The Business of Fashion

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

PARIS, France — In recent years, French luxury conglomerate Kering has grown its sales, profits and market capitalisation on the back of tremendous successes at Gucci, Saint Laurent and small but fast-growing Balenciaga, which is set to surpass €1 billion ($1.1 billion) in sales this year, according to the firm.

The group has also sharpened its focus, spinning off Puma, selling off Volcom and parting ways with small-to-medium-sized brands Sergio Rossi, Christopher Kane and Stella McCartney.

In order to maintain momentum, Kering must continue to scale Gucci, Saint Laurent and Balenciaga, while developing Alexander McQueen, which remains sub-scale. The same is true for turning things around at Bottega Veneta, which generated €1.1 billion ($1.2 billion) in 2018 but has stalled after nearly two decades of expansion.

It’s also in the midst of revamping Place Vendôme jeweller Boucheron and stabilising Italian menswear label Brioni, which has struggled after years of unrest on the creative side.

ADVERTISEMENT

None of this will be easy to implement.

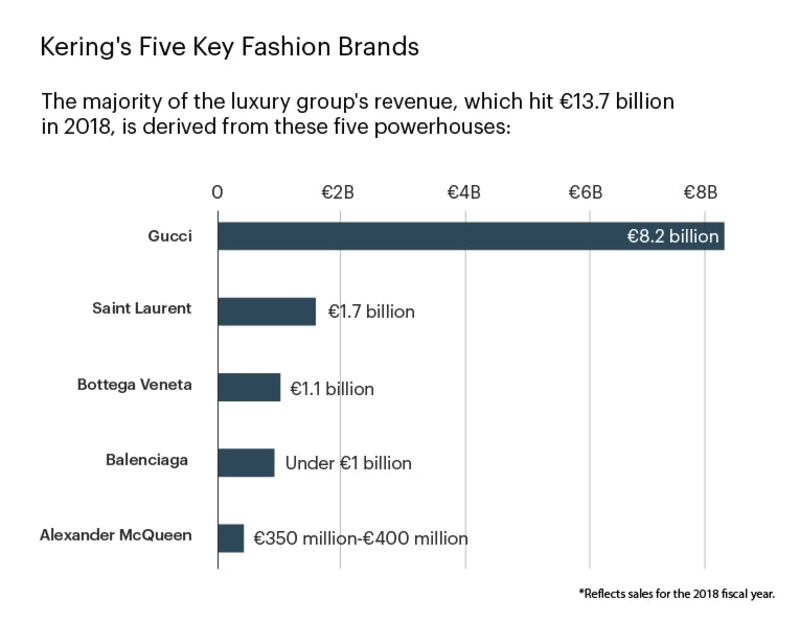

Kering's Five Key Fashion Brands | Source: BoF

In 2018, Kering generated €13.7 billion ($15.3 billion) in sales, up 26 percent from a year earlier. But much of the group's success depends on Gucci, which made up more than 60 percent of sales on the back of a disruptive creative strategy put in place by Chief Executive Marco Bizzarri and Creative Director Alessandro Michele. While Gucci continues to grow at double digits — first quarter 2019 reported sales were €2.3 billion ($2.6 billion), up 20 percent from a year earlier — growth has slowed significantly compared to the first quarter of 2018, when the Italian fashion house reported an astonishing 49 percent increase.

At Saint Laurent, where Anthony Vaccarello has largely fallen in line with the aesthetic template put in place by former Creative Director Hedi Slimane, the brand must now contend with the ascent of Slimane's Celine. McQueen lacks a strong accessories business and needs to work on further developing its brand signatures into bags and shoes that inspire repeat purchasing.

Balenciaga will face the inevitable decline of the dad-sneakers trend, which has contributed heavily to its growth under creative lead Demna Gvasalia. Plus, the turnarounds at Bottega Veneta, Boucheron and Brioni will undoubtedly take time.

To continue to create shareholder value, Kering may need to use its considerable spending power — €13 to 18 billion ($20.2 billion), according to analyst estimates based on 2018 EBITDA of €4.4 billion ($4.9 billion) — to make at least one major acquisition, if not more.

“The sector has never been so cash-rich in its entire history,” said MainFirst analyst John Guy. “Kering, specifically, has made it clear that they’re not going to sit and wait for the market to consolidate itself; they will participate in some form of M&A.”

Kering has made it clear that they're not going to sit and wait for the market to consolidate itself.

On a February 2019 call with investors, Kering Chief Executive François-Henri Pinault underscored this. "On M&A, we have significant financial resources that are increasing steadily. So, we're in a position to seize opportunities," he said, noting, however, that growing sales at the group's current brands — including cash cow Gucci — remains the top priority.

