The Business of Fashion

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

This article is part of BoF’s special edition, Can Fashion Clean Up Its Act? Click here to learn more.

LONDON, United Kingdom — At the start of this year, Amy Hall was already facing an impossible mission. The vice president for social consciousness at Eileen Fisher was putting together the brand's 10-year plan to improve its environmental and social performance. The ambitious series of goals are intended to shift the company from a focus on reducing harm to a model that actually does good. "We don't have it all figured out yet," Hall said. "We created this not knowing how we were going to get there."

Then Covid-19 hit. Like the rest of the industry, Eileen Fisher has been left reeling by the sudden financial shock caused by lockdown measures implemented to flatten the growth curve of the contagion. The company, a certified B Corp, has had to furlough some employees and make painful cuts, but it has ensured all staff retain their health benefits. Sales have plummeted and the company is projecting in-store revenue to be down more than 40 percent for the rest of the year.

Eileen Fisher’s long-term environmental ambitions remain in place, but the reality is that resources once earmarked for sustainability initiatives have been diverted to simply keeping the lights on, at least for the time being. Already, a major project to establish a framework for effectively measuring and monitoring the company’s environmental impact has been delayed.

ADVERTISEMENT

“We really have to stay focused on what’s most essential for the health of the business,” Hall said. “It’s not a perfect world; we’re just trying to do the best we can.”

The tensions playing out at Eileen Fisher are reflected across the industry, as brands and retailers scramble to reconcile often costly commitments to operate more responsibly with the biggest global economic contraction since the Great Depression.

In Crisis, Clarity?

The coronavirus crisis has thrown into sharp relief many of the social and environmental issues that have long plagued the fashion industry, from its poor treatment of garment workers to the excessive waste and heavy pollution it produces. At the same time, it has created fresh challenges to incipient attempts to tackle them.

This crisis has started to bring to light some of the systemic problems in the industry... It's revealed just how fragile the industry is.

As governments shuttered malls and high streets in an effort to contain the virus, brands and retailers rushed to cancel production orders, in many cases refusing to pay for goods that had already been produced and asking for steep discounts to take delivery of products already in transit. The decisions have had devastating consequences down the supply chain, threatening the livelihood of some of the industry's most vulnerable workers. On the environmental side, retailers are scrambling to figure out what to do with growing mounds of excess inventory, a stark reminder of the sheer volume of product, and waste, the industry generates. Most of this stock will likely be sold at steep discounts. Some may end up in landfills or incinerated.

“This crisis has started to bring to light some of the systemic problems in the industry,” said Carry Somers, co-founder and global operations director at nonprofit Fashion Revolution. “It’s revealed just how fragile the industry is.”

The situation has amplified conversations that have been gaining traction for years, as political, cultural and financial shifts forced the fashion sector to grapple with what it means to be a responsible business. Broad global trends including mounting wealth and income inequality and the rise of political populism have buoyed efforts to address what some see as the excesses of capitalism. The question of what makes a responsible business has moved from a niche focus for corporate social responsibility teams and sustainability experts to a central issue for chief executives to address. Meanwhile, the climate crisis has become an increasingly serious issue for consumers, politicians and investors. An alarming upsurge in natural disasters has served as a consistent reminder that this is as much about risk mitigation as it is "doing the right thing."

