The Business of Fashion

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

LOS ANGELES, United States — The silhouette of the moment is rigid and straight, with a noticeably high waist. Not long ago, though, skinny — and stretchy — leggings ruled. And before that, anything other than low-slung and bootcut read passé.

The high-end denim market has long been driven by clear, impossible-to-ignore trends, which is one of the reasons why the segment has managed to sustain growth over the past 15 years while still facing headwinds as heavy as the 2008 financial crisis and the rise of athleisure. The global market for "super-premium" denim — defined as "brands that are located at the top-end of the price range" by Euromonitor International — hit $10.7 billion in 2017.

"Rigid and non-stretch fabrics that were traditionally very tough to sell on a larger scale because of comfort are now appealing to the mainstream consumer," says Joey Laurenti, president of the New York-based Goods and Services showroom, which represents popular denim labels Frame, GRLFRND and Good American. Despite what Laurenti calls a "challenging" retail environment, the showroom has seen denim sales continue to increase year-over-year since it first opened in 2012.

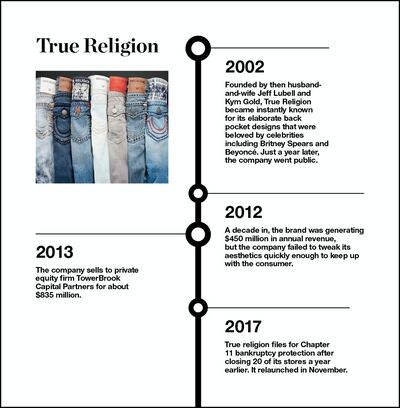

But just as fast as they rise, premium denim labels can face the downside of the adoption curve. Paper Denim & Cloth, Earnest Sewn, True Religion, 7 for All Mankind: these brands were once as hot as GRLFRND and Good American are today. Some have disappeared altogether, while others have gone bankrupt or were forced to move down-market. Many continue to shrink.

ADVERTISEMENT

If the most successful denim labels reflect the zeitgeist, how can a brand remain vital when the zeitgeist shifts?

Illustration by Jan-Nico Meyer for BoF

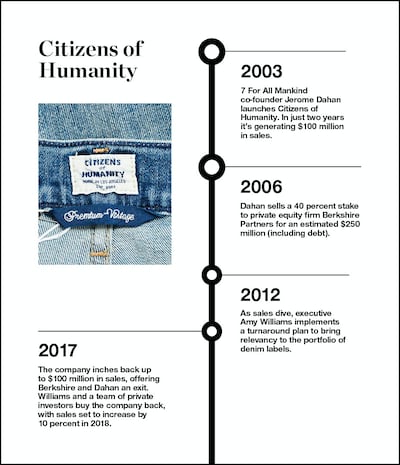

The denim label Citizens of Humanity is currently grappling with this question. Started in 2003 by Jerome Dahan, the industry veteran who co-founded 7 for All Mankind just three years earlier, it was one of the novelty-pocket collections, alongside Diesel and Paper Denim & Cloth, that kickstarted an entirely new market. Premium denim was pricier — and therefore more exclusive — than traditional mainstays like Levi’s, but came with flashy pocket details and distressed finishes made to complement the bedazzled, logo-driven fashion and accessories that defined early-aughts style.

Dahan unleashed Citizens of Humanity just as the market was heating up. Within two years, it was generating $100 million a year in sales; enough to attract investment from prestigious private equity firm Berkshire Partners, which purchased a 40 percent stake in the company in 2006 for an estimated $250 million (including debt).

But sustaining that sort of growth proved impossible. About five years ago the executives running Citizens of Humanity’s denim portfolio — which includes Agolde and Goldsign — realised something had to change. “I do remember thinking, ‘Oh shit,’” recalls chief executive Amy Williams. “We were at this point where we needed to evolve.”

For Williams, evolving meant updating styles and washes to reflect a then-emerging consumer penchant for more rigid, classic Levi's 501-inspired silhouettes. But she also had to rethink the company's retail strategy. She started by reducing its dependence on department stores and focusing on partnerships with specialty retailers like Anthropologie and Club Monaco, which typically buy into fewer denim labels, instead. E-commerce — both direct and with wholesale partners like Shopbop and Revolve — was prioritised.

With many denim brands, there's less of an emphasis on creativity and more on quality and fit.

Additionally, Williams worked to further develop the other brands in the group, refining Agolde’s youth-driven aesthetic and establishing Goldsign as upscale street-style bait, sold on Net-a-Porter and worn by editors at every fashion week. Karen Phelps, the creative director behind those two sister brands, was promoted to oversee the entire group last year.

In the midst of the restructuring in 2015, sales hit a record low. But as Williams' changes began to take effect, the business began to turn a corner and, by 2017, it was generating $100 million year once again. Early last year, Berkshire and Dahan began looking for an exit. In October, Williams and a group of private investors bought out both parties for an undisclosed sum. Sales are expected to rise by a respectable 10 percent in 2018.

