The Business of Fashion

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

Around the time LVMH and PPR (now Kering) were locking horns over acquisition target Gucci, word on the street was that the maximum turnover a luxury brand could achieve before becoming overexposed and losing its lustre was $2 billion. Since then, that number has been far surpassed by luxury’s biggest names, including Chanel, Louis Vuitton, Hermès and Gucci itself. Last month, Kering announced a medium-term annual sales target of €15 billion for Gucci, almost 50 percent more than its already substantial sales base.

How have luxury brands grown so far beyond the upper limits of what conventional wisdom once deemed possible? And when will the sector’s megabrands run out of road?

Over the last two to three decades, luxury brands have been riding the wave of globalisation, initially focusing on Japan, followed by North America and then the BRICs, with a strong emphasis on China. Indeed, China has been the sector’s primary growth engine for almost 15 years and whilst there are clouds on the horizon owing to the government’s draconian zero-Covid policy, the market will continue to deliver growth.

Beyond China, there is still some potential for growth in North America, as well as significant opportunity in India, where some sources expect luxury goods sales to increase from $5.94 billion in 2021 to over $200 billion in 2030, driven by sustained economic development, policy reforms, internet penetration and the soaring aspirations of a growing middle-class. Other markets such as Brazil (luxury sales of $2.67 billion in 2022 with growth prospects of under 2 percent per year) and Indonesia (luxury sales of $1.66 billion in 2022 with growth prospects of almost 4 percent per year) have yet to deliver but represent long-term opportunities.

ADVERTISEMENT

The aspirational nature of luxury has allowed brands to diversify into cosmetics, perfumes, eyewear, small leather goods and accessories, opening up entry-level price points to a much larger middle-class consumer base while confining their original, core product categories to higher price points, preserving their power as exclusive image-generators. This has been the business model adopted by a plethora of brands with either fashion or leather goods heritages, such as Chanel, Louis Vuitton, Dior and Gucci. Over the last decade or so, top brands have also developed watches and fine jewellery offers. Now, there is potential to explore new category expansion in the metaverse with virtual goods.

Experiential luxury also offers opportunity. Bulgari has teamed up with Marriott to open seven Bulgari-branded hotels to date, with a further five in the pipeline. Versace has teamed up with local property developers in Australia and Dubai to open two hotels. But this is still very much a virgin territory. LVMH has been building a portfolio of brands in hospitality, namely Belmond and Cheval Blanc. Whether that expertise will be used to develop luxury hotel franchises for its flagship brands remains to be seen. Louis Vuitton, with its heritage in luggage and its renowned luxury city guides may be a good candidate.

Nevertheless, a quick examination of the product portfolios of the top 10 luxury brands suggests there are still a few category expansion opportunities to exploit, even for leaders.

According to Bain, the personal luxury goods sector has been growing at an average annual rate of 2.9 percent between 2016 and 2021. That compares to 12.6 percent for Chanel, 17.2 percent for Gucci and 11.5 percent for Hermès. LVMH’s fashion and leather goods division has also increased sales by an average annual rate of 19.3 percent over this period despite the group not making any significant acquisitions in this area.

Historically, the growth of some brands (Burberry is a case in point) has come from bringing licences and franchises in house. This is not the case for top mega brands which have largely been pursuing a full integration strategy for a long time. Rather, they are benefitting from a virtuous cycle of increased recognition and sales at the expense of smaller, lesser-known brands or from still largely un-branded product categories, such as jewellery.

With higher spending power and greater leverage over media, mall owners and wholesale partners, market share consolidation by top mega-brands is likely to continue. The rise of everything digital and the flattening of national barriers by social media is also favouring brands that already have high recognition amongst consumers. This is further compounded in times of crisis or economic downturns when consumers typically turn to safer bets.

Aggressive expansion, while tempting, can sometimes prove to be a trap. Michael Kors, for example, had an amazing run of high double-digit quarterly growth in the early 2010′s only to come off the rails from 2015 onwards as rapid expansion turned the once-hot brand into a has-been almost overnight. Burberry suffered a similar setback in the early 2000s when its signature check was printed on everything from cars to cake tins, and it has taken the brand the best part of a decade to shake off its “chav” image and better position itself to be taken seriously as a fashion trend-setter with more opportunity in leather goods.

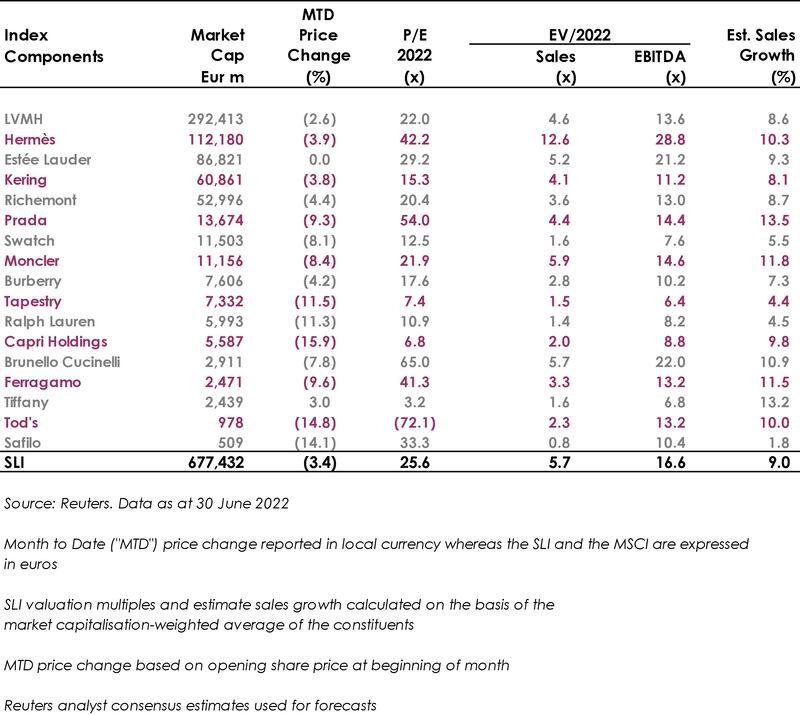

The Savigny Luxury Index (“SLI”) fell 2.5 percent in June driven as the world continues to face challenges in coming out of the Covid pandemic and its impact on cost of living. The MSCI’s performance was worse, posting a decline of 7.4 percent over the month.

ADVERTISEMENT

The metaverse will play an increasingly relevant role in luxury brands’ value propositions going forward. Fashion companies focused on metaverse innovation and commercialisation could generate more than 5 percent of revenues from virtual activities over the next two to five years, according to BoF and McKinsey’s The State of Fashion: Technology report. It will be interesting to see what the craft- and creativity-driven luxury sector will produce in the metaverse, and even more interesting to see how it will monetise this new frontier.

Pierre Mallevays is a partner and co-head of merchant banking at Stanhope Capital Group.

Brands from Valentino to Prada and start-ups like Pulco Studios are vying to cash in on the racket sport’s aspirational aesthetic and affluent fanbase.

The fashion giant has been working with advisers to study possibilities for the Marc Jacobs brand after being approached by suitors.

A runway show at corporate headquarters underscored how the brand’s nearly decade-long quest to elevate its image — and prices — is finally paying off.

Mining company Anglo American is considering offloading its storied diamond unit. It won’t be an easy sell.