The Business of Fashion

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

NEW YORK, United States — Irving Penn's 1950 photograph of Lisa Fonssagrives-Penn, his wife and muse, is quietly complicated. There's the absolute stillness and triangular proportion of her gravity-defying pose, which is seemingly undulating and uncomfortable, homage perhaps to the rigorous Edwardian S-silhouette, yet simultaneously weightless and zen. The structured Rochas gown and translucent chiffon shawl is offset by soft, murky daylight, however a shadow looms in the top left corner, akin to a stormy Renaissance landscape dramatically orchestrated by a divine hand. And beyond all the high-chic froideur, the trappings of the studio are consciously present as a pertinent reminder of the photographer's visual craftsmanship — this is not just an ideal; it's real, Penn seems to be stressing. The result is a powerful image with a depth and formality imbued with the reality of post-war life; a quintessential mid-century fashion photograph.

Penn was clearly not just a fashion photographer and his oeuvre was unrestricted by genre. Such was the brilliance of his eye that Edna Woolman Chase, the white-gloved editor of American Vogue during the first half of the 20th century, said that his photos "burned through the page"— and she didn't mean it as a compliment. Decades later, Penn's mentor and friend Alexander Liberman, editorial director of Condé Nast from 1962 to 1994, described his singular images as "stoppers" — images so visually arresting that they stopped you from turning the page. Beyond the regal couture-clad models in Balenciaga and Dior, however, the New Jersey-born photographer's innovations were countless and his sympathetic Rolleiflex lens would cast a blue-collar craftsperson and an indigenous native in the same fascinating light as a Hollywood star or illustrious literati.

