The Business of Fashion

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

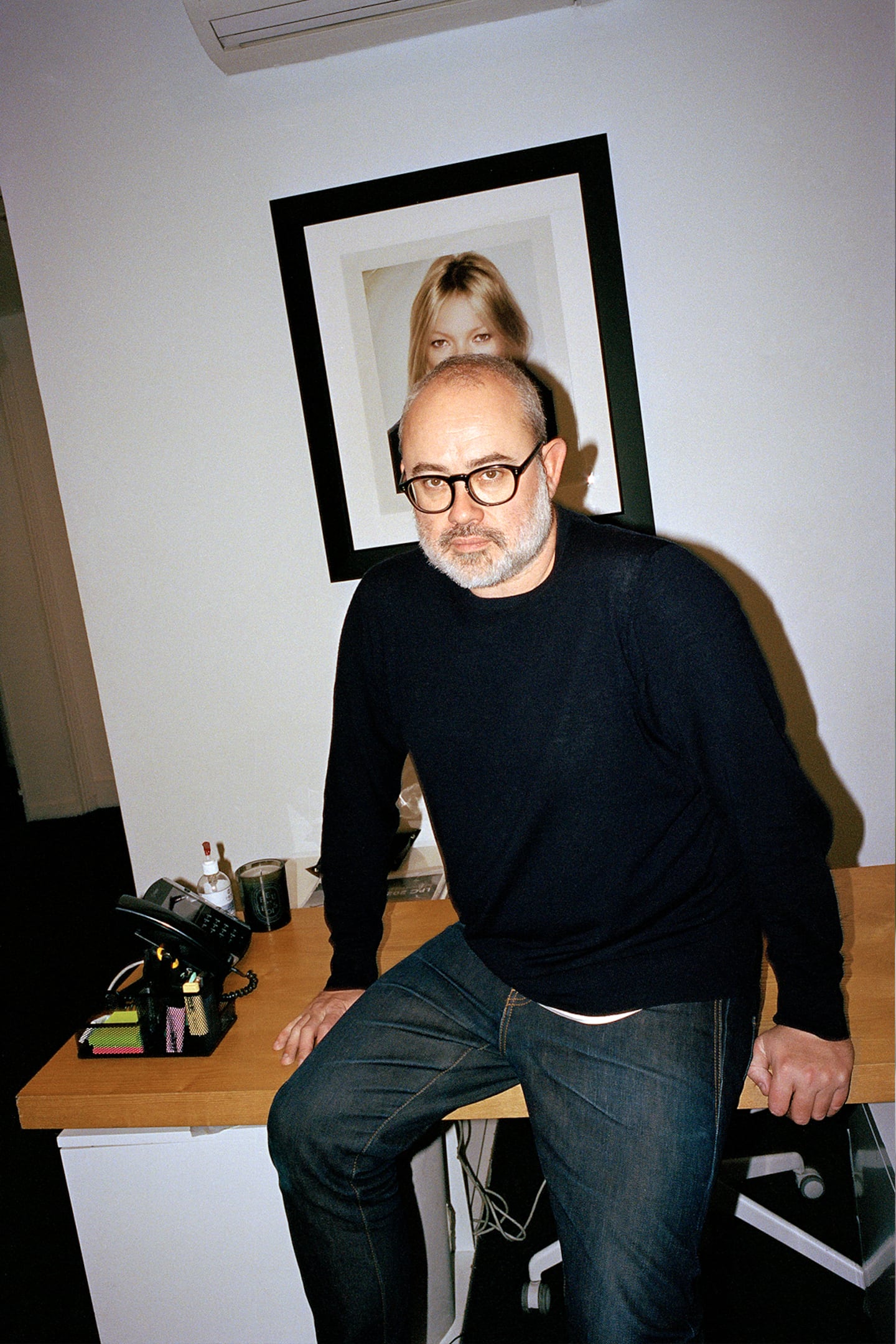

PARIS — It’s Monday, February 26, the start of Paris Fashion Week, and the public relations kingpin Lucien Pagès begins his day with a walkthrough of the space for Saint Laurent’s show, happening the following evening. He returns to his office to finalise the seating plan for the shows of clients like Schiaparelli, Sacai, Courrèges, Carven and Rabanne before a planning lunch with the organisers of the next Vogue World event. Then he has two shows by new designers, Marie Adam-Leenaerdt (a finalist for this year’s LVMH Prize) and CFCL, a Japanese disciple of Issey Miyake, before he ends his day at his friend Sarah Andelman’s launch of her new project, Mise En Page, at the department store Bon Marché. Over the course of the next nine days, Pagès will manage 25 runway shows, 11 presentations and re-sees, and nine dinners and cocktail parties for his clients. The list doesn’t include afterparties — of which there will be many — because he draws the line at late late nights.

