The Business of Fashion

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

When Kering announced the creation of its eyewear division in 2014, the consensus view was that this was a risky move, almost a step too far. Kering’s eyewear division is now targeting annual revenues of over $2 billion, with much of that coming from licences that have lapsed with Italian eyewear manufacturer Safilo, leaving Safilo’s valuation in the doldrums. (To make matters worse for Safilo, LVMH which had initially set up a joint venture with the company, eventually set up its own eyewear division, Thélios, in partnership with Safilo’s rival Marcolin, resulting in the loss of further licences for the struggling eyewear group).

Now, Kering has hired former Estée Lauder executive Raffaella Cornaggia to lead a new beauty division, which is set to develop the beauty category for several of its brands, including Bottega Veneta, Balenciaga and Alexander McQueen, echoing the formation of its eyewear division in 2014. Why? And what are the implications of the move, particularly as two of Kering’s top brands are still under licence to beauty giants Coty and L’Oréal?

It is no secret that Kering lost out to Estée Lauder in the bidding process for Tom Ford. Tom Ford Beauty has long been the main driver of sales and profits of the brand and Estée Lauder couldn’t afford to lose the licence but, more importantly, knows how to grow that side of the business. Kering was effectively gazumped but was right not to fight to the bitter end.

It was a big move from a beauty group, though not the first one. Most famously, Chanel is owned by its former beauty partner (dating back to the 1920s), but other beauty groups have made moves similar to Estée Lauder’s to protect a beauty cash cow: Clarins acquired Mugler’s fashion business in 1997 on the back of the huge success of Angel, the brand’s flagship fragrance it had created as a licensee. (Both the fragrance business and the fashion line were later sold by Clarins to L’Oréal).

ADVERTISEMENT

Puig has been following the same playbook for a while, acquiring Nina Ricci, Carolina Herrera, Paco Rabanne and taking a majority stake in Jean Paul Gaultier in 2011 before acquiring the licence to the brand’s fragrances from Shiseido in 2016. What makes the Tom Ford acquisition so unique is its size and notoriety.

Scale may also be a factor in the timing of Kering’s move into beauty. Whilst Gucci and Yves Saint Laurent are still licensed to Coty and L’Oréal respectively, Kering can get to work on smaller brands Bottega Veneta, Balenciaga and Alexander McQueen.

And yet many smaller brands have fallen on their swords by going into beauty independently. Burberry terminated its beauty licence with Interparfums in 2012, taking the operations in house, only to award a licence to Coty in 2017. Prada first entered the beauty category in 2000 on its own terms, eschewing fragrances in favour of skincare and makeup in three main divisions: “multidose” items, mainly for basic skin care; “monodose” products, for specific treatments; and “minidose” units for colour. The launch proved too complicated and was eventually discontinued in favour of a 50/50 joint venture with Puig centred solely on fragrances. In 2019, the brand signed a deal with L’Oréal, effective January 2021, to develop and sell luxury beauty under the Prada brand name.

Kering may be hedging its bets by starting off with its smaller brands but, in the long term, the more valuable Yves Saint Laurent and Gucci beauty lines, still under licence with others, will surely come into focus.

What does this mean for beauty groups relying on licensed brands?

Coty seems particularly vulnerable as its business model is centred on licensing (its biggest licence being Gucci), although the group’s size and diversified portfolio offers a degree of protection. It is also the go-to licensee for brands not willing to operate their own beauty business. Whilst the group’s stock price did not move much upon Kering’s announcement (in fact, Coty’s share price has increased by 9 percent since), Safilo’s struggles must serve as a cautionary tale.

Alternative licensing players such as Interparfums and (on a much smaller scale) Euroitalia have been careful to enter into long-term licences and sought to acquire the rights to some of their brands in the category (such Lanvin which is owned by Interparfums in trademark class 3).

Other participants in beauty licensing have less exposure to this risk: L’Oréal and Estée Lauder have sufficient clout with their owned brands to weather any potential disruption caused by beauty licences being brought in house by their owners. Puig has also diversified risk, not only by buying fashion brands, but also by making significant acquisitions in the beauty sector, such as Charlotte Tilbury and Byredo.