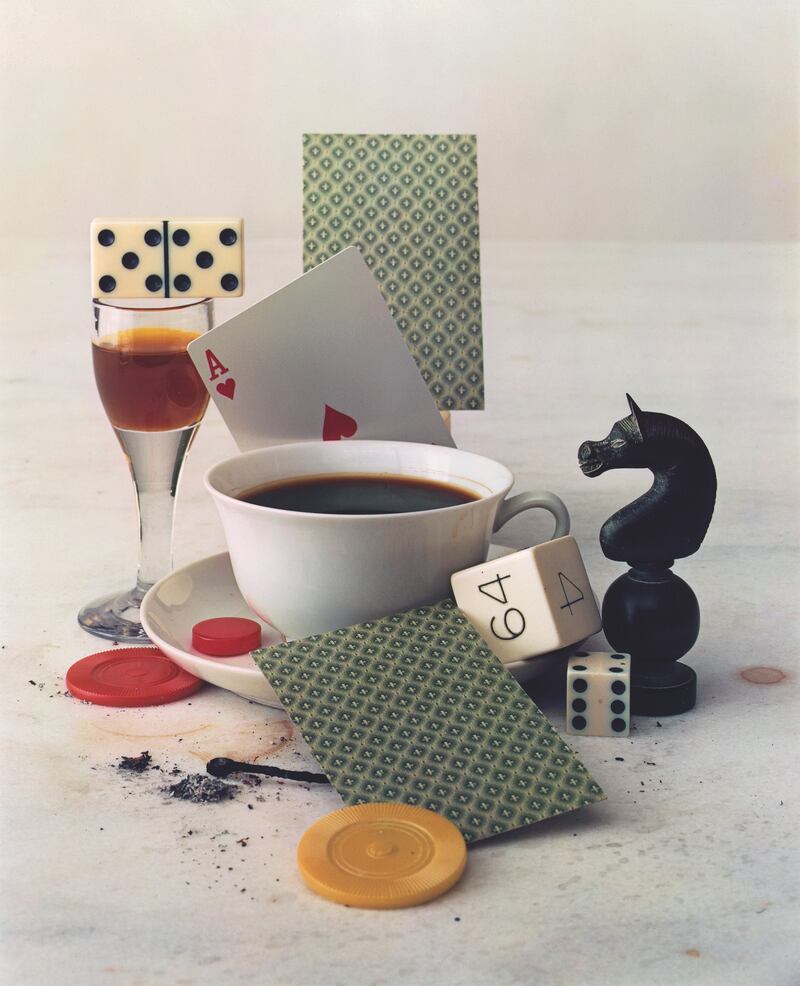

In 1944, Penn began photographing portraits of notable figures for American Vogue, often for the "People Are Talking About" section, and he approached them with a modernist curiosity that sought to shake up Vogue's focus on genteel society. His stark use of cornered backdrops and dishevelled carpets and stools became a modernist antidote to the opulent backdrops and polished composure of yesteryear. His painterly use of daylight, too, had an element of dark realism. It's here that we see a close-up of Picasso, closer than we see ourselves in the mirror, as well as subjects in uncomfortable positions that strip away the glittering façade of a silver screen or newspaper clipping. Penn's still lifes, too, evoked the aftermath of human experience (a lipstick stain on a glass of wine or detritus recovered from the gutter, for example). He was quickly carving out a space in the magazine that offered an alternative to the distilled beauty seen throughout the rest of the magazine.

“Penn wanted to undermine the idea that whatever’s in the picture is the sort of ideal condition and the lasting condition, especially in a magazine about beauty,” says Maria Morris Hambourg, co-curator of "Irving Penn: Centennial," the largest ever retrospective of Irving Penn’s photography, set to open at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art on 24 April. “Penn wanted to undermine that because if you’re an artist and your experience shows you that the world is a much more complicated place, how could you pretend? You only have to dive into the right literature to understand that post-war, it was an existential moment and the world as it was known had come to an end and many people had suffered. Because of Penn, we now see flowers that are dying as beautiful things and his vision of the reality of life and death is what makes his work so profound.”

ADVERTISEMENT

After-Dinner Games, New York, 1947 |

Source: © Condé Nast, Irving Penn

Penn was also a true innovator. He introduced strobe-lit white backdrops that evoked the blankness of a page and echoed Liberman’s vision of a magazine for the modern world. There were also the witty pictures of artfully styled food and fresh ingredients; the dramatic portraits that captured the intoxicating allure of a New Guinea tribesman and veiled Bedouin maidens. Later in his career came high-impact beauty stories that veered towards extremity — a model drenched in milk to illustrate a story on face creams or a plump bumblebee on a scarlet pout as a riff on ‘bee-stung lips’ — as well nudes of Rubens-esque and morbidly obese women, some of whom Penn attempted to politely cast from the street, only to be threatened with being reported to the police. There were also several personal projects focusing on still life and platinum-printed nudes, as well as advertising work for Clinique (the longstanding collaboration continues to inform the American brand’s advertising today) and a collaboration with Japanese designer Issey Miyake, which began in 1986 and lasted for over a dozen years.

However, Vogue was Penn's principal platform and lifelong employer, mainly because, as British fashion photographer Norman Parkinson remarked, "a photographer without a magazine is like a farmer without a field." It was the magazine that was his main source of income, and his earlier years spent as the assistant to Alexey Brodovitch, art director at Harper's Bazaar from 1934 to 1954, meant he had an inherent knack for creating photography that leapt off a page — whether that was a portrait, ethnographic study or a picture of Jell-O, for which Penn briefly created advertising imagery. "Certainly, Alexander Liberman never believed in photography as an art with a capital-A," insists Morris Hambourg. "And he didn't want Penn to get waylaid into avenues of fine art. He wanted Penn to be the artistic, craftsman journalist, and the journalist aspect was an important part of it."

