The Business of Fashion

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

LONDON, United Kingdom — The most technologically advanced shoe in the world is an unassuming thing. It has a mesh upper, an inoffensive white sole and its proportions are vaguely sporty, but not overly so. It's like something a sensible relative would wear for a game of tennis. Yet step into the Nike HyperAdapt and a pressure sensor in the heel will detect your presence, a motor in the sole will begin whirring and a network of cables will tighten over the bridge of your foot. In short, it's a self-lacing shoe, and it's the first commercially available model of its kind.

Around the time of its UK launch, on a day in early autumn last year, I went to see a pair in action at an anonymous showroom in London. The shoes stood on a plinth and I watched as a technician activated them. A panel in the sole lit up and more lights began blinking across the heel guard as the shoe whirred and visibly contracted. It was an odd experience: like watching an impressive magic trick and a futuristic blood-pressure monitor at once.

When the shoe was first released in the US in 2016, it caused a frenzy, hitting a sweet spot between the already hype-prone worlds of trainers and tech. Wired magazine put it on the cover of its October issue, and many hailed the HyperAdapt as a technological breakthrough on a par with hover boards and floating cars. The space-age parallels made sense; anyone who has seen the 1989 sci-fi romp ‘Back to the Future Part II’ will recognise the HyperAdapt as a real-life version of the iconic Nike MAGs that magically fasten around Marty McFly’s feet.

Photo by Anuschka Blommers and Niels Schumm

ADVERTISEMENT

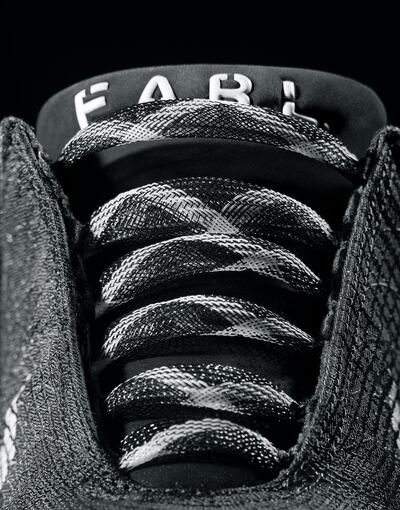

The fastening system, which goes by the retro-futuristic acronym E.A.R.L. (electro adaptive reactive lacing), was a combined effort of Nike’s vice president of creative concepts, Tinker Hatfield, who came up with the original idea for the Nike MAG, and a senior innovator, Tiffany Beers, who has since moved on to Tesla. The trainer first retailed at $720 and was distributed exclusively through an online lottery system. Despite the price tag, it sold out immediately and continues to do so with each re-release. At the time of writing there is a pair on eBay for £2,500.