ADVERTISEMENT

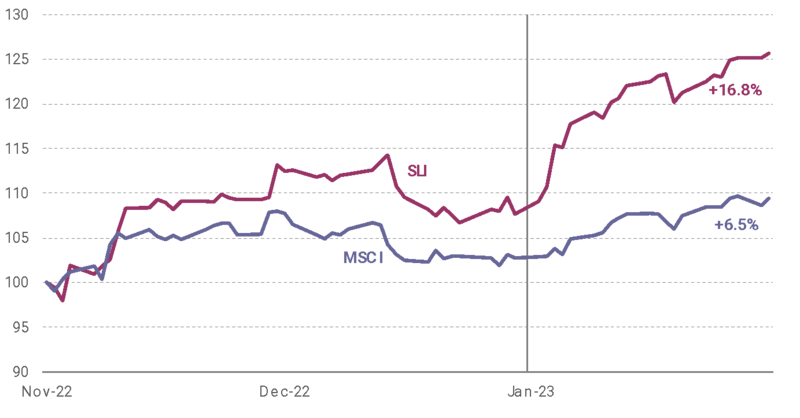

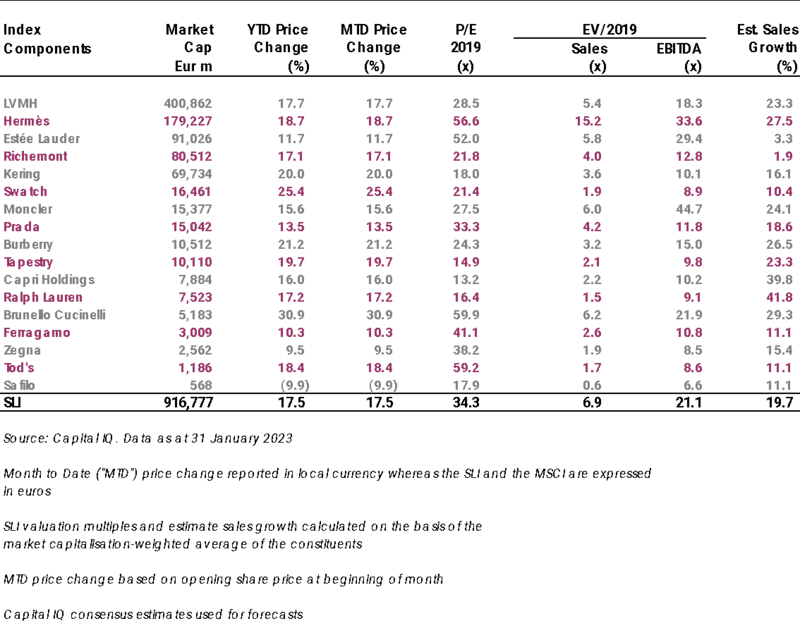

The Savigny Luxury Index (“SLI”) rose 16.8 percent in January, outperforming the MSCI by over 10 percentage points, driven by a string of positive results announcements for 2022 and refuelled optimism over the unlocking of China after ‘zero Covid.’

Going up

Going down

What to watch

Kering’s latest move indicates that the battle lines between fashion-accessories and beauty players are being drawn up. This could make up for an interesting year in the mergers and acquisition space for both fashion and beauty.

Pierre Mallevays is a partner and co-head of merchant banking at Stanhope Capital Group.

Opens in new window

Opens in new windowAccording to an email viewed by The Business of Beauty, the company will be on hiatus while it establishes a sustainable path to return as a new company.

The surfing legend, a vocal opponent of chemical-based sun protection, is launching his own line of natural skincare products this week.

While light on obvious social stunts, the 2024 Met Gala still had its share of trending beauty moments this year.

TikTok has birthed beauty trends with very little staying power. Despite this reality, labels are increasingly using sweet treats like glazed donuts, jelly and gummy bears to sell their products to Gen-Z shoppers.