"What he did with Liberman has transcended the medium that it originated in," says Robin Muir, an exhibition curator and contributing editor at British Vogue, who describes meeting Penn as being "face-to-face with history." "He brought art into fashion photography and gave it a rigour and clarity that hadn't existed since Steichen. He spoke about it as though it was up there with fine art, which was rare because a lot of fashion photographers treat fashion photography with indifference, as though it's beneath them. I found that a lot with [Lord] Snowdon, and even people like Mario [Testino] are at pains to show you their other work. They publish these wonderful books of outtakes and 'stuff I do for myself' and the fashion side of it is always slightly undignified."

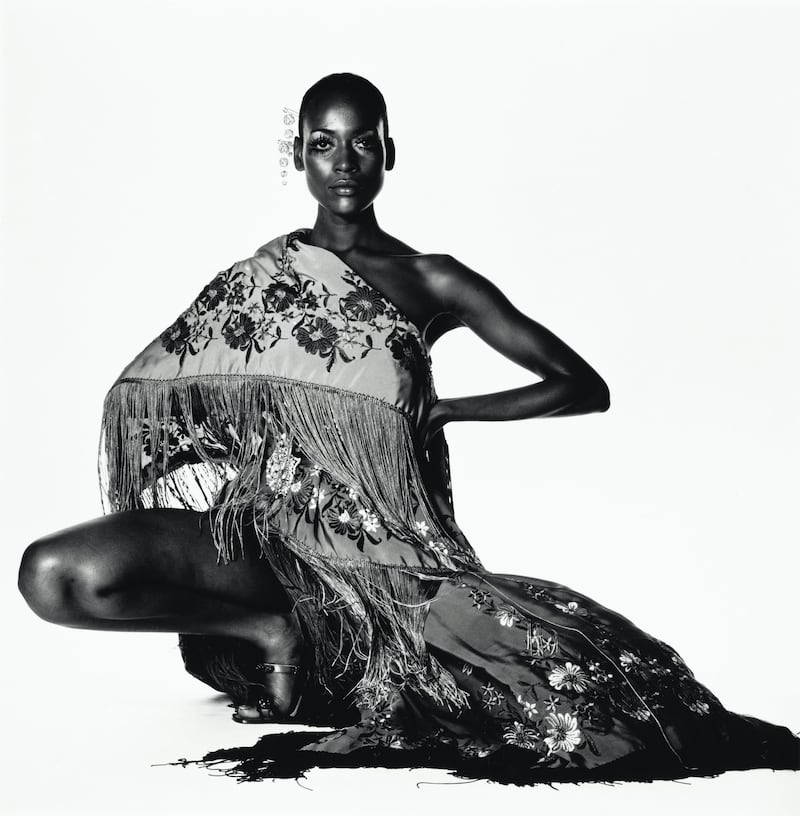

Muir is the first to admit that despite Penn's perennial halo, there were stages in his career that were below par, namely the 1960s. By then, Vogue was struggling and the the book had shrunk in terms of both format and number of pages. The result was a less effective medium for precious photography; it was more of a stage for Diana Vreeland's elevation of youth, colourful pop culture and fizzy jet-set society. "I don't think he could understand the kooky Diana Vreeland world — it was all Veruschka and big hair, and that wasn't him," says Muir. Maria Morris Hambourg agrees. "She was the exact opposite of Penn, who was so classical and controlled," she adds.

When Vreeland brought Richard Avedon (her former collaborator at Harper's Bazaar and Penn's rival) to Vogue in 1962, it was a point of tension for Penn. "Avedon was much more in sync with her style," Morris Hambourg says. "I think that was a hugely disturbing entry for Penn to have his arch competitor right on his turf. I think it was a turning point for him, to turn away from the pages and more into his own art, and I think he felt it was a demotion in a sense."