Gimmicks

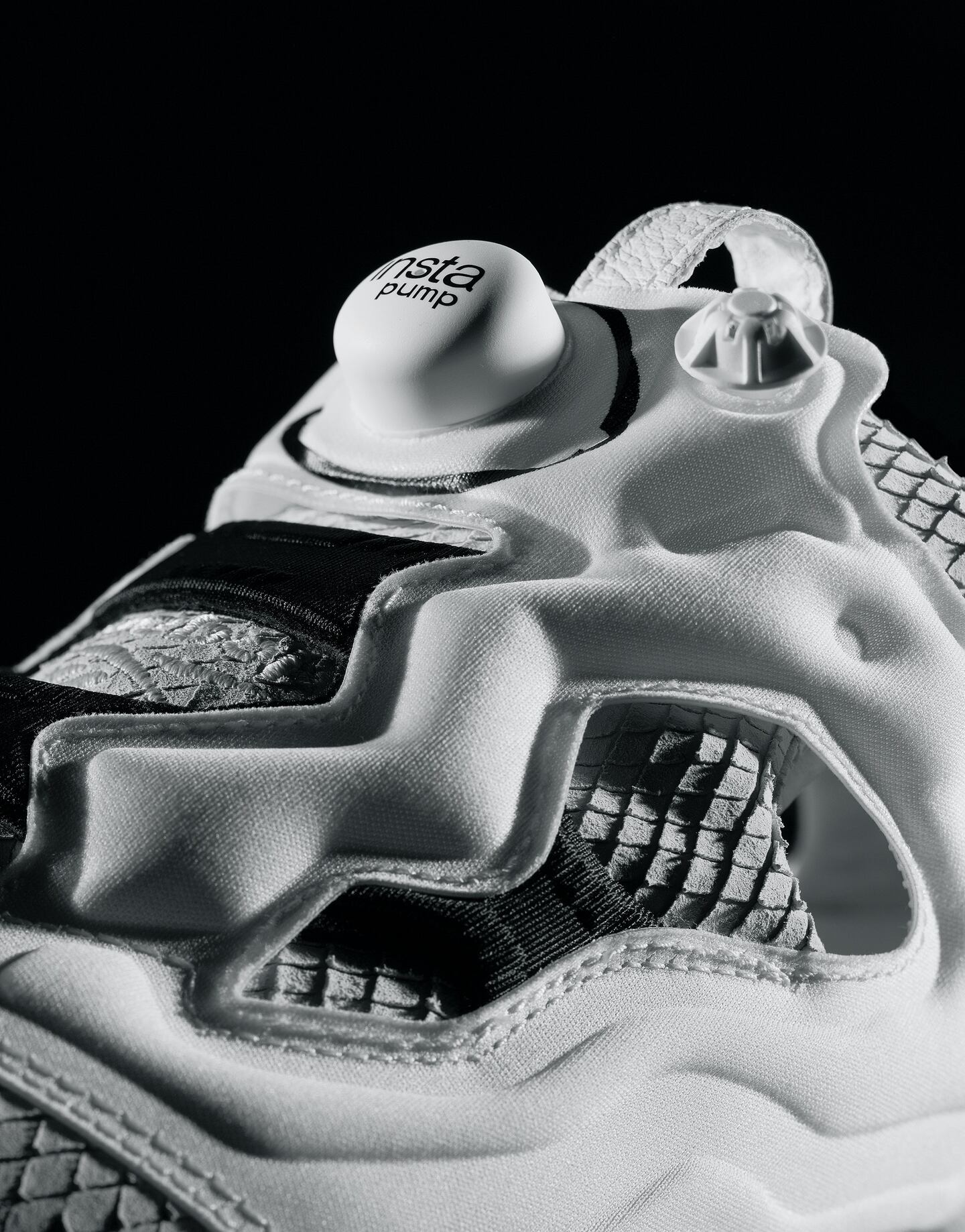

The pursuit of new and fabulous alternatives to laces has long been an obsession of the trainer industry. Ever since the Reebok Pump was released in 1989, selling more than $1 billion worth of units and opening up a new market for novel fastenings (at that time limited to slip-on Vans and Velcro), there has been a constant stream of new gimmicks. Some have been successful: the Puma Disc (a dial system that fastens a series of wires) and the Reebok InstaPump Fury (a fully laceless version of the Pump) have been in continuous production since the 1990s. Others, like the Nike Kukini (a laceless slip-on fastened by a web of translucent rubber) and the Adidas HUG (featuring a fold-out lever-and-pulley system), were more like failed visions of the future.

In the last few years, lace tinkering has reached unprecedented levels, and hardly a week goes by without a trainer being released with some sort of zip, toggle, wrap, strap, clip, magnet or cable network built into it. It's a symptom of an athletic-footwear industry in hyperdrive, which in the last three years has grown from $55 billion to an estimated $84.4 billion, even spawning its own secondary market of trainer reselling, which alone is worth more than $1 billion.

As the trainer market balloons, so does the arms race between sportswear companies. Soles get bouncier, insoles more supportive and uppers become lighter and more breathable. With its promise of a self-lacing future, the HyperAdapt is poised to turn lacing innovation into the most heated contest of all.

In 2008, while investigating the Areni-1 cave network in Vayots Dzor Province in south eastern Armenia, archaeologists from the country's National Academy of Sciences discovered a primitive laced shoe (a surprisingly modern-looking thing that Manolo Blahnik himself described as "astonishing"). It had been perfectly preserved thanks to the cool, dry climate inside the cave as well as the thick layer of sheep dung under which it had been buried.

Carbon dating identified the shoe as being from about 3,500BC, which makes it roughly 5,500 years old and the laces attached to it the oldest known examples of their kind – some 200 years older than those found on the shoes of Ötzi “the Iceman” in 1991. It also places laces (which are rarely well preserved) as at least as old as the earliest known wheel, making them some of the oldest, most consistently used pieces of technology in history and going some way to explaining their unique hold on our collective psyche.

Footwear will become more like a part of the body. Part of me versus something I put on.

Don't Fuss

"Laces are deep! Anything messing with them always feels groundbreaking," said Howie Kahn, a New York-based writer with whom I spoke on Skype. Kahn recently co-authored the book "Sneakers", an oral history of the trainer industry, with fellow journalist Alex French and designer Rodrigo Corral. "They're the main point of interaction with our shoes; they always have been," he added. "You don't fuss around with the toe cap before you put them on. You don't dig your fingernails into the sole."

