The Business of Fashion

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

NEW YORK, United States — When Hood By Air designer Shayne Oliver needed to "make the kids gag" for his Autumn 2014 show, the former voguer called on a few friends from the city's ballroom scene, a Harlem-born subculture predominantly made up of people from the black and Latinx queer communities. During the finale, an army of toned, hair-whipping dancers stormed the runway to booming ballroom beats. Their duckwalks and gravity-defying dips shook the audience of industry insiders who had assembled at Pier 60 on Manhattan's West Side, starting the budding label on a rapid ascent to the very top of the fashion world.

Hood By Air, founded in 2006 by Oliver and Raul Lopez, unleashed a fierce new look on the fashion industry: an unruly collision of club-kid, gender play, pan-racial, artsy, hip-hop and high-fashion sensibilities. The brand was composed of two lines: a designer collection known as Hood By Air that was shown on the runway and sold at retailers like Barneys New York, and HBA, a line of 1990s-style logo T-shirts and deconstructed denim basics, sold at the likes of VFiles. Both helped birth "luxury streetwear" — the dominant force in fashion in the 2010s — years before it became a multi-billion-dollar business.

Hood By Air broke new ground with its disruptive shows and campaigns featuring an unapologetically diverse cast of queer and multi-ethnic street cast models long before inclusivity became a marketing strategy. Some were styled with weaves in their hair, stockings over their faces and crystal-encrusted metal mouth guards. The label elevated the street culture that shaped Oliver's sense of aesthetic while growing up in Brooklyn, with elements inspired by the likes of Helmut Lang, a combination reflected in the label's name.

Dancers voguing on the Hood By Air runway in 2014 | Source: Joe Kohen/Getty Images

ADVERTISEMENT

"I was always curious about the American Dream aspect of [fashion] and how it played into the actual creativity, which is what Hood By Air is about," Oliver told BoF at Sunshine Co, a restaurant near his home in the Prospect Heights, Brooklyn. "What is elitism, what is blue-collar — why are they so separate when they support each other? The elitism is in the idea."

At its peak, Hood By Air's shapes and style turned up on the mood boards of other designers; HBA in particular influenced the subversive, cut-and-paste logo T-shirts seen everywhere from Demna Gvasalia's Vetements to the concert 'merch' sold by Kanye West and Justin Bieber.

"In my eyes, Shayne Oliver invented luxury streetwear," said Beau Wollens, who was operations director at HBA from 2012 to 2015, and is now the chief operations officer at skater-inflected menswear label Noah. "There was something about what Shayne was doing that was so radical, you couldn't not look at it," added fashion consultant Julie Gilhart, a longtime champion of outsider design talent. "The way he showed and how he approached things, and the energy he had around him, really opened the door for so many."

Abloh, who in many ways followed in the footsteps of Hood By Air, collaborated with Oliver in 2013. “That moment when Hood By Air was breaking through was very timely and very inspirational,” said Abloh, describing Oliver as an innovator and artist à la Martin Margiela. “He ushered in this new era of [the] American designer, and I think that’s not often talked about.”

Oliver struck a chord with industry insiders, celebrities and consumers. In 2014, Hood By Air won a special award at the inaugural LVMH Prize and, a year later, a CFDA award for menswear. Fans and supporters included everyone from A$AP Rocky, who closed the label's Fall/Winter 2013 show, to Rihanna, who opened the 2016 MTV Video Music Awards in an all-pink HBA outfit. When "HBA Classics," a line of oversized graphic tees, dropped on the brand's website, they sold out quickly, and the category was a significant sales driver for the brand. And when they launched at stores like VFiles, K-pop stars flew in from South Korea just to buy them there, according to Zachary Ching, the label's former commercial director.

“Department stores were begging us to ship them anything we had. The brand was flying off the shelves,” said Wollens. “For an independent brand with no backers, business was good enough to support 10 to 11 full-time employees on payroll.” (HBA declined to share sales figures.)

