The Business of Fashion

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

NEW YORK, United States — On the second Saturday in January, The New York Times Styles reporter Matthew Schneier was waiting for the Versace men's runway show to begin inside the brand's palazzo on Via Gesu in Milan when, just before the lights dimmed, an editor sitting across the runway glanced at his phone, looked up at Schneier and blanched.

The editor, who Schneier did not name, had a long history of working with photographer Mario Testino, and The New York Times had just published an article detailing allegations of sexual misconduct spanning decades by both Testino and Bruce Weber, two of fashion's longest working and most revered photographers. The report, over three months in the making, represented the cumulative efforts of Schneier, Styles reporter Jacob Bernstein and fashion director and chief fashion critic Vanessa Friedman.

The next day, the article made the front page of the paper’s Sunday edition, above the fold, with the headline: “‘I Felt Helpless’: Male Models Accuse Photographers of Sexual Exploitation.”

The story had instant impact on both sides of the Atlantic. Brands and magazines quickly distanced themselves from both men. Fashion publishing powerhouse Condé Nast, which had long-time contracts with both photographers, said it wouldn't work with either "for the foreseeable future." Michael Kors, Burberry and others echoed those statements.

ADVERTISEMENT

Representatives for both Weber and Testino said they were “dismayed and surprised by the allegations,” according to the Times article. Weber denied the allegations. “He denied the claims being made, and continues to deny those claims in the strongest of terms,” a lawyer for Weber tells BoF.

Testino’s lawyers said in a statement sent to the Times in response to queries that the men who spoke with the paper “cannot be considered reliable sources,” and called into question the mental health of one of the accusers. The representatives also said several former employees were “shocked by the allegations” and that those employees “could not confirm any of the claims,” according to the Times article.

More sources spoke to the Times reporters after publication, and the paper published a follow-up story on March 3 entitled, “Many Accusations, Few Apologies.” The Boston Globe published its own investigation into fashion creatives on February 16, detailing allegations of sexual misconduct by photographer Patrick Demarchelier — who told the paper he never touched a model inappropriately — and others.

For the Times team, the front-page treatment and widespread coverage of the report underscored the significance of the story. “You didn’t have to be a super ‘fashion person’ to have been exposed to Mario’s work or Bruce’s campaigns,” says Schneier.

You didn't have to be a super 'fashion person' to have been exposed to Mario's work or Bruce's campaigns.

But then, momentum slowed. And larger questions still remain.

If the allegations have merit, then how could the alleged behaviour have gone on for so long without anyone in the industry standing up against it? Friedman believes the answer has a lot to do with the culture and unstructured nature of the fashion business. There are many different and distinct players in what she calls the “supply chain,” including publishers, brands, photographers and agencies that can “wall themselves and their responsibilities off.” Models are arguably at the bottom of that supply chain, especially early in their careers, with no leverage or legal workplace protections.

While The New York Times and New Yorker articles that first published allegations of sexual abuse against Hollywood producer Harvey Weinstein kicked off a cascade of coverage, public outcry and the #MeToo movement that empowered a sea of victims to speak out against sexual misbehaviour by men in positions of power, the fashion industry appears to have shrugged and moved on — albeit without some of its top photographers.

Was this the reaction the Times team wanted? Each of the reporters sees it differently.

ADVERTISEMENT

“The goal is partly to stop misbehaviour by telling the story, that it’s happening, and to allow the people who are actors then to take ownership of that and to change things,” says Friedman.

“This is not a kind of activist piece,” adds Schneier. “This is not a polemic. We thought this rose to the level of news, and it’s for the reader to decide how she or he feels about it. And it’s for the industry to decide how they react to it.”

It’s unlikely that many in the close-knit fashion industry were surprised by such allegations. After all, whispers of impropriety between photographers and models were nothing new. But post-Weinstein, journalists at the Times felt a new imperative to pursue underreported stories of sexual harassment — and the alleged victims felt hopeful that speaking out could drive change.

Starting in October after the first Weinstein reports were published, and after allegations against Terry Richardson resurfaced later that month, a wave of sources reached out to the Styles desk. Someone who promised to connect Bernstein with models who had allegedly suffered abuse telephoned him and “basically said, ‘Why aren’t you doing your job?’” he says. Testino was the first name mentioned. Friedman had already been re-examining Richardson, the subject of sexual misconduct allegations for years, and soon the entire Styles fashion team, including Elizabeth Paton in London, started looking for more information on sexual misconduct among fashion’s top photographers.

“I always felt it was something in the fashion industry where people had whispered it, and it was one of these things that everybody sort of knew, and nobody had really investigated that strenuously,” says Schneier.

It was one of these things that everybody sort of knew, and nobody had really investigated that strenuously.

“The Times is a paper that believes in flooding the zone and putting everybody on the story,” says Friedman. “So, we were all looking into this pretty much from the start.”

And so began a series of conversations with male models and former assistants. The reporters had to convince them “of our seriousness and of our good intentions,” recalls Schneier, adding that the reporters “ended up all weaving [the accounts] together and keeping in constant contact” during the process.