His clients could scarcely begrudge him his bed rest. “I feel Lucien is my guardian,” says Schiaparelli designer Daniel Roseberry. “I call him the Prince of Paris because everywhere we go, he is so loved and respected. He also has absolutely no ego.” Saint Laurent designer Anthony Vaccarello goes a step further. “I think he is the best right now because he combines the knowledge and culture of the past, which we’re missing in fashion, and the codes of today. For me, that’s the mark of the great.”

“It’s a service,” is Pagès’s blunt rejoinder. “And I like to be in service.” At the same time, he acknowledges he has become the individual who most embodies ‘the fashion PR’ in the eyes of the industry. “Because I’m probably the most exposed as a person.” But the process by which the man who weaves stories for his clients has become a story himself was a deliberate move on his part.

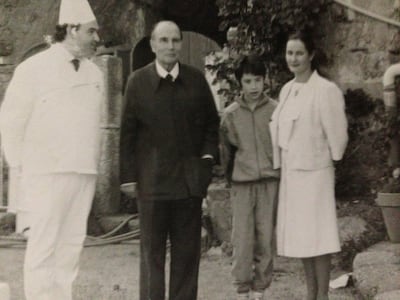

Pagès wants to prove what’s possible in life for people like him, he says. No child of privilege, he grew up far from Paris in Vialas, a small town in the remote, mountainous Cévennes in the southwest of France. The region has traditionally been a magnet for bohemians and non-conformists. His parents Patrick and Christiane ran a hotel with a Michelin-starred restaurant. In May 1987, French president François Mitterand helicoptered in from Paris for lunch. There was, fortuitously, a journalist in the restaurant at the same time. He photographed the Pagès family with Mitterrand. Lucien refused to change for the commemorative snap. “But retrospectively, I could say that press changed my life, because after we were on the front page of the local paper, we became more established, more respected. My father became a kind of legend.”

ADVERTISEMENT

There’s a curious psychology attached to hotels, especially when you live in them. “I realised recently we never had a family house,” Pagès muses. “We were always living with strangers, the clients, the staff. We’d eat lunch with the staff every day, 20 or so of them. My father and mother had a room, I had a room. Because it was in the mountains, we closed during the winter and I would take another more fancy room. It was totally like “The Shining.” I’d be running down the corridor because I was scared to go to my room. The corridor was red as well. But growing up in a hotel opens you to people. Even though I was shy, I was not that shy because my house was full of strangers, and also my parents served people all their lives. And now I’m serving people too.”

Patrick had always wanted to be a photographer. He was obliged to take over the family business when his mother died young. And he was equally obliged to make it fabulous, hence the Michelin star.

“Some chefs still know my dad, but he was more important to the wine industry because he created an association of sommeliers, and all his friends became the best sommeliers of the world. We had an amazing wine cellar.” But running a hotel in a remote French village was a curse for Pagès père. He travelled constantly, taught French cooking in Japan, and opened the first wine bar in Moscow. And he had a lot of famous friends, singers, writers, even Willy Brandt, the chancellor of West Germany. “How do you make that transition?” Pagès wonders about his father. “What drives you? I would not have been what I am without his ambition because he was a kind of case study of how you create yourself.”

But in those days Patrick was perplexed by his son. The solution to his skinny, long-haired only child’s perceived effeminacy was judo lessons, once a week for three years, from age eight to 11. And all the while, Lucien was increasingly, mystifyingly drawn to fashion. It wasn’t Christiane’s doing. She had no interest in it at all. But he’d be buying Vogue, Madame Figaro and Marie Claire Bis at the local newsagent, or he’d be transfixed by the nightly news in the hope that there might be a three or four minute update on what was happening at the haute couture shows. Saturday night was “Dynasty” night. Joan Collins was Lucien’s first crush, and also the first time he saw a gay character on TV. “I was living in the village of Vialas, dreaming to be on “Dynasty.” I remember someone asking me at the time whether I was studying for my driving test, and I told him, ‘No, I will have a Rolls-Royce and a driver because I saw that on “Dynasty.”’ And he said, ‘I can’t imagine you in a Rolls-Royce.’ Maybe that gave me the drive to end up in one. Though I’m still not there.” Pagès laughs now as he remembers his life as “the only gay in the village.” He’s mostly blocked whatever torment he suffered. “But when someone new arrived who was more gay than me, everything was on him and I was so relieved.”