By the 1970s and '80s, Penn was doing more high-impact work for the magazine once again with striking portraits and dramatically singular images that accompanied features on beauty, health and food. Avedon, meanwhile, photographed the heavily caked headshots that appeared on almost every cover, until Anna Wintour arrived as editor-in-chief in 1988, and reinstated Penn as the magazine's resident colossus. "At that point in his career, Penn wasn't interested in just taking another picture," says Phyllis Posnick, Penn's trusted sittings editor at Vogue. "He wanted to expand the oeuvre of his work and Anna wanted a Penn photo in every issue." Penn returned to using natural lighting in 1995, and his unretouched photos, which were achieved with hours and sometimes days of monastic stillness, once again became a powerful antidote to glossy, commercial photography that filled most of the pages of the magazine — right up until his death in 2009.

Here, six of Penn’s closest collaborators — Polly Mellen, Marisa Berenson, Issey Miyake, Phyllis Posnick, Julien d’Ys and Caroline Trentini — who worked with him from the 1960s to his final years in the late 2000s, share their experiences of the mysterious photographer.

ADVERTISEMENT

Naomi Sims in Scarf, New York, ca. 1969 |

Source: © Condé Nast, Irving Penn

Polly Mellen

92-year-old Polly Mellen began at Harper’s Bazaar, under the legendary Carmel Snow, before revitalising Vogue with Diana Vreeland and subsequently working under Grace Mirabella and Anna Wintour. She began working with Irving Penn in the 1960s, often on portfolios of haute couture.

"When I think of Penn, I think about perfection, discipline and great respect. I did very few sittings with him that weren't in a studio in Paris or New York City. There was also a time when Penn agreed to photograph Chanel's collection, and it was organised by Mrs. Vreeland and Alexander Liberman in Paris. Coco Chanel was alive at the time and she insisted on using her own models. Penn said, 'Polly, I can't photograph them — they're ugly!' And they were. He said, 'I appreciate the clothes, but I can't do it on her girls.' So, finally Alex Liberman, his great friend, talked him into using Coco's girls, because she wouldn't let us have the clothes otherwise. When we were doing the shoot, I saw what was happening — 'Oh my God, he's cropping them at the neck!' He photographed them so that either one of them was turned around at that point, or turned away. He knew exactly how to do it so that their heads were not in the picture. The pictures were wonderful. Penn always got his way."

