The Business of Fashion

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

Over the past several years, there’s been a flourishing movement of brands from Reformation to Marine Serre buying up deadstock fabrics unused by others and turning them into collections and sales of their own.

But for all the brands that want to get their hands on these materials, sourcing them remains a mostly analog process that’s time-consuming and difficult to do at scale. Brands often need direct relationships with other designers or mills to get information about their overstock. Or they can turn to jobbers who specialise in selling surplus fabrics and odd lots. Some resort to more hands-on methods.

“Basements,” said Collina Strada designer Hillary Taymour, explaining where she finds her deadstock. “It’s all in the know. A lot of people approach me now, which is nice because that’s a lot easier.”

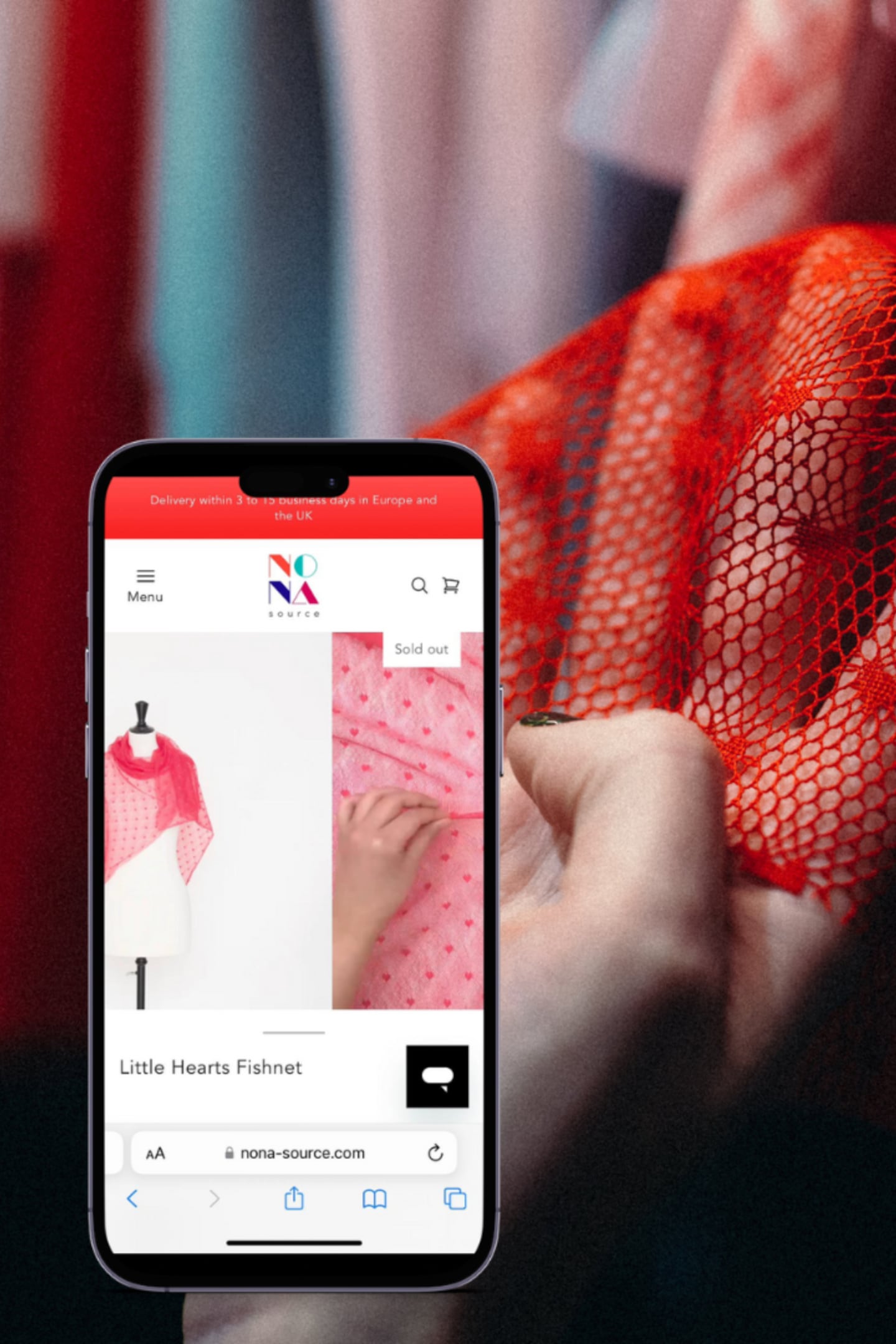

Digital platforms such as New York-based Queen of Raw and Nona Source, an in-house project from LVMH, are pitching technology as a solution. They offer e-commerce marketplaces and other capabilities to help sellers list fabrics online and buyers to find them, with the hope of making this trove of untouched materials accessible on an unprecedented level.

ADVERTISEMENT

For the brands that originally bought these fabrics, it provides a way to recoup some of their investment. They can get stuck with perfectly good fabrics because they purchased more than they needed, found the colour wasn’t quite right or changed course based on shifts in what shoppers were buying or internal design decisions.

And used or not, these materials have already added to the industry’s environmental problems. Upstream activities — notably producing and finishing raw materials — account for more than 70 percent of fashion’s greenhouse emissions, according to McKinsey.

A market made more efficient with technology could theoretically benefit all involved. But there are a number of challenges to overcome first.

Designers often want to touch and feel fabrics before they buy them, making them sceptical about shopping online, and it can be hard for larger brands to make use of deadstock because it’s typically available only in small quantities. For brands that want to sell or donate excess materials, they may not know how much they have or exactly where it’s located, and could be reluctant to do the work to catalogue and list it.

“We need to help companies understand this can be quick, it can be easy and it can be profitable,” said Stephanie Benedetto, co-founder and chief executive of Queen of Raw.