1989 was a watershed year for teenage Lucien. The Italian Gianfranco Ferré was appointed at Dior and the scandalised French establishment was all over the TV. Karl Lagerfeld fired Inès de la Fressange as the face of Chanel for posing as Marianne, daughter of the French Revolution. More scandal. And a Saint Laurent show was deemed to be in bad taste. All Pagès could think of was Paris. “Christiane was always on my side. She knew I was gay. She knew I wanted to do fashion so she was facilitating things. I was talking to her first about how to prepare my father to accept things.” To accept, for instance, the fact that his son wanted to be Yves Saint Laurent.

When Pagès was 18, he saw an article in the weekly Nouvel Observateur which ranked all of France’s fashion schools. The hardest to get into was the Chambre Syndicale de la Couture, very select, very BCBG. Of course, that was the one he settled on. Family friends said it would never happen. That made him all the more adamant. Pagès arrived in Paris on a Sunday, and started school on the Monday. He was terrified. He imagined everyone would be in Chanel so he wore his most fashionable look: black turtleneck, red Cimarron jeans from Spain (very fashionable in the South) and Kenzo boots. When he got to school, no one was wearing Chanel.

By the time Pagès graduated from the Chambre Syndicale, he knew he could draw, he knew how to make a dress, but he also knew he could never be a fashion designer. “I was not able to do it, because I didn’t dare.” But the experience coloured his career, first and foremost with the instinctive understanding it gave him of the design process and the profound respect he has felt ever since for designers. When I ask what his favourite part of his job is, he takes a long time to answer. “I like it when we help people to have success, but my favourite thing is talking to the designer beforehand. Discovering the collection, what they are creating, what they want.” Designers are his true kindred spirits. “It’s the thing he respects in other people because he has it as well,” Daniel Roseberry observes. “He has a wildly rich education in the industry.”

His education also left him with an appetite for fashion’s inner sanctums. The Chambre Syndicale belonged to the Fédération de la Haute Couture et de la Mode, so students had access to fabulous internships. For three years, before every couture and ready-to-wear show, Pagès interned with Ferré at Dior, drifting dreamily in the slipstream of Naomi, Stella, Amber, Claudia and various Arnaults. But it was Saint Laurent he craved.

ADVERTISEMENT

He eventually wangled a meeting where he was offered a place in the atelier. He vehemently insisted that it was work directly with Monsieur Saint Laurent that he wanted, or nothing at all. Somehow, it worked, and Pagès found himself showing his portfolio to Anne-Marie Munoz, the house’s formidable studio director. He blanches as he remembers a disco collection that was more appropriate for Priscilla, Queen of the Desert than the Emperor of French fashion. Mme. Munoz felt the same way. “It’s everything we hate.” He was dismissed, only to be called back because Mme. Munoz had a change of heart. “She’s happy for you to stay because you’re discreet.”

Given that strange and shaky start, it’s small wonder that Pagès encountered some bitchy resistance. He was in his dream job but he was reminded that he didn’t belong. One day, in the grip of a panic attack, he locked himself in the bathroom and wouldn’t come out. Once again, Mme. Munoz came to the rescue, coaxing him out, giving him words of advice that still resonate with him to this day: “The road is long and the journey is full of traps.” His encounters with his idol Yves mostly involved Monsieur’s dog Moujik. The whole experience was inevitably fascinating for Pagès, but sad too. “That world doesn’t exist anymore. It showed me that fashion is changing, and we have to embrace it.”