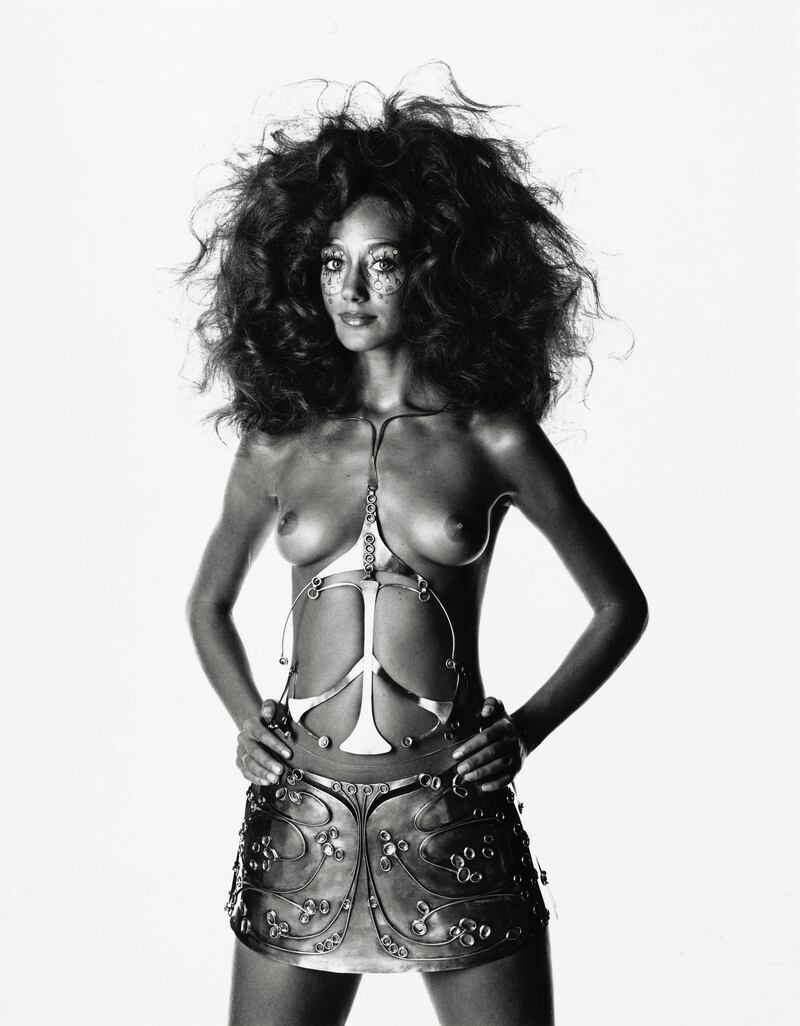

Ungaro Bride Body Sculpture (Marisa Berenson), Paris, 1969 |

Source: © Condé Nast, Irving Penn

Marisa Berenson

Marisa Berenson, granddaughter of Elsa Schiaparelli, was ushered into the world of modelling upon meeting Diana Vreeland as a teenager. Irving Penn repeatedly photographed her against a white backdrop throughout the 1960s, and she also worked closely with Richard Avedon. Berenson posed for the first nude to be published in Vogue — in 1969. She would later become an actress, starring in Stanley Kubrick's "Barry Lyndon" and Luchino Visconti's "Death in Venice".

"Diana Vreeland loved the way that Penn photographed me, and at the time he was in every issue of Vogue, so we began working together and I worked with him more than anyone else in the '60s. Being photographed by him was like being a still life. One had to sit for hours in a pose and it was like a sacred experience in a church. There was never any music; everything was very quiet; there was no smoking or laughing, there were very few people in the studio — only one assistant and maybe one editor — and in those days we did mostly our own makeup, except for exceptional sort of hair and things like that. It was much more fun to be photographed by Avedon! With Avedon, you were jumping all over the place and full of energy and full of life, but Penn was much more of a still person. Avedon had a great bubbly, fizzling personality and he loved to go out a lot; Penn was much more of an introvert in his own completely different world, which was very interior.

ADVERTISEMENT

"In 1969, a jewellery designer called Jose Barrera went to Diana to show her his work and she loved it, and asked him how he would photograph a particular necklace. 'Well, on my wife I'd photograph it nude,' he said, and Diana said, 'That's it! And Marisa has to do it.' I had never posed nude before and Vogue had never published a full nude before, but I must say with Penn you never felt uncomfortable doing something like that, because it was like being painted by Botticelli or Boucher or Rubens. He was such a gentleman, so it was not like doing a graphic photograph at all. He was just a natural and you just felt that he was creating a work of art. When it came out, Avedon sent me a sweet telegram congratulating me on a beautiful spread. People thought it was beautiful — except my grandmother, who wasn't too happy about it. She didn't think a girl from a good family should be modelling naked in Vogue! But in the 1960s and '70s, there was a huge change in lifestyle, in joie de vivre, and everybody could express themselves the way they wanted. It was a great time for creativity."

Two Miyake Warriors, New York, 1998 |

Source: © Condé Nast, Irving Penn

Issey Miyake

Tokyo-based designer Issey Miyake emerged in the 1970s as creative force in New York and Paris, creating a sculptural aesthetic that combined eastern and western sensibilities. His collaboration with Irving Penn, one of the photographer’s personal projects, began in 1986 and lasted for over 12 years.

“I first became aware of Mr. Penn through his photographs when I was a student. I was in awe. I saw there their power to convey the truth and his photos have a raw power, energy and honesty. My collaboration with Mr. Penn began in 1986, and the relationship we had was what we call A-UN [the first and last letters in the Sanskrit alphabet]. For me, it’s my A and Mr. Penn’s UN. His UN in turn becomes my A, and is returned to me by Mr. Penn. Sometimes I am amused to liken our relationship to that of Nio, the two fearsome gods standing guard before the gates of a Buddhist temple, forever engaged in their own silent communication. It is a silent communication.