ADVERTISEMENT

“We don’t need M&A to grow. Far from it,” he added. “You've seen three years of very strong growth without M&A. We have the means. We have the platforms. If the opportunities meet the portfolio criteria, we'll be able to seize them at a realistic price. We're not going to engage in a price race. We've never done so before.”

But any deal Kering does will be scrutinised by the market.

“Investors are weary when Kering talks about acquisitions,” Guy said. “They’ve always overpaid and haven’t been able to generate decent returns. Their track record in disposals, on the other hand, has been excellent. And they’ve got brands within their soft luxury portfolio that they can develop more.”

Organic growth may well be top of mind, but “the group will remain opportunistic when it comes to acquisitions, as long as they meet certain criteria,” Citigroup analyst Thomas Chauvet wrote in a recent note.

Any acquisition would need to be transformational in terms of scale, not least because Kering is "overdependent" on Gucci and has had difficulty in the past integrating mid-sized brands, added Chauvet. It would also need to complement Kering's existing portfolio in terms of both business model and aesthetic, easily plug into its supply chain and logistics platform, and offer a major growth opportunity in China, which is set to become the world's largest fashion market this year, according to BoF and McKinsey's State of Fashion 2019 report. The target must also be bought for a fair valuation, without the need to do a major reorganisation or brand transformation, Chauvet said.

Companies that possess all of these qualities are rare, however.

Kering considered buying Versace, according to a source familiar with the negotiations, but decided in the end that the Italian house and its investors, private equity firm Blackstone, were asking for too high a price. (Kering did not respond to a request for comment regarding this.) Some sort of partnership with Chanel — probably a merger — is a white-whale scenario.

A partnership with Swiss luxury group Richemont, which has the hard luxury expertise Kering lacks and could, in turn, use Kering's fashion know-how to support Chloé, may be something the market would welcome, but it's equally unlikely because of the uncertainty around how to manage the balance of power between Pinault and Richemont chairman Johann Rupert.

ADVERTISEMENT

Italian leather goods maker Tod's could be interesting, but owner Diego Della Valle's close relationship with LVMH — where he serves on the board of directors — means that if he were to sell, it would likely be to Bernard Arnault.

Armani, too, is attractive in that it is a global brand. But it has never been strong in margin-driving accessories and founder Giorgio Armani has stated many times that he has no plans to sell the company, even setting up a charitable trust that will make it difficult for an outside entity to buy it in the future.

There are, however, a handful of compelling prospects that tick most, if not all, of Kering’s boxes.

VALENTINO

Valentino Autumn/Winter 2019 | Source: InDigital.Tv

Mayhoola for Investments, the fund backed by the Qatari royal family, acquired the Italian house in 2012 for $850 million, signaling that it might be readying itself to build a luxury group of its own. That idea was reinforced in 2016 when it bought Balmain in a deal that valued the brand at close to €500 million ($559.8 million), or 14 times its EBITDA.

Late last year, however, rumours circulated that the group might be interested in selling Valentino, where 2018 sales were €1.2 billion ($1.34 billion), up 3 percent from €1.16 billion ($1.3 billion) a year earlier, noting Kering as a potential suitor. Kering declined to comment, as did Mayhoola and Valentino.

But sources familiar with the thinking of each party said that this was purely market speculation, and vehemently denied that any such talks occurred. According to a person familiar with Mayhoola business, the company is still very much engaged and is playing the "long game" in terms of acquisitions. The person said that Mayhoola's disposal of its stake in British handbag label Anya Hindmarch had nothing to do with its overall ambitions.

However, this has not stopped the market from wishing a deal with Kering for Valentino was in the works.

Pros: Valentino is a globally recognised brand with a strong heritage, a robust accessories business and, in Pierpaolo Piccioli, a creative director whose runway collections, both ready-to-wear and couture, are a favourite of critics, as well as celebrity stylists and other designers, who heavily reference his work.

Piccioli’s vision stands apart from that of other brands in the Kering portfolio, lowering the risk of cannibalisation. Valentino would also benefit from Kering’s established infrastructure: access to more suppliers, a bigger retail network and a wider range of executive talent could help accelerate the brand’s growth. In December 2018, the brand partnered with Alibaba to drive sales in China.

Cons: The label's growth has slowed in recent years, as the accessories offering is still reliant on past hits including the "Tango" ankle-strap pump, "Open" white sneakers and the "Rockstud" range. A deal would also certainly be contingent on Piccioli's commitment to remaining with the brand for multiple years. That said, while Valentino remains the strongest target for Kering, it would come at a significant price given Mayhoola's commitment.