Some of the alleged victims had never shared their stories with anyone before. Many were ashamed and embarrassed, since they saw their experiences as an assault on their masculinity.

ADVERTISEMENT

The reporters also spoke to working models who said that speaking out would be “career suicide,” notes Schneier. Others were apprehensive about the impact. “These were people, certainly in some cases, who felt that they had in the past been ignored or that their experiences weren’t significant… that this is just how modelling was.”

While the fallout following the first Weinstein pieces proved that powerful people could be taken to task for years of misconduct, the decision to speak on the record about personal experiences is never easy.

Bernstein remembers one source who told him a “harrowing” story, and then told him the next day he couldn’t use it. “That certainly made me more determined in some way because it just was a heartbreaking story about being manipulated and abused,” he says.

Schneier spent the day before New Year’s Eve on the phone with one model source who had evidence to support his account. He ultimately pulled out of the story. “The only thing to do was make another 100 calls and hope that you get a 10 percent response rate,” he recalls. But many of the people he spoke with said they had been “waiting for this call for 10 years.”

“As soon as someone said that to me I said, ‘Okay, this is a story,’” Schneier continues. “We’re not fishing for this. We’re not making this up. This is buried but it may be ready to come out.”

The reporters also had to contend with the fact that fashion is fundamentally rooted in selling sex, which, in turn, informs the way models feel about their jobs and can feed self-doubt, shame and a feeling that they were, in some way, complicit in their mistreatment.

“If they’re there effectively promoting their own desirability then that does raise questions of, ‘Okay, how culpable am I in whatever then happens to me?’” says Friedman. “This is something we wrestled with a lot.” Friedman spoke to editors, agents, managers and others about “the fuzziness of fashion, and the complications of dealing with sexual harassment in an industry that is premised on the selling of desire.”

The front page of The New York Times' Sunday edition | Source: Courtesy

The team did not shy away from reporting episodes that revealed that ambiguity such as, for example, when model Ryan Locke told the reporters that Testino climbed on top of him while lying in bed during a Gucci campaign shoot. "We told [those stories] with attribution because we felt that readers could make up their own minds and that the grey area was part of the story here," explains Bernstein.

“This is not a case where you know we are putting the fashion industry, or the way that certain brands shoot campaigns or shoot content, on trial,” says Schneier.

While other photographers came up during the course of the investigation, the Styles team focused on Testino and Weber because the allegations suggested long-standing patterns of bad behaviour as well as recent episodes and clear abuse of professional power: men claimed they were being asked to put themselves in charged sexual scenarios beyond the scope of their commissioned work, for which they were not hired or prepared.

“These were photos that were never seen again, these were auditions for shoots that were never booked, these were private assignations on lunch hours of commercial jobs,” says Schneier. And the situations were used as lures for promised future commercial work.

“It was extraordinary, the similarity in the stories from people who were working with photographers decades apart and across the country; they were not talking to each other, they didn’t know each other,” says Friedman. Other times, those who spoke to the Times personally encouraged other models to speak to the reporters.

Conversations with sources continued throughout the late autumn, as did efforts to corroborate their stories by verifying facts and speaking to those with direct knowledge of the incidents — some of whom had not spoken to the alleged victims in years. “We corroborated every detail to the best of our ability and didn’t publish anything specific that we felt we couldn’t stand by,” says Schneier. But, he adds, “there’s not a paper trail on absolutely everything.”

As the investigation continued, speculation began building in the industry about the forthcoming piece. The chatter was a headache for the Styles team, says Bernstein, because it made sources nervous. “It’s really important that these stories be solid and you be committed to them and you can’t be rushed into that, no matter what the rest of my fashion world is blabbing about,” says Friedman. There were also rumours that industry leaders were pressuring the reporters to drop the story, which the Styles team refutes.

By mid to late December, the team had assembled the sourcing they needed to publish a story on Weber, who had been named in a lawsuit by model Jason Boyce filed on December 1, 2017. A second model, Mark Ricketson, made a public claim against Weber a few days later.

These were photos that were never seen again, these were auditions for shoots that were never booked.

So why not go ahead with the story then? They considered it, and while they explain that they did not have a “grand plan” from the beginning about how to approach the story, they wanted to publish a story that spoke to the industry at large and its “culture of entitlement,” not just individual bad actors.

“We thought putting these two major figures together into a more overarching piece that talked about the culture of the entire industry made a stronger point and made it much harder to dismiss,” explains Schneier.

At the beginning of December, however, only one former Testino assistant named Hugo Tillman, who had connected with Friedman, was willing to go on the record about the photographer’s behaviour. In the weeks leading up to Christmas, Bernstein bought several Testino books at The Strand — “the ones where he had photographed men” — and started direct messaging the models on Facebook and Instagram. Only about one in ten responded.

Meanwhile, Bernstein had been having conversations with an advisor to Testino about the possibility of conducting an interview with him addressing the allegations, according to e-mails reviewed by BoF. But the talks broke down. “We really would have been open to them speaking to us and saying this is our side of it,” says Friedman. A representative for Testino said the advisor was never formally engaged by the photographer and was not officially sanctioned to act on his behalf, adding that Testino never considered an interview with the paper.