"We did not work together in a traditional sense. I sent my collection and my right-hand man, Midori Kitamura, to New York and trusted Mr. Penn to make his own selections and shoot the clothes as he saw them. What he sent back in the form of photographs was his trust, his thoughts, his comments and his vision. Each photograph always filled me with surprise and joy and seeing my designs through his eyes always gave me new perspective, and gave me new ideas and new energy with which to move forward. He would make these wonderful drawings before a shoot, and I remember his love of simple food like macaroni and cheese. When I think of Mr. Penn, I think of Sensei.”

Cult Creams, New York, 1996 |

Source: © Condé Nast, Irving Penn

Phyllis Posnick

Phyllis Posnick, executive fashion editor of Vogue, first met Irving Penn as an assistant at the magazine in the 1970s. She began working with him at the request of Anna Wintour and Alexander Liberman, becoming his trusted collaborator on still life imagery to accompany features, as well as striking fashion photographs, that Alexander Liberman coined "stoppers". Posnick was Vogue's last sittings editor to work with Penn.

“About a year after Anna [Wintour] became editor-in-chief, she asked me to work with Penn. She and Alexander Liberman thought we would be a good combination. Alex had written, 'Penn is not easy to work with. The most difficult moments involved getting though his very special resistance and hesitation in taking a picture.' And was he ever right! At that point in his career, Penn wasn’t interested in just taking another picture. He wanted to expand the oeuvre of his work. Anna wanted a Penn photo in every issue, but it took time for me to learn to work with him and our early collaborations weren’t our best. After our first sitting (never a shoot!), we began to talk almost every day about the next shoot, and the next. I would go to his studio and tell him about the article we wanted him to illustrate or the fashion we hoped he would photograph. While I talked, he would draw — often something completely spontaneous that seemed to have nothing to do with the subject ... But it did. He could be stubborn, difficult, perverse, but he was also patient, prodding, kind, and subtly gave me openings to say what I thought. Often it took more than two months from our first conversation to the day of the sitting.

"In 1995, we were planning to photograph couture in Paris and I asked Penn if he would consider the type of available light he'd used in his iconic '50's pictures instead of strobe light, which he was using for our sittings. He said, 'Yes, but only if you can find the studio I used in Paris with light coming through the dirty skylights. The studio was long gone but thankfully our Paris editor found one just like it. Using daylight again transformed his photographs and it’s when we began to do our best work together. The only time he used strobe after that sitting was when he did still life for food articles. I suspect he had the most fun creating the still lifes because there was no beautiful model or hair or makeup artist to distract him. I’ve read that Penn would need "hundreds of lemons" to find the perfect one for his photo. That’s wrong! It was never about finding the 'perfect' lemon. It was about which lemon was perfect for his picture. That lemon could be rotten and still be perfect for him. I’ve also heard people say that his studio was like a cathedral, but there was joy and laughter and a squeaky floor in that cathedral.

"We talked for hours and hours about everything from silly things on late night TV to politics (he was a rebel) to where fashion and magazines were going (not as good as the 'old' days, he thought) to why young women wore such clunky shoes (who knows? it's fashion!) to how his photos fit in the modern Vogue to stories about his wife, Lisa, and about our aches and pains — my shoulder, his foot. At lunch one day I told him that my shoulder was so painful, it was difficult to lift a fork. 'Perhaps you should try to put less food on it,' was his reply. He had a great sense of humour and a brilliant mind.

"He changed my perception of what I thought was beautiful. One time we were arguing about the direction of a picture. I was resisting him because I was afraid that his idea for the photo was too extreme and it would be killed. He told me that he would prefer to have a photograph killed because we dared to do something different, than to have a mediocre one published because we didn't. I have this in my mind now every time I shoot and when I’m shooting now, I hear his voice: ‘It's too NICE!’ or ‘It's BITSY!’ Sometimes when I can't think of what to do, I wonder ‘what would Penn do,’ but I can't imagine what Penn would do, because he'd never do what one expected.”