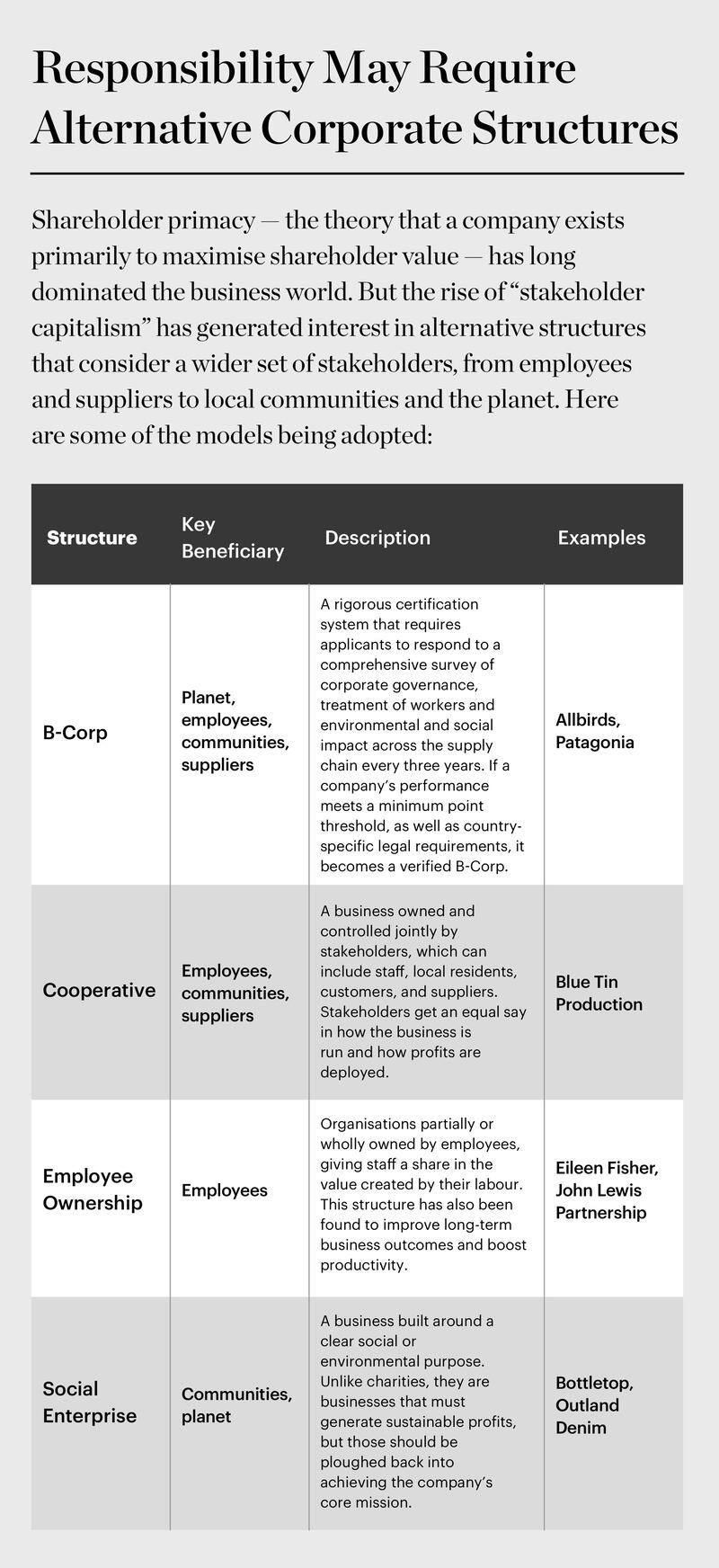

As a result, the doctrine of shareholder primacy that has governed business practices for decades has been called into question. In its place, many are lobbying for a new form of “stakeholder capitalism” that requires companies to consider the interests of employees, suppliers, local communities and the planet, alongside making money for investors.

ADVERTISEMENT

This new, more friendly version of capitalism puts purpose at the heart of business. Proponents argue any hit to profitability in the near-term will pay dividends in the future by ensuring companies' long-term license to operate in an increasingly "woke" socio-political climate and by embedding resilience against systemic shocks into corporate strategies. Those arguments are increasingly compelling in an ever more interconnected and uncertain global business context.

The question of what makes a responsible business has moved from a niche focus for corporate social responsibility teams and sustainability experts to a central issue for chief executives to address.

“We see the kids protesting in the streets,” said Stefan Seidel, chair of the UN Fashion Industry Charter for Climate Action’s steering committee and head of corporate sustainability at Puma, referring to the school strikes boosted by teenage climate activist Greta Thunberg that swept the globe over the last year. “That of course has shown that there’s a great public interest, specifically from that generation. And as we are targeting that younger generation as well — these are our customers, these are our future employees — that has made an impact.”

These concerns are likely to become only more compelling as the immediate financial panic surrounding the coronavirus outbreak subsides. According to BoF and McKinsey & Company's Coronavirus Update to The State of Fashion 2020, "the pandemic will bring values around sustainability into sharp focus, intensifying discussions and further polarising views around materialism, over-consumption and irresponsible business practices."

The UN has urged governments to use the huge stimulus packages that will be needed to jumpstart economies as they reopen to invest in green transitions and sustainable growth. Some investors, too, are doubling down on commitments to businesses that can show they are balancing profit and purpose.

“The pandemic we’re experiencing now highlights the fragility of the globalised world and the value of sustainable portfolios,” Larry Fink, chief executive of the world’s largest asset manager Blackrock wrote in a letter to shareholders at the end of March. “We’ve seen sustainable portfolios deliver stronger performance than traditional portfolios during this period.”

Already, brands are facing intense scrutiny for the way they are behaving during the crisis. Companies that cancelled orders that had already been produced or shipped have been called out publicly by campaign groups demanding that they pay their suppliers. Direct-to-consumer label Everlane has been lambasted on social media by US Senator Bernie Sanders over allegations of union busting that the brand vigorously denies. Such issues are only likely to gain traction as consumers grapple with the reality of mass unemployment caused by the pandemic’s devastating impact on the global economy.

“It’s hard to tell at this stage how much brands’ bad behaviour is going to impact customer trust, but we certainly saw after Rana Plaza some complete PR disasters,” said Fashion Revolution’s Somers, referring to the 2013 factory collapse that killed more than 1,000 garment workers in Bangladesh. “At a time when customers have limited money and are maybe buying more carefully, if those brands and retailers haven’t managed to keep customers’ trust through this, I think they should be quite worried.”

The doctrine of shareholder primacy that has governed business practices for decades, has been called into question. In its place, many are lobbying for a new form of 'stakeholder capitalism.'

And yet, on the flipside, the crisis has turbocharged aggressive lobbying by industries like automobiles and aviation in need of bailouts. UN climate talks due to take place in Glasgow at the end of this year have been postponed to 2021, delaying the next round of global commitments. Financial crises have historically weakened labour movements. Far from doubling down on socially and environmentally progressive policies in the aftermath of the current turmoil, governments and companies may be tempted to pursue growth at any cost.

ADVERTISEMENT

“Unemployment is going to be at least the most since the Great Depression, so we are going to face some real financial issues,” said Joey Zwillinger, co-founder of eco-conscious footwear brand Allbirds. “One of my concerns is that things like climate change get set aside, and people focus purely on economic well-being at the detriment of society’s well-being.”