When I spoke on the phone with Elizabeth Semmelhack, senior curator at the Bata Shoe Museum in Toronto and author of the book ‘Out of the Box: The Rise of Sneaker Culture’, she explained that laces have gone well beyond their initial purpose and now also occupy a ritualistic and symbolic role. “We may not often think about it,” she pointed out, “But along with learning to write, we still consider learning to tie shoelaces a fundamental milestone in a child’s development.”

ADVERTISEMENT

Why Do We Need Laces?

It makes perfect sense that Tiffany Beers, the creator of the first self-fastening shoe, now works for Tesla. If you can reinvent something as ancient and enduring as the lace, reinventing the wheel should be a doddle. "I wouldn't be at all shocked if there was some Nike – Tesla collaboration somewhere down the line," said Kahn, who interviewed Beers just before she made the move. Whatever she is doing there is clearly top secret, as all requests for an interview were immediately declined (although Tesla did offer me a ride in a new model of electric car.)

Aside from the symbolism of self-lacing shoes, and their obvious commercial appeal, their real importance lies in the possibilities they open up: once a brand figures out how to create a shoe that fastens itself, it’s not such a leap to imagine a system that can fasten reactively. “I think although we’ve reached the milestone of self-lacing shoes, the key battle over the coming years will be around adaptive lacing,” Kahn said. “It’s a humanity-changing proposition.” Feet change during exercise: they swell, they sweat. Shoes that are too tight or too loose can limit blood supply or cause blisters. A shoe that can handle lacing on the fly could adapt its fastening at the end of a race, or loosen it during periods of stoppage in play, giving the tiny advantages that, at an elite level, often make all the difference. This is not to mention the handiness of having laces that won’t come undone, and the clear benefits for those with disabilities.

Photo by Anuschka Blommers and Niels Schumm

Nike would appear miles in front, being the only major brand with a commercially available model of self-lacing shoe and therefore the only brand poised to move into adaptive footwear. But some in the industry believe the future of fastening is set to emerge from somewhere more unexpected. In November I met Daniel Bailey, a London-based independent footwear designer who has worked with such brands as Under Armour and Supreme and who also runs ConceptKicks, a popular website dedicated to innovative footwear. Over lunch he gesticulated with French fries as he outlined what is becoming a popular theory in footwear-design circles.

“Why do we need laces at all? Brands have been grappling with this challenge of how to reinvent shoelaces into yet another mechanical fastening, but they’re thinking about it all wrong,” he told me. “It seems so much more organic, inevitable even, that the future of fastening will come from a material breakthrough.” As Bailey described it, the world of material innovation is progressing at such a rate that he is convinced there will eventually be a way of making shoes from smart materials that completely do away with the need for laces — or any high-tech analogues.

Having a shoe that fastens through the very material it is made of would open up possibilities that go far beyond anything a mechanical fastening could offer: a shoe that could not only fasten around your foot, but respond to changes in temperature, or pressure, or hormones. Becoming warmer in the cold, stiffening on impact, or softening and expanding in the heat. It makes the thought of trying to invent a technologically advanced lace seem incredibly outmoded, like inventing the minidisc while MP3s loom on the horizon. If the interviews in "Sneakers" are anything to go by, it seems that Nike’s line of thinking may also shift to something more holistic, with Tiffany Beers hinting, “Footwear will become more like a part of the body. Part of me versus something I put on.”

Techy Stuff

Exactly what this new system will be is still theoretical. Bailey chucked around some ideas ranging from smart fabrics to magical goop. "You know, something that's a mixture of a natural, biological element and some kind of techy stuff," he offered. "They mix it together, wrap it round your foot and it just reacts. Bang! 'Hey shoe, I'm going for a run!' and it tightens up. I guarantee you some obscure company has made some mad stuff like that and we just don't know about it in the footwear world yet."

Indeed, many innovations in footwear occur through happenstance. When I called Steven Smith, the inventor of the Reebok InstaPump Fury, at work in Los Angeles, he told me that the shoe’s auto-inflation system came from a chance encounter at a mountain-bike trade show where he found a stall selling tiny automatic pumps for re-inflating inner tubes. Meanwhile the reinforced air bladders came from a company that designed life vests, and the carbon-fibre foot arch came from an aerospace firm that worked on SR-71 spy planes.

ADVERTISEMENT

Ultimately, laces are too aesthetically and culturally important ever to disappear.