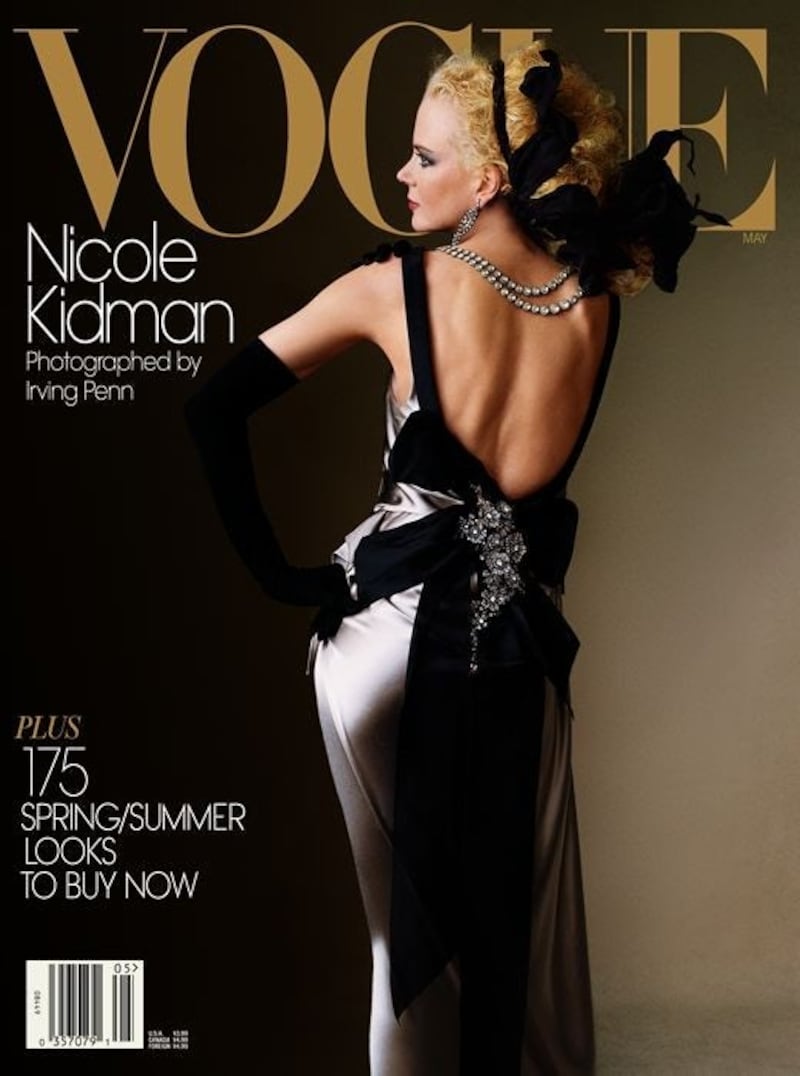

Vogue, May 2004 | Source: © Condé Nast, Irving Penn

Julien d’Ys

Julien d’Ys is a renowned “hair artist” who worked with Irving Penn on a number of sittings for Vogue during the 1990s and 2000s. His longstanding collaboration with Comme des Garçons and John Galliano set him apart from commercial stylists, and he has been charged with headdressing of the mannequins at the annual exhibitions at The Met’s Costume Institute since 2005.

"Every time I worked with Irving Penn, it was exceptional. I had my corner with all of my stuff. When I was arriving, he would show me my table and I'd arrive with every kind of material, glue, paint and hairpiece, every material to build something new with. I never knew what we would do. It would be spontaneous. Sometimes, it was over the top — he would it want it to look like clouds, for example. One shoot I remember a lot was of Cate Blanchett as Elizabeth I. Pat McGrath was doing the makeup and everything was done using daylight. When I was looking at him, he was slowly moving as the light was changing. It was very ceremonial. There was no computer and no retouching, and absolute silence. We could hear the floor creaking whenever anyone walked and we would just hear his quiet voice saying 'see something,' and the look on the face would change.

