The Business of Fashion

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

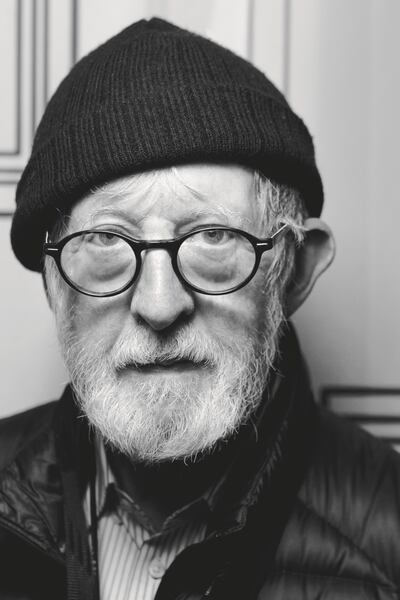

PARIS, France — The photographers' pit at the end of a catwalk is no place for the faint-hearted. Before shows start, the predominantly male phalanx can be heard shouting, "Uncross your legs!" and if a model retreats too early, before she reaches the optimal mark on the runway for being photographed, a collective growl often cuts through the soundtrack. The lensmen are largely unfashionable — something of an antidote to the hyper-ostentation of fashion's street style peacocks — and travel with their heavy-looking cameras and equipment in tow from show to show. Amongst them is a silver-haired sparrow-like man. His name is Chris Moore and he's perhaps the first and oldest catwalk photographer working today, whose pictures end up everywhere from The New York Times to Vogue.

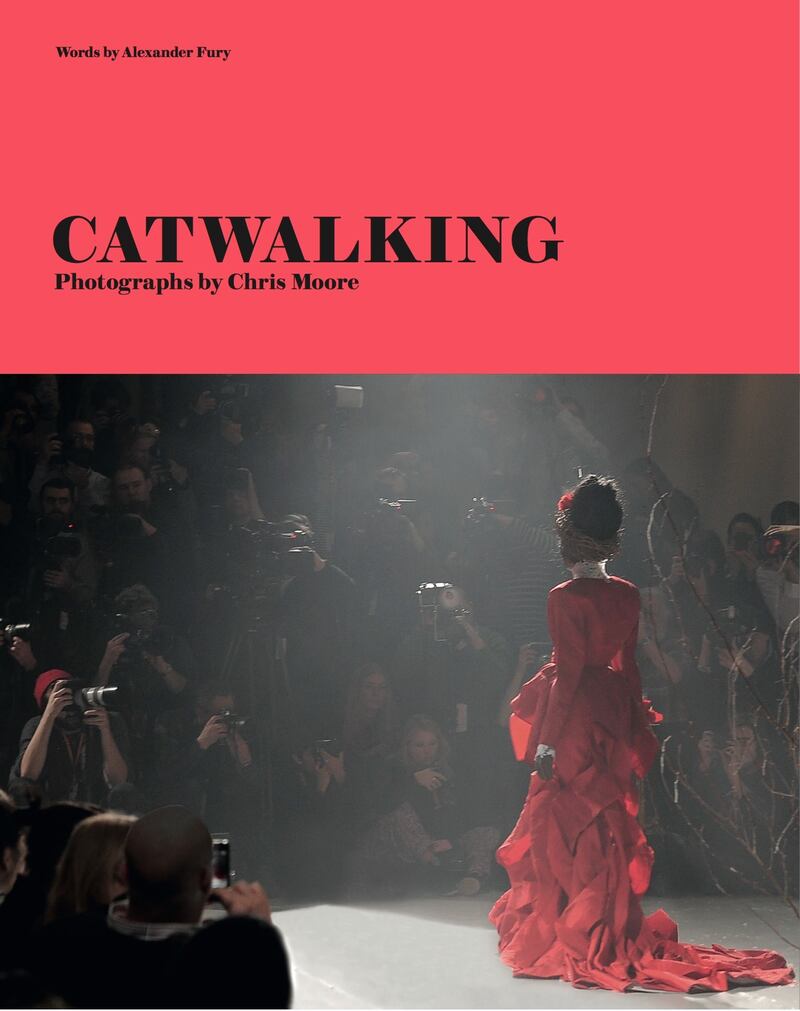

Moore — an octogenarian who was awarded a special recognition honour at the British Fashion Awards, a lifetime achievement award at Graduate Fashion Week and who still works today — has been nicknamed "the bishop" by his peers, perhaps for his calm posterity and rank amongst them. He is unassuming, often taking public transport between the shows, with a humble gait and round glasses. After a recent day at the Paris shows, not without its challenges — Moore likens the smoky ambience at Balenciaga to photographing fog — the 83-year-old photographer returns to his hotel to edit and upload his images. A couple of hours later, we meet in the hotel bar over the heavy tome "Catwalking: Photographs by Chris Moore", authored by Moore in collaboration with writer Alexander Fury.