That realisation led him straight to the heart of French fashion’s new wave. For five or so years he assisted stylist Marc Ascoli. He ended up helping out Ascoli’s girlfriend Martine Sitbon a lot, whose PR Michèle Montagne was old school in the sense that celebrity endorsements hadn’t crossed her radar. Which is how Pagès happened to intercept a fax from stylist Jessica Paster asking for some looks for her client Cate Blanchett. On his own initiative, he packed off a selection of dresses, one of which ended up on Blanchett and in Vogue. This first step into fashion PR was hardly Pagès’s Eve Harrington-like takedown of Michèle Montagne. “I wasn’t consciously building a network. I was a really good assistant, very dedicated. I never said, ‘Oh, I’ll be a PR.’ At the same time, I was in my late 20s, scared of where I would end up, and my friend Vincent Darré, who was at Ungaro, told me he was sure I would be a great PR, because I reminded him of Isabella Capece at Louis Vuitton. You know when someone turns a light on for you? I thought, ‘I should do PR.’”

At the time, he knew nothing of publicists like Karla Otto, or KCD in New York. The rest of Parisian PR was as old school as Michèle Montagne. So Pagès’s first client — the American menswear designer Adam Kimmel — was an unwitting declaration of intent. “I started working with Lucien in 2005 and he made all the difference in how a young American menswear brand could find an audience in Europe,” says Kimmel. They met through the stylist Aleksandra Woroniecka who knew his brother, the photographer Alexei Hay. “It took a bit of time,” Pagès recalls. “I helped him to do a presentation in Paris. I brought my friends. And then we decided to open the office together. He was smart. He told me, ‘If I show in Paris as an American designer, I want the French to love me. I need you as a kind of ambassador.’ So that was my mission, to make him the American that the French love.” Clearly it worked. Jonathan Anderson saw the now-legendary presentation that Kimmel did with the artist George Condo in Paris. “You just have to do one thing right. It was everything you would want in a show. I didn’t know where Adam Kimmel was from but he seemed so embedded in French culture, I instantly wanted to know who did the press for him,” says Anderson. “I brought Lucien on the minute I started work at Loewe. He was able to connect me with the French environment, which can be hard when you’re not from France. He’s good at showing you what the nuances are.”

“When we were together, we never felt like we were working,” Kimmel remembers. “And the worst stresses that would come, he would turn into a challenge that seemed to amuse him. He had the perfect mix of humility and ballsiness, as well as kindness and sarcasm… and always with elegance and an amazing sense of humour.” The Pagès agency was, at this point, himself and an intern. Through his friends André and Olympia Le-Tan, he learned of a Japanese designer named Chitose Abe. Well-known in Japan but nowhere else, she was keen to grow. On a press trip to Tokyo for Kimmel, Pagès saw a presentation for her label Sacai. He was captivated. Now he had a menswear designer and a womenswear designer on his client list. “People had never heard of Sacai, but everybody was laughing because Ça caille is slang for ‘It’s freezing’ in French. We grew together, which is something we share. I cherish our relationship for that, because it’s totally linked to my story.”

One of the first big events that Pagès worked on was the 2010 launch of M/M Mink, a collaboration between Swedish fragrance brand Byredo and the Parisian design agency M/M. Mathias Augustyniak and Michael Amzalag were friends from his days with Marc Ascoli. Byredo signed up. “Ben Gorham was the first person who trusted me for beauty, so he opened that door for me, like Sacai opened the door for womenswear.”

You can see a pattern emerging. Friends. Friends of friends. Adventurous young brands. I think of the extraordinary Jacquemus presentation during the pandemic, when 100 people convened in a wheat field outside Paris for the first fashion show in ages. It was a testament not just to the young designer’s vision, but also to his PR’s commitment to helping him realise that vision.

“I think that’s still my reputation,” Pagès says. “It’s something that we preserved. We are working for the big companies — LVMH, Kering, Richemont — but I still want that we are seen as this place for talent, because I think it’s part of what we do well.” The young guns join a long list, around 100 clients in all. Beauty alone is probably 25 accounts.

ADVERTISEMENT

As with any art gallery or agency, the client list is the key to success. “I knew that since day one,” Pagès agrees, “and that’s why I say money was never my motivation. I knew that the client list was the curation and I knew that the curation was a key to the business.” But you’ll often hear artists complaining that someone else is getting all the attention from their gallerist. Has that ever happened for Pagès? “No, because I have to be fair. There will always be frustration. It’s normal, it’s human.”