The retail sector is experiencing a bloodletting. Fashion stalwarts including J. Crew and Neiman Marcus have filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection. This year, revenues for the global fashion industry are expected to shrink by roughly 30 percent, according to the Coronavirus Update to The State of Fashion 2020. Millions of garment workers have already been laid off as factories were required to close for health reasons and order volumes shrivelled. Many fear they will never reopen. Fashion's biggest brands have cancelled dividends, slashed executive pay and warned of thousands of job losses.

The situation is complex and fast-moving. Under the circumstances, it may be tempting to dismiss efforts to reform business practices as blue-sky thinking, but doing so may leave fashion businesses ill-prepared for the future beyond the immediate crisis.

"In times of crisis, it's more and more important to show you can run a good business and at the same time protect people and the environment for the long run," said Kering's Head of Sustainability Marie-Claire Daveu. "Profit and purpose are not fighting."

What Does it Mean to be a Responsible Business Anyway?

At the heart of the movement towards more responsible business practices is the idea that a firm should not exist only to maximise the profit of its shareholders.

“This idea that we have to be responsible for the air and the water and the land should be integrated into every business's thinking,” said Eileen Fisher. “I really think the whole capitalism model has to change. It has to include the cost to the workers and the planet.”

If it sounds simple in concept, it is deeply nuanced and complex in practice. It is easy enough to challenge the notion of shareholder primacy. More challenging is “just defining what exactly ‘good’ looks like,” said Tyler Gillard, head of sector projects at the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development’s Centre for Responsible Business Conduct.

In times of crisis, it's more and more important to show you can run a good business and at the same time protect people and the environment for the long run... Profit and purpose are not fighting.