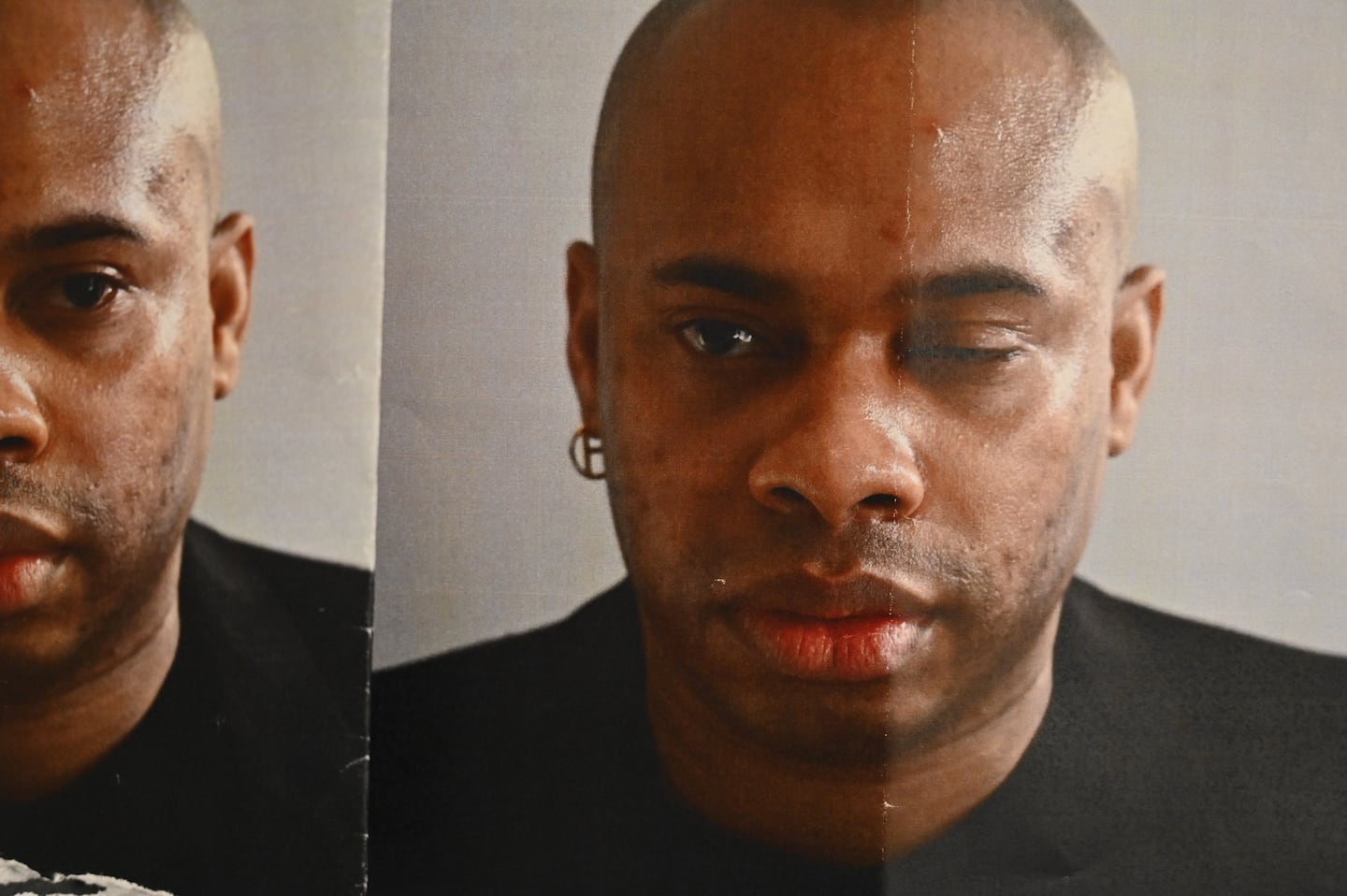

Shayne Oliver and Binx Walton at the 2015 CFDA Awards | Source: Jamie McCarthy/WireImage

Hood By Air's Spring 2016 show, staged at Paris Fashion Week, was a high point for the New York label, set to a remixed score by Arca and Total Freedom that included Rihanna’s American Oxygen, a politically charged song about immigrants and people of colour achieving their dreams in America.

ADVERTISEMENT

But only a year later, it was over. A few days ahead of what would have been Hood By Air’s second Paris show, the brand cancelled the event. Two months later, in April 2017, HBA went on indefinite hiatus.

The three years since the label went on pause have been difficult for Oliver, who parted ways with business partner Leilah Weinraub and took up a series of consulting projects. “It was horrible. I had to go through a moment where I was like: is this self-inflicted?” said Oliver. “The industry does drive you insane,” he adds. “And being eccentric is tiresome.”

The self-described “show queen” has learned some hard lessons from the rapid rise of HBA. Now, he has reunited with original HBA collaborators Ian Isiah and Akeem Smith, linked with a new business partner and is carefully and quietly preparing for a return to fashion on his own terms.

“This is going to be full drama,” he said. “I'm not seeing the heat right now. That's what makes me want to come back. Because I want to put some heat out here.”

What Happened to Hood By Air?

Many factors contributed to the downfall of the label: some of them were self-inflicted while others reflect failures in the American fashion system.

Although the designer was the face of the brand, HBA was powered by a boisterous behind-the-scenes collective. Many came from New York’s downtown creative community and, in particular, the underground GHE20G0TH1K parties launched by DJ and producer Venus X, with whom Oliver DJ’ed. Most were young and inexperienced when it came to running a business, and HBA lacked legal and operational structure when it was first formed, making things challenging when the label gained early traction. “For many, it was their first job. It was Shayne’s first job and first time managing money as well,” said Ching.

Oliver acknowledges that internal dysfunction at HBA contributed to the label's troubles. According to the designer, the collective was full of strong personalities, and managing the business became complicated as people jockeyed for position. New Guards Group, the Italian platform behind some of luxury streetwear's most-hyped brands, including Off-White, backed Hood By Air in 2016 but the relationship lasted only a year before dissolving.

ADVERTISEMENT

“The right foundation on our end wasn't in place to move the conversation forward,” said Oliver. “There were a lot of unanswered questions of how people were going to be involved. I was going to be taken care of, and the design team was going to be taken care of. But how was everyone else going to be taken care of? It had to do with egos.” New Guards Group did not respond to a request for comment.

