The Business of Fashion

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

Just a year ago, luxury dotcom valuations were flying high. Farfetch was trading on a forward sales multiple approaching 12.8x (a 266 percent premium to dotcom benchmark Amazon); venture capital money was flooding into the sector; and the demand for luxury dotcom IPOs remained unsatiated, as evidenced by the initial stock market performance of MyTheresa and The RealReal. But towards the end of 2021, the luxury dotcom pink cloud turned into a hail storm and now the sector’s key constituents are trading on average at a 50 percent discount to Amazon. What drove the boom and how to make sense of the current bust?

The luxury sector has been a laggard in e-commerce investments in the belief that selling the dream required physical shopping environments, such as flagships and department stores. Furthermore, the sector is highly exposed to travel retail and tourism. In 2020, the Covid pandemic forced a radical pivot to digital, which meant that “digital-first” luxury businesses thrived disproportionately. Farfetch’s revenue increased by 64 percent that year, whilst MyTheresa’s sales grew by 47 percent. Farfetch continued its exponential growth in 2021 ending the year with turnover more than double pre-pandemic levels.

This upturn in prospects was fully capitalised upon by luxury dotcom players. In November 2020, Farfetch secured a $1.15 billion funding package from Richemont and Alibaba as part of a deal to develop Farfetch China. Vestiaire Collective completed three funding rounds during the pandemic, raising a total of $488 million with the latest round valuing the business at $1.7 billion, while Ssense raised an undisclosed sum from Sequoia Capital China at a $4.1 billion valuation. MyTheresa, The RealReal and Rent the Runway all raised capital through IPOs during the pandemic period.

According to Venture Scanner, a research firm that tracks investment activity across industries: “Funding into retail-tech start-ups through June 2021 has already surpassed the total 2020 amount, and exits are also quite hot. After getting used to being stuck at home, retailers and consumers adjusted to take advantage of the digital environment, and investment money is flowing to power this transformation.” That was the scene in early 2021.

ADVERTISEMENT

Of course, rapid growth is the crack cocaine of investors. So much so that there are often epic consequences when it slows. Some of us are old enough to remember the fantastic bull run enjoyed by Capri Holdings (then Michael Kors) fuelled by high double-digit sales growth as the brand expanded its retail reach throughout the world. At its valuation peak, the stock was trading on a forward EV/EBITDA multiple of 28.2x, a 49 percent premium to Hermès’ valuation on the same day and almost double the SLI average in that period. Eventually, the Michael Kors brand ran out of steam, with a catastrophic impact on valuation.

The outlook is potentially worse for luxury e-commerce valuations given the preponderance of loss-making companies in the sector. That’s probably why the correction has thus far been so swift and so severe. With the exception of The RealReal, luxury dotcom stocks peaked in 2021. Farfetch, MyTheresa and Rent the Runway all hit rock bottom in terms of EV/Forward Sales multiples this May, around a year after their peak. Now, leading luxury dotcom stocks trade at a significant discount to Amazon.

This boom-and-bust cycle does not reflect the underlying fundamentals of luxury goods, which tend to be relatively recession-proof. The answer may well be found in the scarcity of investment opportunities in luxury. The sector has traditionally been family-owned; even some of its largest listed companies are controlled by their founding families. The advent of Covid lockdowns further narrowed the scope of investment opportunities in luxury as so many companies were far behind the digital curve, and thus heavily reliant on brick-and-mortar retail. Luxury e-commerce thus offered a temporary safe haven for luxury investors. Now that shops are back open, brick-and-mortar retail is coming back in some cases stronger than before, investors have a choice to make between fast-growing but loss-making and cash consuming dotcom companies or fast recovering, highly profitable and cash generative traditional luxury goods players.

Corporate activity is normally a go-to solution for companies in the search of a valuation upgrade. That was certainly the agenda that drove the transformation of Michael Kors into Capri Holdings via the acquisitions of Jimmy Choo and Versace. Farfetch has made quite a few investments outside of its core e-commerce business model. The platform acquired the legendary London boutique Browns in 2015 and Milanese brand accelerator New Guards Group (which operates Off-White) in 2019. In April, it announced a $200 million minority investment in Neiman Marcus Group, which is notable given that Neiman Marcus filed for bankruptcy at the start of the pandemic, illustrating just how quickly fortunes can change.

Expansion of product offering is another tool used by companies to apply for an investor upgrade. Luxury brands have been riding the gravy train of product diversification for many decades, with notable success in leather goods and beauty. Farfetch has been busy in this area, too, most notably announcing the launch of Farfetch Beauty this April. The company has also made bolt on acquisitions in e-commerce, namely beauty e-tailer Violet Grey in February and online sneaker marketplace Stadium Goods in 2019.

But both of the strategies outlined above typically have more of an impact in the long term as investors will always factor in execution risk in the short term, as evidenced by the paltry market response to Farfetch’s investment in Neiman Marcus.