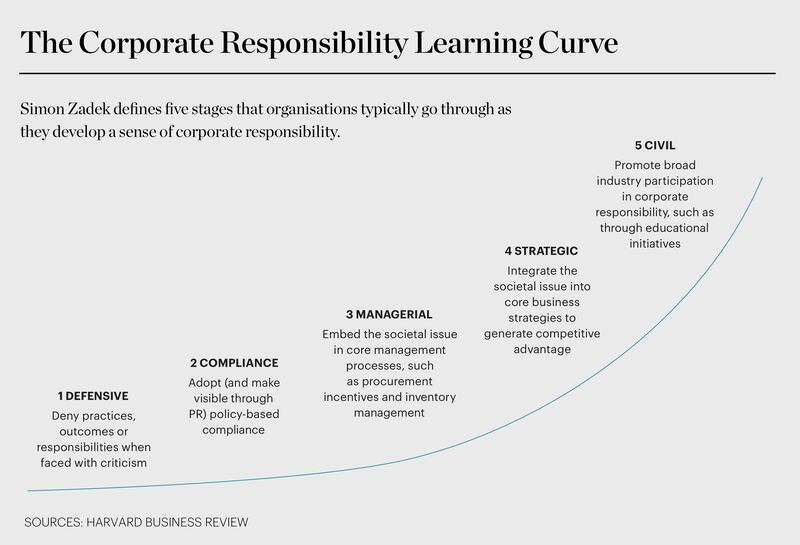

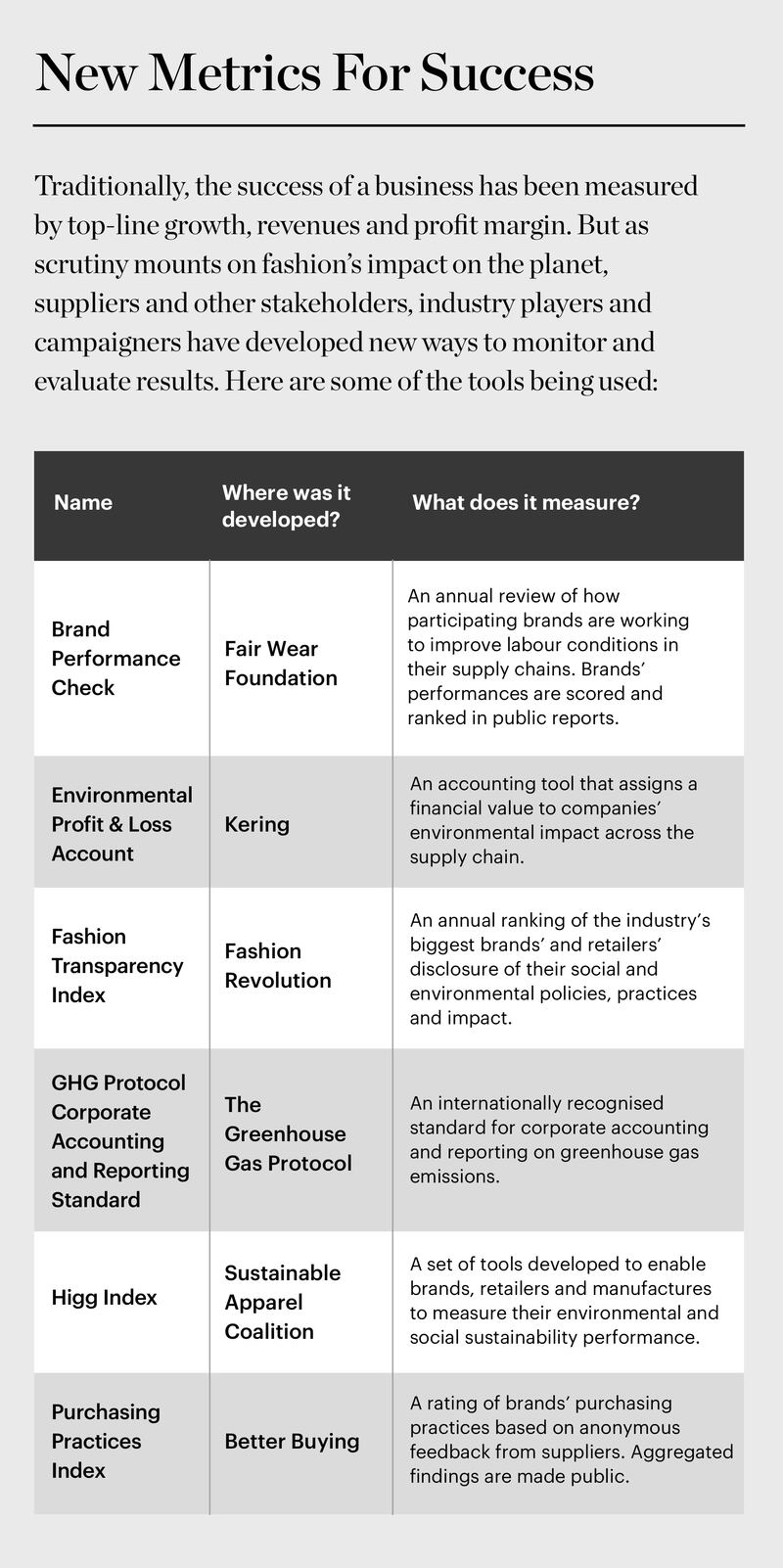

Responsible business practices are a moving target that evolve with technological innovations and cultural perceptions. Historically, they have often been limited to piecemeal corporate social responsibility initiatives that are not embedded into businesses’ overall strategies. While there are established metrics to measure a company’s financial performance, benchmarking environmental and social impact is less well-established and poorly regulated.

There are frameworks that exist. The OECD has put together due diligence guidelines for the apparel and footwear sector, designed to provide common processes and standards to prevent negative fallout from business operations. The UN has laid out ten principles of corporate sustainability in its global compact. Its seventeen sustainable development goals are intended to act as a blueprint for progress over the coming decade.