Oliver developed a reputation for being difficult. “People think they can’t tame me and I have this very rebellious attitude because I challenge things, but I'm not sitting here rioting,” he said. “That was a point of, ‘Oh, well, he lives the lifestyle. Maybe we can’t tame that and bring that in.’”

But Oliver also didn’t fit the traditional fashion designer mold: he was black, queer, opinionated and had no formal training. And he believes America’s fashion system is also to blame for the challenges he faced with its failure to adequately support outsider talent with new ideas, paying them lip service with awards but ultimately preferring “safe” designers with traditional backgrounds and a low appetite for creative risks.

"[Don't] just throw them a prize and say, 'Oh, we did our duty,' and then put them in touch with CEOs that don't even want to have conversations with them," he said, critiquing initiatives like the CFDA/Vogue Fashion Fund. "Here, there is such a divide between the corporate side and the [creative] side" of the industry. "In Europe, the top editor will be at Craig Green's first show, but we have to wait four years to get that reaction. This is why we don't have stars."

Oliver also felt misunderstood by American retailers like Barneys New York, which picked up HBA, but put his collections on the contemporary floor alongside brands that sold at a lower price point and didn't present runway collections. "The systems you are trying to interact with in new ways are so defensive," he said.

“Maybe [Oliver] wasn't ready for the system that existed on the platform he was playing on, and maybe the platform wasn't really ready to support him,” said Gilhart.

“His story highlights how difficult it is to launch a business as an independent,” said Abloh, noting that many of the streetwear brands launched at the time were ultimately shuttered. “Hood By Air made it further than brands before it. Not many of those brands had considered showing at New York Fashion Week.” Abloh also thinks HBA’s collective structure was ahead of its time. “Business-wise, that infrastructure, had it been launched today, would have been easier and shorter conversations for him to have [with potential partners].”

Hood By Air runway in 2016 | Source: Kate Warren for The Washington Post via Getty Images

Post-HBA, Oliver was hired to work on a number of new projects, but nothing that would become a permanent new home for the designer. When he was drafted as "designer in residence" at Helmut Lang as part of a strategy to re-energise the storied but deflated brand with a series of capsule collections designed by guest creatives, he was excited to put his spin on the urban look pioneered by a designer that had inspired some of his own work, hoping the project would become more than a one-off. But the gig lasted only a season. "It was a little heart wrenching because… slowly but surely it became a thing where we realised that a continuation wasn't going to happen in any shape or form." A representative for Helmut Lang declined to comment.

Oliver continued to create capsule collections for brands looking for fresh energy — including Longchamp, Diesel and Colmar — which helped the designer recover financially and emotionally from HBA. Meanwhile, designers like Abloh and Gvasalia became the leaders of the luxury streetwear movement, landing the top jobs at Louis Vuitton and Balenciaga. Abloh's appointment marked a milestone for black designers, who have rarely helmed top fashion houses. But Oliver isn't satisfied: "Has it been established that black people come up with the ideas first? And that they are innovators? I don't think that we have gotten there yet."

Plotting Hood By Air’s Return

In January 2019, Oliver moved back to New York after two years of living and working in London, Paris and Milan. He has since reunited with original HBA collaborators stylist Akeem Smith and musician Ian Isiah and plans to relaunch HBA with a new business partner in the near future. But Oliver is keeping details about the venture and his strategy close to his chest.

“I always seemed like I was having fun, but I really wasn’t; I was trying hard to be taken seriously,” he said. “Now I'm actually wanting to have fun and push the luxury aspect of what I’m doing.”

In many ways, 2020 is an ideal time for Oliver to make his return to fashion: the internet has weakened the industry’s traditional gatekeepers while offering pathways for reaching fans directly. What’s more, the media, retailers and end consumers are all looking for black and queer designers as American society comes to terms with its deep-rooted prejudices and the market embraces outsider talents from marginalised communities as "cool." Luxury streetwear, too, is looking for fresh energy. But perhaps most importantly, Oliver has matured.

“How much was done in that span of time really, it’s kind of crazy,” the designer said. “I didn't understand how cool it really was. I just knew it felt organic and good … The new projects speak towards learning from that.”

Whatever Oliver does next, fashion will be watching. “People may have referenced [my collections], but I know what I was really thinking about, so I have that piece in my head,” he added. “I can now move forward with it.”

Related Articles:

[ The Image-Masters Behind Hood By AirOpens in new window ]

As the German sportswear giant taps surging demand for its Samba and Gazelle sneakers, it’s also taking steps to spread its bets ahead of peak interest.

A profitable, multi-trillion dollar fashion industry populated with brands that generate minimal economic and environmental waste is within our reach, argues Lawrence Lenihan.

RFID technology has made self-checkout far more efficient than traditional scanning kiosks at retailers like Zara and Uniqlo, but the industry at large hesitates to fully embrace the innovation over concerns of theft and customer engagement.

The company has continued to struggle with growing “at scale” and issued a warning in February that revenue may not start increasing again until the fourth quarter.