The Business of Fashion

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

NEW YORK, United States — It was dusk at Pier 26 in Manhattan when the monk began to chant, a deep, rolling vibrato you could feel in the pit of your belly. Across the flat, open expanse of the pier, which juts out into the Hudson River, a friar in a long tunic stood atop an open-air staircase, holding a pair of birch saplings. He gazed toward a fully clothed woman beneath a running shower on the roof of a tin shanty and, beyond her, a pair of identically dressed bearded men, one clutching the other in his arms like a teddy bear.

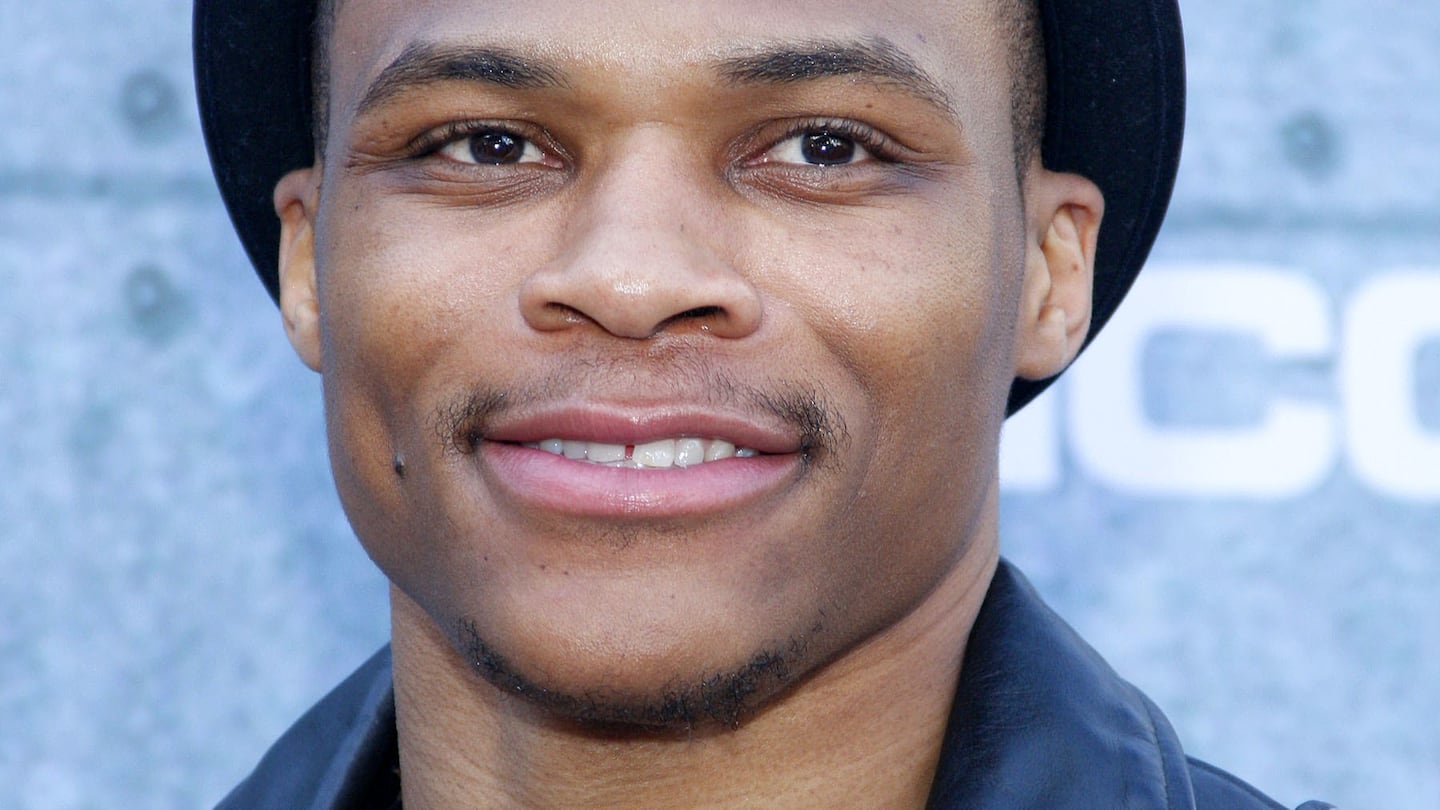

For the uninitiated, the experience was like waking up in a surrealist painting or discovering you'd ingested a lot of peyote. For Russell Westbrook, All-Star point guard for the Oklahoma City Thunder, it was just another fashion show, albeit the most hotly anticipated of this fall's New York Fashion Week: Givenchy was unveiling its 2016 spring line. Westbrook, 26, wearing a look of rapt interest, had planted himself at the runway's edge alongside Kim Kardashian, Kanye West, and Vogue's Anna Wintour. Afterward, he hustled backstage to pay his respects to the French label's creative director, Riccardo Tisci. "Every time I walk into a fashion show, I get excited," he says.