ADVERTISEMENT

Citizens of Humanity may be growing once again, but transcending the tyranny of cool that drives the premium denim market isn't easy. Here’s a playbook on how it can be done:

Illustration by Jan-Nico Meyer for BoF

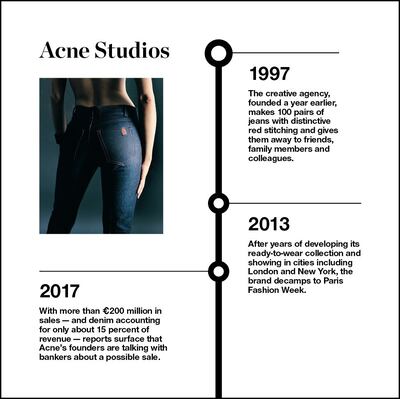

Become a ready-to-wear brand. Acne Studios was founded as a creative agency in 1996 and launched its first, limited-edition line of raw denim in 1997. But while the company was first and best known for its jeans, it quickly expanded into ready-to-wear, showing collections at Paris Fashion Week and beyond. By 2017, denim only accounted for about 15 percent of sales. The label currently generates more than €200 million a year, with founders Jonny Johansson and Mikael Schiller reportedly eying a sale.

It's the approach that has the best track record of success — Rag & Bone, too, managed to parlay a niche men's denim offering into a full-fledged ready-to-wear business that generates north of $300 million a year — but many brands have tried and failed, like J Brand. Part of it has to do with culture: a good percentage of premium denim labels are based in Los Angeles, with design studios connected to the factories. With many denim brands, there's less of an emphasis on creativity and more on quality and fit, which means it's difficult to establish a brand identity beyond jeans.

One label making a go of it is Frame, which was established in 2012 by Jens Grede and Erik Torstensson, co-founders of the Saturday Group, a multi-media fashion marketing agency. (Grede’s wife, Emma, co-founded Good American with Khloé Kardashian, another denim line pushing into new categories. In particular, bodysuits.) At Frame, womenswear sales are almost split between denim and other categories, which include apparel and accessories. (Its handbags, for instance, are sold exclusively in its own retail stores and e-commerce.) February 2018 marked the first month that the company shipped more ready-to-wear than jeans to stores.

“We didn’t start Frame to be a denim brand,” Grede says. “Denim happened to be the starting point. It’s also a global category that we thought had been misrepresented by a number of premium denim brands; they didn’t offer value for the consumer anymore.” Grede and Torstensson attacked the category by offering understated silhouettes (high, but-not-too high rises) and washes; their clothing, handbags and accessories like belts and socks are similarly subtle. “We have customers who buy four pairs of jeans a month from us,” Torstensson says. “But we see ourselves as a brand. Denim was just our first category.”

Illustration by Jan-Nico Meyer for BoF

Diversify by labels rather than categories. For brands whose core competency is making denim, the key may not be brand extension, but instead developing new brands aimed at different markets. While 15-to-20 percent of Citizens of Humanity's sales come from tops, "We're not looking to build a huge apparel business," Williams says. "I'm a little bit of a purist. What people come to us for is the best quality and most relevant denim." Instead, Citizens of Humanity has chosen to expand by further developing its other labels, which include denim-focused Agolde, Goldsign, fabric Brand & Co. and upscale basics line Getting Back to Square One.

ADVERTISEMENT

Focus on fit. There are certain brands that maintain a loyal following because of their unflinching fit. Paige Denim, founded in 2004 by Paige Adams-Geller — a former fit model for Citizens of Humanity and Seven for All Mankind — has carved a niche in the petites market. (In 2017, British private equity firm Lion Capital acquired a majority stake in the label from TSG Consumer Partners, although the terms of the deal were not disclosed.)

J Brand, too, has managed to retain some of its most loyal customers — in particular men, who tend to stick with one brand for a longer period of time — thanks to its minimalist approach. The brand was founded in 2004 by Jeffrey Rudes and Susie Crippen as an antidote to the elaborate back-pocket detailing that dominated the sales floor during the era. Acquired in 2012 by Fast Retailing, the owner of Uniqlo and Theory, J Brand was at one time pushing hard into ready-to-wear, even staging fashion week presentations. (Rudes exited in 2014 and Crippen, who exited in 2010 only to return in 2016 for a brief stint as creative director, is no longer with the company.)

But today, "a very small percentage" of the business — which is currently managed by Kazumi Yanai, son of Fast Retailing chairman and chief executive Tadashi Yanai — is ready-to-wear, although leather jeans continue to perform.

In 2018, J Brand underwent a rebranding, focusing its marketing efforts on best-selling styles, christening the newly formed permanent collection “Icons.” While Fast Retailing doesn’t break out J Brand’s revenues, e-commerce sales are up 30 percent year-over-year, according to the company.

Related Articles:

[ As Athleisure Cools, Denim Heats UpOpens in new window ]

The Coach owner’s results will provide another opportunity to stick up for its acquisition of rival Capri. And the Met Gala will do its best to ignore the TikTok ban and labour strife at Conde Nast.

The former CFDA president sat down with BoF founder and editor-in-chief Imran Amed to discuss his remarkable life and career and how big business has changed the fashion industry.

Luxury brands need a broader pricing architecture that delivers meaningful value for all customers, writes Imran Amed.

Brands from Valentino to Prada and start-ups like Pulco Studios are vying to cash in on the racket sport’s aspirational aesthetic and affluent fanbase.