MONCLER

Moncler Genius Autumn/Winter 2019 | Source: InDigital.Tv

The Italian luxury outerwear label is growing rapidly, generating €1.42 billion ($1.59 billion) in sales in 2018, up 22 percent from a year earlier. Some of that success has to do with a pivot in business model, moving away from seasonal collections in favour of quick-hit, Instagram-friendly capsule collections designed in collaboration with top creatives. Dubbed "Moncler Genius," the project has been good for both brand awareness and attracting new customers. In 2018, about half of the customers who visited Moncler boutiques to shop the Genius collections were new to the brand.

Pros: Moncler is complementary to Kering on a lot of levels. Kering could apply some of the lessons learned from Moncler's drops-driven approach to its other brands. At the same time, Moncler's core competency, puffer jackets, is unlike anything else Kering offers and has an evergreen, utilitarian quality that makes it a safer bet. Its global brand awareness, especially in important markets like China, is another plus. And yet, it's not overpenetrated and there is room to further expand into categories beyond outerwear. Here, Moncler would benefit from Kering's expertise.

Cons: Chief Executive Remo Ruffini, who has ushered the brand through several sales and an initial public offering, might not be motivated to sell at the moment, given that he still owns 26 percent of a business that continues to grow at double-digit rates.

"It would seem to me a shame to be selling now," he told Reuters in April, also mentioning that he would like to see how the brand develops over the next three to four years. Ruffini is also used to running Moncler independently, without the input from another layer of senior executives.

TIFFANY & CO.

Tiffany & Co store in Hong Kong | Source: Shutterstock

One of just a few independent jewellery houses remaining, Tiffany & Co. has long been viewed as a takeover target by analysts that think the US company’s board has sometimes been too conservative in brand development. With a market capitalisation of around $13 billion, it’s also expensive. But Tiffany, which generated $4.4 billion in its 2018 fiscal year, is also rare enough in its global appeal and recognition to make it a compelling prospect.

Pros: Tiffany has the scale Kering is looking for, in the category where it does not yet own a dominant player. (Boucheron, its biggest jewellery brand, remains small and is currently undergoing a revamp.) Tiffany also has a healthy business that is growing quickly in Asia, which represented 28 percent of sales in 2018, up 13 percent from a year earlier. What's more, Italian Chief Executive Alessandro Bogliolo, who spent many years at LVMH-owned Bulgari and Sephora, as well as Diesel, understands the European side of the luxury sector.

Cons: Tiffany's high-low positioning — it sells six-figure fine jewellery pieces, but also $60 silver chains — means that it is not always viewed by the consumer as pure luxury. And Kering has made it clear that it does not want to veer too far away from that core competency in luxury.

“Tiffany is not a Cartier,” Guy said. “It’s a Jekyll-and-Hyde brand; two brands in one. Some investors struggle with that positioning.” Plus, Tiffany is also still learning to navigate a market being reshaped by jewellery customers who are less bound to tradition (and diamond engagement rings) than before. And while Tiffany has a lot of room to grow in China, it must also compete with fine jewellery collections from world-renowned fashion houses, direct-to-consumer brands and increasingly popular, designer-driven niche lines.

Many analysts believe that LVMH is more likely to buy Tiffany, which the company has said in the past that it wishes to remain independent. Not only does it have more spending power, but its network of 70 brands is more varied in price point and target customer.

CHLOÉ

Chloé C bag | Source: Shutterstock

While the female-founded Parisian fashion house is owned by Kering rival Richemont, investors and analysts have long wondered whether the Swiss luxury group should sell off its soft luxury interests, which are outside its core competency and have been slower to scale than its watch and jewellery assets. While Richemont doesn't break out sales figures for Chloé, sales in its "other" category — which include Chloé, Alaïa and Dunhill — were about €1.8 billion ($2 billion), approximately €500 million ($559.8 million) of which was generated by Chloé, according to analyst estimates.

Pros: Chloé is a globally recognised brand with a DNA rooted in femininity and female creativity. It also has an aesthetic that complements but doesn't directly compete with Gucci and Saint Laurent. What's more, the brand's 1970s bourgeoisie spirit can be adapted easily to current trends and is less reliant on a single creative director's vision to carry it out. (Since Stella McCartney joined the label in the late 1990s, it has been driven by strong female designers, including Phoebe Philo, Clare Waight Keller and now, Natacha Ramsay-Levi.) It's also strong in both shoes and handbags, margin-driving categories with styles that carry over from season to season.

Cons: Kering already has several brands around Chloé's size that it still needs to scale up, which requires additional investment. And it's unlikely that Richemont, which has struggled in the fashion space, will relinquish Chloé, given that it is its most successful soft-luxury brand.

SALVATORE FERRAGAMO

Salvatore Ferragamo Vara Lux Flap bag | Source: Shutterstock

For years, Salvatore Ferragamo was pegged as a "sleeping beauty" brand, with the right DNA but bogged down by multiple executive changeovers and a family-dominated ownership structure. The company has a sizable retail foothold in both China and the US but has long failed to innovate on product and brand image.

