The Business of Fashion

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

“Why is Issey Miyake so often singled out as a fashion designer whose work somehow lies above or beyond fashion?” That was the question posed by The New York Times in December 1998. And Miyake himself would have been the first to resist such an elevated proposition. He rejected any suggestion that what he did was art, although it was often so breathtakingly transcendent that it was hard to think of it in any other terms. Instead, in interviews and in the many books and exhibitions devoted to his work, Miyake would insist he was “making things.”

From the moment he launched Miyake Design Studio in 1970, everything started for him with “A Piece of Cloth” (A-POC would much later become the label he gave one of his most futuristic offshoots.) Under the umbrella of such a humble notion, Miyake, who passed away in Tokyo last week at the age of 84, established himself as fashion’s greatest humanist. His clothes were a multifaceted celebration of life: movement, energy, experience and an infectious joy that was rare in fashion. And which applied to Miyake the man, as much as to Miyake the designer.

It’s not so hard to imagine that his love of life stemmed from an unimaginably traumatic childhood experience. Born in Hiroshima, Miyake was seven when he and his sister watched from the hills above the city as it was destroyed by an atomic bomb on August 6, 1945. His mother was badly burned, and died four years later. That terrible moment, literally fusing past, present and future, birthed an uncertain new world, and a new global consciousness. In Miyake, it nurtured a strong emotional investment in Japan’s recovery.

He chose fashion as his vehicle because, as he once told me, “Clothes are not abstract like architecture or graphic design, they’re a public reflection of people’s joys and hopes.” Fashion also represented a kind of personal liberation for Miyake. “I wasn’t following in anyone’s footsteps, so I was free,” he said in that same conversation.

ADVERTISEMENT

Miyake became an enthusiastic citizen of the new world. After graduating in 1964 from Tama Art University in Tokyo, he moved to Paris to study at the École de la Chambre Syndicale de la Couture Parisienne, which prepared him for jobs, first with Guy Laroche and then, in 1968, with grand couturier Hubert de Givenchy. But the May ‘68 protests in Paris accelerated a societal shift. And it was blue jeans, not couture dresses, New York rather than Paris, that captured Miyake’s imagination. So he moved again. He spent six months working for Geoffrey Beene on Seventh Avenue before heading back to Tokyo in 1970, head swimming with radical visions, determined to find something in Japanese fashion culture that broadcast a break with traditions of formal dress as clearly as a pair of jeans did in the Western world.

He found it in sashiko, the cotton quilting technique used for centuries on workers’ hardwearing clothing. It became an instant signature. Miyake also developed body suits, possibly inspired by the designs of the ultimate American modernist Rudi Gernreich. “I’m not sure he was that,” Miyake would later write in Rudi’s obituary. “I can only say that he was a designer who was always thinking of new ways to express ideas about the human body using clothing.” Curiously, both designers had originally set out to be dancers. They shared in their work an obsession with bodies in movement. Miyake found his ideal fabric, polyester jersey, to express exactly that, for all sizes, all ages. So in that one year, 1970, his Design Studio managed to marry past and future to create a new fashion language.