"Sometimes I work with photographers and what I see in front of me is what I want to see on the paper, but it all gets changed. With Penn, everything that you saw was what the picture would be, without retouching. You had to be good to work with him — once he came out and looked at the hair, and said 'I see nothing,' and I had to start over again. I learnt a lot from him, like how to consider the angle of the camera when he was shooting from below. Every strand of hair or every piece of ribbon was important to him, so everything had to be done the right way. When he photographed Nicole Kidman for the cover of Vogue, he said there couldn't be any writing on the picture — and they did it. That was amazing! In a way, it was like working with Rei Kawakubo. Even now, I'm doing the mannequins at The Met for Comme des Garçons and some pieces just make me always think of Penn. I think, 'He would love to shoot that.'"

Caroline Trentini

Towards the end of his life, Penn was working sporadically on special images for Vogue and had a reputation for working with a few models who could sit for hours. During the 2000s, Brazilian model Caroline Trentini became his favourite, and she sat for him in majestic portraits that often showcased extravagant custom-made gowns or costume-like couture, until his death in 2009.

“I started working with Irving Penn when I was still in my early 20s and obviously I was so nervous the first time, and he just came in like this old friend and spoke to me so gently and so politely. I fell in love with him because I had this image of this powerful man, but everything about him was so loving. New York City was so hectic and his studio was so calm and peaceful. His studio was like a place of peace, where everything moved slowly and was just so calm. When we were shooting, I would just be so connected to him that I couldn’t hear anything else in the background, you know like the ambulances outside. I would just lock myself in that place and he would put me in the mood by very quietly saying ‘see something beautiful’ or ‘see something harsh.’

"Before the shoots, we would do a rehearsal with the clothes, but no makeup or hair and he would take Polaroids. Then on the day of the shoot, he’d know exactly what he wanted to do, and if he wasn’t satisfied then we would just continue the next day. He had the exact image in his head and would do a drawing, and then he wouldn’t stop until he got it. By then he was quite old and there was a little bed in the studio for him to take rests between shooting. Things are a lot different now. Today, who does a rehearsal for a shoot? And who is going to say, 'No, we’re going to try another day,' if they’re not happy with the image? Usually, with a lot of photographers you never know what you’re going to get, and the photographers decide as they go along. Penn had a way, and it was his way, and everybody respected that.

"I remember going home with that crazy hair and makeup sometimes, looking at myself in the mirror with my regular jeans and t-shirt and I'm thinking, 'I can't believe this happened to me.' I remember Phyllis telling me that he thought of his wife when he saw me in one of the photographs and that made me cry. One of the last shoots that we did, I arrived a bit early and went to a café outside his studio. I sat down to have my coffee and I saw him walking by very slowly, on his way to the studio. He was in his button-down shirt, jeans and with his comfortable shoes — the kind you wear inside when it's cold. Everybody was just walking past him, and he would just very calmly take his time. That memory is one that I'll always cherish."

"Irving Penn: Centennial" opens April 24 and runs through July 30 at The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

From analysis of the global fashion and beauty industries to career and personal advice, BoF’s founder and CEO, Imran Amed, will be answering your questions on Sunday, February 18, 2024 during London Fashion Week.

The State of Fashion 2024 breaks down the 10 themes that will define the industry in the year ahead.

Imran Amed reviews the most important fashion stories of the year and shares his predictions on what this means for the industry in 2024.

After three days of inspiring talks, guests closed out BoF’s gathering for big thinkers with a black tie gala followed by an intimate performance from Rita Ora — guest starring Billy Porter.