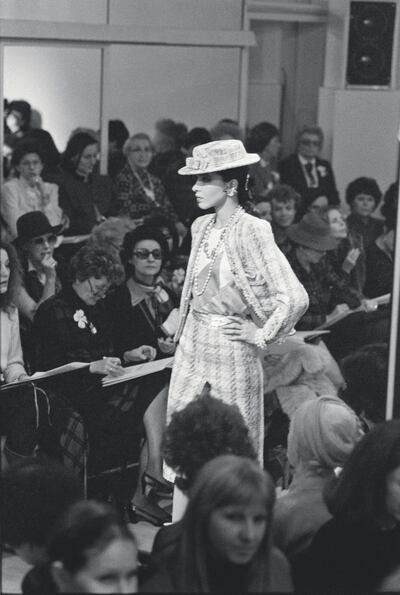

The book traces Moore’s career, from 1954 to 2017, and contains rare black and white images of fashion shows from a time when photographers were largely prohibited, all the way up to today’s saturated catwalk imagery, digitally captured in colour for his online photo agency, Catwalking.com.

Catwalk photographer Chris Moore | Source: Courtesy

ADVERTISEMENT

Moore grew up in Northumberland and took a keen interest in photography from an early age. His first camera was a 35mm Agfa Karat, which he took with him, when, aged 16, he moved to London without any formal training to begin work as an apprentice at Gee & Watson, a block-making studio in the heart of Fleet Street (block-making was a way to mass-produce imagery for publication). After a couple of years, he was recommended for an assistant job at Vogue Studios, where the magazine’s pashas of fashion photography — Cecil Beaton, Norman Parkinson, Clifford Coffin and Henry Clarke —would photograph the great beauties of the day.

For a working-class boy, it must have been an exotic and enticing world. “I had no idea about Vogue [because] it meant nothing to me,” he reflects. “It was just photography I was interested in.” However, for Moore, who left school at 15, it was valuable training. “I suppose being at the Vogue studios was like being at an art college in a way; it was very life-fulfilling,” he concurs.

His first time abroad was assisting Henry Clarke — a pioneer of the exotic “on location” fashion shoot — in Sicily with Elsa Martinelli and Fiona Campbell-Walter, the future Baroness of Thyssen. “It was a magical trip,” recalls Moore. “I learnt a lot. I remember clutching my passport as I walked down the steps of the airplane and thinking I didn’t know what to do, I was approached by someone who asked if I wanted a taxi and I said, ‘Oh yes please!’ and I discovered I was in a horse-drawn carriage in Palermo!” It was on that trip that he first drank wine with a meal and tasted the allure of continental Europe.

Moore initially harboured dreams of becoming one of the bright new fashion photographers of the day, like his working-class counterparts David Bailey, Terrence O'Donovan and Brian Duffy. However, he was firmly in an assistant's role and had to leave Vogue because it wasn't paying well enough. He went to a photo agency, where he was successful but reluctant to take a two-year contract, and has worked freelance ever since. Jackie Moore, his first wife, was a fashion journalist who encouraged him to go to the haute couture shows in Paris (Milan, London and New York fashion weeks were non-existent at the time; just as ready-to-wear in Paris was yet to be born). The Chambre Syndicale de la Haute Couture's rules, however, were very strict, in order to prevent the copying of the clothing on the runway.

"I like the fact that everyone is a photographer, especially as the French were terribly against it, trying to stop the power of the people."

“You weren’t ever allowed to photograph a show [because] there was always this embargo,” explains Moore. Instead, a small number of photographers would be invited to the houses after the show to shot clothes that were specifically intended to be shown to the press. “One would use the house models and one would need to pay them the equivalent of four francs per garment that you photographed. So that’s what went on, and then suddenly, ready-to-wear started and they let photographers in.”

Rather than showing fashion months after its original presentation in a conceptual editorial setting, Moore's work showed fashion at the source. By the mid-1960s, Moore was a regular at the Paris shows and although certain houses such as Balenciaga, Givenchy, Chanel and Christian Dior continued to close their doors to photographers, others began to challenge the century-old strictures of the Chambre Syndicale. He was there to capture the space-age designs of Courrèges and Cardin, which were eventually followed by the ascent of ready-to-wear from Yves Saint Laurent, Chloé and Kenzo. By the end of the decade, even Coco Chanel had opened her salons in 1970 for what would be her final collection. For the first time, she invited press photographers inside to record the clothes. Among them was Moore.

Chris Moore's catwalk photograph | Source: Courtesy

“Chris Moore’s career would fuse two key elements of his early years and training: Fleet Street and fashion; the immediacy of newsprint journalism fused with the considered eye of a Vogue fashion photographer,” writes Alexander Fury in the book, which will be published next month by Laurence King. “Generations of fanatics have experienced and continue to experience fashion through [his eyes]… Chris Moore was present for the true birth of the modern notion of the ‘catwalk’, and our contemporary idea of the fashion show.”

ADVERTISEMENT

Over the years, Moore has evolved from shooting in black and white film and developing photos in his hotel bathroom to shooting in colour with high-tech cameras and working online. "I can remember with Suzy Menkes, suddenly The Daily Telegraph was scooping her and she felt they were getting stuff out and the [International Herald Tribune] was lagging behind," explains Moore of the turning point in the early 1990s. "She spurred us on to doing things quicker, and she really did get us onto digital very early because of the deadlines." His first digital camera was borrowed from the Evening Standard, where it had previously been used to photograph athletic events at the Olympics. "At the beginning, they weren't auto-focus, which was very difficult and you had to really concentrate because you pre-focused so the model walked into the picture, as it were. Then they bought out autofocus lenses and the whole thing changed."

