagerfeld winning the fourth. At Dior he made his mark quickly: his evening dress worn by Dovima while standing between two elephants, photographed by Richard Avedon, commanded attention. So, when Dior died suddenly in 1957, it came as no surprise to Paris when Saint Laurent took over the house. His first collection was a great success, as it was entirely in the spirit of the Dior aesthetic. But then things began to go wrong. Either through youthful arrogance or over-enthusiasm, subsequent collections were pitched far too young for the average Dior customer.

ADVERTISEMENT

Boardroom concerns and seriously diminishing sales figures resulted in a very public sacking of the man who, such a short time before, had been publicly hailed as the saviour of French couture.

The news went around the globe in arguably the first time that a fashion designer had commanded the front pages of the world's press, including those who considered that women's fashion and all its doings should be confined to the women's pages. The intense media interest made him world famous. He was 21. But the exposure contributed to a nervous breakdown. His mental state was not helped by the fact he had been drafted into the French army, the emotional equivalent of putting a fawn into an enclosure with a hyena. Medicines and treatments for nervous illness were in their infancy and almost certainly did more harm than good. He was discharged.

Pierre Bergé, an unlikely fairy godmother in many respects, but a man with a very good brain and a determination that could not be budged, was already Yves’ lover — a relationship that lasted until the designer’s death. He took over the business side and set out to re-establish his lover's name. An entrepreneur, he had made his previous lover, the artist Bernard Buffet, a major figure in Parisian art circles and he knew he could do the same for Yves. He and Saint Laurent had such strong conviction, they were able to convince Dior colleagues, including Claude Licard, who became head of the design studio, Gabrielle Buchaert, who was press officer and the mannequin, Victoire, to join them. The YSL logo was designed by Cassandre, the world's greatest graphic designer of the time, and the enterprise was underwritten by J. Mack Robinson, an American entrepreneur, to the tune of $7,000. The miraculous birth had taken place, despite the doubts of many intelligent observers in Paris and further afield who worried about the longevity of the relationship of the two men and the mental health of Saint Laurent.

Yves Saint Laurent, now allowed to use his imagination and deeply felt opinions on how modern women should dress, knew precisely what path he intended to follow. He wanted to continue the elegance that he had learned with Dior and which had won him the coveted Neiman Marcus prize for Trapeze, his first collection at the helm after Dior's demise. But he was streetwise enough to know that beautiful as such elegance was — especially when photographed by a top photographer – it had little beyond aesthetic appeal for the women for whom he was determined to open up the prospect of a modern elegance which was not only beautiful but also wearable.

It is salutary, before looking at Yves’ years of success, to examine what went wrong at Dior. Firstly, of course, Saint Laurent was put in charge of a company that totally reflected Dior's personal approach to fashion which, 10 years after the New Look, appeared to many, if not tired, then certainly academic as far as the high street was concerned. Yves knew this and, after Trapeze, he decided to bring the age level down dramatically. Although customers had raved over the Trapeze collection, their reaction to the next two collections, “Arc” and “Longline,” was more muted. But it was his Beat Look that destroyed their trust. Although Saint-Germain adored it, few who hung out there could afford anything that came down the runway — the mink-lined black crocodile bikers jacket, which looked fabulous in photographs, probably cost more than most of their annual salaries — and those who could afford it felt that street styles were simply not couture — and certainly not wearable by anyone over 25. Such clothes made no money for the company. And it must be said that, unlike today, when avant-garde couture is created with virtually no interest in pleasing anyone but the press, couture in the early sixties was still made to be sold and worn by customers.

However, Yves and Berge knew that if their new company was to survive there was a need to sell something to keep its supporters happy and also excite the press. In one amazing moment of the foresight that punctuated much of Saint Laurent's working life, he turned his back on the Dior days. Putting on his cultural hat and wishing to do something accessible enough for the high street, he made a series of woollen shifts inspired by the twenties Dutch artist, Piet Mondrian. Simple, clean and dramatic they bought fashion design in line with fine art, product design and all the aspects of early 20th century attitudes, in that they were totally functional and, unfortunately, easily and cheaply copied. But for publicity they were perfect. They caused a sensation and put him in pole position across the globe at the head of the few designers in Paris who understood the new informality of the modern woman's life.

On a roll, he plundered pop culture, primitive societies and the work of the great artists in a series of groundbreaking concepts: Pop Art, Africa, Safari, Morocco, Ballets Russes, Chinoiserie, Matisse, Braque, Picasso, tuxedos, and Le Smoking. His breadth of imagination and his boldness of interpretation were staggering. One fashion commentator hailed his designs as milestones of fashion history but, magnificent and unique as his couture collections were, his ready-to-wear continued to reflect the needs of the street and the relaxed approaches to individuality, sexual freedom and the growth in female power and self-esteem. If, as has been claimed, Chanel is credited with "inventing the 20th century" for women, Yves can be claimed to have invented the force of individuality, regardless of sex or colour. The trouser suit, the smoking, and the Safari jacket are staples of the fashion lexicon of women everywhere. Saint Laurent once made his own list of the things he liked most out of all the things he had done for women, pointing out that so many of them were adapted from the masculine wardrobe, including the blazer, the trench, shorts, safari jackets and trousers.

And, of course, there are the fragrances and the boldness of their conception and presentation, where Yves Saint Laurent once again was a trail blazer. In 1971 he posed nude for what has become a talismanic portrait by Jeanloup Sieff to publicise the first YSL for Men fragrance, only two years after his Rive Gauche men's clothing range was launched. But, of course, he didn't always walk on water. In the same year as the portrait, he created a scandal with his 40s collection. It was universally condemned as a serious failure of taste, showing a cruel indifference to the plight of people in Paris during the Nazi occupation, many of whom were still alive and remembered the privations such as eating rats in order to keep alive. But again, Yves’ luck came to the fore.

ADVERTISEMENT

Although most of the commentators of the time were blind to it, the collection bought style to the original badly-made and pre-fabricated ‘40s original garments and the short imitation fur coat and turban in bright grass green has become a classic revived by other designers on a regular basis.

Pierre Bergé, said two telling things about his partner. The first is very well known as it is frequently resurrected: “Yves was born with a nervous breakdown!” It is an amusing, throwaway remark. But the second goes deeper. It describes Yves as “a man of exceptional intelligence, practising the trade of an imbecile,” and it raises the question: despite his immense and still-continuing influence on fashion, could he have been an even greater artist?

There have been good designers in the past. Many of them have been greatly important in the little niche they have created for themselves. There are many who, like Vionnet and Madame Grès, impacted the very idea of what cloth could be used to achieve. But none of them had the over-riding authority to set the highest standards for fashion over many years and to change not only how we dress, but also how we think of ourselves, whilst posing the challenge of excellence to mode designers.

Yves Saint Laurent was the Janus of fashion who looked back at what had gone and forward to what might be. His influence is with us still and his place in the pantheon of creativity is unlikely to change until fashion itself does.

From analysis of the global fashion and beauty industries to career and personal advice, BoF’s founder and CEO, Imran Amed, will be answering your questions on Sunday, February 18, 2024 during London Fashion Week.

The State of Fashion 2024 breaks down the 10 themes that will define the industry in the year ahead.

Imran Amed reviews the most important fashion stories of the year and shares his predictions on what this means for the industry in 2024.

After three days of inspiring talks, guests closed out BoF’s gathering for big thinkers with a black tie gala followed by an intimate performance from Rita Ora — guest starring Billy Porter.