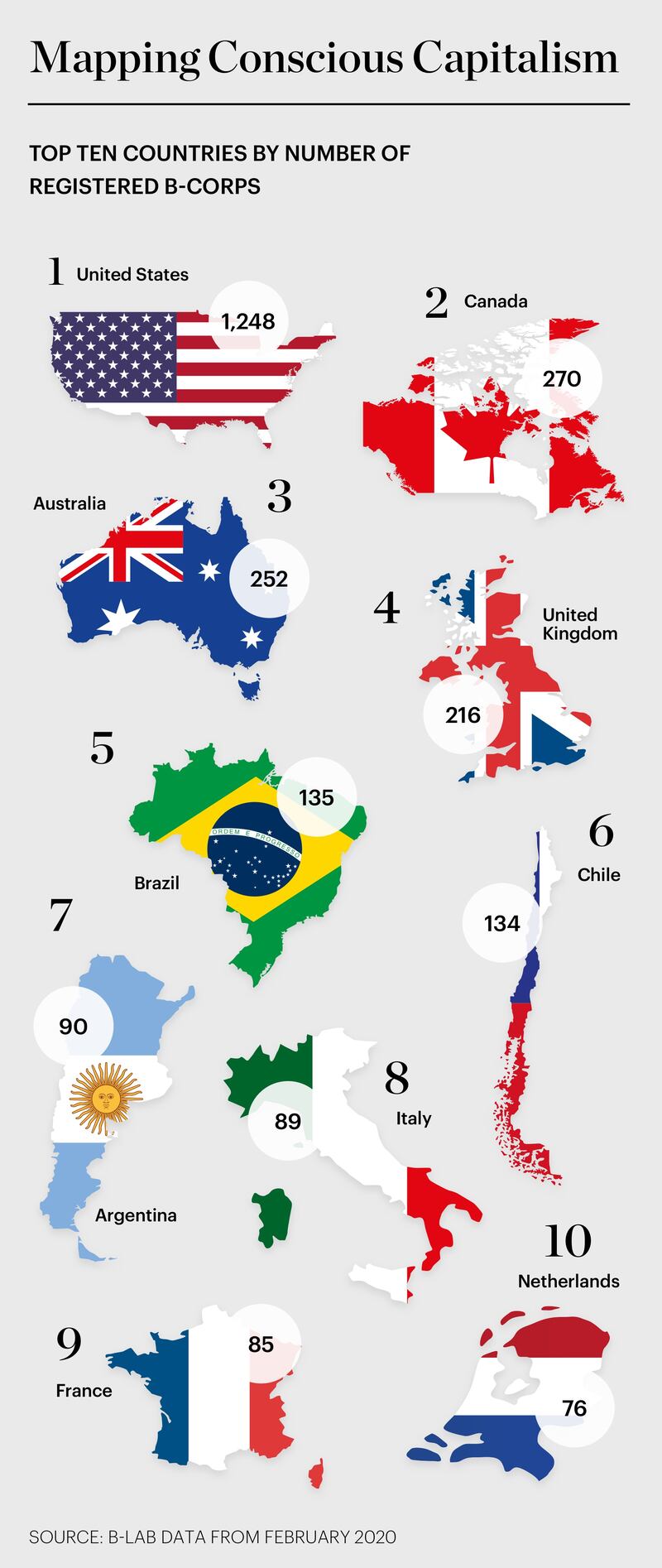

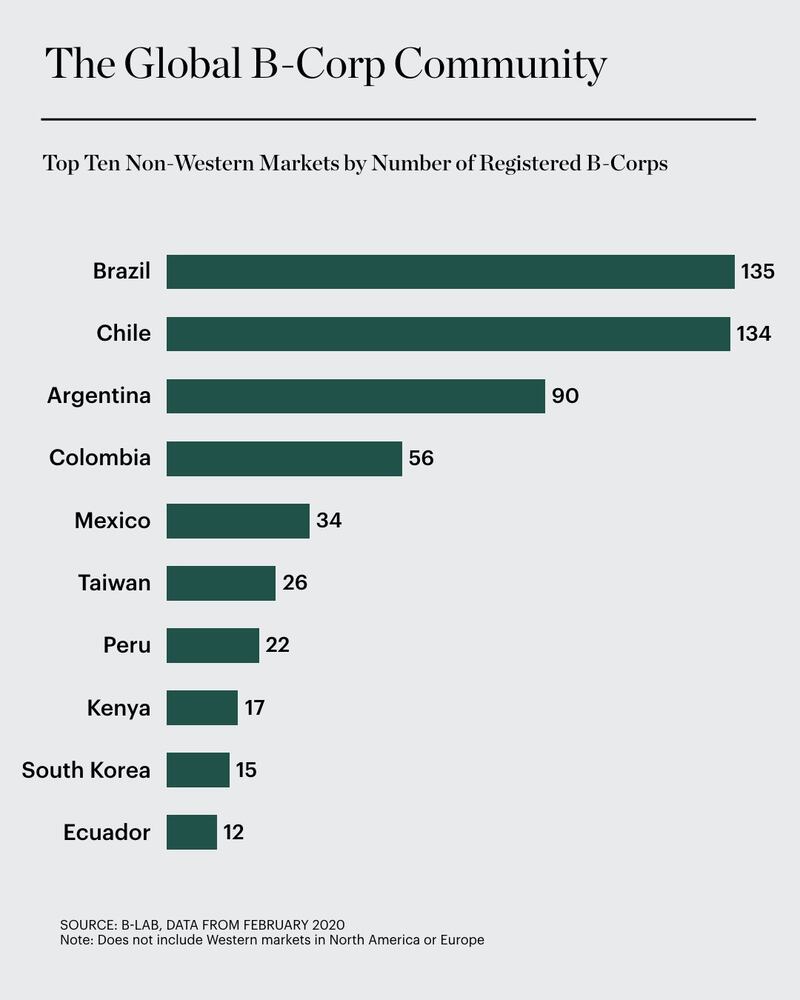

More than 3,000 companies are certified as “B Corporations,” which means independent monitors have verified they meet rigorous standards of environmental and social performance, transparency and accountability. Within the fashion world, Patagonia, Allbirds and Eileen Fisher are among the few that have gained the certification.

And yet, definitions of what it means to operate responsibly remain fuzzy, despite an avalanche of high-profile commitments over the last few years. The industry remains addicted to sales growth that sits uncomfortably alongside climate goals. Many companies continue to operate business as usual while touting "sustainable" collections or plans to eradicate virgin polyester, and doing little to address social issues within the supply chain.

“If you look at sustainability, it has an environmental dimension, an economic dimension and a social dimension,” said Puma’s Seidel. “It cannot be one or two topics only that you focus on.”

A Social Contract

At the start of this year, many industry watchers worried that low-impact, high-visibility environmental initiatives were overshadowing social concerns within the fashion industry, allowing businesses to shift focus from deep-seated structural problems to consumer-friendly, but relatively low-touch, climate initiatives, like take-back schemes for old clothing or limited and siloed shifts to vaguely defined “sustainable” materials.

Covid-19 has in some ways flipped the switch, laying bare inequities within fashion's supply chain that now leave millions of vulnerable garment workers at risk of destitution and disease. Despite the dire financial stress many companies are facing, they are also being held publicly accountable for the way their strategic decisions are affecting workers.

Beyond the immediate crisis, fashion has long struggled to operate in a manner that protects employees and the wider communities the industry touches. The problems are multidimensional and cover a broad network of stakeholders, including employees, consumers and the workers that support fashion’s supply chain. The challenges relate to diversity and inclusion, worker abuse and harassment, and fair wage levels.

Tackling these issues is no simple task. They can be hard to quantify, and even harder to address, but failing to do so can leave brands exposed to scandal, reputational damage and lost consumer confidence.

Consumer expectations are constantly evolving and have caught brands wrong-footed in the past. Gucci faced a public relations crisis last year after the company sold a jumper that many found offensive for its resemblance to blackface, a scandal that also exposed the lack of diversity within the company's executive ranks. The backlash against Burberry for the common practice of incinerating unsold goods prompted the company to become the first luxury brand to commit to abandoning the practice altogether.

Within the workplace, public scandals such as those around the treatment of models have illustrated the risks employees and contractors face when they speak up on issues of harassment, particularly in the fashion industry, where many work as freelancers dependent on relationships to continue to get work.

Those issues are amplified further down the supply chain where brands have less visibility into how operations are managed, and workers are often disempowered. For many companies in the industry, profitability depends on a competitive model rooted in low-cost manufacturing that has historically proved detrimental to workers.

“This was a sweatshop industry and it’s still operating as a sweatshop industry,” said Marissa Nuncio, director of the Garment Worker Centre, which campaigns for labour rights in Los Angeles apparel factories. “Even where there are really true ethical producers, there are folks that are greenwashing.”