If you know one thing about Westbrook, it’s probably his hyperaggressive, shoot-first, baseline-to-baseline style of play. For a few months this spring, en route to winning the NBA scoring title, he was so phenomenally good, racking up triple- doubles almost every night, that he took over the opening block of ESPN’s SportsCenter in the same way Donald Trump takes over a GOP presidential debate. You tuned in to witness the sheer majesty of the performance.

If you know two things about Westbrook, the second is probably the glasses. During the 2012 NBA Finals, when the Thunder took on the Miami Heat, he showed up at a news conference in a colorful Prada shirt and lensless red specs — “nerd glasses,” the press dubbed them — that had a sudden, seismic effect on the sports world and brought together Westbrook’s two great passions: basketball and fashion.

ADVERTISEMENT

Basketball and fashion. These two worlds intersected only occasionally before 2012. Stylewise, pro sports was a wasteland. Turn on ESPN even today, and you’re confronted by a ghastly array of baggy four-button suits, Chris Berman wearing neckties seemingly on a dare, and Merril Hoge in starched collars, with tie knots as big as satin throw pillows. The jock code frowned on fashion. So when Westbrook wore his famous glasses, the jocks reacted as jocks do — with mockery. The next day, Charles Barkley and the crew of TNT’s Inside the NBA donned red glasses to tweak Westbrook’s unique style. (Barkley, who’s as smooth and round as a 400-pound Milk Dud, typically shrouds himself in suits that resemble gabardine muumuus.)

But here’s what happened next — a ton of NBA players, and plenty of other people, too, started wearing lensless frames. The Prada shirt sold out. Westbrook watched with amusement. “I started wearing frames back in middle school,” he says, a few days after the Givenchy show. “I used to pick ’em out for $2 a pair at thrift stores around the neighborhood. I’ve always liked to curate my own look, go with what I like. I’m not a big follower.”

Today, pro sports is in the midst of a style renaissance, and the NBA is its most fashion-forward league. Every night, superstars such as LeBron James, Dwyane Wade, and Amar'e Stoudemire turn the postgame news conference into a runway, greeting the cameras in Michael Bastian, Givenchy, or Alexander Wang. Offseason, you're as likely to spot them in Paris or Milan as in the gym.

But no athlete in any sport has cultivated a more distinctive style than Westbrook. Head-to-toe monochrome red outfits? Check. Elephant-print jackets? Sure. Acid-washed coverall shorts? Wore 'em on Jimmy Kimmel Live in September. (Think I exaggerate? Check out @russwest44 on Instagram.) Westbrook loves mixing high fashion and low, pairing couture with H&M. He won't hesitate to take scissors to a $2,000 shirt if the mood strikes. His outré style has become so famous that when he got married in August, the ESPN headline read: "Russell Westbrook Gets Married, Wears Regular Tux." (It was a Tom Ford.)

Jock traditionalists, it should be noted, have struggled to accept the new fashion movement and its leading icon. “He wears weird s---,” Kobe Bryant said of Westbrook last year. “It’s a generational thing. I’m glad I didn’t grow up in his generation.” On YouTube, Westbrook’s outfits are a source of steady fascination.

Westbrook, who possesses the confidence to wear hot-pink pants, laughs off all of this, which he attributes to insecurity. “Sometimes people ask me jokingly for style advice, but I know they mean it seriously,” he says. He’s happy to oblige. Long before the NBA, back when he was still scouting $2 frames, Westbrook harbored an ambition to one day run his own fashion empire. And not just the star athlete’s typical sneakers-and-video-games franchise, though he has these covered. (Nike sells his shoes, and Electronic Arts put him on the cover of NBA Live 16.)

Westbrook had in mind full-on couture. Through a partnership with high-end retailer Barneys New York, he’s built a brand, Russell Westbrook XO, under which he’s created, with premier designers, everything the modern man of means requires. There’s clothing (with Public School), slippers (Del Toro), fragrance (Byredo), luggage (Globe-Trotter), and jewelry (Jennifer Fisher). He’s also introducing Nike’s multibillion- dollar Jordan Brand, previously known for midpriced athletic wear, to Barneys’s upscale clientele, with pieces he designed, such as a $500 white flight suit.

