The Business of Fashion

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

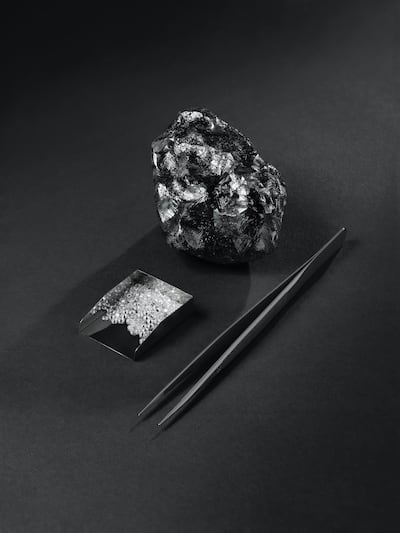

PARIS, France — Eliciting gasps in the dimly lit alcove on the top floor of the Louis Vuitton store on Place Vendôme, the unveiling of the 1,758-carat Sewelô diamond will probably go down as one of the best-executed publicity stunts in jewellery history.

Louis Vuitton, which hired former Tiffany & Co design director Francesca Amfitheatrof as its artistic director in 2018, earned dozens of digital headlines, and more than a few print features, for the purchase of the second-largest diamond ever found. (Its name means "rare find" in Setswana, a Bantu language spoken in Botswana.) It paid an undisclosed sum to own the avocado-sized diamond, which it plans to show to prospective clients around the world and cut to meet their desires.

1,758-carat Sewelô diamond | Source: Courtesy

The move may have startled many, but the rationale is simple. "Jewellery is one of the highest-growth categories we have, if not the highest," said Michael Burke, chief executive of Louis Vuitton. "I believe it's the biggest potential we have right now. Our clients are looking for unique diamonds, and the Sewelô diamond acquisition reinforces our legitimacy as a key high-jewellery player."

ADVERTISEMENT

Erwan Rambourg, an analyst at HSBC, agreed. “You have to think about the halo effect and how it puts the brand ever more forcefully on the jewellery map,” he said.

But the LVMH-owned megabrand is hardly alone in such gestures. The idea goes back to the 1930s, when Harry Winston promoted its 726-carat rough diamond, known as the Jonker, and has proliferated in recent years.

In 2016, Swiss watch and jewellery maker Chopard bought the 342-carat Queen of Kalahari, about the size of a madeleine cookie. In the same year, De Grisogono, another Swiss jeweller, bought the 813-carat Constellation for $63 million — marketing it as the most expensive diamond in the world. London-based Graff snapped the tennis ball-sized 1,109-carat Graff Lesedi La Rona for $53 million in 2017.

Jewellery houses are prepared to move mountains — or at least mine them — to grab a stone that will grab attention. The question, though, is whether buying these precious gems, with prices as outsized as their physical volume, is worth it.

Financially speaking, industry insiders agree that the answer is probably no. There are costs involved in analysing and cutting a rough stone — and no guarantee that all diamonds cut out of it will be of the same high quality.

And yet, the jewellery industry needs gems like religion needs miracles: for raising awareness, attracting clients and retaining old ones.

But finding gems isn’t as easy as it once was. As the number of brands playing in the high-jewellery arena grows, the supply of “exceptional” gemstones has, according to proprietors, diminished.

Van Cleef & Arpels brooch | Source: Courtesy

ADVERTISEMENT

"We have the impression that there are precious gemstones everywhere when, in fact, they are rarer than they were 30 years ago and more difficult to source," said Nicolas Bos, chief executive at Van Cleef & Arpels. His statements come ahead of the April opening of "Pierres Précieuses" at the Museum of Natural History in Paris, which will showcase the museum's rough precious minerals next to creations by the Richemont-owned jeweller.

Consumers, too, are chasing after such rarities. Despite disruptions in Western shopping habits and the rise of synthetics, the demand for natural diamond jewellery grew by 2.4 percent in 2018, totalling $76 billion, with rare red and green diamonds being the most sought-after varieties alongside mixed-colour ones — such as blueish-green or brownish orangey-pink — according to François Delage, chief executive of De Beers Jewellers.

Last summer, London jeweller David Morris almost instantly sold an earring set with a pair of Lightning Ridge Australian black opals totalling 31.40 carats, while Brazilian jeweller Ara Vartanian said he’s chased on social media by clients desperately looking for neon-blue Paraíba Tourmalines. “When a client asks for something in particular it gives me a mission,” said Chopard Co-President Caroline Scheufele. "[Sometimes] I will look for the purest form of the gemstone requested.”

Rare precious stones also hold their value. While the S&P 500 lost 38 percent of its value in 2008, the value of Argyle Pink diamonds increased by around 30 percent during the same period.

The bigger they are, the better they have performed, commanding a higher rate per carat. For instance, a 0.5-carat diamond, — about half the size of a mini Smarties — that is round-cut, colour D (which stands for the clearest possible colour on a scale from D to Z) and internally flawless would cost about $5,000, while a 5-carat one with the same characteristics would come close $500,000, or 10 times more per carat. Similar ratios apply to the other coloured gemstones, with rubies sometimes overtaking diamonds’ prices. For example, a 15.04-carat Burmese ruby formerly owned by Boghossian sold at Christie’s for $18 million in 2015.

Of course, when it comes to securing the best-and-biggest stones, those with the financial means, and the most prominent brand names, are favoured by traders. “I’m sorry for the others, but it is the big houses that get the best stones,” said Lucia Silvestri, creative director of the LVMH-owned Italian jeweller Bulgari.

Bulgari Cinemagia Necklace | Source: Shutterstock

Miners are also doing their best to ensure there are options. Adrian Banks, managing director of product and sales for the coloured-stone specialist Gemfields, said that the company invested $15 million in its Montepuez ruby mine in Mozambique to accelerate the sorting process. He also added that in the span of 10 years, Gemfields' emerald mine in Zambia tripled its output, while prices for the green rock increased more than six-fold over the same period.

ADVERTISEMENT

At the Letšeng mine in Lesotho in Southern Africa, mining company Gem Diamonds experiments with innovative ways, including more precise drilling, to identify diamonds within a kimberlite — the igneous rock containing diamonds — liberating them through a non-mechanical process. This is how the miner unearthed the 910 carat Lesotho Legend in 2018 and 11 diamonds greater than 100 carats — approximately the size of a macaron — in 2019.

But it is at the Karowe mine in Botswana, operated by Lucara Diamond Corp., where Sewelô diamond was extracted. A prize, to be sure, although Louis Vuitton’s Burke is aware that the Sewelô alone is not enough. “Size is not everything,” he said. “Creation, originality, audacity, craftsmanship, uniqueness, these are all main triggers for a high-jewellery purchase, something we already strive for.”

Disclosure: LVMH is part of a group of investors who, together, hold a minority interest in The Business of Fashion. All investors have signed shareholder's documentation guaranteeing BoF's complete editorial independence.

Related Articles:

[ What's Really Driving Success in the Fine Jewellery Market?Opens in new window ]

The Coach owner’s results will provide another opportunity to stick up for its acquisition of rival Capri. And the Met Gala will do its best to ignore the TikTok ban and labour strife at Conde Nast.

The former CFDA president sat down with BoF founder and editor-in-chief Imran Amed to discuss his remarkable life and career and how big business has changed the fashion industry.

Luxury brands need a broader pricing architecture that delivers meaningful value for all customers, writes Imran Amed.

Brands from Valentino to Prada and start-ups like Pulco Studios are vying to cash in on the racket sport’s aspirational aesthetic and affluent fanbase.