In the face of the current crisis, it may be tempting for brands to shift focus away from costly initiatives to mitigate climate impact. But if the industry's immediate challenges are financial, its next crisis may well be environmental.

To be sure, for all its challenges, the industry has also been instrumental in lifting millions out of poverty and driving growth in economies like China, India and Bangladesh. And there are signs of progress, even amidst the current criticism, with some companies committing to continue to support their manufacturers and protect employees.

Even so, layoffs are already widespread, and jobs in the industry are likely to come under more pressure still in the coming months as lockdowns are extended and government support schemes are phased out.

Near-term, managing such decisions responsibly is fraught and important for reputation, particularly for companies that already promote ethical practices as part of their branding. Going forward, embedding responsible business practices into the industry will require deeper structural changes to fashion's sourcing and manufacturing models, which remain opaque and exploitative.

Clean Fashion

While Covid-19 has forced the industry to face head on some of its structural inequalities, in the face of the current crisis it may be tempting for brands to shift focus away from costly initiatives to mitigate climate impact. But if the industry’s immediate challenges are financial, its next crisis may well be environmental.

This year, the World Economic Forum’s annual Global Risks Report was dominated by the environment for the first time, following a year of floods and droughts that hammered home the business risks presented by climate change.

While the data on fashion's climate impact is famously poor, the industry undoubtedly has a hugely negative environmental impact. Fashion spews out carbon and toxic chemicals, while guzzling water and generating huge volumes of product, over 70 percent of which ends up in landfill or incinerated, according to the Ellen MacArthur Foundation. Last year, 114 billion items of clothing were sold globally, according to Euromonitor International. According to consultancy Quantis, the apparel and footwear industries are responsible for roughly 8 percent of the world's greenhouse gas emissions.

For anyone in doubt, the glut of inventory currently piling up in warehouses globally is a very visible reminder of the sheer excess in the sector, and the tension between growth ambitions and climate goals.

Underlying efforts to move to more responsible business practices is a central tension: the balance between purpose and profit.

“The fundamental models of the fashion world are being questioned and have been for a number of years,” said Elisa Niemtzow, vice president at nonprofit consultancy BSR.

To be compatible with global climate goals, the industry as a whole needs to drastically reduce its emissions and cut back the waste it generates. Companies need to put resources into understanding their supply chains down to the raw material level and into transitioning to less extractive modes of operating. Arms-length sourcing practices need to shift to a point where companies are supporting regenerative models of agriculture that sequester carbon and protect biodiversity. Brands need to find solutions to ensure old clothes don’t end up in landfill or incinerated, and find ways to continue to drive profitable growth while producing less.

“We need to stop thinking about just doing less harm, as we have all been trained to do,” said Eileen Fisher’s Hall. Instead, the industry needs to start thinking about framing corporate strategies around “the positive impact we’re having through our actions.” While Hall acknowledges the company’s ambitions may be slowed by the financial fallout from Covid-19, they remain firmly on the agenda.

Elsewhere, too, there are signs that companies are continuing to at least think about climate action. Despite the crisis, the Fashion Pact, an industry initiative pulled together by Kering Chief Executive François-Henri Pinault last year, is continuing to hold regular meetings of its operating committee, said Kering's Daveu. Even at the chief executive level, engagement remains strong, and new brands have also approached the group about joining since the crisis began, she added.

“They want to continue to act,” she said. While executives are focused on managing the current crisis, they are “also anticipating for the future.”

Sustainable Profits

Underlying efforts to move to more responsible business practices is a central tension: the balance between purpose and profit.

There’s a growing school of thought that the two are not incompatible: better paid, better cared for workers are more productive. Near-term investments in environmental improvements will pay dividends in the long term. Investors increasingly see such issues as risks companies need to manage to ensure long-term profitability. A growing school of research points to the resilience of companies that operate in this manner during economic shocks and even suggest strong environmental, social and corporate governance can help boost long-term returns.

But balancing those demands in a troubled retail climate is increasingly tricky and nuanced. Many businesses have been forced to make painful choices to lay off workers and cut back operations simply to survive.

Some fear that the crisis currently engulfing the industry could embed entrenched business practices even further, undoing recent progress as brands pull back from investments in climate-friendly practices and ratchet up pricing pressure on suppliers in a bid to return to profitability.

Driving change, particularly during times of great upheaval requires visionary leadership and courage.

Even before the current crisis hit, many brands were vague about how exactly they planned to transition to more responsible operating models and the spending plans they had put in place to get there.

But some see a rare opportunity for radical change. Times of crisis can provide a catalyst for new frames of thinking. The economic and human disaster unleashed by the current pandemic has laid bare weaknesses in the current system and may reshape the way investors and executives think about success, helping focus shift to long-term resilience. Truly operating in a responsible manner may require rethinking the industry’s growth-focused business model and redefining what success looks like.

“Profit is important, but is out-of-control growth the goal?” said Fisher. Her company was actually at its most profitable when it was half its current size.

How to Build a Responsible Business

Driving change, particularly during times of great upheaval, requires visionary leadership and courage. In the coming months executives will face extraordinary pressure to sustain their businesses and provide a clear strategy for recovery.

They have an opportunity to embed responsible operations into that strategy. Indeed, doing so may prove vital to remaining relevant to consumers coming out of this crisis and help prepare businesses for future shocks. But equally, such a recovery strategy may require sacrificing near-term gains and finding money for fresh investments at a time of great constraint.

