The Business of Fashion

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

A major reshuffle is underway in the luxury e-commerce market, as competitors scramble to seize a pandemic-driven boom in online sales. The pace of executive changes, public offerings, new joint ventures and M&A is picking up in a sector that’s provided the biggest — and at times only — growth opportunity for luxury this year.

Online luxury sales grew 50 percent this year, according to consultancy Bain, even as overall revenues declined by an average of 23 percent. But in the crowded sector, where popular items might be offered at the same price across a dozen sites only a click away, competition is fierce for both customers and talent.

And as investors have thrown even more cash behind the surging sector — most notably with Richemont, Alibaba and Artemis’ $1.15 billion investment in Farfetch — the pressure is on for e-commerce companies to spin the current momentum into profitable and sustainable growth. Where is the fast-changing market headed?

Executive shake-ups

ADVERTISEMENT

LVMH, YNAP and MatchesFashion have made a flurry of executive changes in recent days. On Monday, LVMH’s chief digital officer, Ian Rogers, announced in a blog post that he was stepping down from his role after 5 years. According to an internal announcement obtained by The Business of Fashion, LVMH is reshuffling its digital team, starting with the appointment of Michael David as group-wide “chief omnichannel officer,” plucked from the top ranks of Louis Vuitton, while former Sephora CEO Chris de Lapuente will add the struggling multi-brand e-commerce venture 24S to his portfolio of perfume and retail units.

At a group where brands are typically given a long leash to set their own strategies, the group also said it would “accelerate progress by converging towards common technology frameworks and solutions” under its group IT director, Franck Le Moal. Sharing technologies on the back-end could help the group’s smaller brands enhance their online service and do so more profitably.

Richemont also gave an update on its digital plans on Monday, finally announcing a successor to Federico Marchetti, the CEO of it’s Yoox Net-a-Porter division (Richemont looked in-house: appointing group digital distribution director Geoffroy Lefebvre, a former McKinsey consultant and graduate of France’s elite Ecole Polytechnique, to the role). The same day, Elizabeth von der Goltz, Net-a-Porter’s global buying director, announced she was leaving for smaller rival MatchesFashion as its new chief commercial officer.

Farfetch’s Alibaba-Richemont play

The executive shuffles come soon after Tmall operator Alibaba and Richemont each sank $500 million into YNAP’s rival Farfetch to fuel the platform’s growth in China, setting off a new arms race in the sector. The fact that the Pinault family (which controls Kering) also raised their stake in Farfetch helped reinforce the idea that the platform was poised to become the “Amazon of luxury” with its savvy alliances and operational heft — as well as pushing its valuation into territory where the company seemed too big to fail. Farfetch’s market capitalisation, up by a factor of more than 4 since the start of the year, is now $18.6 billion.

That means that if a long-predicted wave of consolidation comes for luxury e-tailers soon, Farfetch’s financial firepower alone should ensure it comes out on top. The pandemic has also served as a proof-of-concept for Farfetch’s marketplace approach — sourcing product from a broad network of luxury boutiques, as well as, increasingly, brand’s own stocks — which allowed the platform to keep fulfilling orders throughout coronavirus shutdowns when many retailers faltered.

Losses narrowed in the third quarter as sales jumped 71 percent, and founder José Neves is now forecasting that the company will post a positive EBITDA for the first time during the fourth quarter.

MyTheresa’s IPO plans

ADVERTISEMENT

Even as sales surge, many players remain stubbornly unprofitable, and analysts see the ultra-competitive sector as ripe for consolidation. But that doesn’t mean that being big is the only way to win, and some smaller challengers, such as Mytheresa, which filed paperwork for a proposed initial public offering with US regulators last week, are making the case to investors that they can still hack it in a crowded field.

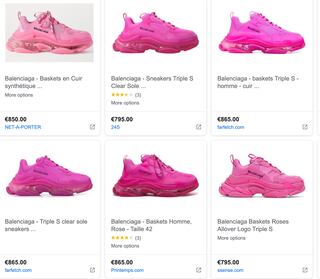

One of the sector’s biggest challenges is the high cost of acquiring clients amid steep competition. A quick web search for popular items like Balenciaga’s Triple S sneakers or the Loewe Puzzle bag illustrates the underlying challenge: the same high-end product can sometimes be found on more than a dozen multi-brand websites at roughly the same price. And after brands ramped up their own e-commerce efforts in recent years, luxury emporiums are left competing with their many rivals as well as the manufacturers themselves. The likes of Munich-based Mytheresa are betting on curation and personal service to set them apart.

“If you have a differentiated, creative offer, with a service that goes beyond the assortment, you can have organic traffic and a good rate of retention. Those are levers for profit,” Bain’s luxury goods analyst Claudia D’Arpizio said. “If you’re just a window, then you’re probably struggling to direct traffic to your site.”

As such, niche players who offer tight curation and top-level service for the lucky few, rather than shovelling cash into acquiring new clients (many of whom may lack the means to make regular purchases) are one cohort that may have a path to sustainable success.

Rather than becoming “Amazons,” they’d take on the role that was traditionally filled by luxury’s small, independent boutiques, with hands-on owners who had a laser focus on choosing the right products for their clients. MyTheresa is one retailer that’s taken that route, and has managed to generate consistent profit. The luxury e-tailer filed initial paperwork to go public last week, and is seeking a $1 to $1.5 billion valuation, according to market reports.

Brands reducing wholesale exposure

Meanwhile, several major luxury brands, including Gucci, Prada, Burberry and Celine, have been cutting out wholesalers in a bid to keep up with luxury’s biggest houses like Louis Vuitton and Chanel. Those two, along with Dior and Hermes, don’t sell their fashions through wholesalers at all, giving them unrivalled control over pricing and presentation.

That move away from wholesale could bode ill for luxury e-tailers’ ability to compete with the brand’s own websites long-term. Offering the chance to be part of an aspirational environment with prestigious curation is one way they can stay in the game. Another is to offer brands more control via online concessions: allowing them to choose which products to propose on a multi-brand site, as well as the price, instead of handing over their stocks to a third-party. Offering such an option has become increasingly important for Farfetch, on whose marketplace brands including Prada, Fendi, Gucci and Burberry all sell their products via concessions.

ADVERTISEMENT

Tech Goliaths in the wings

Of course, speculation of which fashion retailer can become the “Amazon of luxury” may end up being moot, as Amazon itself pushes into the luxury space. Its latest attempt, Luxury Portal, has been broadly snubbed by top brands. But Amazon may yet figure this out, or, as in the case of Whole Foods for groceries, purchase a company that already has.

In China, Alibaba’s Tmall already plays the role of a go-to destination for luxury fashion, along with everything from toaster ovens to shampoo. How much value Alibaba is willing to leave with partners like Farfetch and YNAP (who operate as joint ventures in the key market) remains to be seen.

One thing’s for sure, in luxury e-commerce, there’s plenty more change to come.

Related Articles:

Why Is Everyone Betting on Farfetch?

How to Beat Luxury’s Long, Slow Recovery, According to Bain

What the Farfetch-Alibaba-Richemont Mega-Deal Means for Luxury E-Commerce

The fashion giant has been working with advisers to study possibilities for the Marc Jacobs brand after being approached by suitors.

A runway show at corporate headquarters underscored how the brand’s nearly decade-long quest to elevate its image — and prices — is finally paying off.

Mining company Anglo American is considering offloading its storied diamond unit. It won’t be an easy sell.

The deal is expected to help tip the company into profit for the first time and has got some speculating whether Beckham may one day eclipse her husband in money-making potential.