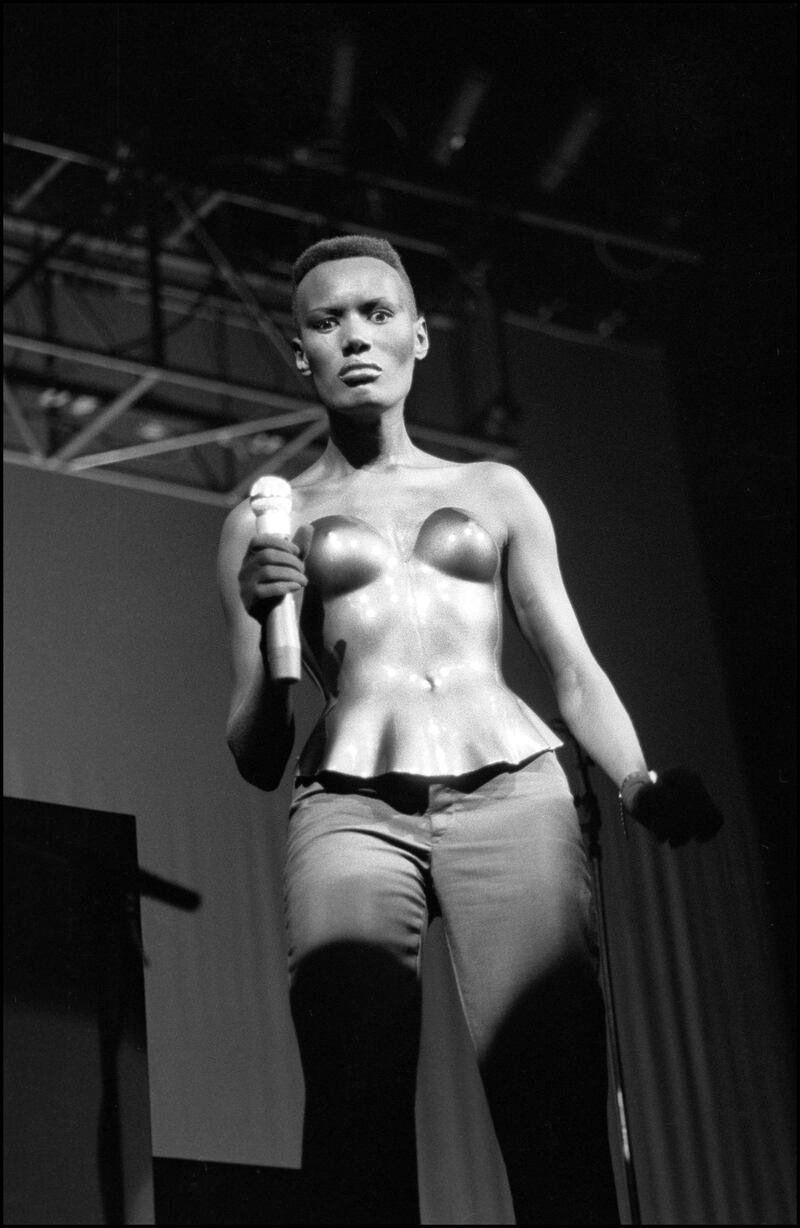

Though Miyake’s designs continued to draw on the fluidity, the volume, the body-wrapping of indigenous Japanese garb, he never liked the label of “Japanese designer.” From 1973 onwards, he presented his collections in Paris, and occasionally in New York. Among the like-minded post-Hiroshima generation he worked with were graphic designer Tadanori Yokoo, whose style was equal parts Hokusai and Haight Ashbury, architect Tadao Ando, store designer Shiro Kuramata and art director Eiko Ishioka. “Issey Miyake and Twelve Black Girls,” Eiko and Issey’s 1976 collaboration at the Shibuya Parco shopping centre, was a brilliant up-yours to lockstep Japanese conformity. (Grace Jones, who modelled in the show, would go on to create one of Miyake’s most indelible images in the moulded plastic body he made for Autumn/Winter 1980.)

“Design is teamwork,” he would say, and his naturally generous spirit produced not only fashion spectacles with Eiko, but also the revolutionary perfume and packaging of L’Eau d’Issey (designed with Fabien Baron in 1992), a particularly fruitful collaboration with photographer Irving Penn, and a lengthy relationship with the Frankfurt Ballet under choreographer William Forsythe, starting with “The Loss of Small Detail” in 1991. It was while working on this production that Miyake began to fully explore the way pleats moved and changed with the dancers’ bodies, “like a kaleidoscope,” he said. Out of these experiments came one of his greatest triumphs, the “Pleats, Please” collection, launched in 1993.

Twenty years later, Miyake finally got round to launching a male equivalent, Homme Plissé, which has proved to be another success for his brand. But by then, Miyake was no longer involved with the actual design of the clothes that bore his name. Instead, he devoted his last decades to research, always looking for new techniques which were fed with great effect into the collections designed by a succession of talented acolytes. And they’re usually presented with the combination of joy and jaw-drop that is vintage Miyake.

His own fusion of tradition — starting way back when with sashiko — and technology has created a potent legacy, which echoes now in the work of young designers like Craig Green, Jonathan Anderson and Samuel Ross, as well as Naoki Takizawa, Dai Fujiwara and the other graduates of the Miyake Design Studio.

And that question posed by The New York Times in 1998 has been answered by a succession of exhibitions all over the world. Miyake insisted on “making things” but he would go on to define those things as “clothes for living.” See them grouped in shows and their colour and verve and form slam you with a reminder that there is nothing more worthy of celebration than life, which truly lies “above or beyond” fashion.

The former CFDA president sat down with BoF founder and editor-in-chief Imran Amed to discuss his remarkable life and career and how big business has changed the fashion industry.

Luxury brands need a broader pricing architecture that delivers meaningful value for all customers, writes Imran Amed.

Brands from Valentino to Prada and start-ups like Pulco Studios are vying to cash in on the racket sport’s aspirational aesthetic and affluent fanbase.

The fashion giant has been working with advisers to study possibilities for the Marc Jacobs brand after being approached by suitors.