Now, the label is now showing new signs of life. The elevation of designer Paul Andrew in February 2019 has been well received. Analysts expect sales for the first quarter of 2019 to improve, driven in part by Andrew's new styles, including the top-selling "Studio" bag and "Flower" heels. Sales were €1.4 billion ($1.6 billion) in 2018.

Pros: An incredibly strong brand with plenty of room to grow, Salvatore Ferragamo could be quickly revived by Kering, where executives and designers are given an established framework and then free reign to work within that structure. It also seems that, with the passing of matriarch Wanda Ferragamo in October 2018, that some members of the family, which owns the majority of the business through a holding company, would be more willing to sell.

Cons: One important family member has quashed this speculation, however.

"I'm in love with this company and it's not for sale," chairman Ferruccio Ferragamo told Bloomberg in February. "There's a lot of energy in the brand. We have a lot of programs coming to turn that energy into good news in the coming weeks and months."Ferragamo also is already heavily penetrated in China, which means growth will need to come from more than regional expansion.

BURBERRY

Burberry Autumn/Winter 2019 | Source: InDigital.Tv

The UK label, which underwent a major, innovation-led transformation in the 2000s under the watch of Christopher Bailey and Angela Ahrendts, has long been the subject of takeover speculation, with US-based Tapestry, Inc, which owns Coach, often named as a possible acquirer. Now, Burberry is in the midst of another turnaround, led by Chief Executive Marco Gobbetti and creative director Riccardo Tisci, who are trying to clarify the brand's positioning, which has hovered below the true luxury level. Sales in 2018 were £2.7 billion ($3.5 billion), up 2 percent from a year earlier, with half-year sales for 2019 up 4 percent.

Pros: While Tisci's effect on the house hasn't set off fireworks, it has managed to begin to shift consumer perception as its positioning moves further upmarket. By September 2019, more than half of the product on the market will be "Riccardo" product, distributed in novel ways, including drops and collaborations.

The brand’s social media savvy — an important element for Kering — continues to set it apart, with social conversation reaching around 57 million consumers in 2018, according to a report from the company. The duo of Gobbetti and Tisci also lines up with the Kering approach, which is to match a strong executive with an equally strong creative so that they can form a long-lasting partnership. Its heritage helps maintain a baseline reputation for quality even during more difficult fashion cycles.

Cons: While Gobbetti may be successful longterm in moving Burberry further upmarket, it still has a way to go. (The company is currently in the first stage of a two-stage strategy: the first two years are about investing in brand positioning; the second is about tweaking distribution and investing experience.) The brand is also already quite heavily distributed in Asia, which makes up over 40 percent of the business, so there is less opportunity for rapid growth there.

CHOPARD

Chopard store in Prague | Source: Shutterstock

With more than $900 million in sales and a history going all the way back to 1860, the Swiss jewellery and watch brand, recognised for its diamond-encrusted timepieces, remains a highly desirable target for the leading luxury groups. (It’s owned by the Scheufele family, which bought it in 1963 when there were only five people employed by the business.)

Pros: It's a pristine name that could help cement Kering's standing in hard luxury. "The jewellery market is buoyant," Pinault has said.

Cons: The family has shown little interest in selling, according to market sources.

PATEK PHILIPPE

Patek Philippe | Source: Shutterstock

Another hard luxury player with plenty of appeal, Swiss watch brand Patek Philippe generates more than €1 billion ($1.1 billion) a year in sales and is a perennial favourite with watch collectors.

Pros: If Kering, which currently owns Ulysse Nardin and Girard-Perregaux, were to buy Patek, it would further underscore its commitment to developing its watch business, a major cash generator for Richemont.

Cons: The Stern family, which has owned Patek for four generations, said in 2019 that the company is not for sale, despite the fact the it would likely be valued at €7 billion to €9 billion ($10.1 billion) in an acquisition. Plus, the future of the Swiss watch market, which is beginning to stagnate, is in question. "For the time being, we're observing," Pinault said in February, noting that the company already has two watch brands, Ulysse Nardin and Girard-Perregaux.

Related Articles:

The Swiss watch sector’s slide appears to be more pronounced than the wider luxury slowdown, but industry insiders and analysts urge perspective.

The LVMH-linked firm is betting its $545 million stake in the Italian shoemaker will yield the double-digit returns private equity typically seeks.

The Coach owner’s results will provide another opportunity to stick up for its acquisition of rival Capri. And the Met Gala will do its best to ignore the TikTok ban and labour strife at Conde Nast.

The former CFDA president sat down with BoF founder and editor-in-chief Imran Amed to discuss his remarkable life and career and how big business has changed the fashion industry.