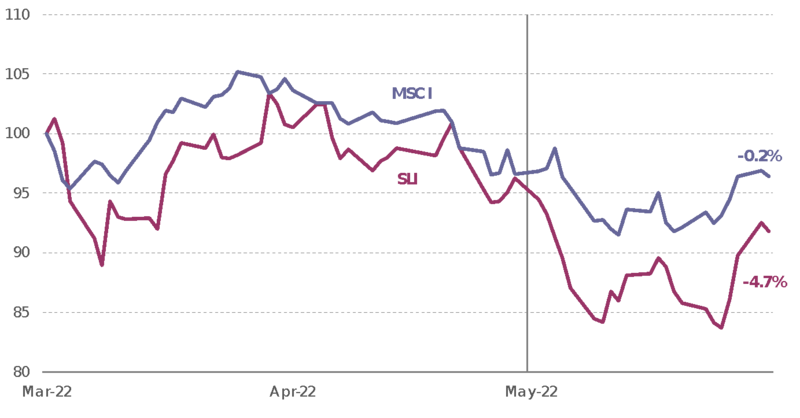

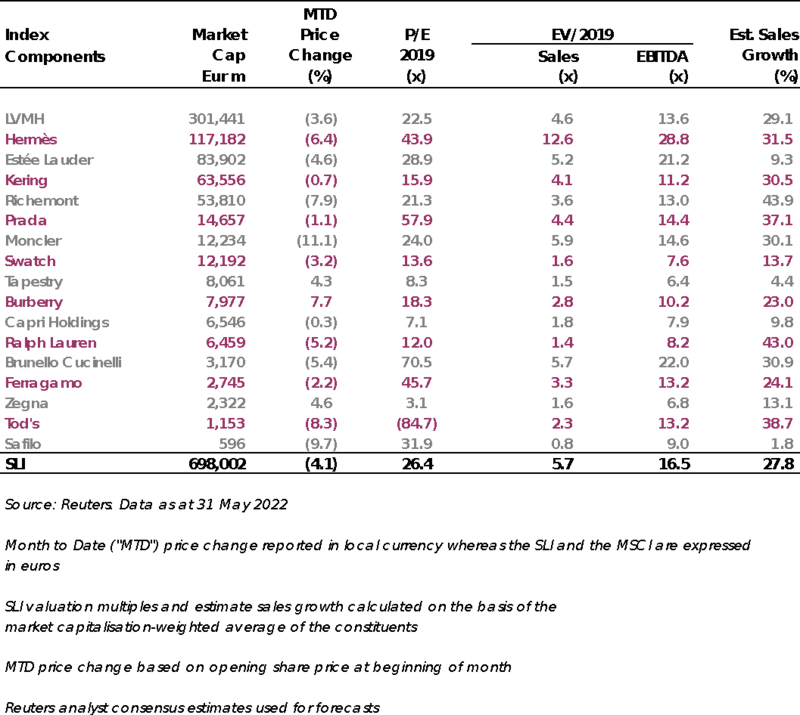

The Savigny Luxury Index (“SLI”) fell 5 percent in May driven by further negative economic and geopolitical news, notably including the biggest interest rate hike in the United States since 2000 and investor nervousness in the run-up to Russia’s Victory Day on 9 May. The MSCI’s performance was flat this month.

The world’s 50 top richest people have lost more than half a trillion dollars on paper this year, a gargantuan loss that exceeds the gross domestic product of Sweden. Worst hit has been technology entrepreneurs such as Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos, Bill Gates and Mark Zuckerberg. The stock market slide also reversed the gains the world’s wealthiest people saw during the start of the pandemic when a billionaire was created every 30 hours. The months-long sell-off that has been hitting technology stocks particularly hard has spread beyond technology. Luxury magnate Bernard Arnault has lost 30 percent of his wealth since the beginning of the year. How much to go before luxury stocks are attractive again?

Pierre Mallevays is a partner and co-head of merchant banking at Stanhope Capital Group.

During a blockbuster year for online sales, Farfetch surged ahead of rivals to position itself at the front of luxury’s e-commerce race. Can it spin the current momentum into sustainable — and profitable — growth and become the unrivalled platform for luxury fashion online?

How has Mytheresa made online luxury profitable when competitors have struggled? CEO and President Michael Kliger reveals the secrets to the company’s success.

In 2020, like many companies, the $50 billion yoga apparel brand created a new department to improve internal diversity and inclusion, and to create a more equitable playing field for minorities. In interviews with BoF, 14 current and former employees said things only got worse.

For fashion’s private market investors, deal-making may provide less-than-ideal returns and raise questions about the long-term value creation opportunities across parts of the fashion industry, reports The State of Fashion 2024.

A blockbuster public listing should clear the way for other brands to try their luck. That, plus LVMH results and what else to watch for in the coming week.

L Catterton, the private-equity firm with close ties to LVMH and Bernard Arnault that’s preparing to take Birkenstock public, has become an investment giant in the consumer-goods space, with stakes in companies selling everything from fashion to pet food to tacos.