Benedetto, whose family has been in the garment industry for more than a century, established the company in 2018 as a fabric-resale marketplace, seeing the need for a better way for brands to offload their excess materials. But while brands liked the idea, they wanted an automated, easily scalable solution, she said.

Queen of Raw’s answer was to develop its own software, Materia MX, which through partnerships with software provider SAP and others plugs directly into a brand’s inventory-management system. Benedetto described it as a single platform for users to see what they have and where it’s sitting, whether it’s fabric or finished goods. It also lets them direct the inventory to be reused elsewhere in the company, resold on Queen of Raw’s marketplace, recycled or donated.

From what Queen of Raw has seen, brands are sitting on significantly more deadstock than they expected — about 15 times as much, according to Benedetto. Demand for the company’s services has been growing, she said, with inventory uploaded to its platform increasing 1,900 percent in the past year. One company using the software is Ralph Lauren, which noted in its 2023 sustainability report it diverted 11.8 metric tons (about 26,000 pounds) of unused materials from landfill using Queen of Raw’s global network of recyclers. It’s looking to expand the initiative.

ADVERTISEMENT

Buyers of the surplus materials on Queen of Raw’s platform can include emerging designers — the traditional deadstock customer, since they often need ways to buy less than the minimum yardage required at retail — but also large brands. In May, Shein announced its ambition to become a “leading rescuer of high-quality deadstock materials” through a partnership with Queen of Raw.

“We’re going to co-build some of these solutions together, and if it can work for us, we hope that every other brand is able to utilise some of these solutions and be able to do some of this at scale,” said Caitrin Watson, Shein’s director of sustainability.

The company said it aims to increase its use of deadstock significantly in the future. But Shein may be in a better position to rely on deadstock than most, because its entire model is based on creating small batches of products. Watson said they can use those 500 yards of fabric another brand has sitting around. Big brands don’t often function that way.

“For a large brand, a retailer, if you want this to be something that’s not just these one-off collections, you really are looking for a little bit more volume,” said Kathleen Talbot, chief sustainability officer and vice president of operations at Reformation. “We haven’t necessarily been able to scale it as a sourcing strategy along with our brand growth.”

When Talbot joined Reformation in 2014, the brand was still mostly using deadstock. Today, deadstock accounts for between 5 percent and 10 percent of Reformation’s materials.