A Question of Culture

The first step is a reset in corporate culture. Top executives need to shift their mindset away from a profit-first model. Resilient business strategies need to focus on a more holistic approach to success that takes into account positive impact on people and planet as well as financial gain.

“You need to integrate responsible business into your core business function,” said Seidel. “You can’t just have a small sustainability team.”

Companies should consider tying executive remuneration to delivery on environmental and social targets and putting in place mechanisms to ensure those goals are given adequate weight in strategic decision making.

At Allbirds, the company embeds a carbon price of $100 per ton into its model during product development, forcing its team to take into account the environmental cost of each decision.

“When you do that, you strip the emotion away and turn it into an objective decision about whether you’re putting more cost on society,” said Zwillinger. “So you err towards reducing your carbon impact.”

You need to integrate responsible business into your core business function... You can't just have a small sustainability team.

Kering’s well-established environmental profit and loss, or EP&L, account serves a similar purpose, placing a financial value on the company’s environmental impact.

Such initiatives need to trickle through to every aspect of the business. The creative team must be trained in circular design to minimise waste and allow garments to be more easily recycled, and buyers need to be given different incentives to ensure responsible sourcing. Such measures can have a substantial impact.

For instance, Eileen Fisher is anticipating a 25 percent reduction in its emissions from manufacturing and shipping by 2024, primarily through building more efficiency into product development, shipping by sea rather than air and creating a leaner product line to reduce inventory levels.

To be sure, cultural change is not easy and the industry has struggled to adapt in the past. But the current crisis may prove so disruptive that it enables radical shifts that would have taken years to embed previously. The disruption currently underway could help break down old models that sustain bad practices and clear out entrenched thinking.

“Even if it’s not a total revolution, at least you will have some change,” said Kering’s Daveu.

Breaking Fashion’s Black Box

For years, a major barrier to fixing many of the social and environmental issues within the fashion industry has been its opacity. Its sprawling and convoluted supply chains enable abuses and leave businesses ignorant of the extent of their impact.

That needs to change for any claims of responsible business practices to be credible. Companies need to be monitoring and measuring their social and environmental impact in the same way they do their financial performance in order to ensure accountability and progress.

According to the Fashion Transparency Index, an annual scorecard put together by nonprofit Fashion Revolution, the industry's average score remains at just 23 percent. The quality of the industry's disclosures, which remain largely voluntary and unregulated, has also come under fire. At the same time, brands are able to label their clothes as more sustainable with little information about what that actually means.

More rigorous disclosure isn't easy. Most brands have limited visibility into their supply chains and achieving greater transparency is a labour-intensive and expensive process. Environmental disclosure is an evolving art. The tools to assess the environmental impact of a product are imprecise and the data available to the fashion industry is notoriously bad.

Meanwhile, the tools to understand and monitor labour practices have also often proved to be inadequate in a world of distant and sprawling supply chains. Most companies rely on third-party audits to ensure codes of conduct are being upheld within their supply base, but these have frequently failed to identify and prevent abuses.

A report published last year by labour organisation the Clean Clothes Campaign identified fatal shortcomings in the existing corporate social auditing system, pointing to a host of deadly disasters in garment factories where violations had not been noted by well-established auditing firms.

Many agree common standards and tighter regulation are needed to drive change. At present, the lack of regulation means brands can largely disclose their environmental and social performance how they like and disclose nothing at all if they prefer.

“For many cases they are marking their own homework,” said Sarah Ditty, global policy director at Fashion Revolution.

Show Me the Money

Fixing such problems requires investment.

Within the fashion industry, materials that are grown and manufactured in a way that is less damaging to the planet are often more expensive. Technological innovations to enable the industry to move towards a more circular model require investment to develop and scale. Manufacturers need financial support to shift away from fossil fuels and towards renewables and energy-efficient technologies. Similarly, ensuring that wages are sufficient throughout the supply chain inevitably means spending more on salaries.

Climate change isn't going to delay while we sort out coronavirus... Brands should not be putting down wider responsibilities to climate change and labour.

Spending is a delicate subject, particularly at a time when companies are facing a precipitous drop in sales and extended cash crunch, but operating responsibly comes with a price.

“Climate change isn’t going to delay while we sort out coronavirus,” said Lucy Shea, group chief executive at sustainability consultancy Futerra. Brands “should not be putting down wider responsibilities to climate change and labour.”

Investment and financing was a challenge even before the current cash crunch. Outside of athletic brands like Nike and Adidas, the fashion industry has not historically put substantial resources into technological innovation, “leaving many innovators stuck in the financing gap,” a report published by Boston Consulting Group and sustainable fashion innovation hub Fashion for Good found in January.

According to the report, a handful of companies like Patagonia and H&M group have created their own venture funds, but the industry will need investments of $20 billion to $30 billion each year simply to reduce its water and energy use and waste production in line with global goals over the coming decade.

Make it Political

Politics is something the fashion industry has historically tried to avoid. But the industry’s shift to a more values-based approach to marketing has made that increasingly difficult.

Any real change will require much greater engagement with governments because brands cannot achieve their goals to operate more responsibly without systemic shifts. However well-meaning, no individual brand can ensure workers in its supply chain are getting a fair wage if all its competitors continue to undercut it. Similarly, reducing emissions across manufacturers will require a wholesale shift to cleaner energy that will likely need government support to facilitate.