In early January, the Styles team was focused on writing and editing the story. While they say there was not a specific number of sources needed as a threshold to move forward with publication, they felt confident in the “sheer number” who agreed to speak for the piece: 15 current and former male models who had worked with Weber and 13 assistants and models who had worked with Testino.

“We reported it until we felt that it was absolutely nailed down and ironclad,” says Schneier.

At The New York Times, the process of ensuring a sensitive story is ready — and will pass legal muster — involves consultation with the paper’s main newsroom lawyer, David McCraw, who reviewed the piece and provided comments to the editor.

“Law is a lot like reporting, it’s more art than science,” says McCraw. “It’s not a matter of saying, ‘This is the threshold that has to be met,’ it’s more [about] what have we done to assure ourselves that we have it right.” When reviewing sensitive articles, McCraw looks for a solid belief that the accusations have merit, that the way the story is written does not imply more than what the reporting shows, and that accusations are not framed as statements of fact.

There is a remarkable constancy to the people who really pull the strings and sit at the top of the food chain.

“With public figures, the law is going to protect us as long as we are not publishing with great doubt or publishing with knowledge of falsity,” he says, adding that The New York Times looks for reasons to believe accusations are true, not simply an absence of doubt.

Most libel suits in the US are not typically brought by the main actor in a story, but by minor players, such as a witness who did not speak out, says McCraw. “We will spend a lot of time looking at those.”

In the wake of the Times piece, has the fashion industry actually changed? The careers of Testino and Weber are frozen, but there’s little evidence that the power dynamics between photographers and models that appear to have enabled such behaviour have changed.

“That’s something we’re still looking at and we’re going to continue to look at,” says Friedman. Schneier says he did expect more “follow-up throughout the industry,” but because much of fashion journalism is “features driven,” and avoids controversy, “when something like this happens, it’s not necessarily clear immediately how it’s going to play out and what those changes are going to be.”

It is clear that models do not have more legal protections than they did before the Times report was published. Condé Nast, however, released a code of conduct banning alcohol from sets and limiting the age of models to 18 and older, among other provisions, as explained in a supplementary article published at the same time as the investigation went live. Kering and LVMH jointly established a model charter in September 2017 that restricted the age of models to 16 and older and committed to strict nudity and semi-nudity agreements, among other guidelines. But these measures are not enforceable by law. There is no union for models, and any future legal protections are further complicated by the global nature of the industry; what is enforceable in one country may not be enforceable elsewhere. And male models, who are generally paid less than female models, are even more vulnerable.

Fashion’s power structure remains largely in place. “For all the talk of fashion being an industry of trends, there is a remarkable constancy to the people who really pull the strings and sit at the top of the food chain,” says Bernstein.

And the risks of speaking out remain high. “Editors work with certain stylists who work with certain photographers, and they do tend to do magazines as well as brand campaigns as well as shows — and it’s the same casting directors,” says Friedman. “It’s very intimidating, I think, for people at the bottom of the food chain… We are proud [of the people who spoke out].”

Editor's Note: This article was updated at 9:54 am GMT on 19 September, 2018, to reflect the claim by a representative of Mario Testino that the advisor to the photographer who was in touch with New York Times reporter Jacob Bernstein about the possibility of Testino conducting an interview with the paper addressing the allegations against him was never formally engaged by Testino or his company and was not officially sanctioned to act on his behalf.

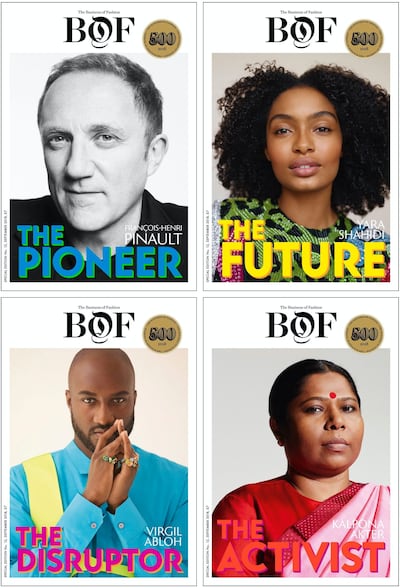

This article appears in BoF's latest special print edition.

To receive a copy of BoF's latest special print edition — including the complete index of BoF 500 members — sign up to BoF Professional before November 2, 2018 and enjoy additional benefits including unlimited access to articles, daily members-only insights and analysis and more with your annual membership.

Related Articles:

[ Bruce Weber Sex Abuse Allegations MountOpens in new window ]

From analysis of the global fashion and beauty industries to career and personal advice, BoF’s founder and CEO, Imran Amed, will be answering your questions on Sunday, February 18, 2024 during London Fashion Week.

The State of Fashion 2024 breaks down the 10 themes that will define the industry in the year ahead.

Imran Amed reviews the most important fashion stories of the year and shares his predictions on what this means for the industry in 2024.

After three days of inspiring talks, guests closed out BoF’s gathering for big thinkers with a black tie gala followed by an intimate performance from Rita Ora — guest starring Billy Porter.