While it’s perfect for small seasonal releases and novelty fabrications, like sparkly holiday styles, as the brand grew it had to shift to new fabrics for its increasingly large collections. Occasionally, they’ll come across a big batch of leftover material that works, like 20,000 yards of fabric the brand turned into suiting recently, but it’s hard to plan for. Still, earlier this year, the brand committed to increasing deadstock to 10 percent or more of its sourcing — and to sustain that — as part of a new circularity plan.

Quantity isn’t the only challenge. Reformation has a restricted substance list for chemicals found on textiles, and it can be difficult to get the chemical specifications of deadstock. It’s one reason it hasn’t yet jumped into sourcing through Queen of Raw or other technology platforms, according to Talbot, though they’re actively exploring the option and hope it can help them to increase their use of deadstock.

For now, its main sourcing method remains “boots on the ground” — sending designers to jobbers and warehouses, in part because the feel of a material is critical. It’s not alone in that view.

ADVERTISEMENT

“You need to touch it. You need to see how it drapes,” Collina Strada’s Taymour said. “It’s a more intense process than an add-to-cart situation, for me at least.”

Even so, Taymour recognises the potential of a technological solution for making deadstock more available. She said she’s trying to develop one with the Council of Fashion Designers of America, where she sits on the sustainability board.

Romain Brabo, having been a fabric buyer at LVMH-owned Givenchy in 2015, understands the need to communicate the touch and feel of fabrics as faithfully as possible. All the surplus fabrics he saw at the end of each season gave him the idea to create Nona Source, which LVMH launched in 2021 as a resale platform for materials from its houses. When one has leftover fabric, it alerts Nona Source, which collects it, inspects it and lists it on its platform. (Branded fabrics with house logos are recycled, not resold.)

The company has worked hard to translate the physicality of textiles digitally, including with videos, but many designers still aren’t ready to buy fabrics online, Brabo said. It’s why Nona Source established a physical showroom in La Caserne, the large fashion incubator in Paris.

“The textile industry is quite what we call an ‘old lady,’” he noted. “It’s a very big move for the industry to switch to a digital model.”

But the company is gaining traction, with brands including Gabriela Hearst, Cecilie Bahnsen and a number of small labels now using Nona Source to buy luxury-quality deadstock.

Both Nona Source and Queen of Raw use the low-tech option of sending swatches or sample yardage, too. But they’re exploring new avenues as well. Nona Source is working on 3D tools that would let you see in more detail how a fabric drapes and moves. Queen of Raw is investigating 3D and technologies like augmented and virtual reality.

They may not get every brand to rely on deadstock rather than new fabrics, but both companies feel they can still have a meaningful impact on how brands handle their surplus and how others buy it.

And both said they believe they can do so at a scale that wouldn’t be possible without technology.

LVMH is part of a group of investors who, together, hold a minority interest in The Business of Fashion. All investors have signed shareholders’ documentation guaranteeing BoF’s complete editorial independence.

This season more than 30 brands on the New York Fashion Week calendar have a focus on sustainability.

From The RealReal dropping upcycled collections to LVMH planning to launch a platform to sell off deadstock fabrics, fashion is finding value in its excess.

As the fashion industry grapples with how to keep old clothes out of landfills, finding ways to scale long-standing upcycling initiatives offers one near-term solution.

Marc Bain is Technology Correspondent at The Business of Fashion. He is based in New York and drives BoF’s coverage of technology and innovation, from start-ups to Big Tech.

The algorithms TikTok relies on for its operations are deemed core to ByteDance overall operations, which would make a sale of the app with algorithms highly unlikely.

The app, owned by TikTok parent company ByteDance, has been promising to help emerging US labels get started selling in China at the same time that TikTok stares down a ban by the US for its ties to China.

Zero10 offers digital solutions through AR mirrors, leveraged in-store and in window displays, to brands like Tommy Hilfiger and Coach. Co-founder and CEO George Yashin discusses the latest advancements in AR and how fashion companies can leverage the technology to boost consumer experiences via retail touchpoints and brand experiences.

Four years ago, when the Trump administration threatened to ban TikTok in the US, its Chinese parent company ByteDance Ltd. worked out a preliminary deal to sell the short video app’s business. Not this time.