Collective action “will really become crucial, because this kind of challenge we won’t be able to solve alone or company by company,” said Kering’s Daveu.

Collaboration is a relatively new concept for the intensely competitive fashion industry, but it is gradually gaining traction. Over the last few years, initiatives like the UN Fashion Industry Charter for Climate Action and the Fashion Pact have drawn in dozens of brands to collaborate on efforts to reduce the industry's environmental impact. While both groups' plans remain somewhat hazy, they provide the industry with a platform to engage with governments.

The fashion industry is facing a reckoning.

The Fashion Charter has established a working group to lobby manufacturing hubs like Vietnam and Bangladesh to incentivise the provision of renewable energy. Industry groups including the Global Fashion Agenda, the Sustainable Apparel Coalition and the Federation of the European Sporting Goods Industry joined forces last year to push forward policies that will encourage the industry to become less extractive and wasteful.

Meanwhile the crisis caused by Covid-19 has created an opportunity to bring together stakeholders to address some of fashion's social issues. Trade union groups have worked with the UN's International Labour Organisation to issue a call to action for the industry to protect workers from the immediate fallout from the pandemic and establish sustainable systems of social protection for the long-term. Brands including Calvin Klein-owner PVH, Adidas and H&M group have endorsed the move and a working group has been established to push action forward.

To be sure, government intervention is not a panacea. Regulation can be ineffective and act as an expensive hurdle for businesses that diverts funds into compliance and away from addressing the behaviours that need to be fixed. Globally, enforcement is often poor, with allegations of sweatshop conditions plaguing manufacturing in countries like the US and UK, despite the countries’ labour laws.

And yet, more intervention seems inevitable in the wake of the current crisis, as governments look to stave off future disasters and the industries that receive state support now face closer scrutiny.

Break the System

In many ways, fashion’s current business model is incompatible with operating responsibly. It relies on cheap manufacturing and high-volume, high-growth consumption for profit, both of which sit uncomfortably with environmental and social goals.

Companies that want to operate responsibly need to embrace new business models and abandon established systems.

For instance, resale is booming. In April, European luxury resale site Vestiaire Collective raised €59 million ($65 million) in a funding round that valued the company 50 percent higher than in June last year. The company and its peers look set to benefit from the glut of inventory caused by Covid-19.

E-commerce platform Zalando's co-CEO David Schneider said now is the time to double down on such initiatives. "Sustainability will remain very much a focus point for customers," Schneider said. "We definitely do not want to slow down, and you might see some things accelerate, for instance efforts around circularity, taking back used clothes and selling second hand, which might be more interesting if we enter a recession."

Meanwhile, the inventory glut created by Covid-19 is adding fresh momentum to conversations around new recycling technologies and localised and customisable manufacturing.

“Legacy systems at breaking point for the last few years, they’re gone. You won’t be able to run a business like this anymore,” said Lawrence Lenihan, chairman and co-founder of Resonance, a group of companies focused on transforming the fashion industry with on-demand-manufacturing technology. “They will burn to the ground and out of that will come some amazing new ideas.”

Progress, Not Perfection

The fashion industry is facing a reckoning. Industry watchers have complained of a broken system for years, but Covid-19 has irrevocably exposed the long-standing weaknesses in the sector’s standard business model.

There is no quick fix and no perfect solution. Many may be tempted to return to business as usual in pursuit of a near-term recovery. But the world is changing and smart companies will change with it. Brands that start to factor environmental and social considerations into their business strategies now will likely be better-placed to weather future crises and adapt to new regulations and innovations. But they should not expect it to be easy.

“Sustainability is a marathon and not a sprint,” said Seidel. “Are we acting fast enough? We could always act faster, but we’re trying to move the whole industry, and it’s a big tangle that we’re trying to move.”

BoF Professional Special Edition: Can Fashion Clean Up Its Act?

As the world grapples with an unprecedented public health and economic crisis, exposing deep-rooted social inequality as a climate emergency looms, the fashion industry must learn to respect both people and the planet. It's time for fashion to build a more responsible business model. Explore the full special edition here.

1. Can Fashion Clean Up Its Act?

2. Will Fashion Ever Be Good for the World? Its Future May Depend on It

3. How to Avoid the Greenwashing Trap

4. Luxury Brands Have a 'Respect Deficit' with Indian Artisans

5. Investing in the Sustainability Sisterhood

6. Why Luxury Came to the Rescue

7. The BoF Podcast | Jochen Zeitz on the Power of Fashion to Drive Sustainable Change

and more.

The BoF Professional Summit: How To Build a Responsible Fashion Business

On June 17 2020, we will gather leading global experts, entrepreneurs and activists in sustainability, ethical supply chains and workers' rights for a half-day programme of interactive conversations, panel discussions and workshops on building a responsible business, led by BoF's expert editors and correspondents. Space is limited. Register now to reserve your spot.

Fashion’s biggest sustainable cotton certifier said it found no evidence of non-compliance at farms covered by its standard, but acknowledged weaknesses in its monitoring approach.

As they move to protect their intellectual property, big brands are coming into conflict with a growing class of up-and-coming designers working with refashioned designer gear.

The industry needs to ditch its reliance on fossil-fuel-based materials like polyester in order to meet climate targets, according to a new report from Textile Exchange.

Cotton linked to environmental and human rights abuses in Brazil is leaking into the supply chains of major fashion brands, a new investigation has found, prompting Zara-owner Inditex to send a scathing rebuke to the industry’s biggest sustainable cotton certifier.