I envisage dozens of fragile egos needing a good massage and the exhausting degrees of commitment that must take. “You have to love every project,” Pagès counters. “You have to believe in it. If you believe in it, it can be enjoyable. Where it’s complicated is when you lose faith.” That happens regularly. “Yeah, I’m human,” he admits. “Sometimes there’s a project that doesn’t last long. They never take off. Also, I have experience. I see quickly when something will work or not. Three seasons, press people with experience know if there’s a chance. We know the traps.” Does someone of his repute think he can save careers with a little judicious PR? “If I arrive too late, no. Because it’s a combination of events. I can re-animate the interest, but if there is no follow-up with the commercial, with the structure…” The rest of his answer dangles unspoken over the void of oblivion.

“Sometimes PR’s can be overpowering in a weird way,” Jonathan Anderson says. “They want to hold the narrative. But Lucien is good at making a framework for the narrative to work within. A lot of the big PR companies are relics. Or they’ve collapsed. Lucien was on the cusp of change when that change was happening. He doesn’t do mean PR.” That’s a very good point. The meanness of traditional fashion publicists is one of the most caricatured facets of the industry. But Pagès agrees that the job has changed. “You have to behave differently. We are not allowed to scream at people. I was never tempted to be a monster. I don’t think it’s my nature. But if you are a toxic person, you will have trouble on social media.”

I feel I’ve been begging the critical question this whole time. What exactly is fashion PR? Pagès answers like someone who’s been asked it a thousand times. “For me, it’s really basic. It’s the link between a brand or designer and the media, the exterior world. I always give that definition because saying you’re doing consultancy and blah blah blah… I mean, I can be a consultant and sometimes I can be a therapist. It’s a mix. I’m there if people need my advice, but if they don’t need it I don’t give it. And sometimes I can be wrong. If you say the wrong thing at the wrong moment, you can fuck things up.”

“I understand why people don’t want to get too close to PR, because you can end up feeling manipulated,” he continues. “But I listen to journalists. I really learn a lot from them. Someone once told me about a PR who kept telling her she needed to see something because it was good, when it wasn’t. ‘She should just tell us, I need you to come.’ That stayed in my mind. Sometimes when you need people, you just have to tell them.” Pagès is always telling his team not to forget that public relations is about the relationship you create with your client or the media or celebrities or opinion leaders… whoever, just don’t forget the relationship. “Everybody matters in this industry,” he adds. “It’s a small world and creating this relationship is a key to success.”

In 2007, his father was diagnosed with cancer at the age of 57. During his four year fight, Pagès was back and forth to Vialas all the time. But when Patrick finally surrendered, Lucien was busy at Paris Fashion Week, supervising the launch of a Claudia Schiffer cashmere collection and the first show of new client Julien David. Father and son managed to iron out those childhood kinks before the end. “Dad didn’t know Adam Kimmel or Sacai, but he loved Claudia Schiffer,” Pagès says wryly. He was recently profiled in the newspaper Libération. His father’s friends called to tell him how proud Patrick would have been. No Rolls-Royce yet though.

DH-PR founder Daisy Hoppen, who is celebrating 10 years in business this year, built an agency that represents some of the most interesting creatives on the London Fashion Week calendar. Now, she’s evolving the business as she navigates a more challenging and competitive PR landscape.

With the news that The Independents is adding another firm, Ctzar, to its roster, BoF breaks down the factors driving consolidation in the space, and what it means for the industry.

The events production company known for staging some of fashion’s most impactful shows generated more than $100 million in 2019. The deal is a bet on the return of big physical fashion events, albeit with a digital dimension.

Tim Blanks is Editor-at-Large at The Business of Fashion. He is based in London and covers designers, fashion weeks and fashion’s creative class.

Join us for a BoF Professional Masterclass that explores the topic in our latest Case Study, “How to Create Cultural Moments on Any Budget.”

When done effectively, a cultural partnership can rightfully earn its own place in the zeitgeist. But it’s not so easy as just hiring a celebrity to star in an ad campaign; brands must choose a partner that makes sense, find the format that fits best and amplify that message to consumers.

Calvin Klein’s chief marketing officer Jonathan Bottomley speaks to Imran Amed about the strategy behind the brand’s buzzy Jeremy Allen White-fronted campaign.

Often left out of the picture in a youth-obsessed industry, selling to Gen-X and Baby Boomer shoppers is more important than ever as their economic power grows.