Born in Long Beach, Calif., Westbrook may have shown more early promise as a fashion figure than a ballplayer. When he arrived at Leuzinger High School in Lawndale, his size 14 feet supported a mere 140-pound, 5-foot-8 frame, and he spent most games riding the bench. But he carefully cultivated a look. Along with the frames, FUBU’s Fat Albert line was an early preoccupation.

ADVERTISEMENT

By senior year, Westbrook had sprouted to 6-foot-2, 180 pounds, and become the starting point guard. But he wasn’t heavily recruited by major schools. Only when UCLA lost its star shooting guard in the 2006 NBA draft did the school’s coach, Ben Howland, make a late scholarship offer that Westbrook accepted. Even then, he was a bit different. He chose “0” for his uniform number and studied fashion blogs and magazines. “In college, a lot of kids don’t do this,” he says, “but I enjoyed dressing up and going to class and getting good grades. Nobody paid much attention then.” They do now, though Westbrook would probably still spend an hour dressing before heading to a game, cycling through four or five outfits, even if they didn’t.

He’s emerging as the creative force he’s always wanted to be at the exact moment when the top labels have become smitten with professional athletes. “We all look to someone for style references,” says Tom Kalenderian, executive vice president at Barneys. “It’s athletes like Russ who are delivering that in the same way musicians and actors once did. They’re making and setting the trends, not just following them. The playing field is the new red carpet.”

Oh — and let’s not forget the frames. After the Great Lensless Glasses Freakout of 2012, the NBA, no slouch in the marketing department, signed a deal with Westbrook’s eyewear startup, Westbrook Frames, to license a line of high-end, team- branded frames. They cost $145 each, and you can wear them with or without lenses.

Westbrook was born to dress people in the same way he was born to drop 40 points on opposing teams. “It’s funny. If you go to my house and look in my closet — I’m not lying — I have seven different piles of clothes, each for a different friend,” Westbrook says, sipping a juice at Fred’s, the sleek restaurant above the Barneys Madison Avenue store. When he isn’t playing ball or designing clothes, Westbrook is outfitting his buddies, operating as a sort of Santa of style. “All my friends, I send it to them, and they’re like, ‘Oh yeah. This is me.’ They don’t have to ask, I just send it to them: That’s for you, that’s for you, that’s for you. …A lot of times, we’ll go out, and I’ll think to myself, ‘Damn, I used to have a shirt like that.’ Then I realize, that’s my shirt!”

Until recently, the dominant fashion in the NBA was a rejection of fashion, or at least high fashion. Players tended to favor jerseys, T-shirts, warm-ups, and do-rags. Then, in 2005, NBA Commissioner David Stern decided to institute a dress code to clean up what he regarded as the league’s thuggish image. His decision, which some criticized for its undercurrent of white paternalism, initially caused a furor. But it worked better than he could have imagined and sent the league rocketing off in a new direction.

“That was when the whole thing started,” says Rachel Johnson, a style strategist at the Thomas Faison Agency, who’s outfitted athletes such as LeBron James, Victor Cruz, and Chris Bosh. As players started dressing up, trends emerged. For a while you couldn’t turn on the 11 p.m. SportsCenter without encountering a parade of NBA prepsters in cardigans, backpacks, and glasses, talking over the evening’s action. Soon, competitiveness kicked in. “The NBA is a never-mentioned-but-everyone-knows-it style competition,” Johnson says. “I’m not in the locker room, but I do know that they talk about each other and have opinions about each other’s style.”

Westbrook cultivates an edgy look characteristic of the younger players in the league that bewilders veterans like Bryant. “I like a slimmer, European cut and fit,” Westbrook says, when we wander downstairs to admire his Barneys line and do some shopping. “Athletic stuff is usually baggy, hanging off you. I want to go in the direction of more fitted clothing that’s still comfortable to wear. It’s important for me to get a different look that separates you from other people, so I’m always thinking about things like color, pattern, silhouette.”