For now, the most likely candidate appears to be knit, the shoe-manufacturing technology that in the past six or so years has revolutionised the way trainers are made. Instead of building a shoe by cutting patterns and sticking on more and more bits, the likes of Nike (with Flyknit) and Adidas (with Primeknit) are now able to knit one from scratch. The lightness, low production costs and environmental benefits have made knit indispensable. And the ability to knit a sock and stick it onto a sole triggered the unstoppable rise of the “sock-shoe” last year, with everyone from Balenciaga to Skechers having released a pair of eerily similar booties.

One of the people chiefly responsible for Primeknit is the industrial designer Alexander Taylor. He developed the technology with Adidas in the build-up to the 2012 Olympic Games, and in the grand tradition in footwear of borrowing from weird places, he got the inspiration from methods normally used for knitting chair upholstery. I visited his Farringdon studio in December and there he brought out boxes of early prototypes and knitted flat plans that looked like jock straps, but with a sleight of hand suddenly took the form of a running trainer. Like footwear origami!

Photo by Anuschka Blommers and Niels Schumm

A key moment in the development of Primeknit — and one that has the most potential to influence fastenings — Taylor explained to me, was when he discovered that adding special yarns to the knit allowed different parts of the shoe to function in different ways. By adding a thermoplastic “melt” yarn to the heel section, for example, it could be heated and hardened, removing the need to stick on a heel guard. Taylor invented a textile toolbox: each part of the shoe is knitted with a material primed to solve a different problem.

Already, models of Adidas UltraBoost are replacing laces with knitted bands of sturdier threads across the bridge of the foot to make them suitable for running. Extrapolating to the idea of adaptive shoes, Taylor said he found it easy to picture a shoe knitted with sections of smart yarn that can flex, expand or tighten when needed. Asked whether he knew if Adidas is specifically working on anything in that area, he politely told me he couldn’t comment. But throughout our meeting I noticed that his language had the tone not of if, but when.

Meanwhile, a fierce legal battle has been raging between Nike and Adidas since 2012 over who holds the patent for knitted footwear perhaps the biggest indication of the value that both groups place in the technology as a future for the industry.

It seems important to ask where the humble shoelace fits into the quest for smart-fastening super-shoes. Could we be facing a laceageddon? The designer Daniel Bailey told me that elite sports are certainly ruthless enough in their pursuit of medals, world records and trophies to leave laces behind should adaptive footwear deliver. “But I don’t think laces are going anywhere in wider society,” he added quickly. “Do you need cutting-edge self-lacing technology when you’re going to the shops? Not really. That’s what laces are for. Laces just work.” Ultimately, laces are too aesthetically and culturally important ever to disappear. For many, a trainer without a lace isn’t a trainer at all. “It would be like taking the smile off the Mona Lisa!” Howie Kahn wailed.

Sick

One evening last autumn, Kahn and French held a London launch for their book, "Sneakers", at a shop that specialises in re-selling rare trainers. There was a HyperAdapt, shrink-wrapped and perched on a shelf, which three teenagers were inspecting as I walked in. One of them lifted the shoe in his hand and commented on its surprising lightness. Then he put it back and the group joined the crowd that was forming around a vitrine in the middle of the shop floor. Inside were several pairs of the sold-out "ten" collaboration between fashion designer Virgil Abloh and Nike, a decidedly un-technological project where Abloh deconstructed ten classic trainers for the sportswear brand.

The kids squeezed themselves into the centre of the huddle until they were up against the glass and in sight of the coveted lace-ups. “You know these come with four sets of laces?” one said. “Sick,” replied his friend, leaning in close to observe the bits of string in shades of black, white, green and orange. For the briefest moment everyone fell silent. It was a primal, contented silence, the kind that often sets in when gazing at an open fire.

This article will appear in the Spring & Summer 2018 issue of Fantastic Man which will be released on 29 March 2018.

Related Articles:

Ugly 'Dad' Sneakers Luring Luxury

Nike Showcases Big Bet on Women's Sneaker Market

From analysis of the global fashion and beauty industries to career and personal advice, BoF’s founder and CEO, Imran Amed, will be answering your questions on Sunday, February 18, 2024 during London Fashion Week.

The State of Fashion 2024 breaks down the 10 themes that will define the industry in the year ahead.

Imran Amed reviews the most important fashion stories of the year and shares his predictions on what this means for the industry in 2024.

After three days of inspiring talks, guests closed out BoF’s gathering for big thinkers with a black tie gala followed by an intimate performance from Rita Ora — guest starring Billy Porter.