“After all those millions of images Chris took for me, I can remember only once or twice seeing a blurry one,” says Suzy Menkes, who worked with Moore whilst she was fashion editor of International Herald Tribune. “After a show in Paris, we would run together with the negatives to the printer. It was always a question whether the photo guy would have drunk too much at lunch to get on with the development. I would then leap on the metro to the IHT office to make sure the picture would be printed before the 7:00pm deadline.” As for Moore’s sensibility, Menkes describes him as “old school.” “[He uses] the ‘70s way, saying: 'This way — to the left!’; ‘That's marvellous!'; ‘Another smile!'”

I enjoy the people, I enjoy the spectacle, and the challenge.

In 1999, he launched his own online photo agency, Catwalking.com, which provided the great and good of fashion publications and newspapers with imagery direct from the shows. Since 2008, it has worked in tandem with Getty, where Moore’s images can be bought, and has survived the threat from street-style imagery as it approaches its second decade (publications have shifted their budgets from catwalk imagery — which can often be provided by fashion houses for free — towards street style imagery). Catwalking chimed with the 2000 launch of Style.com, which published reviews and galleries of designers’ collections, and the subsequent movement towards a wider public fascination with the complete collections of designers, often experienced in a grid of imagery. The two websites have respectively changed the way designers see themselves, often considering the look of a collection in a two-dimensional format, which will be seen on a website and on social media by its potential consumer. It also liberated designers from the subjective edit of their shows by the press: instead of highlights, the collection can be shown in its entirety.

Today, fashion shows are awash with members of the audience photographing or livestreaming the looks for social media. It could be a threat to traditional fashion show imagery, but instead, it fuels demand for high-resolution versions. “I like the fact that everyone is a photographer,” says Moore. “I think it’s absolutely great, especially as the French were terribly against it, trying to stop the power of the people.”

'Chris Moore: Catwalking' book cover (Thom Browne A/W'13) | Source: Courtesy

Moore's favourite shows to photograph were Alexander McQueen, John Galliano and Hussein Chalayan in the '90s and early '00s. The element of spectacle and narrative-driven sets made for interesting pictures. "There is a problem at the moment, certainly this season, where girls are beginning to look as if we're doing a catalogue all the time, you know?" He cites Gucci as an interesting one to photograph now. "The lights were flickering all the time — I liked that," he says, before mentioning that he prefers a challenge to a homogenous line-up.

Today, the cramped photographers’ pit at the end of a catwalk can hold as many as 50 lensmen. On some occasions though, it might be just five. At Alexander McQueen’s first posthumous Autumn/Winter 2011 salon show — the “Hieronymus Bosch” collection finished by McQueen’s team — Moore was the only photographer to be let in. Indeed, McQueen would warn Moore in advance of his shows so that he could capture them correctly. When the designer finished his Spring/Summer 2001 show with a collapsing tank of moths and writer Michelle Olley in a gas mask, Moore was able to photograph it with a special camera designed for capturing the motion in a burst of photos and, as a result, became a part of McQueen’s process, immortalising his performative show.

However, despite his reputation, Moore can still be turned away in the scrums to get into shows. “I did get rejected this week from Chloé. Bastards! I don’t know why, but I did.” The irony is that many designers will send the catwalk imagery to Moore if he is not able to attend the show in the hopes that it will still be distributed by Catwalking.com.

ADVERTISEMENT

Moore regularly threatens to retire, but shows no sign of slowing down. “This job steals the summer, steals the spring and steals the autumn and I want some of that back,” he says one minute, but one gets the impression that he may find it hard to give it all up. “I enjoy the people, I enjoy the spectacle, and the challenge,” he adds. There’s also the physical demands of the job, but he insists he is healthier because of it. “I think the shows have kept me young and fit,” he reasons. “I can’t say I feel too fit at the moment,” — it is the end of the seventh day of Paris Fashion Week, after all — “but the physical thing of shooting shows, you have to learn to keep calm. There’s a lot of things you learn, doing a job like this.”

Related Articles:

[ Inside Tim Blanks' Box of '90s PolaroidsOpens in new window ]

[ Alexandre de Betak, Fashion's Wizard ProducerOpens in new window ]

From where aspirational customers are spending to Kering’s challenges and Richemont’s fashion revival, BoF’s editor-in-chief shares key takeaways from conversations with industry insiders in London, Milan and Paris.

BoF editor-at-large Tim Blanks and Imran Amed, BoF founder and editor-in-chief, look back at the key moments of fashion month, from Seán McGirr’s debut at Alexander McQueen to Chemena Kamali’s first collection for Chloé.

Anthony Vaccarello staged a surprise show to launch a collection of gorgeously languid men’s tailoring, writes Tim Blanks.

BoF’s editors pick the best shows of the Autumn/Winter 2024 season.