He’s rare among professional athletes in that his world- class skills are contained within a normal-human-size body. At 6-foot-3, 190 pounds, he can buy off the rack, which thrills designers, who don’t have to custom-make his clothes. Even as players embraced couture, many are gigantic, which stood as an obstacle to acceptance. “When I started, I had to beg — literally beg — for any designer to acknowledge my athletes’ existence,” Johnson says. “It wasn’t cool then. In fact, it was unheard of. Designers were so afraid of athletes’ proportions, so afraid their aesthetic wouldn’t translate onto these bodies that they didn’t understand.” She finally took to flying players to Paris and putting them before designers “to see how perfect their bodies are. These guys are beautiful, they’re relatable. Once they saw the players in their clothes, those two worlds came together.”

ADVERTISEMENT

It helped that GQ and L’Uomo Vogue started putting players such as James on their covers. “They really put athletes on a pedestal,” Kalenderian says. “In the ’60s, the image of the perfect man was found at the movies. The archetypes of style were actors like Paul Newman, Steve McQueen, and Robert Redford. Now young men look to social media, to Tumblr and Instagram, where they see athletes like Russell Westbrook.”

New York Fashion Week was testimony to how thoroughly Westbrook's worlds have mixed and to the influence athletes are having on top designers. Athletic concepts such as sneakers, sweatshirts, hoodies, and T-shirts have become staples in every designer collection, including Chanel and Givenchy. "I live in gym clothes," designer Alexander Wang recently told the New York Times. "When you go out on the street, it's the uniform now." The trend cuts both ways: Nike has hired Givenchy's Tisci to create a line of sneakers.

The industry buzzword for this mashup of formal and athletic wear is athleisure. “Take something like sneakers,” Kalenderian says. “It’s astounding how many people in different industries find themselves dressing in sneakers instead of leather shoes. It’s become natural to stretch the rules of what we think of as the traditional male suit of armor. I think that freedom to try new things comes from sport.” Most creative-class employers have loosened their dress codes, and while an outfit of Nike Westbrooks and cashmere drop-crotch sweats may not yet fly at Goldman Sachs, even bankers have occasion to loosen up. “Maybe the Goldman guy is wearing that on Saturday or Sunday,” Kalenderian posits.

For star athletes, fashion has become more than a hobby. It’s a critical component of their public identity, their “brand soul,” as Marc Beckman, Westbrook’s business partner and principal at creative agency DMA United, calls it. Westbrook’s image as a risk taker and innovator could serve him well in the fashion role he envisions for himself once his playing days have ended. The fleeting nature of athletic celebrity will make this difficult. Only Michael Jordan has built a fashion empire that’s outlasted his playing career, and his has been limited to athletic wear. Westbrook has similar plans, but he’s starting with high fashion.

“Right now,” he says, “I’m taking steps to get there. It’s a learning process. You have to be committed to going out to meet different people, having your ears open, not thinking you know everything about fashion. The creative stuff, I think, comes from within.”

“I’m always thinking about things like color, pattern, silhouette”

What Westbrook won’t compromise is his brand soul — and that includes his belief that fashion should be accessible to everyone. This is why, in addition to his Barneys line, Westbrook has also become campaign creative director for the True Religion denim brand, which sells $200 jeans. Two days after the Givenchy show, he’s greeting a line of fans that stretches out the door of the True Religion store in SoHo. “It’s important for me to stay close to my roots,” he says. “I wasn’t always able to afford shirts that cost $2,000. I want to be able to relate to the people I grew up around, the people in my neighborhood, inner-city kids, anyone who wants to dress nice and might not have money. Mixing high and low gives people a sense of how to do it without spending too much.”

At the photo shoot for this story, he was surprised to see the brand-new, white, faux-snakeskin Jordan Westbrook 0s — so new he didn’t yet own a pair. (He pulled up the images on his phone to be sure.) Afterward, Westbrook, forever the trendsetter, had a final request. “You don’t mind if I take those with me, do you?” he said, smiling and nodding at the shoes. “I’m going to take the blue pair, too.”

With the proper guidance, he believes, any man can learn to look good. Well, almost any man. “Barkley can’t dress to save his life,” Westbrook concedes. “I’d just keep him in T-shirts.”

By Joshua Green; editor: Emma Rosenblum.

From analysis of the global fashion and beauty industries to career and personal advice, BoF’s founder and CEO, Imran Amed, will be answering your questions on Sunday, February 18, 2024 during London Fashion Week.

The State of Fashion 2024 breaks down the 10 themes that will define the industry in the year ahead.

Imran Amed reviews the most important fashion stories of the year and shares his predictions on what this means for the industry in 2024.

After three days of inspiring talks, guests closed out BoF’s gathering for big thinkers with a black tie gala followed by an intimate performance from Rita Ora — guest starring Billy Porter.